-

The humification process of lignocellulose plays a pivotal role in maintaining microbial community homeostasis, soil fertility, and carbon sequestration capacity[1−3]. For example, soil organic carbon from the humification process of lignocellulose, can serve as a carbon source, supplying metabolic energy for biological processes. Meanwhile, organic substances possess electron-donating and accepting capacities, enabling their involvement in affecting antibiotic resistance due to changes in ambient conditions[4].

Natural or artificial organic matter can enhance antibiotic resistance gene (ARGs) transformation due to the generation of reactive oxygen species, which can induce bacterial resistance[5,6]. For example, pesticides could exert selective pressure on sensitive strains, leading to the development of microbial community resistance to antibiotics[6]. Similarly, viruses are also affected by the change in organic matter in soil environments, which critically regulates microbial community composition and succession, improving environmental suitability[7]. In carbon-poor soils, viral auxiliary metabolic genes (AMGs) associated with organic carbon metabolism can significantly enhance host competitiveness and environmental adaptability via the 'Piggyback the Winner' ecological strategy[4]. The 'Piggyback the Winner' represents a novel symbiotic model between viruses and their microbial hosts. Viruses enhance the competitive advantage of their hosts through horizontal gene transfer while simultaneously ensuring their own sustained survival. This viral-mediated adaptive mechanism elevates the abundance of carbohydrate-active enzymes (CAZymes), thereby expanding the metabolic versatility of microbial hosts for complex organic compound utilization[8]. In addition, the composition of organic matter significantly influences ecological fitness. As is known, low molecular weight, readily biodegradable organic compounds are more easily assimilated and metabolized by microorganisms, thereby accelerating microbial activity[9]. Conversely, high molecular weight, recalcitrant organic substances persist in soil matrices for extended periods, limiting their bioavailability to microbial communities. Some deleterious compounds exhibit antimicrobial properties that disrupt microbial community structure and impair ecosystem homeostasis.

As a globally significant agricultural country, China incorporates vast quantities of crop residues into arable lands annually[10]. The main component of crop residues is lignocellulose, and it undergoes extensive natural degradation in terrestrial ecosystems. An estimated 5 billion Mg of lignocellulosic residue is decomposed annually worldwide[11]. However, current investigations have yet to comprehensively understand the ecological ramifications of these organic compounds from lignocellulose during the humification process, especially ignoring the environmental impacts of phenolic compounds. Elucidating molecular regulatory mechanisms is essential for developing future strategies to modulate soil ecological health. To elucidate the impacts of lignocellulose-derived organic matter, we simulated natural humification processes via hydrothermal liquefaction to fabricate artificial humic substances with different humification degrees[12]. These artificial humic substances were subsequently added to rice paddy soils to elucidate the mechanistic interactions among artificial humic fractions, carbon metabolism, and antibiotic resistance. Understanding these interactions is critical for predicting soil health and ecological risks associated with agricultural residue management.

-

Rice straw was dried and sieved through a 60-mesh sieve. Then, 15 g of rice straw and 210 mL of ultrapure water were added to a 500 mL autoclave for hydrothermal liquefaction. The autoclave was heated to the target temperatures (210, 270, and 330 °C) within approximately 1 h and maintained for 60 min with a stirring speed of 300 rpm. After the autoclave had cooled to room temperature, the mixture was filtered through a 0.45 μm PTFE film to obtain the artificial humic substances.

Characterizations of artificial humic substances

-

The total organic carbon (TOC) content of the artificial humic substances was measured using an analyzer (Multi 2100, Analytikjena, Germany). The molecular composition was partially analyzed by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS) (Agilent 5977B GC/MSD) with an HP-5MS column. The artificial humic substances were extracted by ethyl acetate to concentrate the organic molecular components. The GC oven temperature was programmed at a rate of 10 °C/min from 40 °C (held for 2 min) to 200 °C (held for 4 min), and then at a rate of 30 °C/min from 200 to 280 °C (held for 4 min). The carrier gas was helium with a 1 mL/min flow rate, and 1 μL of sample was injected at 300 °C. Molecular structures of artificial humic substances were comprehensively characterized using excitation-emission matrix (EEM) spectroscopy and Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry (FT-ICR MS). The EEM results were measured using a 3D fluorescence spectroscopy instrument (HORIBA Scientific, USA). The excitation (EX) and emission (EM) ranges were 239–800 nm with a 3 nm interval. The artificial humic substances were analyzed by FT-ICR MS according to the method described in previous literature[13].

The experiment of simulating the humification process in soil

-

Surface soil samples were collected from the Yaojingxi integrated crop-livestock family farm (Shanghai, 30.93° N, 121.17° E). Soil was air-dried and ground, and passed through a 2 mm sieve. After air-drying and grinding, soil samples were divided into 15 portions, each weighing 50 g of soil. To simulate the natural humification process in soil, artificial humic substances (HL210, HL270, HL330) with an identical TOC concentration (4,500 ppm) were added to the soil up to the maximum moisture content (the maximum moisture content was water saturation, about 60% in this soil). Deionized water was added to the soil as a control. Finally, the treated soil samples were incubated in a dark environment for two weeks at room temperature before being collected for testing. The incubation experiment was conducted in triplicate.

DNA extraction and metagenomic sequencing

-

A FastDNA™ SPIN Kit was used for extracting DNA from the microbiota in raw soil and treated soil samples. Paired-end sequencing was performed on an Illumina sequencing platform. A single read with an average length of 150 bp was generated for each end, yielding ~150 G of raw data. The quality of raw data was evaluated by FastQC v0.11.9, and low-quality reads and adapter sequences were filtered out using Trimmomatic v0.39 with the parameters LEADING:20, TRAILING:20, SLIDINGWINDOW:4:20, and MINLEN:70, yielding clean reads. Illumina reads were assembled into contigs using MEGAHIT v1.2.9 with the sensitive preset model (--min-count 1, --k-list 21, 29, 39, 49, ..., 129, 141). Binning of contigs was performed using MaxBin2 v2.2.7, CONCOCT v1.0.0, VAMB v3.0.2, and MetaBAT2 v2.0 with default parameters. DAS_Tool v1.1.7 was subsequently applied for the dereplication and consolidation of bins. The completeness and contamination of the bins were evaluated using CheckM v1.1.3, and bins with completeness < 50% and contamination > 10% were excluded. Taxonomic annotation of prokaryotic bins was conducted using GTDB-Tk v1.3.0, based on the Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB) Release 207.

