-

Grape wine is one of the most global widely known and appreciated alcoholic beverages. Moderate consumption may have some beneficial effects on human health due to the high antioxidant activity of wine[1]. Aroma, taste, and appearance are three important indicators to evaluate food quality[2]. Among them, the aroma profile of wine is one of the key factors influencing its quality[3]. Understanding consumer preferences and predicting their behavior is a difficult task for the wine industry. Previous studies[4−10] have documented the organoleptic characteristic such as aroma appreciated by wine consumers. Grape wine is a complex matrix consisting of a wide range of volatile and non-volatile compounds[11]. Although the overall composition of most grape cultivars is very similar, there are distinct aroma and flavor differences between most varieties. These differences can mostly be attributed to relatively minor variations in the proportion of the compounds that constitute the aroma profile of the grape[12]. Especially, the varietal component derived from grape aroma and aromatic precursors, impart specific aroma depending on the cultivars characteristics[13,14] Further, wine flavor is also dependent on fermentation process, storage and aging. The most important aroma substances of wine have been identified as alcohols, esters, aldehydes, ketones, acids, terpenes[15], ethers, lactones, pyrazines, phenolic compounds[16] and sulfur containing compounds. These sulfur-containing compounds can have either a positive or negative impact on the aroma and flavor of wine, compounds such as 3-mercaptohexanol can impart fruity flavors to a wine[17]. Although some of these compounds are present at low concentrations in the grape wine, they normally have a huge impact on the overall aroma profile[18].

Grape wine is well-known for its health benefits, and most of them are, at least partially, attributed to the presence of phenolic compounds. It has been reported that moderate consumption of alcoholic beverages, especially wine, could protect from cardiovascular disease. This phenomenon defined as the French paradox was proposed for the first time by Serge Renaud[19]. The phenolic compounds originate from original grape and/or formed during alcohol fermentation. Additionally, volatile substances present in concentrations at below their perception threshold may contribute to the final wine aroma and flavor palette by interactive effects with each other in various ways other compounds in wine[20]. Studies also showed that when the ethanol concentration in wine was lowered to 7%, a significant increase in the intensities of the fruity, flowery, and acid flavors and aromas was seen[21].

Flavor is responsible for the overall distinctive sensory properties of grape wine, and is vital in the evaluation of quality. The subtle differences that distinguish one varietal wine from another may depend on the concentration and types of the volatile and non-volatile substances. The quality of wine can be evaluated through both chemical and sensory analysis. The most widely accepted chemical analytical method to detect, identify and quantify flavor compounds is GC-MS combined with HS-SPME for its high selectivity, sensitivity and precision[22−24]. Equipments such as electronic nose and electronic tongue consisting of an array of sensors are widely applied to detect flavor of food by simulating the olfaction and taste of humans with the advantages of excellent selectivity, high sensitivity, less time-consuming and relatively lower price[25]. Among them, gas sensor arrays are referred to as electronic nose, with partial specificity and an appropriate pattern-recognition system, while chemical sensor arrays are defined as electronic tongue, identifying the five basic tastes (sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and umami)[26]. Depending on the sensing materials, gas sensors of E-nose can be classified into several types including, metal-oxide semiconductor (MOS), conducting polymers (CP), quartz crystal microbalance (QCM), and surface acoustic wave (SAW) sensors[27]. Among them, MOS gas sensor is most widely used for E-nose, it was reported that MOS sensors are sensitive to hydrogen and unsaturated hydrocarbons or solvent vapors containing hydrogen atoms[25]. The common E-tongue has the following types: potentiometry, voltammetry, and impedance spectroscopy[28]. E-tongue can detect the overall taste of food, they cannot identify specific compounds. Taste-active compounds, such as free amino acids (FAAs), were responsible for the characteristic taste of grape wines and also act as precursors to the formation of aromas. Thus, the individual taste compounds can be determined by amino acid detection. Currently, E-nose and E-tongue have been widely researched on quality evaluation of red wine. The E-Nose was revealed like a powerful tool for the objective differentiation of the wines obtained from the authorized grape variety in a Protected Denomination of Origin[29]. A multi-sensor fusion technology based on a novel low-cost E-nose and a voltammetric E-tongue was developed to classify red wines that differ in geographical origins, brands, and grape varieties[30]. Compared to GC-MS, E-noses do not provide information on the quantity of the individual volatile compounds but rather a global analysis of the volatile chemical profile so-called 'fingerprints', which is more similar to the human olfactory perception[31,32].

There is a growing interest in developing rapid methods for the analysis of organoleptic properties of grape wine such as aroma and taste which play a crucial role in consumer preferences and choices[33]. Therefore, accurately and efficiently identifying different wines are of particular importance. In addition, it is important for quality control, storage, and brand recognition as well. In the literature, different methods for wine age prediction[34,35], the influence of grape maturity on wine volatiles and the optimum drying time of the grape to produce sweet wines of higher aromatic quality[36] were investigated. However, there are no systematic studies describing the combined application of HS-SPME-GC-MS, E-nose, E-tongue, HPLC and amino acids analyzer in grape wines flavor studies. Hence, we set up a comprehensive method to analyze the flavor of commercially available grape wines (Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Gernischt, Shiraz, Merlot, Pinot Noir, Tempranillo and Chardonnay). Principal component analysis (PCA) of E-nose and E-tongue was applied to analyze the difference in volatile and non-volatile organic compounds of grape wines. The combination of flavor chemistry with sensory analysis techniques could provide a comprehensive odor and taste characterization of wines, which could provide an effective method for consumers to choose their preferred grape wines. The information obtained in this study would have important referential value for the flavor research of grape wines.

-

By researching the types of grape wines sold in the local supermarket in Nanjing, China, 17 commercially available grape wines from seven different grape varieties (Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Gernischt, Shiraz, Merlot, Pinot Noir, Tempranillo and Chardonnay) were studied as experimental samples (Table 1). HPLC grade methanol, acetic acid, ethyl acetate and phenolic acid standards (gallic acid, protocatechuic acid, vanillic acid, catechin, caffeic acid, syringic acid, p-coumaric acid and ferulic acid) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Company (St. Louis, MO, USA). Water was purified on Simplicity system (Millipore) to prepare the aqueous solutions.

Table 1. The details of the grape wines utilized in the experiment.

Sample number Grape wine varieties Country of origin Alcohol content

(V/V %)1 Cabernet Sauvignon-A China 12.0 2 Cabernet Sauvignon-B China 13.0 3 Cabernet Sauvignon-C China 12.5 4 Cabernet Sauvignon-D China 12.0 5 Cabernet Sauvignon-E France 12.0 6 Cabernet Gernischt-A China 12.5 7 Cabernet Gernischt-B China 12.5 8 Shiraz-A China 13.0 9 Shiraz-B Australia 14.5 10 Pinot Noir-A China 13.0 11 Pinot Noir-B China 12.0 12 Merlot-A Australia 13.5 13 Merlot-B Australia 14.0 14 Merlot-C Australia 13.8 15 Merlot-D China 12.5 16 Tempranillo Spain 13.0 17 Chardonnay Australia 13.0 Methods

HS-SPME-GC-MS analysis

-

The volatile compounds of grape wine were determined using HS-SPME-GC-MS according to the reported methods[37] with slight modification. The methods have been proved to develop a derivatization protocol for untargeted GC-MS analysis.

