-

Psathyrellaceae Vilgalys, Montecalvo & Redhead mushrooms are characterized by having a deliquescent fruiting body that has a special autodigestive phase of ontogeny on which the maturing fruiting body undergoes extensive cell autolysis that involves all the tissues of the cap and becomes a blackish inky fluid when mixed with a blackish mass of spores[1]. According to Sharp[2] and Nagy et al.[1], Psathyrellaceae mushrooms are morphologically characterized by their small to medium-sized, dark-spored, delicate fruiting bodies, which frequently have soft, delicate stems and caps. In an earlier classification, Psathyrellaceae, formerly known as Coprinaceae, are divided into two large genera: the autodigesting species of Coprinus Pers. and the non-autodigesting species of Psathyrella, respectively[1]. These mushrooms are widely distributed in both tropical and temperate countries, which thrive in different types of substrates such as soils, leaf litter, dead branches, and ruminant dung, among others[3−20].

The Coprinellus mushrooms, one of the genera belonging to Psathyrellaceae, were derived from Coprinus (Pseudocoprinus Kühner), and were introduced to accommodate partially deliquescent species (such as Coprinellus disseminatus) and are now recognized as one of the established genera of Psathyrellaceae with over 71 species recorded based on the mycological data of the Species Fungorum[21]. In terms of its morphology, Coprinellus species are divided into three large clades, the Setulusi, Micacei, and Domestici clades, based on the existence of cap pileocystidia and the morphology of its veil[13,22]. Although these groupings tend to reflect morphological characteristics, molecular studies have demonstrated some phylogenetic inconsistencies, particularly in the distribution of setulose within clades[23]. In addition, Coprinellus is one of the coprinoid or inky caps fungi that exhibit distinctive features, including the dark pigmented basidiospores, occurrence of pseudoparaphyses in the hymenium, deliquescent lamellae, and sequential basidial development[24]. Similar to all other coprinoid genera, Coprinellus species can be distinguished from typical agarics by their gills, which liquefy as the mushroom matures[22]. Moreover, Coprinellus immature gills are not pinkish, with either present or absent veil, deliquescent or non-deliquescent cap during sporulation, and the pileipellis consists of hymeniderm or cystoderm of globose to piriform cells[25]. Ecologically, Coprinellus is characterized as a saprophytic fungus that grows in nutrient-rich substrates, including dead trees, branches, leaf litter, grassy debris, bare soil, and ruminant dung[26].

Furthermore, various studies have already classified taxonomically the different species of Coprinellus, particularly the newly recorded species from diverse countries. In the study of Gomes & Wartchow[27], they reported the taxonomy of the new species Coprinellus arenicola isolated from Paraíba, Brazil, based on its holotype, basidiomata, pileus, lamellae, stipe, basal mycelium, basidiospores, basidia, cheilocystidia, pileipellis, stipitipellis, elements of veil on pileus, etymology, habitat, and distribution. Accordingly, C. arenicola is a newly described species of small, subgregarious basidiomycete fungi characterized by a buff to pale beige, plicate-pectinate pileus, adnexed grayish to black lamellae, a smooth, white, hollow stipe, an absent annulus, heart-shaped to triangular basidiospores, and habitat specificity to sandy soils in Paraíba, Brazil. Similarly, Coprinellus ovatus from Pakistan is characterized as a small, caespitose fungus with an orange-yellow, fibrillose, plicate pileus, free brownish-black lamellae, a yellowish-brown radicating stipe, mitriform to amygdaliform basidiospores, utriform cheilocystidia, and grows among broadleaf trees[22]. Overall, different species of Coprinellus share similar features such as deliquescent lamellae, small basidiomata, and saprophytic nutrition since they all belong to the same family, Psathyrellaceae, but can be morphologically distinguished from one another based on the differences in color of the lamella, stipe, structure of basidiospore, presence or absence of cheilocystidia, color, and structure of pileus, among others.

Furthermore, Coprinellus mushrooms are widely documented and studied, with Europe being among the top continents with the most Coprinellus mushrooms recorded[6,8,13,16,18,23,24,28−49]. Aside from species identification, the different bioactivities of the genus Coprinellus have also been elucidated, including antifungal[50], anticholinesterase[51], and antioxidant[46] activities. Moreover, the co-culturing of C. radians and C. disseminatus stimulates seed germination in Cremastra appendiculata[52,53].

In addition to their bioactivities, novel bioactive compounds were also screened in Coprinellus mushrooms. For instance, Tešanović et al.[46] extracted different phenolic compounds such as flavones, flavonols, flavanones, flavanols, bioflavonoids, isoflavonoids, hydroxybenzoic acids, hydroxycinnamic acids, coumarins, cyclohexanecarboxylic acids, and chlorogenic acids in the hot water extract of C. truncorum. Meanwhile, in the qualitative analysis of the fatty acid composition of Coprinellus curtus, C. disseminatus, C. domesticus, Coprinellus ellissi, C. micaceus, and C. radians mycelia, both unsaturated (linoleic and oleic) and saturated (palmitic, stearic, and myristic) fatty acids were present[29].

Given the potential of Coprinellus, this review highlights the global distribution, various bioactive compounds, and biological activities of Coprinellus mushrooms, emphasizing their importance in different industries and underscoring the gaps for future studies.