Functional annotation of genes

-

Protein-coding genes were predicted using Prodigal (v2.6.2) with default parameters[14], and associated with KEGG IDs using EggNOG (v2.0.1–1) and DIAMOND (v0.9.22)[15]. High-quality (HQ) Illumina shotgun reads were mapped back to each ORF using Salmon v1.4.0 to quantify gene abundance (transcripts per million, TPM). To estimate the functions related to organic C metabolisms, the ORFs were annotated against the Carbohydrate-Active enZYmes database (CAZy database) using run_dbcan v4.1.4 with default parameters. The CAZy database was used, and antibiotic resistance genes were annotated based on the CARD database with USEARCH v.11.0 (- id 90, - evalue 1e−10).

In addition, HQ MAGs (Completeness > 90%, Pollution level < 10%) from binning were also analyzed with the CAZy database annotation to acquire MAGs-level gene annotation. Metagenomic sequences were submitted to the NCBI Sequence Read Archive database under the Bioproject accession number PRJNA892267. The completeness and contamination of the bins were evaluated using CheckM v1.1.3, and bins with completeness < 50% and contamination > 10% were excluded. Taxonomic annotation of prokaryotic bins was conducted using GTDB-Tk v1.3.0, based on the Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB) Release 207.

Identification of viral sequences, AMGs, and their hosts

-

To obtain viral sequences, VIBRANT v1.2.1 (default parameters) and VirSorter v2.2.3 (max_score ≥ 0.9) were used based on assembled contigs[16]. Then, viral contig quality was checked by CheckV. Those longer than 1 kb, with 95% identity and 80% coverage, were clustered into representative viral operational taxonomic units (vOTUs) using Stampede-ClusterGenomes. Further, vOTUs with a length ≤ 5 kb were filtered out to reduce false positives[17], except for those identified as complete circular genomes by VIBRANT v1.2.1 and CheckV v0.8.1. The abundance of vOTUs was also estimated using CoverM v0.7.0. The vOTUs were classified by PhaGCN2.0 based on the built-in database. VIBRANT and DRAM-v were used to identify potential AMGs in viral contigs, and the abundance of AMGs was calculated using Salmon v1.10.1[18].

Hosts of the virus were identified by homology matches, tRNAs similarity, and CRISPR spacer analysis[19]. The whole sequences, tRNA regions, and CRISPR spacer regions of vOTUs were searched against the high-quality MAGs recovered in this study. The BLASTn v2.5.0+ (coverage = 100, identity = 100), tRNAScan-SE v1.23, and CRISPRCasFinder were used to align sequences, identify tRNAs, and search for CRISPR spacers, respectively.

Statistical analyses

-

The statistical significance of disparities in MAGs and genes between non-treated and treated samples was evaluated via a two-sided Welch's t-test. A permutational multivariate analysis of variance was conducted using the adonis function to evaluate the effects of the treatments. Correlation analyses were conducted in Python to assess associations among CAZyme gene abundance, microbial taxa, antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), and viral populations. Data processing was performed using pandas, Spearman correlation coefficients were computed with scipy, and false-discovery-rate (FDR) correction was applied using statsmodels. Visualization and network construction were carried out with matplotlib, seaborn, and networkx.