Grape wine (10 mL) was mixed with 2.0 g sodium chloride. The mixture was placed in a 20 mL headspace vial, and stirred at 40 °C for 30 min. To extract volatile compounds from grape wine, a 50/30 µm (DVB/CAR/PDMS) fibre (Supelco, Bellefonte, USA) was used which was preconditioned at 250 °C for 10 min. The fibre was exposed to the sample headspace and extracted at 40 °C for 40 min. After extraction, the fibre was inserted into the splitless injector of the GC-MS (7890A-5975C, Agilent, USA) to identify the volatile compounds. The gas chromatograph was equipped with a 5% phenylmethyl silicone capillary column (HP-5, 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm, Agilent, USA). The injector temperature was 250 °C. The carrier gas was helium at a constant flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Analysis was carried out in the electronic impact mode at 70 eV. The temperature of ionization source and quadrupole was 250 °C and 150 °C, respectively. Detection was performed in full scan mode, from 29 aum to 550 aum. The identification was determined using the NIST.08 libraries and the minimum matching requirement was 80%. The relative content was calculated on the basis of peak area percentage. Each sample was measured in triplicate.

Analysis of phenolic compounds using HPLC

-

The extraction method of phenolic compounds referred to Caceres-Mella et al.[16]. Phenol analysis was carried out with HPLC (LC-20AD, Shimadzu, Japan).The HPLC system consists of a diode array detector (SPD-M20A), autosampler (SIL-20A) and a column oven (CTO-20A). HPLC assay was conducted as described by Beta et al.[38] with some modifications. Their analysis results verify the validity and universality of the method. 250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 µm ZORBAX SB-C18 (Agilent, USA) was used for separation. The mobile phase consisted of A (0.1% acetic acid in water) and B (0.1% acetic acid in methanol), and the flow rate was 0.9 mL/min. The contents of phenolic compounds were quantified using external calibration curves. The gradient elution program was as follow: 91%–86% A for 0–11 min, 86%–85% A for 11–17 min, 85%–81% A for 17–28 min, 81%–72% A for 28–38 min, 72%–60% A for 38–46 min, 60%–30% A for 46–65 min, and 30%–91% A for 65–75 min. The column oven temperature was held at 30 °C. The injection volume was set to 20 μL and detection wavelength was 280 nm. Analyses were performed in triplicate.

Analysis of free amino acids

-

The procedures were conducted according to the published literature by Xia et al.[39]. Ten mL grape wine sample was mixed with 10 mL sulfosalicylic acid (10%) to precipitate protein and then centrifuged at 4 °C for 20 min (10,000 rpm/min). Subsequently, the supernatants were filtered with a 0.45 µm micro-pore filter membrane. The content of free amino acids in grape wines was detected by automatic amino acid analyzer (L-8900, Hitachi Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) with a column packed with Hitachi custom ion-exchange resin 2622 (4.6 mm × 60 mm, particle size 5 μm) and then calculated by calibrating with standard amino acids (0.1 μmol/mL). Twenty µL sample solution was injected into the automatic analyzer to obtain the peak area of each amino acids in grape wine. Each sample was measured in triplicate. Quantitation was analyzed by an external standard method and the content of amino acids in the sample was calculated by the formula as follows:

$ {\mathrm{M}}_{\mathrm{i}}=\frac{{\mathrm{X}}_{\mathrm{i}}\times \left({{\mathrm{V}}_{\mathrm{W}}+\mathrm{V}}_{\mathrm{S}}\right)}{{\mathrm{V}}_{0}\times {\mathrm{V}}_{\mathrm{w}}} $ Where Mi (mg/L) is the content of amino acid 'i' in samples, Vs (mL) is the volume of sulfosalicylic acid, Xi (ng) is the concentration of amino acid 'i' detected by the instrument, V0 (μL) is the injection volume, and Vw (mL) is the volume of the wine sample.

Analysis of E-nose

-

The analysis of grape wine was performed with a portable electronic nose PEN 3, (Airsense Analytics GmbH, Germany) which was composed of an array of 10 metal oxide semiconductors (MOS). The response characteristics of each sensor were shown as follows: W1C (aromatic compounds); W5S (nitrogen oxide); W3C (ammonia and aromatic compounds); W6S (hydrogen); W5C (olefin and aromatic compounds); W1S (hydrocarbons); W1W (hydrogen sulphide); W2S (alcohols and partially aromatic compounds); W2W (aromatic compounds and organic sulphides); W3S (alkanes (methane, etc.). E-nose was applied to identify different volatile species. The pattern recognition software (Win Muster v.1.6.2) was used for data recording and elaboration.

The E-nose analysis was conducted according to a method of Liu et al.[40], 10 mL grape wine was injected into a headspace vial of 40 mL volume and equilibrated at 25 ± 2 °C for 30 min to reach a steady state. The headspace gas was pumped through the sensor array for 80 s (injection time) with a flow rate of 300 mL/min. After sample analysis, the system was purged for 100 s with filtered air to enable the signals to return to the baseline. Each sample was measured in triplicate.

Analysis of E-tongue

-

This experiment was conducted with the Taste-Sensing System SA402B (Intelligent Sensor Technology Co. Ltd. Japan) according to the method from Liu et al.[40]. This E-tongue system was comprised of reference electrodes (Ag/AgCl), auto-sampler, and sensor array. Taste sensors used in this experiment include sourness, bitterness, astringency, umami and saltiness. In this experiment, all the wine bottles were opened on the same day, and samples were stored at a constant temperature of 25 °C before measurement. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 15 min, 80 mL grape wine was filtrated, and the supernatant was gained for electronic tongue determination. Each sample was repeated four times, and the last three stable sets of data were retained.

Data analysis

-

All the assays were performed in triplicate for each of grape wine and the experimental data was expressed as mean values. The PCA data were organized by Origin 95. Radar fingerprint chart was organized by Excel. Electronic nose measurement of grape wine sample was performed using Win Muster software (Winmuster1.6.2) for loading analysis. Least significant difference (LSD, defined when P < 0.05) were used to analyze the significant differences among 17 wine samples via SAS (V8.0, the SAS Institute, USA).