-

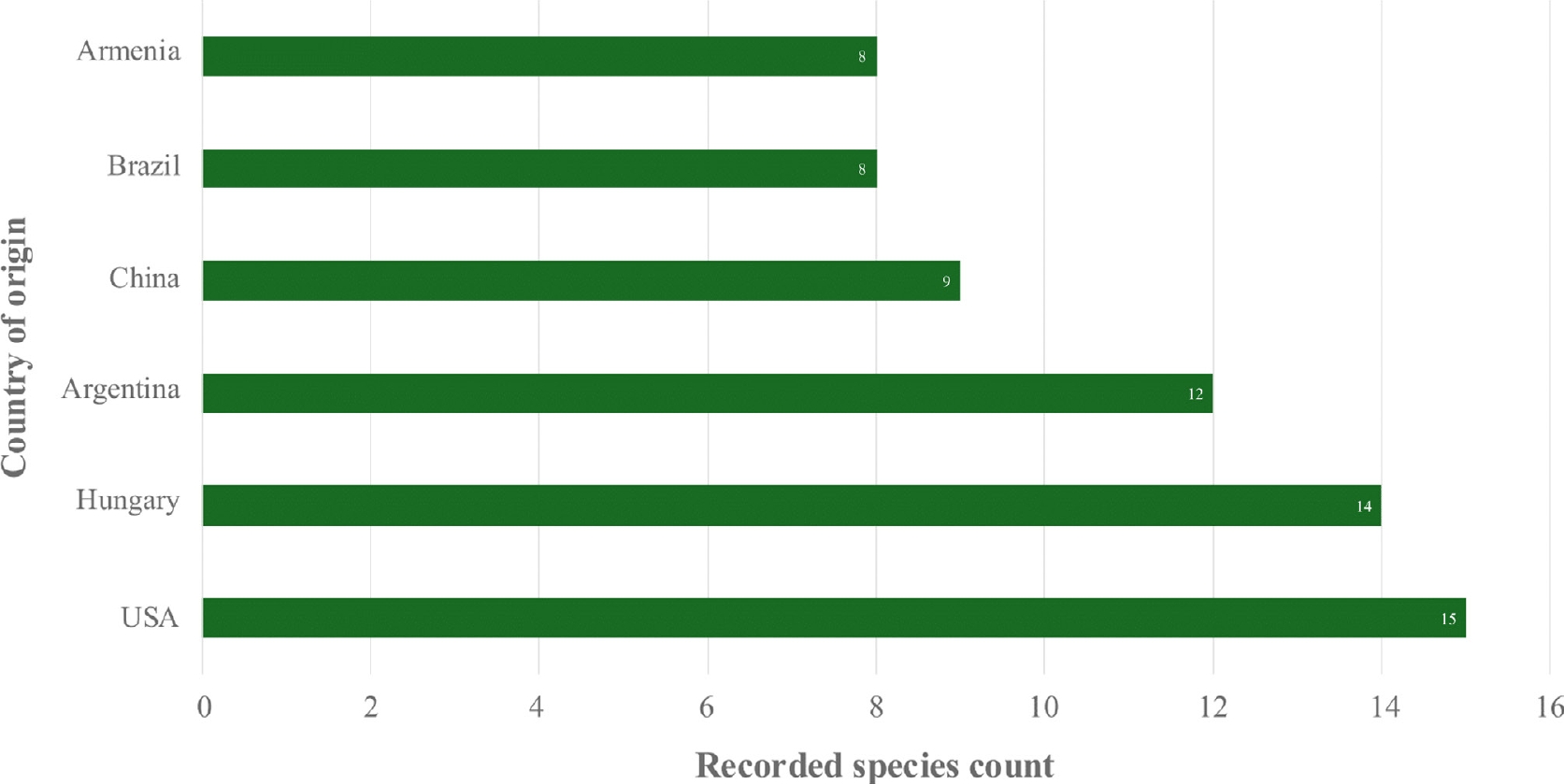

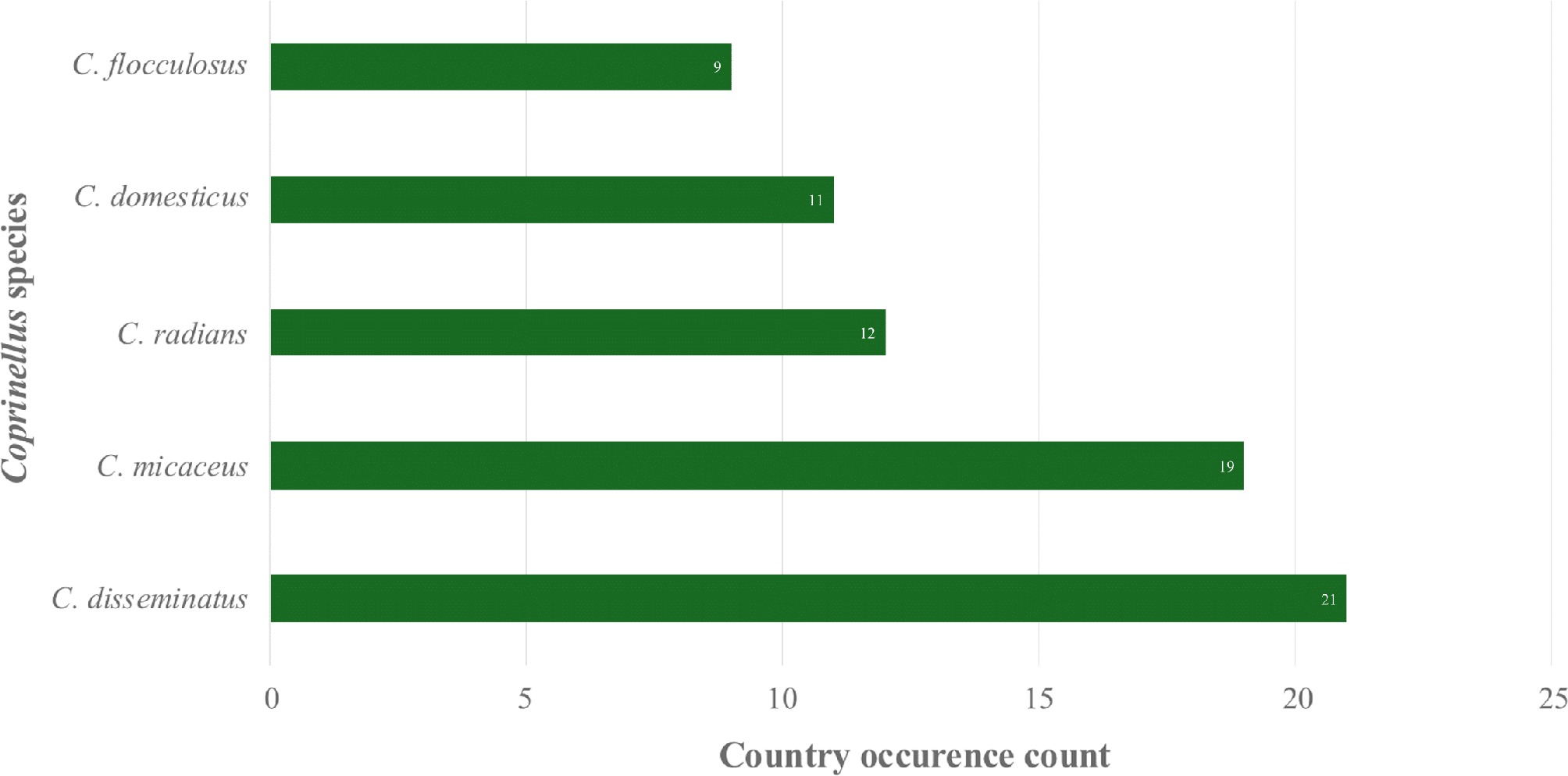

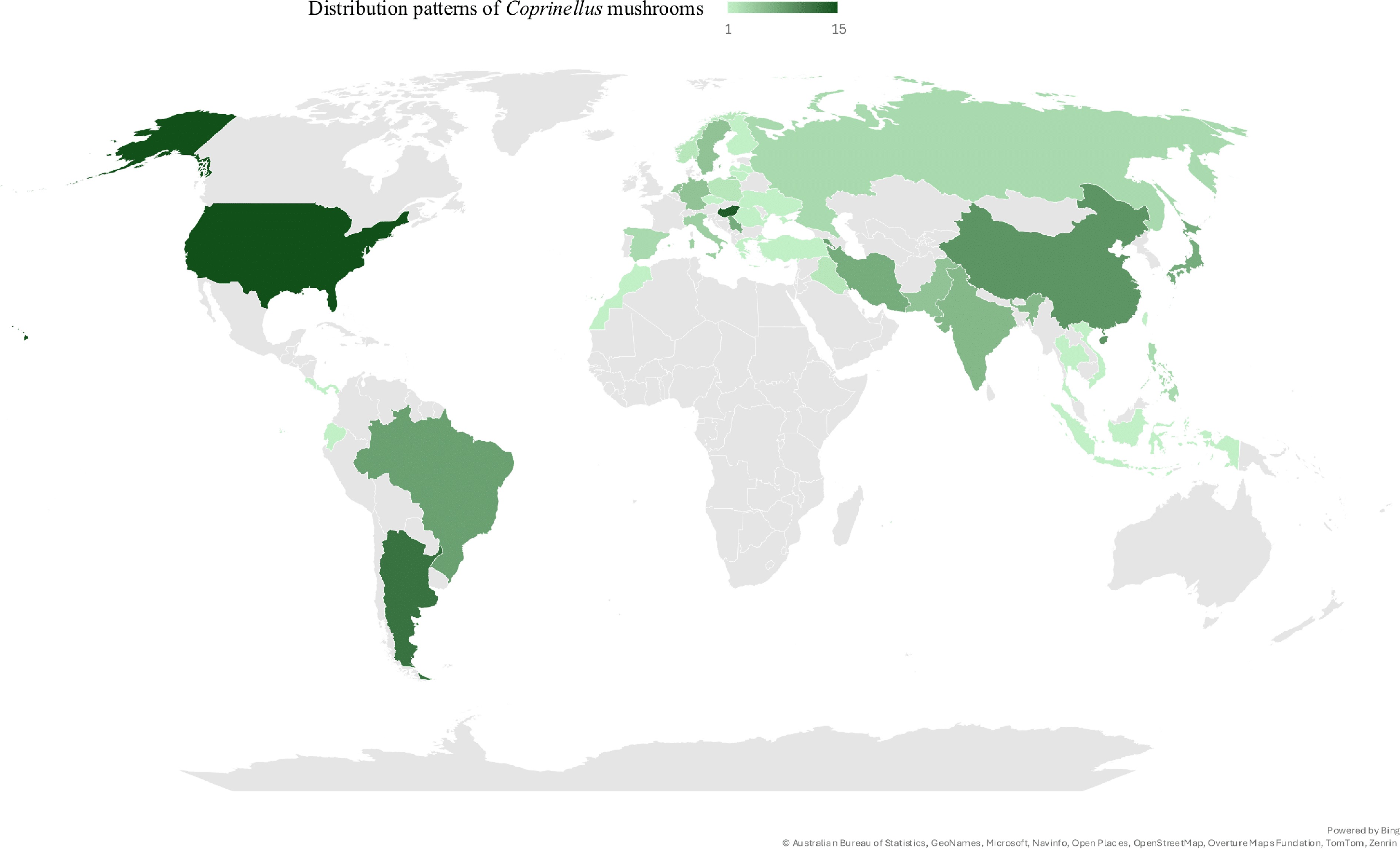

Nutritional and physical factors, including substrates, microclimates, temperature, pH, humidity, and elevation, significantly influence the distribution of mushrooms. Given this environmental sensitivity, the ability of Psathyrellaceae mushrooms to thrive across a wide range of climatic conditions is particularly notable, as evident in their global distribution records[3−20]. Moreover, Coprinellus mushrooms, belonging to the family Psathyrellaceae, also display broad thermal tolerance, as recorded in both tropical and temperate countries (Fig. 1). In the present review, a total of 67 Coprinellus mushrooms were recorded based on available reports from various studies, including species listing, diversity assessment, biological compound profiling, and bioactivity assessments (Table 1). The Coprinellus mushrooms demonstrated a wide geographical distribution, with the USA, Hungary, Argentina, China, Brazil, and Armenia representing the countries with the most recorded instances of Coprinellus mushrooms (Fig. 2). Notably, particular species of Coprinellus exhibit broad distributions, including Coprinellus disseminatus, Coprinellus micaceus, Coprinellus radians, Coprinellus domesticus, and Coprinellus flocculosus, which are among the top species of Coprinellus that are widely distributed (Fig. 3).

Figure 1.

Global occurrence patterns of Coprinellus mushrooms, visualized using filled map tools in Microsoft Excel 2019.

Table 1. Global distribution of Corpinellus species.

Coprinellus species Country of origin Ref. 1. Coprinellus alkalinus (Anastasiou) Voto (2021) n.r. [54] 2. Coprinellus alvesii Voto (2019) Brazil [55] 3. Coprinellus andreorum Sammut & Karich (2021) Malta [56] 4. Coprinellus apleurocystidiosus Voto (2021) n.r. [54] 5. Coprinellus aquatilis (Peck) Voto (2019) Finland [57] Norway [57] USA (New York) [58] 6. Coprinellus arenicola Wartchow & A.R.P. Gomes (2014) Brazil [27] 7. Coprinellus