-

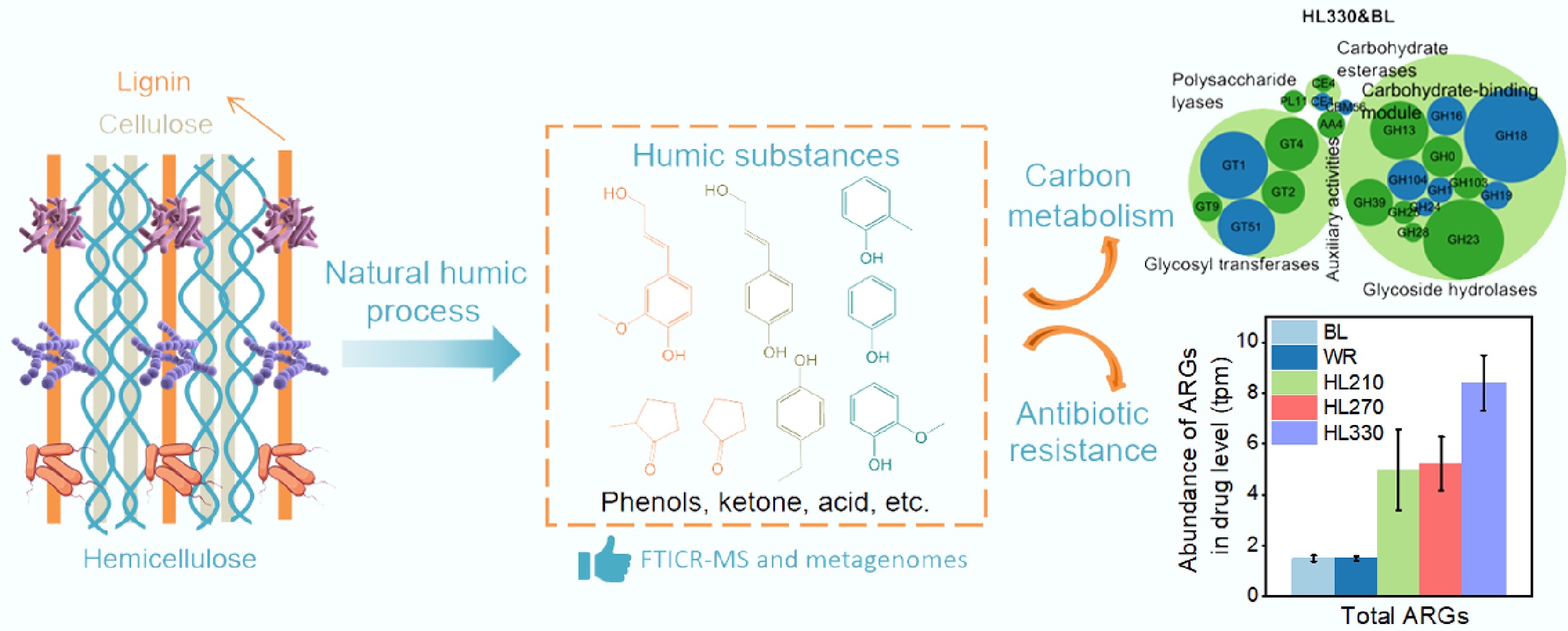

Biomass primarily consists of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin, which are decomposed by microbial activity during the natural humification process[11]. Accordingly, artificial humic substances were synthesized from rice straw (as a typical biomass), via hydrothermal liquefaction, and subsequently added to paddy soil to simulate the natural humification process (Fig. 1a)[12,20]. Artificial humic substances with varying degrees of humification, corresponding to different components, were synthesized at 210, 270, and 330 °C according to the color and total organic carbon (TOC) concentrations due to different decomposed temperatures of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin (Supplementary Fig. S1)[21,22]. EEM results indicated that the contents of fatty acids and humic-like substances were higher in humic substances prepared at 270 and 330 °C, because higher temperatures promote the decomposition of lignocellulose, especially for lignin[23]. The spectral region at Ex/Em wavelengths of 250–275/300–350 nm is associated with accessible and easily biodegradable compounds such as fatty acids[24]. Fluorescence peaks with Em > 380 nm usually represent humic-like substances[25]. To eliminate the effects of TOC concentration on soil, HL210, HL270, and HL330 with the same TOC concentrations (4,500 mg/L) were added to the paddy soil for a simulated humification process (Supplementary Fig. S2a). At the same TOC concentrations, the fluorescence intensity of humic-like substances was increased from 210 to 330 °C, because higher temperatures contributed to the transformation from lignocellulose to humic-like substances. Meanwhile, the phenol concentration increased with temperature due to the decomposition of lignin (Supplementary Fig. S2b & S2c)[22]. The predominant phenolic composition and content were validated by GC-MS results (Supplementary Table S1). In addition, ESI FTICR MS was employed to better characterize the composition and structure[26]. The relative abundances of lignins/CRAM-like structures, carbohydrates, and unsaturated hydrocarbons in HL210 were higher than those of other components. The Van Krevelen diagrams of HL270 and HL330 were similar, and exhibited a higher lipid content (Supplementary Fig. S3). Compared to HL210, Van Krevelen, and O/Cwa results also showed the transformation from a high value to a low value of the O/C ratio, indicating a lower polarity due to the deoxygenation reactions (Supplementary Figs S4−S6)[27]. H/Cwa and DBEwa results indicated a decreased degree of unsaturation. The reason may be that aliphatic products were produced at higher temperatures by a ring-opening benzene reaction, which was consistent with Van Krevelen diagrams. In addition, the relative abundances of the m/z distribution (200–400) in HL210 and HL330 were higher than in HL270, while the relative abundances of the m/z distribution (500–700) was lower. These results indicate that a temperature of 270 °C may be more favorable for facilitating the polymerization reaction[28]. Additionally, the abundance of lignins/CRAM-like structures decreased and shifted toward lipids and aliphatic compounds as a result of decomposition reactions at elevated temperatures (Fig. 1b; Supplementary Fig. S3). In summary, the natural humification process was simulated by employing different hydrothermal temperatures to selectively decompose hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin[29]. Lignins/CRAM-like structures were transformed to the lipids with increasing hydrothermal temperature, specifically producing higher concentrations of phenols, which can mediate interactions between natural humification processes and soil microbial communities. More importantly, compared to the water-treated soil, the total carbon content of soil treated with artificial humic substances (HL210, HL270, and HL330) was increased due to the introduction of organic matter, including humic acid and humin, significantly impacting the structure and function of the soil (Fig. 1c)[30]. The enhancement of soil organic carbon not only contributes to improved soil fertility but also facilitates carbon sequestration, thereby holding substantial practical significance[31]. In addition, the properties of treated soil, such as pH, Fe content, and CEC, were similar (Supplementary Table S2).

Figure 1.

Summary of artificial humic substances from rice straw by hydrothermal liquefaction. Three main components of biomass, including hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin, were decomposed at low, moderate, and high hydrothermal temperature. BL: Blank; WR: Water treatment; HLX represents the artificial humic substances prepared by hydrothermal liquefaction at different temperatures, and X represents the temperature. (a) Proposed strategy of hydrothermal liquefaction for simulating the natural humic process in soil. (b) Different component content of artificial humic substances by FTICR-MS analysis. (c) The humic substance content of treated soil amended with artificial humic substances.

Organic carbon metabolism in soils at the community level revealed by metagenomics based on the CAZy database