-

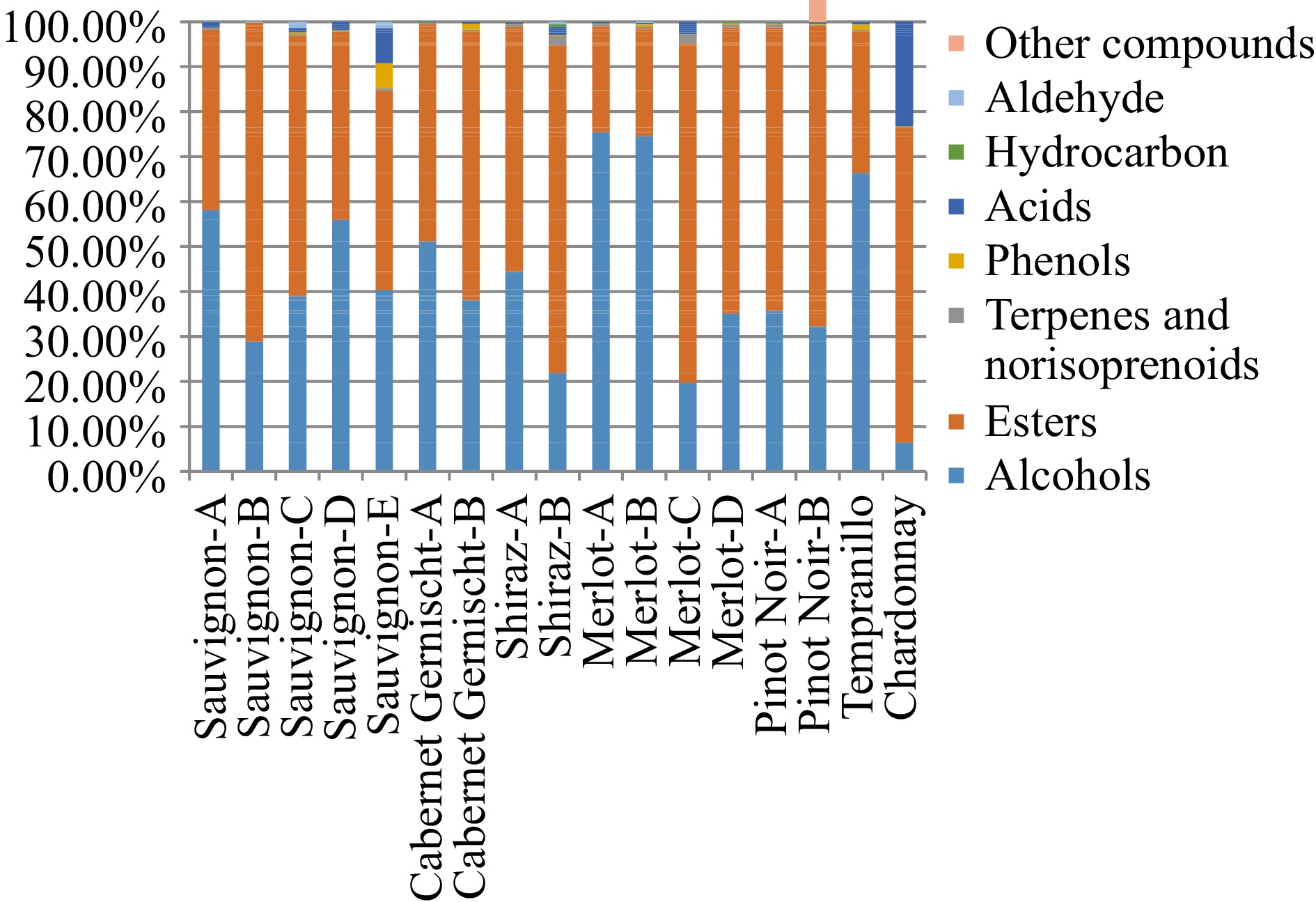

A total of 86 volatile flavor compounds were identified in 17 samples from seven kinds of grape wines using HS-SPME-GC-MS, including 10 alcohols, 44 esters, 14 terpenes and norisoprenoids, eight hydrocarbons, five acids, one aldehyde, two phenols, and two other compounds (Supplemental Table S1). About 46, 41, 45, 45, 59, 16 and 13 kinds of volatile compounds were identified on Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Gernischt, Shiraz, Merlot, Pinot Noir, Tempranillo and Chardonnay, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1, the sum content of esters and alcohols made up the most of total volatile content. Alcohols were the predominant flavor substances in Cabernet Sauvignon-A, Cabernet Sauvignon-D, Cabernet Gernischt-A, Merlot-A, Merlot-B and Tempranillo with relative contents of 58.16%, 55.96%, 51.13%, 75.44%, 74.61% and 66.57%, respectively. However, in Cabernet Sauvignon-B, Cabernet Sauvignon-C, Cabernet Sauvignon-E, Cabernet Gernischt-B, Shiraz-A, Shiraz-B, Merlot-C, Merlot-D, Pinot Noir-A, Pinot Noir-B and Chardonnay, esters were found to be the main volatile compounds. The most abundant volatile compounds of 17 samples were 3-methyl-1-butanol, phenylethyl alcohol, butanedioic acid diethyl ester, hexanoic acid ethyl ester and octanoic acid ethyl ester, decanoic acid, ethyl ester. 3-methyl-1-butanol is major contributor to the alcoholic fraction and it is formed by the deamination and decarboxylation of leucine. 2-Phenylethanol, an alcohol that gives a pleasant rose aroma can be considered as a component of the primary aroma. The esters are the largest class of volatile compounds present in wine. They are responsible for the secondary and the tertiary aroma of wines. The main volatile compounds in Cabernet Sauvignon-A and Cabernet Sauvignon-D were 3-methyl-1-butanol, hexanoic acid ethyl ester (apple, fruity, sweetish notes), butanedioic acid diethyl ester. 3-methyl-1-butanol and octanoic acid ethyl ester (ripe fruits, pear, sweety notes) were found to be the major volatile compounds contributing to the flavor of Cabernet Gernischt-A. Hexanoic acid, 2-methylpropyl ester and 1-Isopropyl-2-methoxy-4-methylbenzene were the two unique flavor compounds of Shiraz-A. 3-methyl-1-butanol accounts for a relatively high proportion in Merlot-A, Merlot-B and Tempranillo and high levels of 3-methyl-1-butanol (smokey and unpleasant aroma) might contribute negatively to the grape wine aroma profile. Terpenoids and norisoprenoids have great benefits for the human body and they contribute to some highly desirable descriptors such as floral and citrus notes[41]. In the present study, 14 different terpenoids and norisoprenoids were identified for the seventeen samples. 6, 5, 5, 6 and 6 kinds of terpenoids and norisoprenoids were identified on Cabernet Sauvignon-A, Shiraz-A, Merlot-C, Pinot Noir-A and Pinot Noir-B, respectively. 1,2-dihydronaphthalene-1,1,6-trimethyl (TDN) which is described as petroleum, kerosene and diesel was generally detected in all samples except Cabernet Sauvignon-B. Among 17 grape wines, the variety of volatile compounds in Pinot Noir was the most abundant. Hydrocarbons in wine result from the waxy components of the grape surface, appear in very small quantities and participate in the varietal aroma but without any special organoleptic significance[42]. Phenolic compounds play a key role in defining the quality of a red wine, because they participate directly in color, the antioxidant properties, astringency and bitterness of the wine[16]. 3-ethylphenol and 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)phenol were detected among the 17 wines. The proportion between the different volatile compounds is fundamental in order to impress a harmonious equilibrium to the grape wine profile. For example, the presence of alcohols in too high concentrations could be a negative feature since they may hide the positive contribution of esters or aldehydes (floral and fruity).

HPLC analysis

-

Phenolic acids also contribute to the taste of grape wines. In this study, eight phenolic acids including gallic acid, protocatechuic acid, vanillic acid, catechin, caffeic acid, syringic acid, p-coumaric acid and ferulic acid were analyzed and the quantitative results were shown in Table 2. In total, the highest concentration of phenolic compounds was observed in Pinot Noir-A (167.743 ± 2.395 mg/L), while the lowest was in Chardonnay (48.321 ± 1.628 mg/L). The most abundant phenols in sixteen red wine samples were gallic acid and catechin. Wine made from Pinot Noir grape variety had the highest concentration of catechin compared to the other sixteen wine samples, which is in accordance with the results published by Krstonosic et al.[43]. Concerning other abundant phenols, protocatechuic acid was detected in a relatively high concentration (8.658−27.230 mg/L) in seventeen wines. The observed differences in the phenolic content could be attributed to many factors, including terroirs, grape maturity, and varietal characteristics, as well as the applied winemaking technology.

