-

Sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) is an important source of sugar and renewable biofuel for many tropical and subtropical parts of the world[1]. Even though it has a high potential yield, maintaining sugarcane production is difficult because recurring losses are incurred from biotic and abiotic stresses. Abiotic stresses like drought, salinity, heat, and changing environmental conditions have a great impact on the growth, yield, juice quality, and productivity of the crop[2]. The majority of the sugarcane species are very sensitive to these stressors[3]. Sugarcane is highly sensitive to drought, especially during critical growth stages like stalk elongation, germination, and grand growth phases, where water demand is at its peak. Drought during these periods leads to significant reductions in yield, stalk length, plant height, and overall cane and sugar output[4]. Drought stress can cause up to a 33% reduction in yield, negatively affect juice quality, and reduce recoverable sugar per ton of cane[5]. Similarly, sugarcane is also affected by waterlogging conditions. A one-inch increase in surplus water causes the water table to rise, which negatively impacts stalk weight and plant population during the active growth period, and reduces output by around one tonne per acre[6]. Sugarcane is known for being tolerant under flooding and high water tables[7]. According to reports, well-established cane can withstand flooding for a few months, while less-established cane seems to be far more susceptible[6]. According to earlier research, the water table 50 cm or closer to the soil surface causes sugarcane loss of 0.5 t ha–1 for each day[8]. For floods at 7–9 MAP, Gomathi et al.[9] reported yield losses of 5%–30%. Due to inadequate nutrition and water uptake, flooding for 15–60 d during the grand growth phase reduced sugarcane production by roughly 5%–30%[9], whereas three months of flooding reduced the yield by 18%–37% in plant cane, and 61%–63% in the second ratoon[10]. Additionally, Worasant[11] found a 14%–50% decrease in sugarcane output. Excess water leads to poor root aeration, reduced nutrient uptake, increased susceptibility to diseases, and ultimately, yield decline[12,13]. In general, the genotypes, ambient conditions, growth stages, and length of stress all affect how much harm floods cause to sugarcane[14,9].

Plants have developed several mechanisms to maintain growth and productivity during environmental stress, one of which is the induction of phytohormones—tiny chemical messengers that control plant growth, development, and metabolism[15]. Phytohormones are key mediators of plant reactions to water stress. Drought modifies the endogenous contents of major phytohormones, such as auxins, gibberellins (GAs), jasmonic acid (JA), abscisic acid (ABA), salicylic acid (SA), ethylene (ET), and cytokinins (CKs). They are synthesized in minute amounts, yet these hormones control vital cellular processes and allow signal transmission in plants[16]. Under abiotic stress, they integrate intricate signal transduction cascades to regulate plant responses to both internal and external stresses[17]. Notably, ABA levels naturally rise during water scarcity, helping protect plants from desiccation[18]. Given their pivotal role, exogenous application of phytohormones is emerging as a promising strategy to improve stress tolerance in crops. However, limited studies are available on this approach in sugarcane, particularly under drought and waterlogging conditions. This review will help understand the role and impact of exogenous phytohormone application in enhancing sugarcane resilience under drought and waterlogging conditions.