-

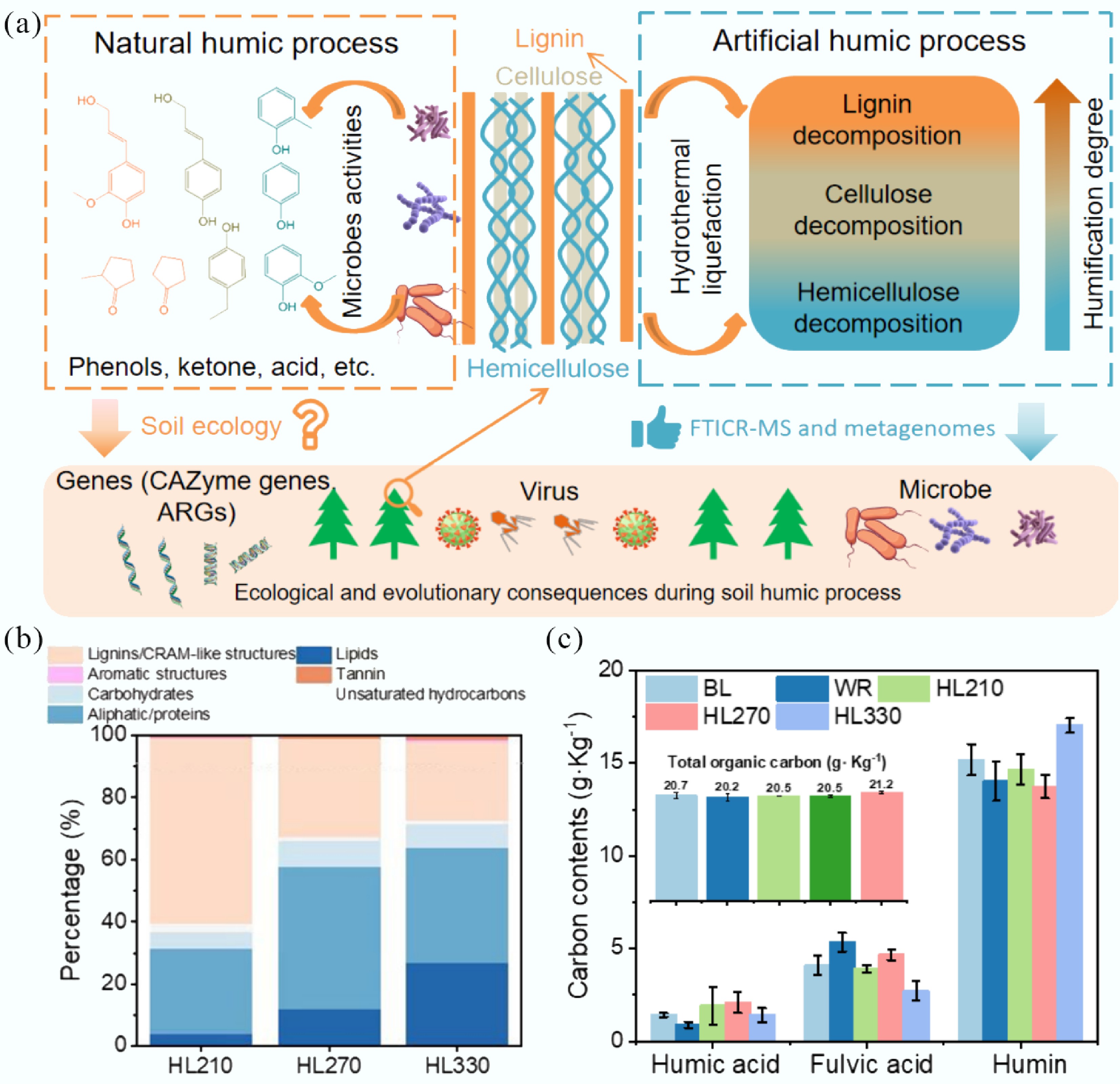

Carbon availability plays an important role in determining the microbial competitive interactions in soil[32]. Therefore, CAZyme genes were investigated in the soil treated with artificial humic substances. Results indicated that CAZyme gene abundance in glycosyl transferases (GT), glycoside hydrolases (GH), and carbohydrate-binding module (CBM) accounted for up to 97.8% of the total, as the predominant components, and the percentage of others was less than 1% (Fig. 2a). The relative proportion of GH, which is involved in the hydrolysis and rearrangement of glycosidic bonds increased from 60.95% to 83.71%, after soils were treated with HL210, HL270, and HL330. In contrast, the proportions of GT (involved in the glycosidic bond formation) and CBM (which facilitates the enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass) decreased from 32.15% and 5.78% to 12.31% and 2.88%, respectively. This is likely because organic matter can enhance the availability of carbon sources, thereby promoting microbial metabolic activity and facilitating the decomposition of organic compounds[33]. Especially for artificial humic substances synthesized at 330 °C, the abundance of GH was obviously increased. It is possible that the higher abundance of small molecules and low-polarity compounds was easily utilized by microorganisms (Supplementary Fig. S5; Fig. 2a)[34]. The enriched genes were further analyzed at the enzyme family level to elucidate the regulatory mechanisms of artificial humic substances on the CAZyme genes. Compared to BL, GH (four genes) and GT (one gene) in HL210, GH (five genes), GT (two genes), and CBM (two genes) in HL270, GH (six genes), GT (two genes), CE (one gene), and CBM (one gene) in HL330, were enriched, which indicated that artificial humic substances synthesized at higher temperature (270 and 330 °C) is beneficial to different types of CAZyme gene enrichment from (Fig. 2b; Supplementary Fig. S7). In addition, ten genera of Acidobacteria, four genera of Bacteroidetes, four genera of Candidatus Bathyarchaeota, seven genera of Chloroflexi, one genus of Euryarchaeota, nine genera of Firmicutes, four genera of Gemmatimonadetes, 57 genera of Proteobacteria, and two genera of Tenericutes contributed to the enriched CAZyme genes (Fig. 2c). Proteobacteria played a significant role in the enriched CAZyme genes. The enriched CAZyme genes in artificial humic substances-treated soil GHs (seven genes) were associated with oligo-saccharides, hemicellulose, polysaccharides, starch, cell wall components, chitin, peptidoglycan, and cellulose degradation. The enriched CEs (one gene) were associated with oligo-saccharides and hemicellulose degradation. The enriched CBMs (two genes) were associated with the integration of carbohydrates and enzymes for degradation. Meanwhile, the enriched GTs (two genes) were associated with the synthesis of cell membrane and cell wall components (Fig. 2d; Supplementary Table S3). These genes are mainly involved in cleaving various carbohydrate and glycoside bonds, oligo-saccharides, starch, hemicellulose, chitin, and cell wall component degradation, biosynthesis of the cell membrane and cell wall components, and catalytic conversion. These results demonstrate that different organic components derived from the humification process can alter microbial metabolism by modulating CAZyme gene abundance, thereby enhancing environmental adaptability.

Figure 2.

Summary of putative CAZyme genes in soils treated with artificial humic substances from rice straw by hydrothermal liquefaction. Three main components of biomass, including hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin, were decomposed at low, moderate, and high hydrothermal temperature. BL: Blank; WR: Water treatment; HLX represents the artificial humic substances prepared by hydrothermal liquefaction at different temperatures, and X represents the temperature. (a) Abundance of CAZyme genes at the class level. GT: glycosyl transferase; GH: glycoside hydrolase; CE: carbohydrate esterase; CBM, carbohydrate-binding module; PL: polysaccharide lyase; AA, auxiliary activities. The annotation of CAZyme genes was based on the Carbohydrate-Active enZYmes database using open reading frames (ORFs) from metagenomics. (b) Enriched CAZyme genes in treated soils amended with artificial humic substances. The response ratio was determined by calculating the natural logarithm of the ratio of the mean gene abundances between treated and untreated soil. (c) The relations of microbes contributing to the enriched CAZyme genes. The size of the circles and octagons indicate the contribution of microbes and gene abundance, respectively. (d) Potential substrates of enriched CAZyme genes. The related processes included biodegradation, biosynthesis and auxiliary activities. This information was sourced from the Carbohydrate-Active enZYmes database.