Table 2. Phenolic acids in seventeen grape wines using HPLC.

Phenolic acids Contents of phenolic acids (mg/L) Cabernet Sauvignon-A Cabernet Sauvignon-B Cabernet Sauvignon-C Cabernet Sauvignon-D Cabernet Sauvignon-E Cabernet Gernischt-A Cabernet Gernischt-B Shiraz-A Shiraz-B Merlot-A Merlot-B Merlot-C Merlot-D Pinot

Noir-APinot

Noir-BTempranillo Chardonnay gallic acid 22.322 ± 2.408fg 19.224 ± 2.945h 19.187 ± 0.882h 30.553 ± 4.171cd 34.722 ± 0.512b 22.912 ± 0.691f 18.660 ± 1.355h 39.721 ± 1.848a 32.877 ± 0.162bc 23.673 ± 0.179f 27.293 ± 0.031e 28.391 ± 0.055de 31.806 ± 0.626c 41.739 ± 1.206a 15.424 ± 0.126i 19.900 ± 0.039gh 3.108 ±

0.068jprotocatechuic acid 21.171 ± 1.289bc 9.788 ± 1.216kl 12.985 ± 0.209fgh 19.860 ± 2.938cd 10.796 ± 0.168jk 11.607 ± 0.127hijk 14.315 ± 1.597f 10.949 ± 1.008ijk 27.230 ± 1.376a 8.658 ± 0.114l 17.858 ± 0.134e 18.319 ± 0.021de 26.639 ± 0.207a 22.171 ± 0.631b 12.739 ± 0.985fghi 13.551 ± 0.056fg 12.295 ± 0.163ghij vanillic acid 6.851 ±

0.202h8.362 ±

0.201g9.792 ±

0.756f2.150 ±

0.151j4.939 ±

0.042i2.117 ± 0.368j 9.495 ± 1.301f 2.832 ± 0.225j 14.841 ± 0.188d 2.980 ± 0.150j 22.551 ± 0.327a 16.620 ± 0.201c 17.987 ± 1.514b 17.272 ± 0.975bc 9.006 ± 0.515fg 11.034 ± 0.133e 5.999 ± 0.705h catechin 34.540 ± 2.871h 20.991 ± 1.712l 29.309 ±

1.03i33.886 ± 1.693h 55.238 ± 0.983c 45.555 ± 0.632d 24.244 ± 1.062k 46.814 ± 0.439d 40.728 ± 0.448ef 34.660 ± 0.965h 42.315 ± 0.987e 37.839 ± 0.482g 39.583 ± 1.280fg 58.853 ± 0.347b 63.725 ± 1.595a 26.547 ± 0.947j 13.135 ± 0.109m caffeic acid 1.565 ±

0.293i1.498 ±

0.106ij3.313 ±

0.029h9.050 ±

0.149b11.735 ± 0.008a 6.262 ± 0.557d 5.050 ± 0.430f 7.807 ± 0.480c 3.991 ± 0.281g 7.644 ± 0.026c 5.588 ± 0.469e 7.342 ± 0.243c 4.098 ± 0.249g 6.198 ± 0.201d 1.026 ± 0.149j 6.008 ± 0.428de 2.010 ±

0.045isyringic acid 10.954 ± 1.501d 9.369 ± 0.537ef 10.348 ± 1.127de 15.011 ± 0.497b 8.751 ±

0.007f17.211 ± 0.249a 12.294 ± 0.786c 13.370 ± 0.877c 9.908 ± 0.359edf 5.360 ± 0.019g 5.755 ± 0.133g 9.205 ± 0.283ef 8.966 ± 0.623f 14.902 ± 0.713b 3.925 ± 0.372h 5.416 ± 0.070g 6.217 ± 0.683g p-coumaric acid 6.128 ± 0.305cde 4.327 ± 0.495fg 5.560 ±

0.233e7.353 ±

0.480b6.309 ± 0.024cd 6.351 ± 0.657cd 4.311 ± 0.306fg 7.897 ± 0.469b 1.420 ± 0.301h 5.828 ± 0.143de 8.792 ± 0.055a 4.733 ± 0.079f 4.879 ± 0.013f 4.229 ± 0.622fg 6.697 ± 0.630c 3.848 ± 0.087g 0.741 ±

0.042iferulic acid 1.444 ±

0.250f0.643 ±

0.101h0.956 ±

0.078g0.954 ±

0.075g1.023 ± 0.022g 1.616 ± 0.079ef 1.612 ± 0.164ef 1.876 ± 0.131de 1.596 ± 0.035f 3.080 ± 0.177b 1.903 ± 0.172d 2.063 ± 0.054d 2.011 ± 0.030d 2.377 ± 0.171c 0.999 ± 0.070g 2.517 ± 0.191c 4.817 ± 0.347a Total 104.975 ± 3.850g 74.204 ± 5.231j 91.450 ± 2.602i 118.816 ± 0.709e 133.513 ± 0.701bc 113.631 ± 1.378f 89.982 ± 3.098i 131.267 ± 3.470c 132.591 ± 1.132bc 99.539 ± 1.254h 132.055 ± 1.331bc 124.512 ± 0.298d 135.969 ± 1.285b 167.743 ± 2.395a 113.542 ± 2.107f 88.821 ± 1.140i 48.321 ± 1.628k Each value is expressed as mean ± SD (n=3) and data in the same row with different letters are significantly different (P < 0.05). Free amino acids analysis

-

The amino acids can not only provide nitrogen for the growth of microorganisms, but also they can bring nice color for the wine[44]. As one of the essential components of grape wine, amino acids supply diverse tastes which were umami (monosodium glutamate, MSG)-like (including Asp and Glu), bitter (including Val, Met, Ile, Leu, Phe, His and Arg) and sweet (including Thr, Ser, Gly and Ala)[45]. In this study, 17 kinds of free amino acids (FAAs) in seventeen grape wines were detected. The total content of amino acids varied from 144.702 ± 8.589 to 510.153 ± 6.708 mg/L as shown in Table 3. The top five grape wines with the highest total amino acids were Pinot Noir-A, Tempranillo, Cabernet Sauvignon-A, Pinot Noir-B and Merlot-B. There was a significant difference (P < 0.05) in MSG-like amino acids content among Pinot Noir-A, Chardonnay, Cabernet Sauvignon-D, Cabernet Sauvignon-B, Cabernet Gernischt-B and Shiraz-B. However, no notable difference in bitter amino acids was observed among Cabernet Sauvignon-A, Cabernet Sauvignon-D and Cabernet Sauvignon-E. The content of essential amino acids among Merlot-D, Pinot Noir-A and Chardonnay were significantly different from each other. Cabernet Sauvignon-E, Shiraz-A, Merlot-B and Pinot Noir-B had little difference in the content of sweet amino acids. Further, our results revealed that among these amino acids, glutamic acid, proline, lysine, arginine and alanine predominated. Glutamic acid which has the umami taste can improve the taste of grape infusions. Pinot Noir-A had the highest content of total amino acids, taste-active amino acids (MSG-like, bitter and sweet components) and essential amino acids among seventeen grape wines. Since free amino acids are precursors of flavor compounds, the different contents of free amino acids were highly correlated to the complex synthesis of flavor compounds in grape wines. Free amino acids are closely related to the taste of the grape wines, which determines the quality of the grape wines.

Table 3. Comparison of free amino acids (FAAs) in different kinds of grape wines.