aureodisseminatus T. Bau & L.Y. Zhu (2024) China [59] Ecuador [40] 8. Coprinellus aureogranulatus (Uljé & Aptroot) Redhead, Vilgalys & Moncalvo (2001) Netherlands [32] China [12] Vietnam [60] Philippines [61] 9. Coprinellus austrodisseminatus T. Bau & L.Y. Zhu (2024) China [59] 10. Coprinellus bipellis (Romagn.) P. Roux, Guy García & Borgar. (2006) Morocco [62] 11. Coprinellus campanulatus S. Hussain & H. Ahmad (2018) Pakistan [13] 12. Coprinellus carbonicola (Singer) Voto (2020) Argentina [27] 13. Coprinellus castaneus (Berk. & Broome) Voto (2020) Mauritius [63] 14. Coprinellus chaignonii (Pat.) Voto (2019) n.r. [64] 15. Coprinellus crassitunicatus Voto (2021) n.r. [54] 16. Coprinellus criniticaulis Voto (2021) n.r. [36] 17. Coprinellus curtoides Voto (2021) USA (Hawaii) [14] 18. Coprinellus curtus (Kalchbr.) Vilgalys, Hopple & Jacq. Johnson (2001) Hungary [32] USA (North Carolina) [65] Japan [66] Armenia [29] Italy [8] Argentina [67] Sweden [13] 19. Coprinellus deliquescens (Bull.) P. Karst. (1879) India [3] Argentina [67] 20. Coprinellus deminutus (Enderle) Valade (2014) Hungary [32] 21. Coprinellus dendrocystotus (Voto) Voto (2023) n.r. [68] 22. Coprinellus dilectus (Fr.) Redhead, Vilgalys & Moncalvo (2001) Poland [9] Netherlands [35] Germany [35] 23. Coprinellus disseminatisimilis S. Hussain (2018) Pakistan [13] 24. Coprinellus disseminatus (Pers.) J.E. Lange (1938) China [69] Russia [40] Hungary [32] Lithuania [70] Latvia [71] Sweden [40] USA (North Carolina) [72] Armenia [5] Japan [73] Serbia [44] Iran [74] Indonesia [75] Iraq [20] India [76] Philippines [77] Brazil [78] Russia (Karelia) [41] USA (Hawaii) [79] Korea [79] Costa Rica [80] Argentina [67] 25. Coprinellus domesticus (Bolton) Vilgalys, Hopple & Jacq. Johnson (2001) Hungary [32] Panama [81] USA (North Carolina) [65] Iran [82] Armenia [29] West Africa (Côte d'Ivoire) [83] Spain [47] Japan [84] Serbia [45] Argentina [67] Netherlands [13] 26. Coprinellus duricystidiosus Voto (2021) n.r. [54] 27. Coprinellus ellisii (P.D. Orton) Redhead, Vilgalys & Moncalvo (2001) USA