Viral AMGs and their host

-

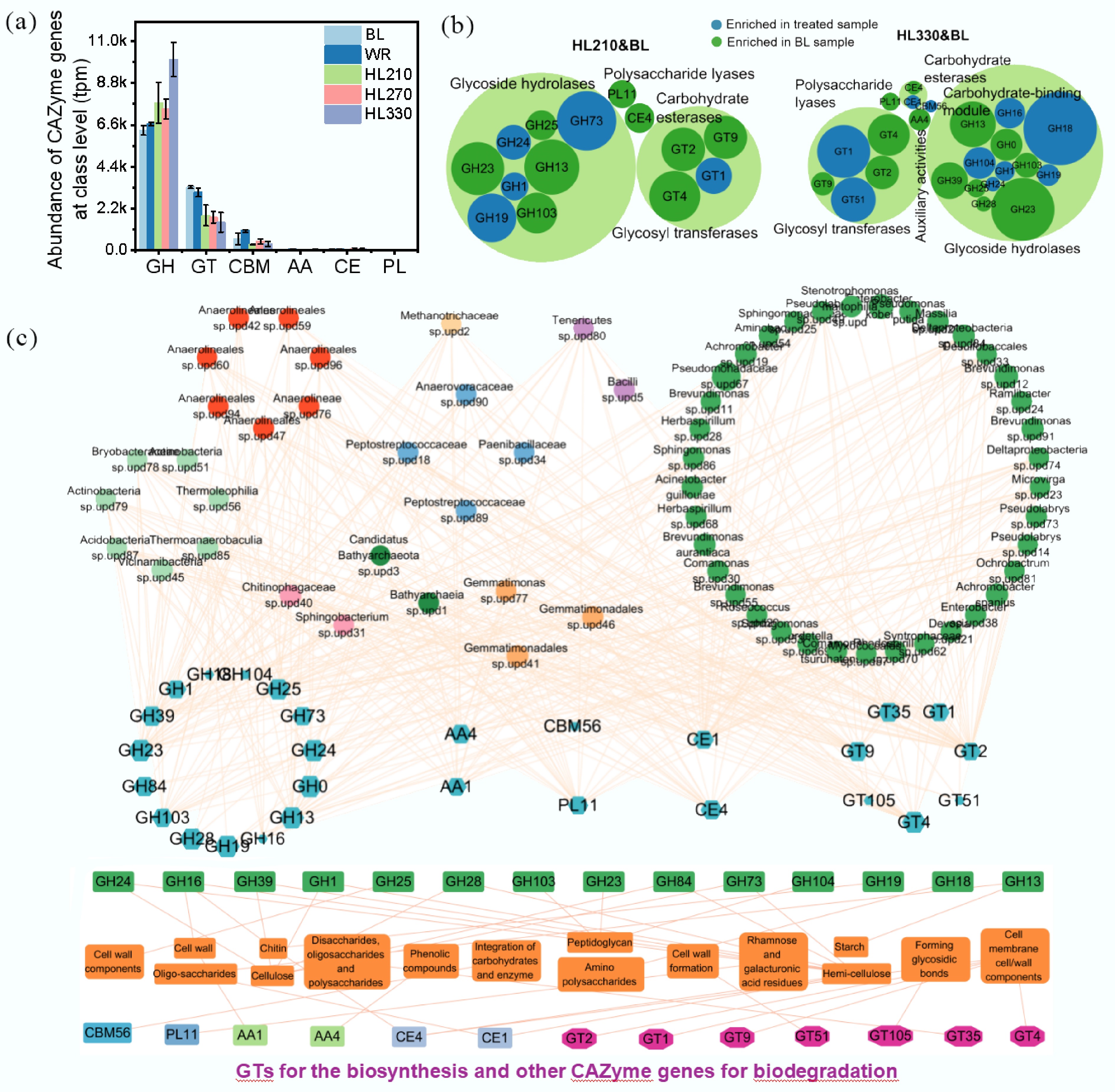

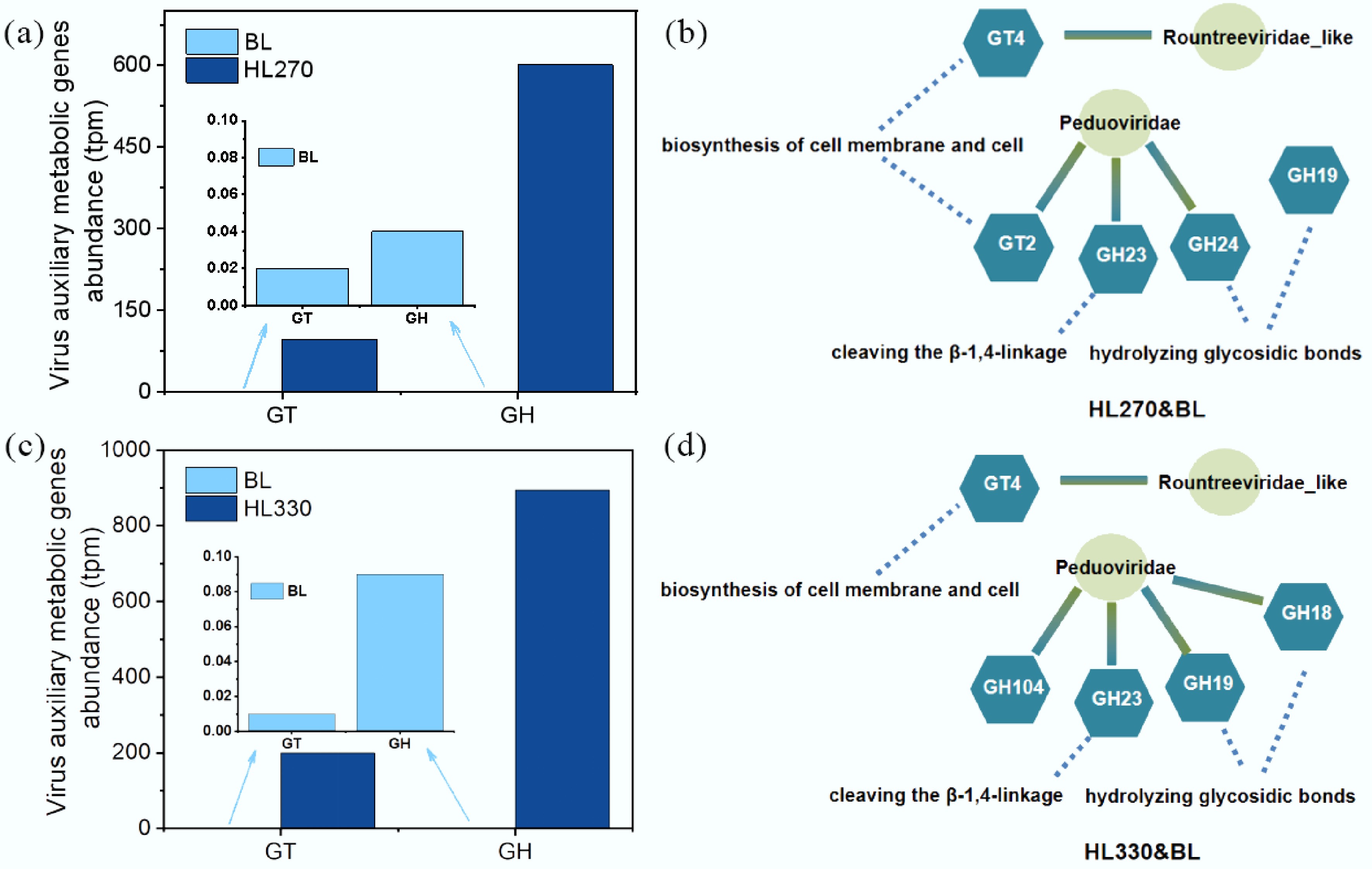

The abundance of CAZyme genes encoded by phage open reading frames (ORFs) was markedly increased after the soil was treated with artificial humic substances (Fig. 3a & b). Among the CAZyme class genes, the AMGs annotated as GT and GH classes were enriched in HL270 and HL330 treated soil, while there was no discernible alteration in HL210 treated soil. The degree of enrichment increased with increasing hydrothermal temperature, indicating the 'Piggyback the Winner' phenomenon. In HL270-treated soil, GT2 and GT4 were enriched, which are involved in the biosynthesis of cell membranes and cell walls. Similarly, GH19, GH23, and GH24 are involved in hydrolyzing glycosidic bonds within chitin (GH19), cleaving the β-1,4-linkage between N-acetylmuramyl and N-acetylglucosaminyl residues in peptidoglycan (GH23), and hydrolyzing the glycosidic bond between two or more carbohydrates, or between a carbohydrate and a non-carbohydrate moiety (GH24). Compared to the HL270 treated soil, the enriched genes remained largely consistent in HL330 treated soil, except for GT2, GH18, and GH104. GH18 can catalyze the biodegradation of β-1,4 glycosidic bonds in amino polysaccharides via a substrate-assisted retention mechanism[35]. As is known, the addition of more bioavailable small molecules and low-polarity compounds into the soil promotes the upregulation of microbial carbon metabolism genes (GH). Concurrently, as soil microorganisms gain access