FAAs Contents of FAAs (mg/L) Cabernet Sauvignon-A Cabernet Sauvignon-B Cabernet Sauvignon-C Cabernet Sauvignon-D Cabernet Sauvignon-E Cabernet Gernischt-A Cabernet Gernischt-B Shiraz-A Shiraz-B Merlot-A Merlot-B Merlot-C Merlot-D Pinot

Noir-APinot

Noir-BTempranillo Chardonnay Aspartic acid (Asp) 21.525 ±

1.519c13.433 ±

1.031f17.666 ±

0.575d14.921 ±

0.762e25.437 ±

0.502b15.846 ±

1.601e11.094 ±

0.09g15.391 ±

0.05d13.668 ±

0.06f8.076 ±

0.168h22.347 ±

0.339c7.850 ±

0.210h6.347 ±

0.451i33.736 ±

0.464a24.744 ±

0.267b7.291 ±

0.152hi24.332 ±

1.113bThreonine (Thr*) 16.269 ±

1.056c12.063 ±

0.853ef10.578 ±

0.714g11.488 ±

0.611gf13.503 ±

0.262d12.406 ±

0.507ef8.693 ±

1.461h13.749 ±

0.110d9.002 ±

0.039h8.181 ±

0.056h13.022 ±

0.231de5.339 ±

0.144i3.458 ±

0.251j27.163 ±

0.401b13.234 ±

0.121de6.562 ±

0.139i31.053 ±

2.011aSerine (Ser) 16.291 ±

0.906c10.945 ±

0.827g12.117 ±

1.050f10.472 ±

0.498g14.156 ±

0.282d12.004 ±

0.791f8.572 ±

0.105h13.099 ±

0.113e7.701 ±

0.038hi6.924 ±

0.119i13.434 ±

0.189de6.768 ±

0.180i4.393 ±

0.314j22.375 ±

0.321b13.233 ±

0.142de5.119 ±

0.095j37.086 ±

1.283aGlutamic acid (Glu) 49.592 ±

1.962c29.761 ±

1.331i37.523 ±

0.552f33.494 ±

1.637h42.911 ±

0.879d36.752 ±

1.665e29.229 ±

0.262i40.975 ±

0.0918de22.722 ±

0.097j24.139 ±

0.344j35.406 ±

0.557g22.510 ±

0.547j19.312 ±

1.210k82.522 ±

0.901a35.544 ±

0.415g17.984 ±

0.270k78.470 ±

1.532bProline (Pro) 47.364 ±

1.523c44.537 ±

1.459d41.971 ±

1.562e36.592 ±

0.454f12.211 ±

0.253j40.114 ±

1.500e36.604 ±

0.997f40.966 ±

0.212e35.376 ±

1.341fg33.374 ±

0.677g45.784 ±

2.334cd37.380 ±

1.495f22.142 ±

0.251i65.491 ±

0.840a33.837 ±

1.868g30.493 ±

0.151h59.197 ±

1.503bGlycine (Gly) 23.421 ±

2.099b14.103 ±

0.939f16.887 ±

0.242de16.110 ±

0.835e18.429 ±

0.352c15.579 ±

1.300e13.557 ±

0.137f16.509 ±

0.188e12.292 ±

0.054g10.829 ±

0.127h18.142 ±

0.337cd10.299 ±

0.289h10.842 ±

0.771h32.777 ±

0.752a18.313 ±

0.188c7.6452 ±

0.142i18.943 ±

0.631cAlanine (Ala) 39.205 ±

1.851bc26.972 ±

1.254g30.702 ±

1.026e35.004 ±

1.763d38.996 ±

1.659bc34.357 ±

1.659d28.894 ±

0.451f38.139 ±

0.197c27.647 ±

0.134fg22.450 ±

0.235h40.208 ±

1.078b20.594 ±

0.587i18.195 ±

1.326j75.277 ±

0.950a37.903 ±

0.413c16.628 ±

0.304j16.820 ±

0.008jCysteine (Cys) 5.540 ±

0.104cd1.783 ±

0.082g1.354 ±

0.095h2.178 ±

0.084f1.465 ±

0.021hg5.280 ±

0.511ed1.401 ±

0.084hg5.873 ±

0.100c1.281 ±

0.025h5.126 ±

0.084e1.352 ±

0.148h1.131 ±

0.061h1.132 ±

0.62h7.094 ±

0.151b1.467 ±

0.039hg5.095 ±

0.041e9.678 ±

0.677aValine (Val*) 17.734 ±

0.779b11.333 ±

0.920g10.746 ±

0.591g11.000 ±

0.547g12.718 ±

0.219ef12.414 ±

0.624f8.266 ±

0.139h14.721 ±

0.071c7.854 ±

0.042h8.522 ±

0.194h13.401 ±

0.334de6.770 ±

0.183i4.781 ±

0.329j27.156 ±

0.393a13.798 ±

0.141d8.534 ±

0.065h17.712 ±

0.611bMethionine (Met*) 8.801 ±

0.302b4.274 ±

0.253f3.833 ±

0.311g4.509 ±

0.208ef5.550 ±

0.272d2.976 ±

0.332hi3.393 ±

0.090h7.962 ±

0.039c2.733 ±

0.011ij2.167 ±

0.603k4.914 ±

0.144e2.118 ±

0.055k1.543 ±

0.11l11.846 ±

0.131a4.765 ±

0.056e2.429 ±

0.026jk5.465 ±

0.466dIsoleucine (Ile*) 7.964 ±

0.353b5.198 ±

0.235hg5.155 ±

0.258hg4.997 ±

0.249hg6.017 ±

0.111de5.337 ±

0.677fg3.611 ±

0.044i5.623 ±

0.045ef3.388 ±

0.026i1.805 ±

0.066k6.385 ±

0.113cd2.878 ±

0.081j1.708 ±

0.118k9.591 ±

0.158a6.544 ±