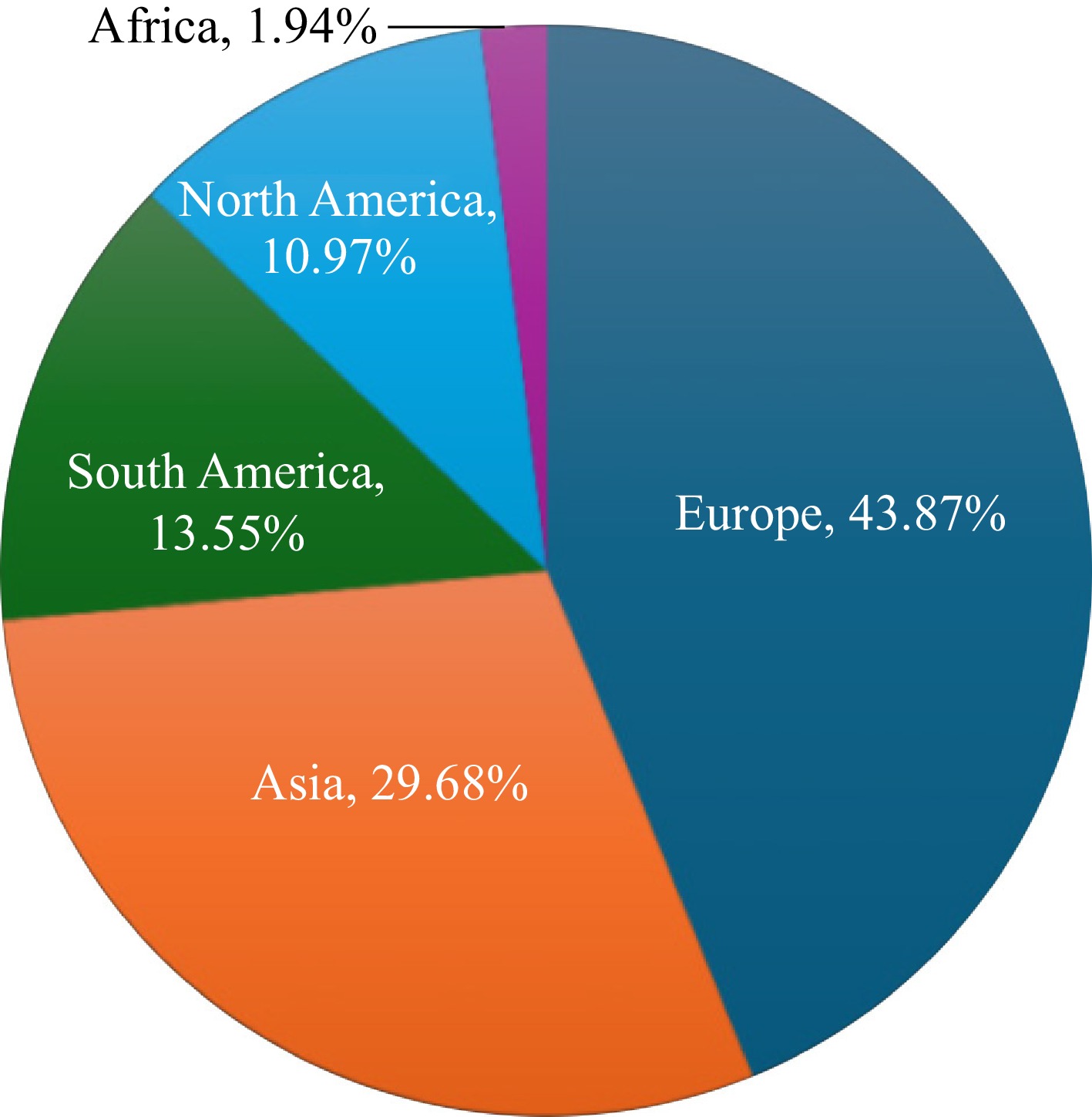

(North Carolina)[85] Japan [73] Armenia [29] 28. Coprinellus ephemerus (Bull.) Redhead, Vilgalys & Moncalvo (2001) India [3] Italy [8] Argentina [67] 29. Coprinellus fimbriatus (Berk. & Broome) Redhead, Vilgalys & Moncalvo (2001) India [3] 30. Coprinellus flocculosus (DC.) Vilgalys, Hopple & Jacq. Johnson (2001) Hungary [32] USA (North Carolina) [39] Iran [74] Iraq [20] Poland [11] Armenia [29] Italy [8] Spain [47] Norway [13] 31. Coprinellus furfurellus (Berk. & Broome) Redhead, Vilgalys & Moncalvo (2001) n.r. [21] 32. Coprinellus heptemerus (M. Lange & A.H. Sm.) Vilgalys, Hopple & Jacq. Johnson (2001) USA [86] Hungary [33] Italy [8] 33. Coprinellus limicola (Uljé) Doveri & Sarrocco (2011) n.r. [28] 34. Coprinellus magnoliae N.I. de Silva, Lumyong & K.D. Hyde (2021) Thailand [87] China [59] 35. Coprinellus maysoidisporus Voto (2021) n.r. [54] 36. Coprinellus micaceus (Bull.) Vilgalys, Hopple & Jacq. Johnson (2001) Hungary [32] China [59] Armenia [85] Japan [73] Iran [20] USA (Virginia) [88] Russia (Volograd) [43] Turkey [89] India [3] Greece [90] Japan [79] Korea [91] UK (Wales) [92] Germany [37] Romania [93] Serbia [45] Brazil [36] Argentina [67] Philippines [7] 37. Coprinellus neodilectus Voto (2019) Brazil [55] 38. Coprinellus occultivolvatus Voto (2021) n.r. [54] 39. Coprinellus ovatus M. Kamran & Jabeen (2020) Pakistan [22] 40. Coprinellus pallidissimus (Romagn.) P. Roux, Guy García & S. Roux (2006) Spain [48] 41. Coprinellus papillatus Voto (2021) n.r. [54] 42. Coprinellus parapellucidus Voto (2021) n.r. [54] 43. Coprinellus parcus T. Bau, L.Y. Zhu & M. Huang (2024) China [59] 44. Coprinellus parvulus (P.-J. Keizer & Uljé) Házi, L. Nagy, Papp & Vágvölgyi (2011) Netherlands [24] 45. Coprinellus phaeoxanthus A.R.P. Gomes & Wartchow (2016) Brazil [10] 46. Coprinellus plicatiloides (Buller) Voto (2020) n.r. [94] 47. Coprinellus pseudomicaceus (Dennis) Voto (2019) Brazil [36] 48. Coprinellus punjabensis Usman & Khalid (2021) Pakistan [95] 49. Coprinellus pusillulus (Svrček) Házi, L. Nagy, Papp & Vágvölgyi (2011) Hungary [33] 50. Coprinellus pyrrhanthes (Romagn.) Redhead, Vilgalys & Moncalvo (2001) n.r. [21] 51. Coprinellus radians (Desm.) Vilgalys, Hopple & Jacq. Johnson (2001) Armenia [6] Hungary [32] China [52] USA (North Carolina) [65] Germany [38] USA (Virginia) [88] Taiwan [96] Germany [39] Serbia [45] Brazil [36] Argentina [67] Sweden [13] 52. Coprinellus rufopruinatus (Romagn.) N. Schwab (2019) n.r. [65] 53. Coprinellus saccharinus (Romagn.) P. Roux, Guy García & Dumas (2006) Ukraine [17] Argentina [67] 54. Coprinellus sclerobasidium (Singer) Voto (2020) Argentina [67] 55. Coprinellus silvaticus (Peck) Gminder (2010) Hungary [32] Sweden [16] Iran [82] Serbia [45] Czech Republic [97] 56. Coprinellus subangularis (Thiers) Voto (2020) USA (Texas) [19] 57. Coprinellus subcurtus Voto (2019) USA (Hawaii) [55] 58. Coprinellus subradians Voto (2021) n.r. [54] 59. Coprinellus subrenispermus (Singer) Voto (2020) Argentina [67] 60. Coprinellus tenuis S. Hussain (2018) Pakistan [13] 61. Coprinellus tibiiformis Voto (2021) n.r. [54] 62. Coprinellus truncorum (Scop.) Redhead, Vilgalys & Moncalvo (2001) Serbia [46] Hungary [34] Iran [4] India [3] Argentina [67] Sweden [13] 63. Coprinellus valdivianus (Singer) Voto, Dibán & Maraia (2023) n.r. [68] 64. Coprinellus velutipes T. Bau & L.Y. Zhu (2024) China [59] 65. Coprinellus verrucispermus (Joss. & Enderle) Redhead, Vilgalys & Moncalvo (2001) Hungary [32] 66. Coprinellus xanthothrix (Romagn.) Vilgalys, Hopple & Jacq. Johnson (2001) USA (North Carolina) [39] Japan [73] Iran [82] Armenia [29] Germany [39] Serbia [45] Hungary [31] Netherlands [13] 67. Coprinellus xylophilus Voto (2021) Hungary [13] n.r., not reported. The distribution and diversity of Coprinellus species are influenced by the climate of their native regions and the abundant vegetation that provides the necessary nutrients for fungal growth. According to Schafer[26], Coprinellus mushrooms are saprotrophic fungi that grow on decaying plant material, such as wood, leaves, grass, and animal dung, primarily from ruminants. This ecological versatility enables the widespread distribution of Coprinellus mushrooms, as both temperate and tropical regions offer the requisite substrates, such as decaying organic matter and ruminant dung, ensuring the mushrooms' survival across diverse climates. In addition, efforts in extensive macrofungal identification and domestication play an important role in the abundant records of Coprinellus species, particularly in Europe. Accordingly, approximately 43.87% of the Coprinellus reports are from Europe, with only 29.68%, 24.52%, and 1.94% from Asia, the Americas (encompassing both North America and South America), and Africa, respectively (Fig. 4).