to increased carbon sources, they require additional biosynthetic activity to support cellular growth, thereby facilitating the enrichment of GT genes to accomplish this process. The marked enrichment of CAZymes observed in this study demonstrates a preferential microbial utilization of readily mineralizable carbon substrates. This metabolic shift may enhance the turnover of soil organic carbon and consequently contribute to soil carbon sequestration. In HL270-treated soil, AMGs annotated as GT2, GH23, and GH24 originated from Peduoviridae, GT4 was produced from Rountreeviridae_like, while those annotated as GH19 were derived from viruses that remain unclassified. Similarly, AMGs annotated as GH18, GH19, GH23, and GH104 originated from Peduoviridae in HL330-treated soil (Fig. 3c & d).

Figure 3.

Summary of viral AMGs in soils treated with artificial humic substances from rice straw by hydrothermal liquefaction. Three main components of biomass, including hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin, were decomposed at low, moderate, and high hydrothermal temperature. BL: Blank; WR: Water treatment; HLX represents the artificial humic substances prepared by hydrothermal liquefaction at different temperatures, and X represents the temperature. (a), (b) Abundance of viral AMGs annotated as CAZyme genes at the class level. The annotation of CAZyme genes was based on the Carbohydrate-Active enZYmes database using AMGs identified from viral sequences. (c), (d) Viruses contributing to the enriched AMGs annotated as CAZyme genes.