0.083c1.776 ±

0.003k4.836 ±

0.329hLeucine (Leu*) 17.252 ±

0.553d16.345 ±

0.735e14.193 ±

0.407g15.124 ±

0.783f21.805 ±

0.425b11.825 ±

0.750h10.729 ±

0.104i14.612 ±

0.025fg11.344 ±

0.057hi5.575 ±

0.073k18.994 ±

0.339c8.527 ±

0.262j5.383 ±

0.400k25.117 ±

0.451a17.209 ±

0.215d5.225 ±

0.162k17.531 ±

0.642dTyrosine (Tyr) ND 13.138 ±

0.663d12.427 ±

0.839e10.907 ±

0.445g9.98 ±

0.156hND 16.776 ±

0.129c12.025 ±

0.019e6.011 ±

0.012k7.871 ±

0.062i23.243 ±

0.342b6.382 ±

0.130k7.041 ±

0.463jND 10.059 ±

0.06g4.621 ±

0.338l28.734 ±

0.508aPhenylalanine (Phe*) 17.956 ±

0.721d15.889 ±

0.609f14.612 ±

0.535g16.983 ±

0.871e23.974 ±

0.416c14.005 ±

0.601g11.978 ±

0.104h17.690 ±

0.060de12.123 ±

0.083h10.386 ±

0.083i18.076 ±

0.293d10.289 ±

0.263i5.070 ±

0.367j29.293 ±

0.341b18.266 ±

0.18410.089 ±

0.107i33.473 ±

1.008aLysine (Lys*) 25.432 ±

0.979b17.212 ±

0680f18.807 ±

0.74919.639 ±

0.963e26.293 ±

0.475b21.102 ±

0.684d14.359 ±

0.082h23.706 ±

0.062c15.486 ±

0.053g14.371 ±

0.189h23.719 ±

0.378c11.691 ±

0.339i9.576 ±

0.613j35.700 ±

0.679a21.965 ±

0.276d12.052 ±

0.061i25.346 ±

0.916bHistidine (His) 3.439 ±

0.038j3.164 ±

0.157j3.604 ±

0.145j6.410 ±

0.276g11.158 ±

0.181b1.513 ±

0.130l2.186 ±

0.10k10.079 ±

0.033c5.502 ±

0.022h6.711 ±

0.060fg4.287 ±

0.052i7.488 ±

0.195ed7.033 ±

0.423ef4.784 ±

0.137i7.797 ±

0.091d3.409 ±

0.076j27.230 ±

1.189aArginine (Arg) 21.602 ±

1.500f23.530 ±

0.928e14.266 ±

0.564h34.958 ±

1.719b12.218 ±

0.282j23.194 ±

1.510e31.221 ±

0.515c17.041 ±

0.141h25.002 ±

0.318d23.730 ±

0.317de17.294 ±

0.242h10.844 ±

0.304j16.746 ±

1.144h20.205 ±

0.315g46.065 ±

0.512a13.638 ±

0.313i16.389 ±

0.768hEssential amino acids 111.389 ±

3.63c82.317 ±

3.414ef77.924 ±

3.549f83.739 ±

1.636e109.860 ±

1.636c80.0643 ±

3.377ef61.030 ±

2.024g98.063 ±

0.178d61.931 ±

0.305g51.007 ±

0.474h98.511 ±

1.831d47.612 ±

1.328h31.519 ±

2.177i165.887 ±

2.473a95.782 ±

1.076d46.668 ±

0.543h135.415 ±

5.299bMSG-like 71.118 ±

3.171c43.195 ±

2.346h55.189 ±

1.059ef48.415 ±

2.400g68.348 ±

1.382c52.597 ±

3.263f40.323 ±

0.356i56.365 ±

0.142e36.390 ±

0.159j32.216 ±

0.492k57.753 ±

0.896de30.363 ±

0.757k25.659 ±

1.661l116.256 ±

1.241a60.288 ±

0.682d25.275 ±

0.420l102.806 ±

2.626bBitter 94.728 ±

3.420d80.185 ±

3.159f66.410 ±

3.045h93.981 ±

4.683d93.439 ±

1.361d71.264 ±

4.026g71.264 ±

4.026g87.728 ±

0.060e67.946 ±

0.342gh58.895 ±

0.430i83.351 ±

1.516f48.914 ±

1.343j42.264 ±

2.879k128.010 ±

1.877a114.444 ±

1.282c45.101 ±

0.744jk122.636 ±

3.935bSweet 95.186 ±

5.489c64.083 ±

3.794f70.283 ±

1.930e73.073 ±

3.707e85.084 ±

1.674d74.346 ±

4.020e59.716 ±

2.155fg81.496 ±

0.587d56.643 ±

0.264g48.384 ±

0.521h84.384 ±

1.834d43.001 ±

1.200i36.888 ±

2.661j157.592 ±

2.405a82.684 ±

0.863d35.961 ±

0.672j103.903 ±

3.889bTotal 339.369 ±

13.086c264.133 ±

8.793h266.442 ±

6.253h284.785 ±

11.827g296.221 ±

5.321fg264.703 ±

12.407h240.567 ±

4.807i308.159 ±

0.947ef219.133 ±

0.527j200.237 ±

1.429k320.009 ±

7.448de178.862 ±

5.324l144.702 ±

8.589n510.153 ±

6.708a324.744 ±

1.333d158.597 ±

2.238m452.296 ±

13.074bEach value is expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3) and data in the same row with different letters are significantly different (P < 0.05). a ND: not detected. * Means essential amino acids. E-nose analysis