In comparison with the data from the present review, other studies have also reported different species of Coprinellus. For instance, the study of Doveri[8] on the occurrence of coprophilous Basidiomycetes and Ascomycetes in Italy recorded a total of 12 species of Coprinellus mushrooms. Meanwhile, the evolutionary and divergence study of Psathyrellaceae of Nagy et al.[32] utilizes 18 Coprinellus species in Hungary; however, seven of these species, particularly Coprinellus bisporus, Coprinellus callinus, Coprinellus congregatus, Coprinellus hiascens, Coprinellus pellucidus, Coprinellus sassii, and Coprinellus subpurpureus have been reclassified under the genus Ephemerocybe (Ephemerocybe bispora, Ephemerocybe callina, Ephemerocybe congregata, Ephemerocybe hiascens, Ephemerocybe pellucida, Ephemerocybe sassii, and Ephemerocybe subpurpurea, respectively) within the same family, Psathyrellaceae. In addition, 37 Coprinellus species utilize in different studies, specifically Coprinellus allovelus[9,28], Coprinellus amphithalus[18], Coprinellus angulatus[13,15,18,67,98], Coprinellus bisporiger[9,13], Coprinellus bisporus[8,13,29,99], Coprinellus brevisetulosus[8,13,67], Coprinellus callinus[13,18], Coprinellus canistrii[100], Coprinellus christianopolitanus[16], Coprinellus cineropallidus[13], Coprinellus cinnamomeotinctus[49], Coprinellus congregatus[8,34,101], Coprinellus doverii[8], Coprinellus eurysporus[13,102], Coprinellus fallax[21], Coprinellus furocystidiatus[23], Coprinellus hetersetulosus[8], Coprinellus heterothrix[9,34,49], Coprinellus hiascens[8,13,36,67], Coprinellus marculentus[8,42,98], Coprinellus minutisporus[28], Coprinellus mitrinodulisporus[28], Coprinellus pallidus[18], Coprinellus pellucidus[8,13,36,67], Coprinellus plagiosporus[13], Coprinellus pseudoamphitalus[28], Coprinellus pseudodisseminatus[12], Coprinellus radicellus[9,13,103], Coprinellus sublicola[18], Coprinellus sassii[8,13], Coprinellus sclerocystidiosus[13,18], Coprinellus singularis[21], Coprinellus subdisseminatus[42], Coprinellus subimpatiens[11,15,18,45,67], Coprinellus subpurpureus[34], Coprinellus uljei[13], and Coprinellus velatopruinatus[36] have also been reclassified under genus Ephemerocybe. Moreover, individual records of Coprinellus species, such as Coprinellus arenicola[27], Coprinellus ovatus[22], Coprinellus parvulus[24], and Coprinellus aureogranulatus[12] have also been reported in different countries. Notably, Hussain et al.[13] described three new species of Coprinellus in Pakistan (Coprinellus campanulatus, Coprinellus disseminatus-similis, and Coprinellus tenuis) and utilized a total of 25 species of Coprinellus from 97 sequences from the ITS datasets at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website to differentiate these three new species.

Despite these extensive records, taxonomic inconsistencies and outdated classifications persist in the literature. According to Voto[55], while working on a worldwide key to genera and species of the family Psathyrellaceae, several taxa were noted to have improper status, emphasizing the need to correct invalid species names in publications. Therefore, this present review, in line with the listing from Species Fungorum, provides an updated and corrected distribution of Coprinellus worldwide based on available reports.

Therefore, it is evident that the present review provides the most extensive accounts of Coprinellus species distribution to date. Notably, to the author's knowledge, this is the first comprehensive report on the global distribution of Coprinellus, offering valuable baseline data for future studies on their ecology, cultivation, and potential utilization. Given the widespread occurrence of these mushrooms across diverse climates and substrates, as highlighted in this review, such data are crucial for guiding conservation efforts, bioprospecting, and effective utilization in different industries.