Antibiotic resistance in soils at the community level

-

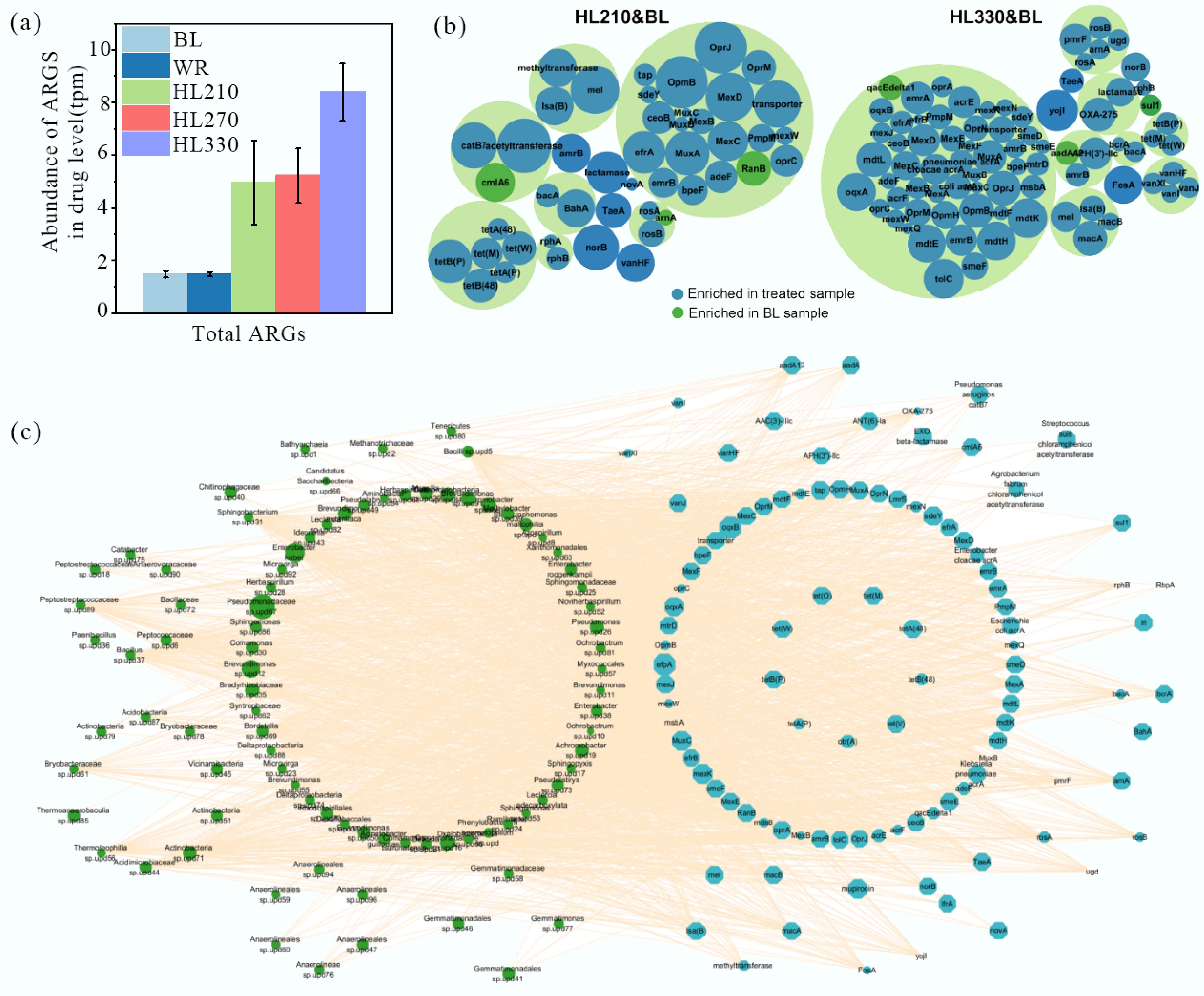

The abundance of ARGs was observably increased in artificial humic substances-treated soil, especially in the soil treated with the artificial humic substances from higher temperatures (Fig. 4a). Compared to BL soil, the abundance of total ARGs increased by 2.3-fold in HL210 treated soil, 2.5-fold in HL270 treated soil, and 4.6-fold in HL330 treated soil. This is a particularly intriguing phenomenon; it was observed that artificial humic substances (HL330) produced at elevated temperatures contain higher levels of phenolic compounds (Supplementary Fig. S2). Some studies have reported that phenolic substances can induce greater microbial antibiotic resistance under environmental oxidative stress, thereby promoting the accumulation of ARGs[36,37]. Therefore, phenolic substances were correlated with an increased abundance of ARGs in soil[36]. The role of lignocellulose-derived phenolic compounds in promoting the proliferation of ARGs has been rarely noticed and discussed during the natural humification process[4,12]. The main ARGs contained multidrug, bacitracin, puromycin, rifamycin, beta_lactam, macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin, aminoglycoside, tetracycline, fosfomycin, novobiocin, and vancomycin. The relative abundance of these ARGs comprised 96.2% of the total ARGs, and that of other ARGs was less than 1% (Supplementary Fig. S8). The ARGs abundance was evidently increased, especially for defensin, pleuromutilin_tiamulin, bacitracin, polymyxin, fosfomycin, and multidrug in treated soils. Twenty five ARGs, 27 ARGs, and 54 ARGs related to antibiotic efflux, eight ARGs, 10 ARGs, and 13 ARGs related to antibiotic target protection; and six ARGs, six ARGs, and five ARGs related to antibiotic inactivation were identified as enriched ARGs in the soil treated with HL210, HL270, and HL330, respectively (Fig. 4b; Supplementary Fig. S9 and Supplementary Tables S4–S6). Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria, Firmicutes, and Chloroflexi mainly contributed to the enrichment of ARGs (Fig. 4c). The average abundance of enriched ARGs was 114.7% higher in soil treated with HL210, 182.1% higher in soil treated with HL270, and 710.5% higher in soil treated with HL330 than that in soil treated with BL. These results indicated that ARGs were easily enriched in soil treated with artificial humic substances, and the degree of enrichment was increased with higher hydrothermal liquefaction temperature.

Figure 4.

Summary of putative ARGs in soils treated with artificial humic substances from rice straw by hydrothermal liquefaction. Three main components of biomass, including hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin, were decomposed at low, moderate, and high hydrothermal temperature. BL: Blank; WR: Water treatment; HLX represents the artificial humic substances prepared by hydrothermal liquefaction at different temperatures, and X represents the temperature. (a) Abundance of ARGs at the drug level. The annotation of ARGs was based on the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database using open reading frames (ORFs) from metagenomics. (b) Enriched ARGs in treated soils amended with artificial humic substances. The response ratio was determined by calculating the natural logarithm of the ratio of the mean gene abundances between treated and untreated soil. (c) The relations of microbes contributing to the enriched ARGs. The size of the circles and octagons indicate the contribution of microbes and gene abundance, respectively.