-

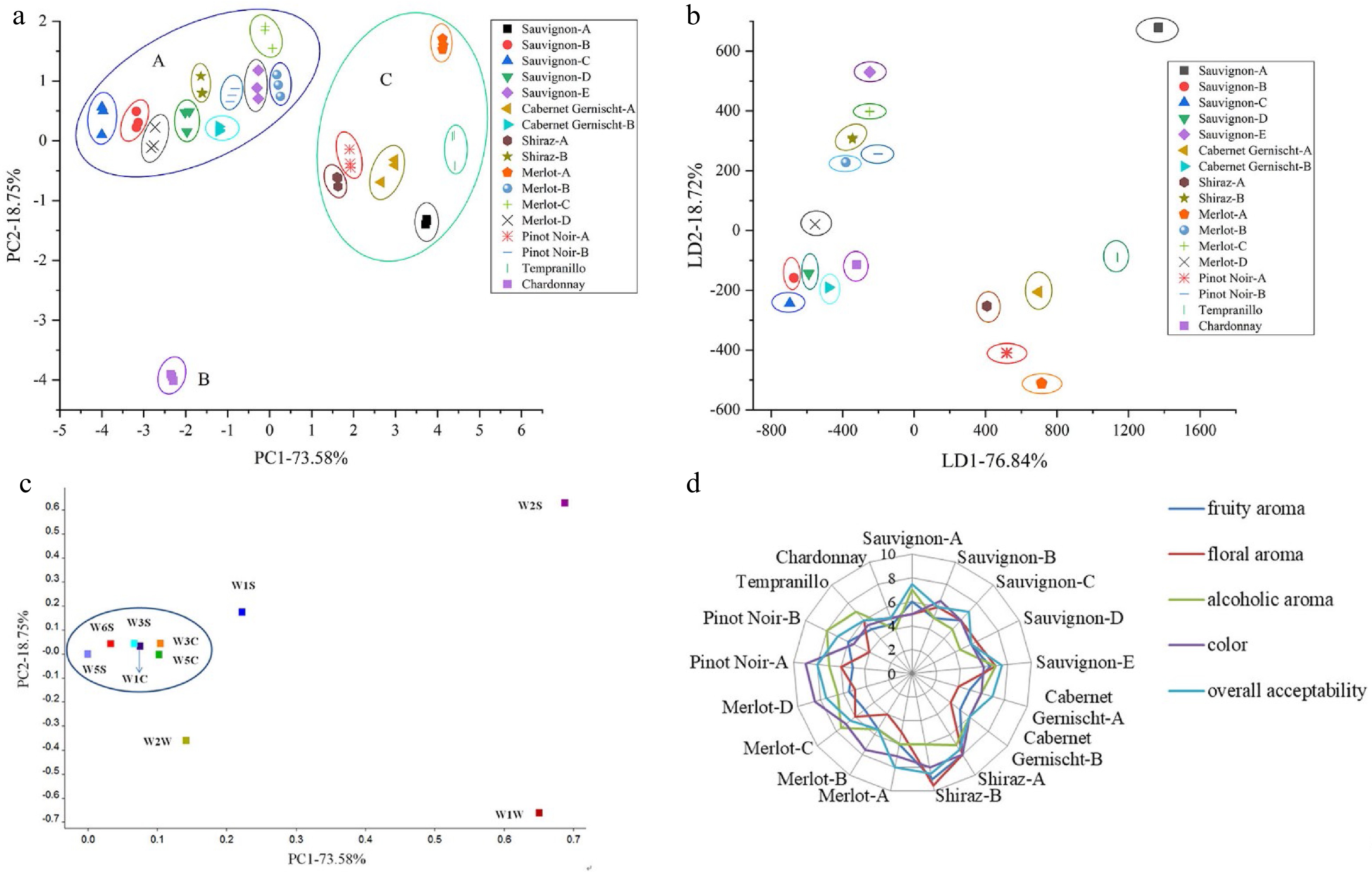

The E-nose was a good method to analyze aroma, as it could offer a fast and non-destructive method to sense volatile substances[46]. PCA was a statistical tool that explained the differentiation between samples as well as the relationship between the objects[47−49]. A clear separation of the samples into 17 groups was found according to the PCA plot of the different grape varieties as shown in Fig. 2a. The principal components PC1 and PC2 represented 73.58% and 18.75% of the total variance, respectively, with the cumulative contribution rate accounting for 92.33%. In general, when the accumulated contribution of certain principal compounds (PCs) is over 85%, the PCs can represent the original data. The clusters of the data were divided into three groups labeled A, B and C. Group A was composed of ten subclusters without being overlapped. However, they were closer to each other, indicating that similar volatile ingredients existing in these ten samples (Cabernet Sauvignon-B, Cabernet Sauvignon-C, Cabernet Sauvignon-D, Cabernet Sauvignon-E, Merlot-B, Merlot-C, Merlot-D, Cabernet Gernischt-B, Shiraz-B and Pinot Noir-B). Related to HS-SPME-GC-MS analysis, the difference in the aroma profile among Chardonnay and other wines, Chardonnay located in the left-bottom area labeled B and clearly isolated from the other 16 red wines in PCA plot of E-nose. Group C was made up of six wine samples including Cabernet Sauvignon-A, Shiraz-A, Pinot Noir-A, Cabernet Gernischt-A, Merlot-A, and Tempranillo, clearly isolated from each other. All of them generate special aroma because of their unique fermentation process and raw materials. E-nose is sensitive for obtaining smell information, and slight changes of flavor could result in different sensors response. The results illustrate that this non-destructive method by E-nose is an effective assay for grape wine discrimination.

Figure 2.

(a) PCA plot, (b) LDA plot, (c) loading analysis of E-nose for 17 grape wines and (d) graph of sensory scores of the 17 grape wines.

Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) is frequently used for classification in food field and its main aim is to find the linear combinations of noted attributes that can well separate two or more than two classes of objects[50]. The classification results of the 17 grape wines on the coordinates based on first linear discriminant (LD1) and second linear discriminant (LD2) represented 76.84% and 18.72% of the total variance, respectively, with the discriminant accuracy accounting for 95.56% are shown in Fig. 2b. The results indicate that the PEN 3 E-nose with LDA is an effective instrument to distinguish the 17 grape wines via their odors.

Loading analysis is useful to check for the influence of a sensor on the distribution of data sets. The loading factor associated to PC1 and PC2 for each sensor is represented in Fig. 2c. The points in the plot represent the sensors used in the experiment. The sensor with loading parameters close to zero for a particular principal component has a low contribution to the total response of the array, whereas high values indicates a discriminating sensor[51]. It is shown that sensors W2S and W1W have a higher influence in the current pattern file while sensors W1S and W2W have relatively low influence. The detectable compounds by sensors W2S and W1W were alcohols and sulfur-containing organics. Sensors W1C, W3S, W5C, W3C, W5S and W6S have closer influence so that they might be represented by one of the group member and this group has a minor influence in the current pattern file.

Fifty mL grape wine was put into a beaker of 250 mL volume, and they were randomly offered to panelists, the aroma descriptors of samples were recorded by panelists. Panelists agreed that the aroma of grape wine samples could be described using five attributes: fruity aroma, floral aroma, alcoholic aroma, color, and overall acceptability. The intensities of the aroma attributes were scored using a scale from 0 to 10, the higher scores, the stronger intensities. Each sample was evaluated three times by each panelist. Data were expressed as mean. A trained panel quantitated the intensity of the aroma attributes of tea samples were evaluated by ten panelists (six females and four males), with aged between 20 and 30 years old. Panelists were trained by a series of important grape wine aroma compounds.

The scores of human aroma sensory evaluation analysis are plotted on the radar chart and shown in Fig. 2d. The result analysis demonstrated that fruity aroma, alcoholic aroma and overall acceptability showed significant differences among Chardonnay and other 16 kinds of red wines in the sensory evaluation scores. This is consistent with the results analyzed by E-nose. Shiraz-B exhibited higher level of floral aroma and fruity aroma which may be related to high relative content of higher alcohols and esters detected by HS-SPME-GC-MS. In addition, Pinot Noir-A and Merlot-D have beautiful color, which perhaps due to their relatively high phenolic contents detected by HPLC.