-

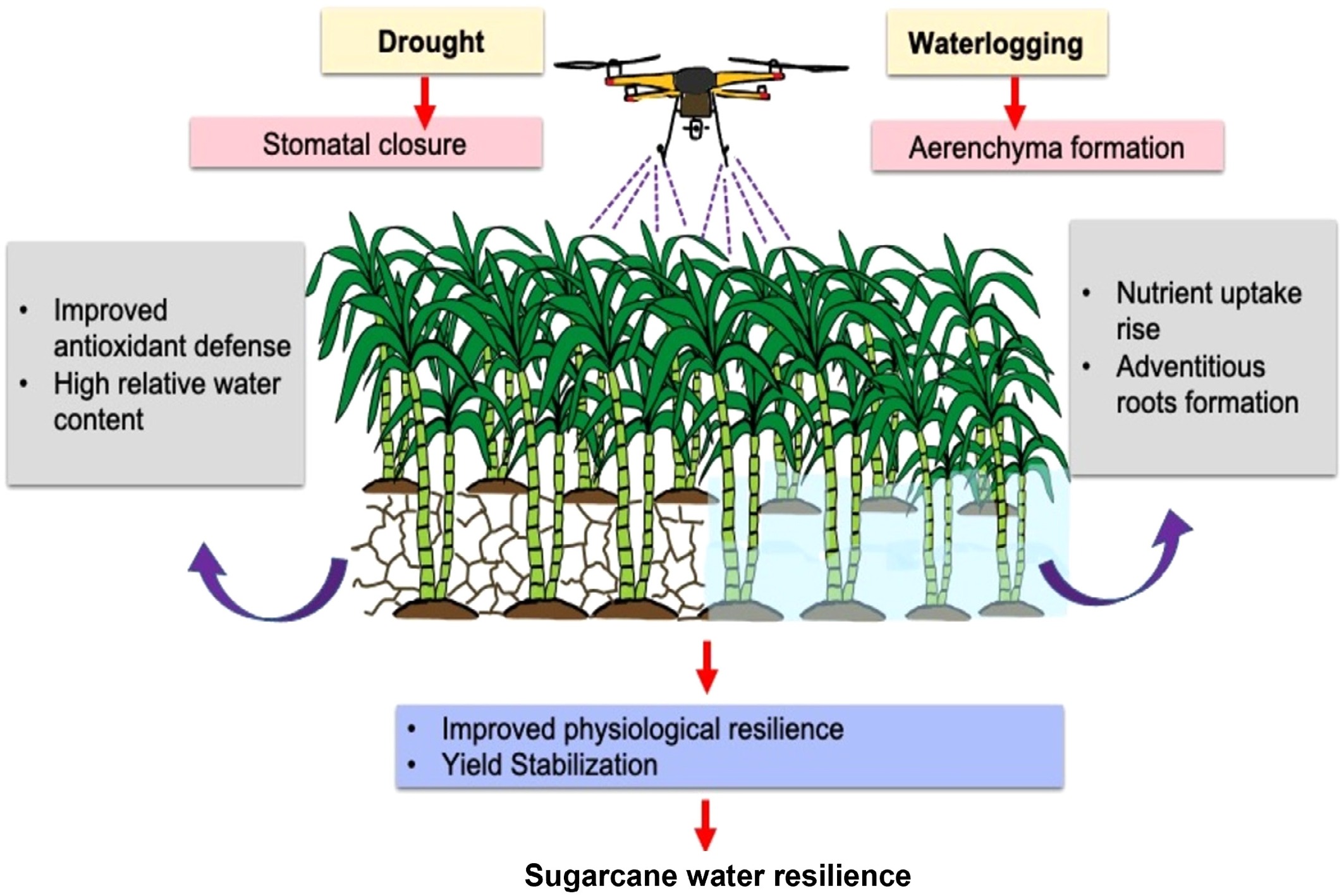

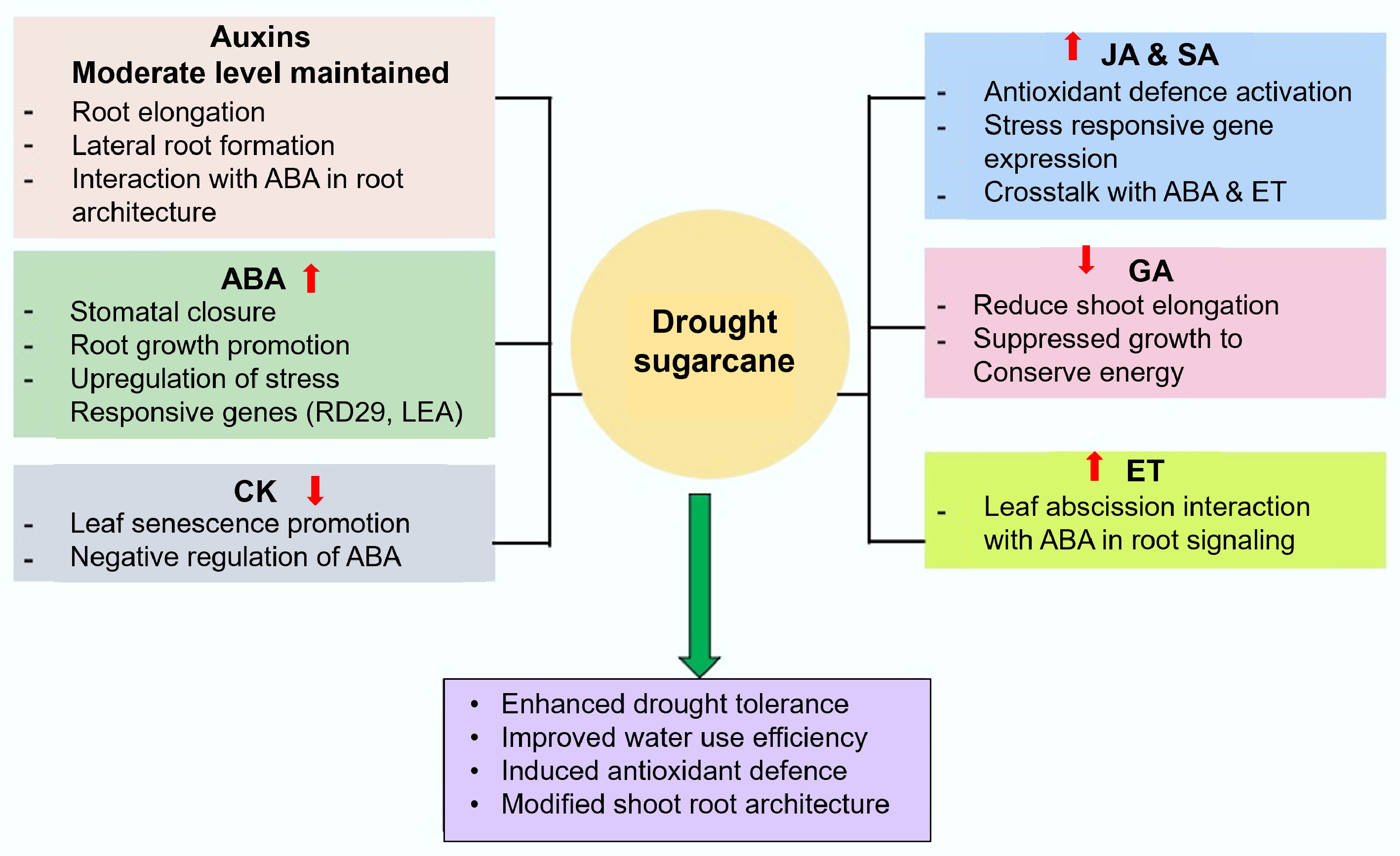

Phytohormones are key regulators in sugarcane's adaptation to water stress, coordinating physiological, molecular, and biochemical responses to maintain growth under stress (Fig. 1). Various hormones, such as ABA, CK, SA, JA, and GA, undergo altered biosynthesis, accumulation, and transport during drought[19]. Rodrigues et al.[20] observed differential gene expression linked to hormone metabolism, stress signalling, and photosynthesis under drought. ABA synthesis, primarily in roots but also in leaves, is triggered by drought. It then translocates throughout the plant, modulating stomatal behaviour, ion channels, and stress-responsive gene expression[21]. ABA enhances antioxidant activity[22], and its accumulation correlates with reduced transpiration and stomatal conductance during prolonged drought[23]. ABA-mediated responses involve signalling pathways with secondary messengers and mineral ions[24−26]. SoNCED, a gene that codes for 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase, catalyzes a central step in ABA biosynthesis and is induced by drought[27]. SoDip22, a sucrose metabolism-related protein, assists in regulating water status in the bundle sheath cells[28]. Indole acetic acid (IAA) regulates growth processes such as apical dominance, cell elongation, and root branching, and is involved in stress adaptation[29]. Elevated levels of IAA and ABA under drought have been reported in sugarcane[23]. Although generally linked with pathogen defence, SA also plays a role in drought tolerance through the modulation of stress-related proteins[30].