MAGs analysis in soils

-

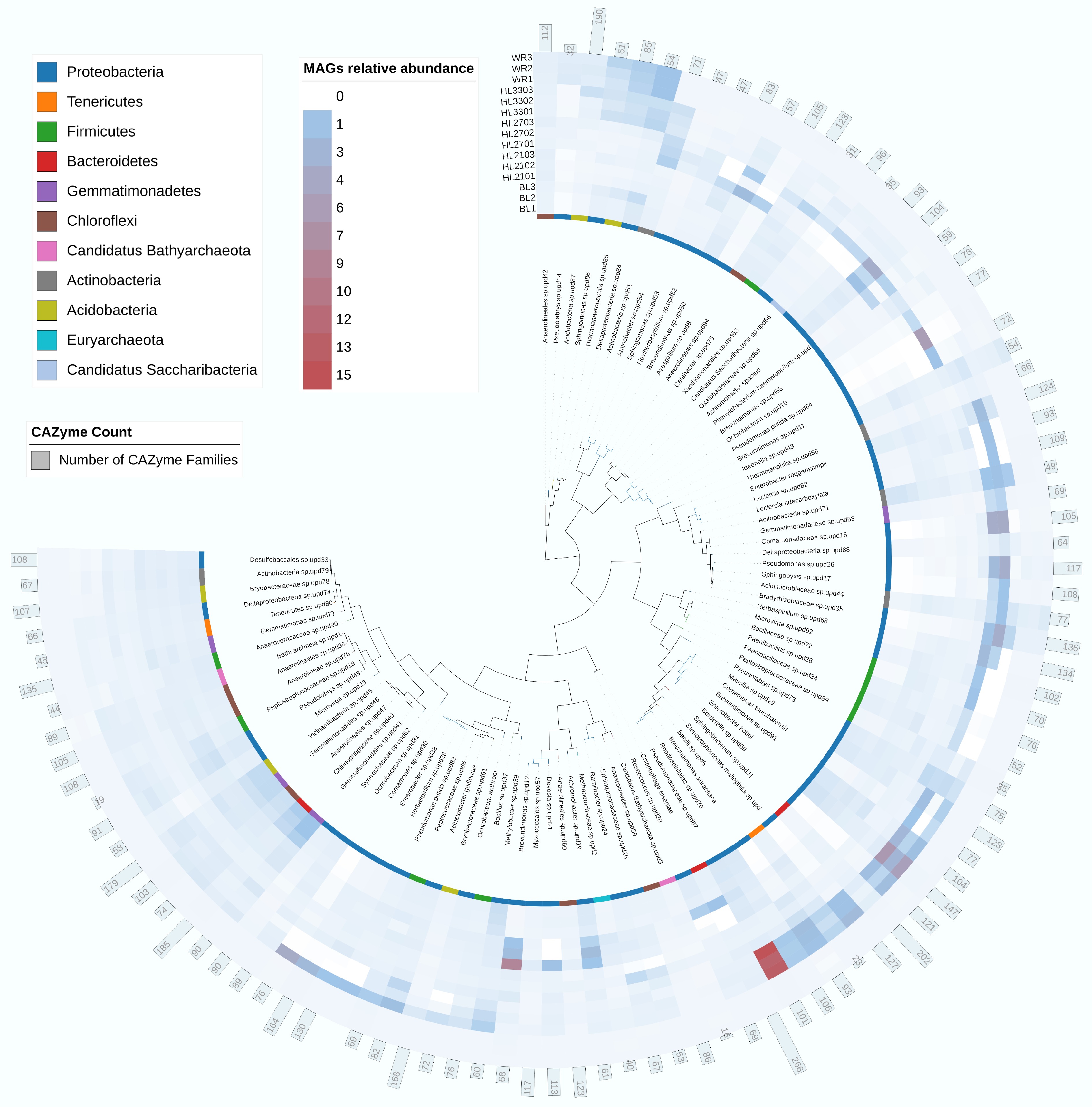

There were 96 MAGs in all soil samples based on metagenomic data (Fig. 5), and these MAGs mainly contained Proteobacteria (68%), Acidobacteria (9.3%), Firmicutes (6.9%), Chloroflexi (5.2%), and Gemmatimonadetes (3.8%). Proteobacteria exhibited the most significant contribution according to the results of enriched CAZyme genes and ARGs (Figs 2c & 3c). Meanwhile, it was found that the Pseudomonadaceae sp. upd67 and Enterobacter kobei were obviously enriched in HL330-treated soil.

Figure 5.

Summary of metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) in soils treated with artificial humic substances from rice straw by hydrothermal liquefaction. Three main components of biomass, including hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin, were decomposed at low, moderate, and high hydrothermal temperature. BL: Blank; WR: Water treatment; HLX represents the artificial humic substances prepared by hydrothermal liquefaction at different temperatures, and X represents the temperature. Each sample was analyzed with three replicates.

-

The natural humification process is ubiquitous in soils, wherein biomass is gradually transformed into complex organic compounds that significantly influence soil environments. In this study, the natural humification process was approximatively simulated for revealing the impact of humification on the soil environment. Lignins/CRAM-like structures were converted into lipids with increasing hydrothermal temperature through decomposition reactions, especially producing higher concentrations of phenols from lignin. The influx of bioavailable small molecules into the soil promoted the upregulation of microbial carbon metabolism genes (GH). Concurrently, soil microorganisms strengthened biosynthetic activity to support cellular growth by facilitating the utilization of carbon sources. Importantly, higher concentrations of phenols contributed to the enriched ARGs, suggesting a natural mechanism for the environmental enrichment of ARGs. Additionally, viral auxiliary metabolic genes increased host environmental adaptability through the 'Piggyback the Winner' strategy, such as enriching the GH and GT genes. This study provides an understanding of the microbial communities responding to soil organic matter during humification processes, and a potential strategy for improving the soil environment, especially in regulating carbon metabolism and antibiotic resistance.

-

It accompanies this paper at: https://doi.org/10.48130/aee-0025-0010.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: all authors contributed to the study conception and design; conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, supervision, and writing-review & editing were performed by Yujun Wang and Xiangdong Zhu; conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, and writing-original draft were performed by Fengbo Yu, Mengyuan Ji; validation and writing-review & editing were performed by Yong Jiang, Zhiwei Liang, Jiewen Luo, Chao Jia, Qicheng Xu, Baoshan Xing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22276040).

-

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

-

The natural humification process was simulated by hydrothermal liquefaction.

Lignocellulose-derived humic substances contributed to the enrichment of CAZyme genes (glycoside hydrolases).

High temperature contributed to the production of higher concentrations of phenols.

The abundance of ARGs increased due to the higher concentration of phenols.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Fengbo Yu, Mengyuan Ji

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - The supplementary files can be downloaded from here.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yu F, Ji M, Jiang Y, Liang Z, Luo J, et al. 2025. Lignocellulose-derived natural humic substances modulate carbon metabolism and antibiotic resistance. Agricultural Ecology and Environment 1: e010 doi: 10.48130/aee-0025-0010

Lignocellulose-derived natural humic substances modulate carbon metabolism and antibiotic resistance

- Received: 25 August 2025

- Revised: 07 November 2025

- Accepted: 18 November 2025

- Published online: 05 December 2025

Abstract: Lignocellulose-derived humic substances play a pivotal role in modulating soil environments, such as constituting a significant carbon reservoir and influencing microbial adaptations. However, the impact of lignocellulose-derived humic substances remains poorly understood. Humic substances were synthesized by hydrothermal liquefaction of biomass at different temperatures, and then added to the soil to simulate the natural humification process. Results show that humic substances from higher temperatures (270 and 330 °C) acted as a carbon source and contributed to the enriched CAZyme genes (glycoside hydrolases) for hydrolysis and rearrangement of glycosidic bonds. Importantly, the abundance of enriched antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) increased and was correlated with the higher concentration of phenols from lignin at 270 and 330 °C, suggesting a noteworthy phenomenon for ARG enrichment during the natural humification process. Viral auxiliary metabolism also increased host environmental adaptability through the 'Piggyback the Winner' strategy, such as enriching genes for glycoside hydrolases and glycosyl transferases at higher temperatures. Therefore, soil microorganisms can adapt to environmental changes by modulating their metabolic pathways in response to organic matter composition. This study provides critical insights into ecological shifts during humification processes in natural environments.