E-tongue analysis

-

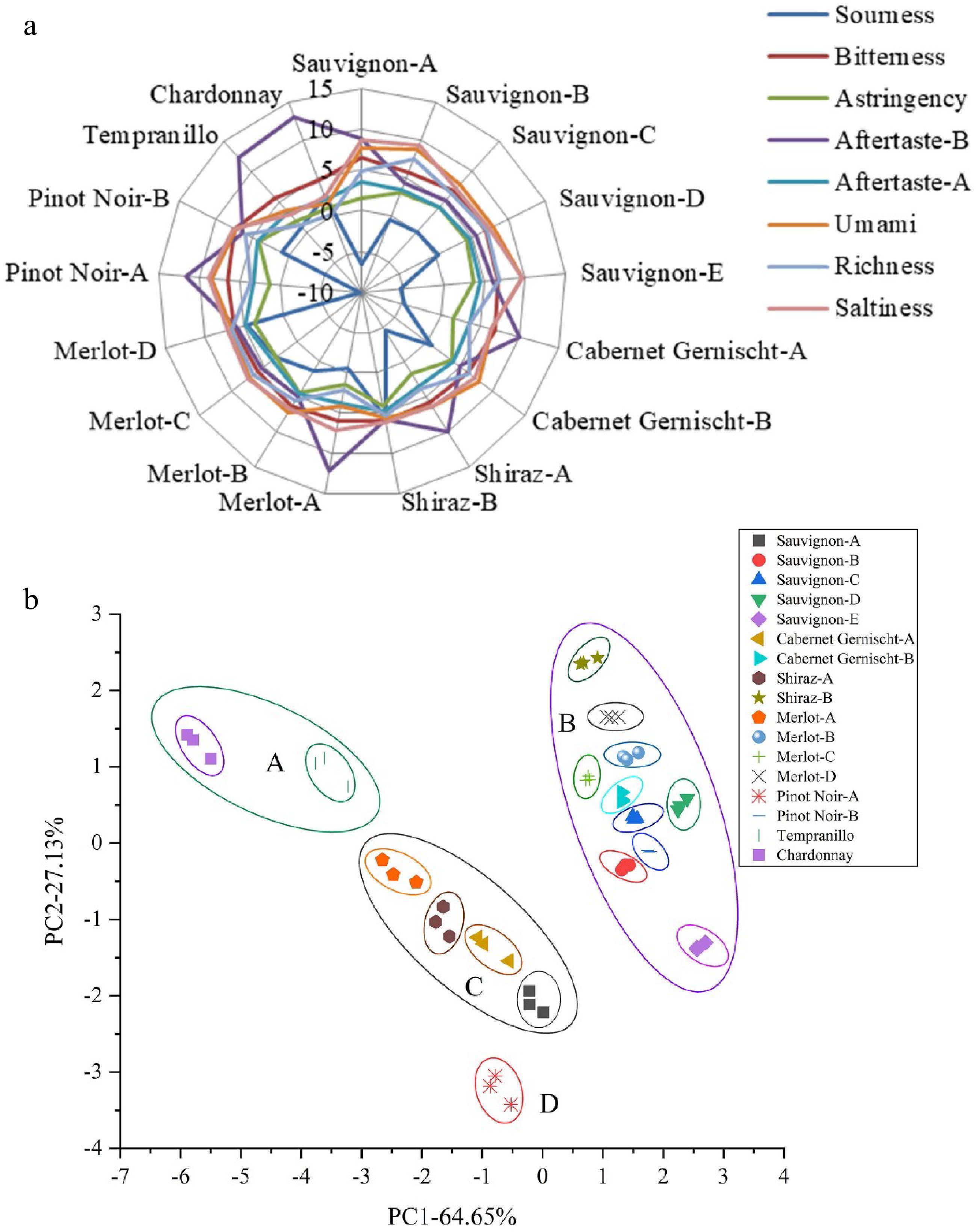

The radar fingerprint chart of E-tongue with different grape varieties was presented in Fig. 3a. The mainly typical taste of grape wine includes astringency and sourness. Significant difference (P < 0.05) was observed in aftertaste-B and sour taste. However, there was a minor difference on the flavor from bitterness, astringency, aftertaste-A richness and umami among 17 grape wines. Further, there was a great correlation between the E-tongue and the human sensory evaluation score[52]. The values of saltiness and richness of Tempranillo and Chardonnay were lower than 15 other grape wines. Astringency taste intensity based on the E-tongue measurement ranged from 1.147 ± 0.045 to 4.400 ± 0.046. The bitterness and astringency of grape wines are mainly correlated to the phenol profile[16, 53]. Pinot Noir-A exhibited the highest sourness intensity with a score of −9.733 ± 0.207. Cabernet Sauvignon-E with the highest umami taste levels also appeared to have the highest saltiness scores. It can therefore be concluded that E-tongue could be a rapid method for taste evaluation in wineries. Consumers can easily choose their preferred grape wines according to the satisfactory taste results offered by E- tongue.

Figure 3.

(a) Radar fingerprint chart of the sensory score, (b) PCA plot of E-tongue data for 17 grape wines.

For variable reduction and separation into classed, PCA was used applied[54]. PCA of non-volatile compounds of 17 samples from seven kinds of grape varieties were presented in Fig. 3b. It was observed that variance contribution rates of PC1 and PC2 were 64.65% and 27.13%, respectively. The accumulative variance contribution rate of the first two PCs was 91.78% (> 85%), which were considered most information to represent the entire samples. In the PCA plot, a better separation effect of 17 grape wines was shown. Tempranillo, Chardonnay, Shiraz-B, Cabernet Sauvignon-E and Pinot Noir-A were clearly separated from other wines. Shiraz-A, Merlot-A, Cabernet Gernischt-A and Cabernet Sauvignon-A were slightly clustered in the centre of the PCA plot. A group comprised of Cabernet Sauvignon-B, Cabernet Sauvignon-C, Cabernet Sauvignon-D, Pinot Noir-B, Merlot-B, Merlot-C, Merlot-D and Cabernet Gernischt-B was located close together, all eight samples had positive score values at PC1. For E-tongue results, the PCA was able to distinguish the 17 wines from seven grape types completely.

-

In this study, the volatile and non-volatile flavor components of grape wines were analyzed by HS-SPME-GC-MS, E-nose, E-tongue, HPLC, and automatic amino acids analyzer techniques. The phenolic substances detected by HPLC are related to the color of the wine and the content of amino acids and phenols affect the taste of the wine, such as bitterness and astringency detected by E-tongue. Meanwhile, the combined use of HS-SPME-GC-MS and electronic nose technology analyzes the volatile flavor of 17 wines. The floral aroma and fruity aroma of the wine are closely related to alcohols and esters. Pinot Noir-A had the highest content of bitter amino acids, phenols and it was clearly separated from other wines in the PCA plot of E-tongue. The flavor and taste of Chardonnay showed great significance compared to 16 other kinds of red wines. Shiraz-B exhibited higher scores of floral aroma and fruity aroma in sensory evaluation, which may be related to its relative amount of volatile aroma substance. A total of 86 volatile compounds were identified among the 17 samples from seven kinds of wine samples. Alcohols and esters were the main flavor substances. The results clearly show that it is possible to classify grape wines from seven varieties by using E-nose and E-tongue. Sensors W2S and W1W in the E-nose for wines have a higher influence in the current pattern file. In addition, the PCA results of E-nose and E-tongue were obtained with the cumulative contribution rate accounting for 92.33% and 91.78%, respectively. Additionally, the content of free amino acids especially the taste-active amino acids, exhibited significant difference (P < 0.05). Gallic acid and catechin made up a large percentage of the grape wines. This study highlighted the usefulness of combining aroma and taste analysis techniques of grape wines, which could effectively instruct consumers to choose their preferred wines. Meanwhile, this research also provided some efficient methods to monitor grape wine quality in the actual process of industrialization. The beverage industry can certainly follow the protocols and parameters presented in this work in order to make use and apply the techniques immediately.

The work was financially supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (KJQN201944).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplemental Table S1 Relative contents of volatile compounds of grape wines from different varieties using HS-SPME-GC-MS.

- Copyright: © 2023 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Fan X, Pan L, Chen R. 2023. Characterization of flavor frame in grape wines detected by HS-SPME-GC-MS coupled with HPLC, electronic nose, and electronic tongue. Food Materials Research 3:9 doi: 10.48130/FMR-2023-0009

Characterization of flavor frame in grape wines detected by HS-SPME-GC-MS coupled with HPLC, electronic nose, and electronic tongue

- Received: 28 March 2023

- Accepted: 05 May 2023

- Published online: 30 May 2023

Abstract: To analyze the flavor components in 17 commercially available wine samples from seven grape varieties (Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Gernischt, Shiraz, Merlot, Pinot Noir, Tempranillo and Chardonnay), comprehensive flavor characterization, volatile and non-volatile compounds of grape wines were evaluated by headspace solid phase micro-extraction (HS-SPME) coupled with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), electronic nose (E-nose), electronic tongue (E-tongue), high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and automatic amino acids analyzer. According to GC-MS analysis, a total of 86 volatile compounds were identified, mainly including alcohols, esters, phenols, terpenes and norisoprenoids. Results showed that significant differences of contents of free amino acids and radar fingerprint chart of E-tongue technology were recorded for the 17 grape wines. Moreover, principal component analysis (PCA) of E-nose and E-tongue were used to distinguish the different grape wines effectively, with the cumulative contribution rate accounting for 92.33% and 91.78%, respectively. The results prove that sensors W2S and W1W in the E-nose for wines have a higher influence in the current pattern file. The most abundant phenol in 17 wine samples is catechin. The differences in species and contents of volatile and non-volatile substances give the unique flavor of different grape wines. The results demonstrated that the above mentioned equipment are useful for in-depth grape wine flavor analysis.

-

Key words:

- Grape wines /

- Flavor /

- HS-SPME-GC-MS /

- E-nose /

- E-tongue /

- HPLC