-

Mushrooms are widely utilized as a source of food and traditional medicine worldwide, as they are known to contain essential nutrients, vitamins, minerals, mycochemicals, and mycocompounds have been shown to be beneficial to human health[30]. However, the edibility and nutritional benefits of most of the mushrooms were limited due to a lack of research. Therefore, continuous efforts to discover the nutritional composition of mushrooms and their biological compounds enable researchers to harness their beneficial nutrients. Accordingly, mushrooms are known to contain various bioactive compounds that are responsible for their distinct bioactivities. These compounds make mushrooms essential for many industries, including pharmaceutical, nutraceutical, and food industries, among others. According to Kour et al.[104], a variety of bioactive compounds, such as peptides, polysaccharides, proteins, polysaccharide-protein complexes, phenolic compounds, and terpenoids, have been identified in different types of mushrooms. Meanwhile, in the Philippines, approximately 15.53% of the macrofungal studies focused on elucidating the chemical composition of different mushroom species, particularly their proximate compositions, including protein, fats, moisture, fiber, and carbohydrates, as well as amino acid and fatty acid composition, and various mychochemicals[105].

Coprinellus, belonging to the phylum Basidiomycota and family Psathyrellaceae, was also explored for its various bioactive compounds, including its nutritional profile, polysaccharides, phenolic compounds, macroelements, microelements, fatty acids, and proteins, among others. According to Badalyan[30], many coprinoid mushrooms produce bioactive compounds, including polysaccharides, phenolics, and terpenoids, which have various beneficial effects, such as antimicrobial activity, immune modulation, antioxidant properties, cell growth stimulation, nematocidal activity, and antidiabetic activity. In the present review, 51 bioactive compounds, including sugar alcohol (one), fatty acids (four), phenolic compounds (six), flavonoids (22), hydroxycinnamic acid and derivatives (six), coumarins (three), organic acids (two), sugars (two), and sesquiterpenes (five) were recorded in eight species of Coprinellus, specifically C. curtus, C. disseminatus, C. domesticus, C. ellisii, C. micaceus, C. radians, C. truncorum, and C. xanthorix (Table 2). Additionally, in the study of Novaković et al.[44], the determination of amino acid composition, fatty acid profile, and mineral composition of C. dessiminatus was also recorded. Based on their findings, 17 amino acids (essential and non-essential), seven fatty acids (polyunsaturated, saturated, monounsaturated), three macroelements (K, Mg, and Ca), and four microelements (Cu, Zn, Mn, and Fe) were present in the methanolic extract of C. disseminatus. The total essential amino acids were 29.57 mg/g DW, with leucine being the most abundant, while non-essential amino acids totaled 96.69 mg/g DW. In addition, fatty acids consisted of 59.1% polyunsaturated, 23.1% saturated, and 17.9% monounsaturated, primarily linoleic (56.6%), palmitic (13.9%), and oleic acids (12.0%). Potassium was the most abundant macroelement, followed by calcium and magnesium, while iron dominated microelements[44].

Table 2. Bioactive compounds present in Coprinellus mushrooms.

Coprinellus species Sample type Bioactive compounds Ref. Coprinellus species Sample type Bioactive compounds Ref. C. curtus HPLC (water extract) Mannitol [30] C. truncorum Hot water extracts of fruiting body, submerged mycelia, and fermentation broth Apigenin [46] Stearic acid Baicalein Myristic acid Chrysoeriol C. disseminatus Crude ethanol (CdEtOH) and water extract (CdAq) Phenol [106] Vitexin Flavonoids Apigenin-7-O-glucoside Methanol extract Chrysoeriol [44] Luteolin-7-O-glucoside Luteolin7-O-glucoside Apiin Apigenin7-O-glucoside Baicalin Amentoflavone Quercetin p-Hydroxybenzoic acid Isorhamnetin p-Coumaric acid Quercitrin Protocatechuic acid Kaempferol-3-O-glucoside Chlorogenic acid Hyperoside HPLC (water extract) Mannitol [30] Quercetin-3-O-glucoside Fructose Naringenin Saccharose Catechin Oleic acid Epicatechin Stearic acid Amentoflavone C. domesticus HPLC (water extract) Mannitol [30] Daidzein Oleic acid Genistein C. ellisii HPLC (water extract) Mannitol [30] p-Hydroxybenzoic acid Stearic acid Protocatechuic acid C. micaceus HPLC (water extract) Mannitol [30] Vanillic acid Fructose Gallic acid Stearic acid Gentisic acid Myristic acid p-Coumaric acid HPLC (hot water extract) Protocatechuic acid [91] o-Coumaric acid Chlorogenic acid Caffeic acid (−)−Epicatechin Esculetin Naringin Scopoletin C. radians HPLC (water extract) Mannitol [30] Umbelliferon Fructose Quinic acid Oleic acid 5-O-Caffeoylquinic acid Stearic acid Ethanol extracts of the fruiting body and mycelia Apigenin [108] C. xanthorix HPLC (water extract) Mannitol [30] Baicalein Saccharose Chrysoeriol Oleic acid Amentoflavone Stearic acid Aqueous extract Crysoeriol [51] Myristic acid Apigenin-7-O-glucoside Coprinellus sp. Crude extract Coprinsesquiterpin A (1) [107] Luteolin-7-O-glucoside Coprinsesquiterpin B (2) Hyperoside Coprinsesquiterpin C (3) p-Hydroxybenzoic acid Coprinsesquiterpin D (4) Protocatechuic acid Coprinsesquiterpin E (5) Gallic acid p-Coumaric acid o-Coumaric acid Quinic acid 5-O-Caffeoylquinic acid Furthermore, an in vitro study by Novaković et al.[106] on the antiproliferative effects of C. disseminatus against the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line indicated a strong correlation between the total phenolic and flavonoid content and the cytotoxic activity. Therefore, C. disseminatus could be considered a potential alternative source of nutraceuticals and biologically active compounds. Likewise, Coprinsesquiterpenes, a new bisabolene-type sesquiterpene extracted from Coprinellus mushrooms, demonstrated anti-inflammatory effects, with IC50 values ranging from 12.8 μM to 34.7 μM in the Nitric Oxide (NO) inhibition assay[107]. Likewise, both the polysaccharides (PSH) and exopolysaccharides (ePSH) of C. truncorum demonstrated notable cytotoxic effects on human-derived HepG2 cancer cells[108].

Furthermore, aside from characterization, these bioactive compounds were also evaluated for diverse biological activities. According to Eguchi et al.[109], mushrooms contain various bioactive compounds with diverse health benefits, including antiviral, antidiabetic, antiparasitic, antibacterial, anti-hypercholesterolemic, and anticancer properties. Additionally, these compounds exhibit hepatoprotective, cardiovascular, energy-boosting, immune-modulating, and antioxidant effects. These advantageous properties are primarily attributed to the cellular components and secondary metabolites present in mushrooms, particularly those belonging to Basidiomycota[110]. Moreover, as noted by Ghora et al.[111], these medicinal properties are primarily derived from the fruiting body, culture mycelium, and culture broth of mushroom species.

Accordingly, the bioactivities of Coprinellus mushrooms, including C. disseminatus, C. micaceus, and C. truncorum, were assessed using different extracts and isolated bioactive compounds (Table 3). Notably, Coprinellus mushrooms exhibited 12 different bioactivities, including antifungal, promoting seed germination, biobleaching, antiproliferative, antioxidant, cytotoxic, lignocellulolytic, biotransformation of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxin, antidiabetic, anticholinesterase, anti-tyrosinase, and anti-inflammatory properties. For instance, the study by Nguyen et al.[91] evaluated four different bioactivities, specifically antidiabetic, antioxidant, tyrosinase, and NO inhibitory activities, as well as anticholinesterase activity, of the methanol and hot water extracts of the fruiting body of C. micacues. Accordingly, studies have revealed that the fruiting body of C. micaceus contains bioactive compounds exhibiting anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, α-glucosidase inhibitory, anti-tyrosinase, and anti-acetylcholinesterase activities, indicating their potential use in the pharmaceutical industry[91].

Table 3. Biological activity of Coprinellus mushrooms.

Coprinellus species Bioactivity Extract/compounds Findings Ref. C. disseminatus Promote seed germination n.r. Promote seed germination of Cremasta appendiculata up to 71.61% ± 0.92%. [53] Biobleaching C. disseminatus SH-1 NTCC-1163 (enzyme-A) and SH-2 NTCC-1164 (enzyme-B) Under solid-state fermentation, two newly developed low-cellulose xylanases (enzymes A and B) reduced the kappa number of wheat straw soda-AQ pulps by 24.38% and 27.94%, respectively, following XE treatment. [76] Antiproliferative Biomass ethyl acetate (BEA) extract The BEA extract exhibited antiproliferative activity (GI50 < 50 μg/mL) against all tested solid tumor cell lines (A549, HBL-100, HeLa, T-47D, WiDr), except for SW1573, which showed a slightly higher GI50 value of 52 μg/mL. [41] Antioxidant Biomass ethyl acetate (BEA) extract, and

Culture-broth Ethyl

acetate (CEA) extractIn the galvinoxyl radical assay, C. disseminatus (CEA) exhibited an antioxidant capacity of 10.281 ± 0.237 μM Trolox equivalents (TEAC). Meanwhile, in the ABTS assay, the BEA extract of C. disseminatus demonstrated the strongest activity, with a TEAC value of 126.67 ± 7.69 μM. [41] Antioxidant Crude ethanol (CdEtOH) The extract demonstrated strong superoxide anion scavenging activity (IC50 = 1.40 ± 0.66 μg/mL), followed by hydroxyl radical (7.37 ± 1.46 μg/mL) and FRAP (9.74 ± 0.79 μg/mL) scavenging. In contrast, it showed moderate nitric oxide (273.30 ± 21.53 μg/mL) and weaker DPPH (397.28 ± 64.17 μg/mL) scavenging effects. [106] Antioxidant Water extracts (CdAq). The extract demonstrated antioxidant activity, with the strongest activity against hydroxyl radicals (OH, IC50 = 4.02 ± 0.29 μg/mL) and FRAP reduction (4.02 ± 0.60 μg/mL). Moderate activity was observed for superoxide anion (SOA, 24.84 ± 2.38 μg/mL) and nitric oxide (NO, 21.28 ± 6.08 μg/mL), while DPPH scavenging was least potent (250.37 ± 15.74 μg/mL). [106] Cytotoxicity Crude ethanol (CdEtOH) The extract exhibited time and assay-dependent cytotoxicity against MCF-7 cells. In MTT assays, potency improved with prolonged exposure (24 h: IC50 > 249.47 ± 11.52 μg/mL; 72 h: 217.90 ± 24.79 μg/mL). Meanwhile, the effect of exposure time was observed in SRB assays, where the IC50 decreased from 511.37 ± 6.46 μg/mL (24 h) to 205.90 ± 35.98 μg/mL (72 h). Notably, the 72-hour results converged across both assays, indicating sustained exposure enhances cytotoxic efficacy regardless of the detection method. [106] Cytotoxicity Water extracts (CdAq) The cytotoxic effects on MCF-7 breast cancer cells were evaluated using MTT and SRB assays at different time points. In the MTT assay, the compound showed minimal cytotoxicity at 24 h (IC50 > 900 μg/mL) but exhibited moderate activity after 72 h of exposure (IC50 = 718.07 ± 37.36 μg/mL). The SRB assay demonstrated stronger concentration-dependent cytotoxicity, with IC50 values decreasing from 625.26 ± 26.80 μg/mL at 24 h to 211.01 ± 25.07 μg/mL at 72 h. These results indicate that the compound's anti-proliferative effects are both time-dependent and assay-dependent, with the SRB method showing greater sensitivity in detecting cytotoxic activity compared to the MTT assay. [106] Lignocellulolytic activity Xylanase and cellulase When cultured in a glucose-containing medium, the mycelium exhibited XLE and CLE activities of 815.074 ± 7.102 U/mL and 9.704 ± 0.030 U/mL, respectively. [69] C. disseminatus and

C. micaceusBiotransformation of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxin n.r. C. disseminatus achieved nearly complete degradation of dibenzo-p-dioxin (DD) within two weeks. Additionally, both C. disseminatus and C. micaceus converted 2,7-dichlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (2,7-DCDD) into a monohydroxylated derivative, suggesting the activity of the cytochrome P450 system in this process. [73] C. micaceus Lignocellulolytic activity n.r. Exhibited high production of cellulolytic enzymes, including endo-β-1,4-glucanase (0.69 ± 0.04 U/mL after 10 d with optimal pH 5.0) and endo-β-1,4-xylanase (1.17 ± 0.21 U/mL after 10 d with optimal pH 6.0), along with the lignolytic enzyme laccase (0.81 ± 0.20 U/mL after 28 d with optimal pH 3.0). This robust enzymatic activity indicates a strong potential for lignocellulose degradation. [90] Antioxidant Methanol and hot water extract Both methanol and hot water extracts exhibited lower DPPH scavenging activity than BHT but showed superior metal chelating effects at all concentrations. Their reducing power was also weaker than BHT at 0.125–0.2 mg/mL. [91] Antidiabetic Methanol and hot water (fruiting body) extract At a concentration of 2.0 mg/mL, the methanol and hot water extracts of C. micaceus reduced α-glucosidase activity by 62.26% and 67.59%, respectively. In comparison, acarbose, the positive control, showed an 81.81% inhibition at the same concentration. [91] Anticholinesterase Methanol and hot water extract In the AChE inhibitory assay, the methanol and hot water extracts of C. micaceus demonstrated 94.64% and 74.19% inhibition, respectively, at a concentration of 1.0 mg/mL. In comparison, galanthamine, the control drug, showed 97.80% inhibition at the same concentration. [91] Anti-tyrosinase Methanol and hot water extract At a concentration of 2.0 mg/mL, the methanol and hot water extracts exhibited strong tyrosinase inhibition, with rates of 91.33% and 91.99%, respectively. In comparison, kojic acid (the positive control) showed a higher inhibition rate of 99.61% at the same concentration. [91] Antioxidant (Nitric oxide inhibition) Methanol and hot water extract The methanol and hot water extracts dose-dependently suppressed nitric oxide (NO) production in lipopolysaccharide (LPS)- stimulated RAW264.7 cells. [91] C. truncorum Cytotoxicity Polysaccharide and exopolysaccharide Both PSH and ePSH demonstrated notable cytotoxic effects on human-derived HepG2 cancer cells (three-way ANOVA, p < 0.05). The C. truncorum PSH and ePSH were particularly effective, achieving a maximal reduction in cell viability of approximately 50% at 450 μg/mL after 24 h of treatment. [108] Anticholinesterase Polysaccharide extracts The polysaccharide extracts (PSH) from C. truncorum exhibited significant acetylcholinesterase (AChE) inhibitory activity, with an IC50 value of 0.61 mg/mL in liquid assays. [51] Antifungal MeOH (Fruiting body) The MIC and MFC values of CtMeOH extracts against Fusarium proliferatum BL1, Fusarium verticillioides BL4, Fusarium proliferatum BL5, and Fusarium graminearum were both found to be 198.00 mg/mL. In contrast, lower values of 99.00 mg/mL for both MIC and MFC were recorded for Alternaria padwickii (ALT). [112] Antifungal EtOH (Fruiting bodies) The CtEtOH exhibited a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 99.00 mg/mL against Alternaria padwickii (ALT) [112] Antioxidant Hot water extract The antioxidant activity of different fungal extracts was evaluated using DPPH radical scavenging and FRAP assays. The fruiting body extract exhibited moderate antioxidant activity, with a DPPH IC50 value of 65.90 ± 2.13 µg/mL and a FRAP value of 26.72 ± 0.47 mg AAE/g. In contrast, the submerged mycelium demonstrated significantly stronger antioxidant effects, showing a much lower DPPH IC50 (7.52 ± 2.46 µg/mL) and a higher FRAP value (30.63 ± 0.88 mg AAE/g), indicating greater free radical scavenging and reducing power. Meanwhile, the fermentation broth exhibited intermediate DPPH scavenging activity (IC50 42.39 ± 1.75 µg/mL) but the lowest FRAP value (6.03 ± 0.18 mg AAE/g), indicating a comparatively weaker reducing capacity. [46] Coprinellus sp. Anti-inflammatory Coprinsesquiterpin Coprinsesquiterpins 1–5 were tested for their ability to reduce inflammation in vitro by suppressing NO production in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. Among them, Coprinsesquiterpins 1, 3, and 5 showed significant anti-inflammatory effects, with IC50 values of 34.7, 27.1, and 12.8 μM, respectively. In contrast, Coprinsesquiterpins 2 and 4 were less effective, displaying IC50 values above 40 μM. [107] n.r., not reported. In summary, mushrooms, including species from the genus Coprinellus, are valuable sources of bioactive compounds with significant nutritional and medicinal potential. However, despite their promising applications in the pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, and food industries, research on Coprinellus remains limited, with only a few species being studied for their biochemical composition and bioactivities. The existing studies reveal that Coprinellus species contains essential amino acids, fatty acids, polysaccharides, phenolic compounds, and minerals, while also exhibiting diverse bioactivities, including antioxidant, antimicrobial, antidiabetic, and anti-inflammatory effects. Nevertheless, the full scope of their medicinal and nutritional benefits remains underexplored due to the lack of comprehensive research on most species within this genus. Thus, to fully utilize the potential of Coprinellus mushrooms, further biochemical and bioactivity studies are recommended on a broader range of species within this genus. Expanding research efforts will not only enhance the understanding of the medicinal and nutritional properties but also uncover novel bioactive compounds that could be utilized in various industries.

-

This review highlighted the distribution, biological compounds, and bioactivity of Coprinellus species worldwide. It presents a comprehensive checklist of 67 Coprinellus species, 51 different bioactive compounds, and 12 different bioactivities. The documented compounds and bioactivities establish an important foundation for the effective use of Coprinellus mushrooms in the nutraceutical and pharmaceutical industries. However, despite their rich bioactive potential, only eight species have been studied in detail.

Therefore, based on the compiled data, the following areas should be prioritized in future research:

(1) Conduct thorough studies on Coprinellus species, ensuring accurate characterization and classification using both morphological and molecular approaches.

(2) Additional species listing and optimization studies, especially for those countries with an ideal growing environment, favoring the growth of Coprinellus utilizing agro-industrial wastes and other cost-effective, locally available substrates.

(3) Isolate, characterize, and identify novel biological compounds in understudied and newly discovered Coprinellus species.

(4) Investigate additional biological activities across different models and elucidate their mechanism of action,

(5) Assess the edibility of various species of Coprinellus mushrooms through comprehensive chemical and toxicological analysis.

(6) Develop Coprinellus-based products, including functional foods, dietary supplements, and pharmaceutical drugs.

The authors are very grateful to the DOST-SEI Accelerated Science and Technology Human Resource Development Program-National Science Consortium (ASTHRDP-NSC) for the scholarship support that made this graduate study possible.

-

The authors confirmed their contributions to the paper as follows: Fabros JA and Dulay RMR conceptualized the paper; Fabros JA drafted the manuscript; Dulay RMR reviewed and edited the manuscript. Both authors approved the final version after reviewing the data.

-

Since no new data were generated or examined for this study, data sharing is not relevant to this article.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Fabros JA, Dulay RMR. 2025. Status review of the distribution, biological compounds, and bioactivity of Coprinellus (inky cap mushroom). Studies in Fungi 10: e026 doi: 10.48130/sif-0025-0024

Status review of the distribution, biological compounds, and bioactivity of Coprinellus (inky cap mushroom)

- Received: 07 July 2025

- Revised: 22 August 2025

- Accepted: 09 September 2025

- Published online: 18 November 2025

Abstract: Coprinellus mushrooms, belonging to the family Psathyrellaceae, are saprotrophic fungi that grow on decaying plant material, including wood, leaves, grass, and ruminant dung. These mushrooms are widely distributed and extensively studied worldwide. Given the potential of Coprinellus, this review aims to present their distribution, biological compounds, and bioactivities, highlighting their industrial applications and identifying gaps for future research. Accordingly, this review provides a comprehensive checklist of 67 Coprinellus species, with the USA representing the country with the highest number of recorded species. At the same time, Coprinellus disseminatus is identified as the most widely distributed species. Moreover, 51 bioactive compounds, including sugar alcohols, fatty acids, phenolic compounds, flavonoids, hydroxycinnamic acids and derivatives, coumarins, organic acids, sugars, and sesquiterpenes have been identified in eight Coprinellus species. Furthermore, 12 distinct bioactivities have been reported across three species, including antifungal, stimulation of seed germination, biobleaching, antiproliferative activity, antioxidant properties, cytotoxicity, lignocellulolytic activity, biotransformation of polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxin, antidiabetic potential, anticholinesterase activity, anti-tyrosinase effects, and anti-inflammatory properties. Overall, Coprinellus mushrooms are rich in bioactive compounds with significant nutritional and medicinal potential. The documented compounds and bioactivities provide a crucial foundation for their effective use in the nutraceutical and pharmaceutical industries. However, despite their rich bioactive potential, only eight species have been studied in detail. Therefore, further research is recommended to investigate novel bioactivities in other Coprinellus species and optimize their industrial applications.

-

Key words:

- Coprinellus disseminatus /

- Extract /

- Global occurrence /

- Mycochemicals /

- Psathyrellaceae