-

The balance of multiple phytohormones is fundamental to regulating plant physiological metabolism, growth, and development. Endogenous hormones orchestrate the entire plant life cycle[31−33]. Through complex signalling networks, plants adjust hormone synthesis and transport to respond to environmental stresses, including waterlogging. In this context, hormones serve as vital endogenous cues contributing to stress adaptation[34−36]. Similar phytohormones are also involved in sugarcane adaptation to waterlogging conditions (Fig. 2). ABA plays a central role by regulating stomatal function through modulation of guard cell density, thereby influencing plant water potential. It also promotes the formation of root aerenchyma under waterlogged conditions[37,38]. IAA is essential for plant growth and development[39,40]. GAs influence cell size and proliferation, thereby governing multiple growth and developmental processes[41]. SA, a key phenolic compound, enhances plant resilience by activating antioxidant systems and upregulating stress-responsive genes[42−44]. Under waterlogging, SA acts as a signalling molecule that induces physiological adjustments. Although JA is well-known for its role in abiotic stress responses, its specific involvement in waterlogging tolerance remains less explored[33,45−47]. The JA–ethylene (ET) interaction plays a critical role in root development and aerenchyma formation under waterlogged conditions. Notably, foliar application of methyl jasmonate has been shown to elevate ethylene levels, which in turn enhances tolerance to waterlogging stress[48].

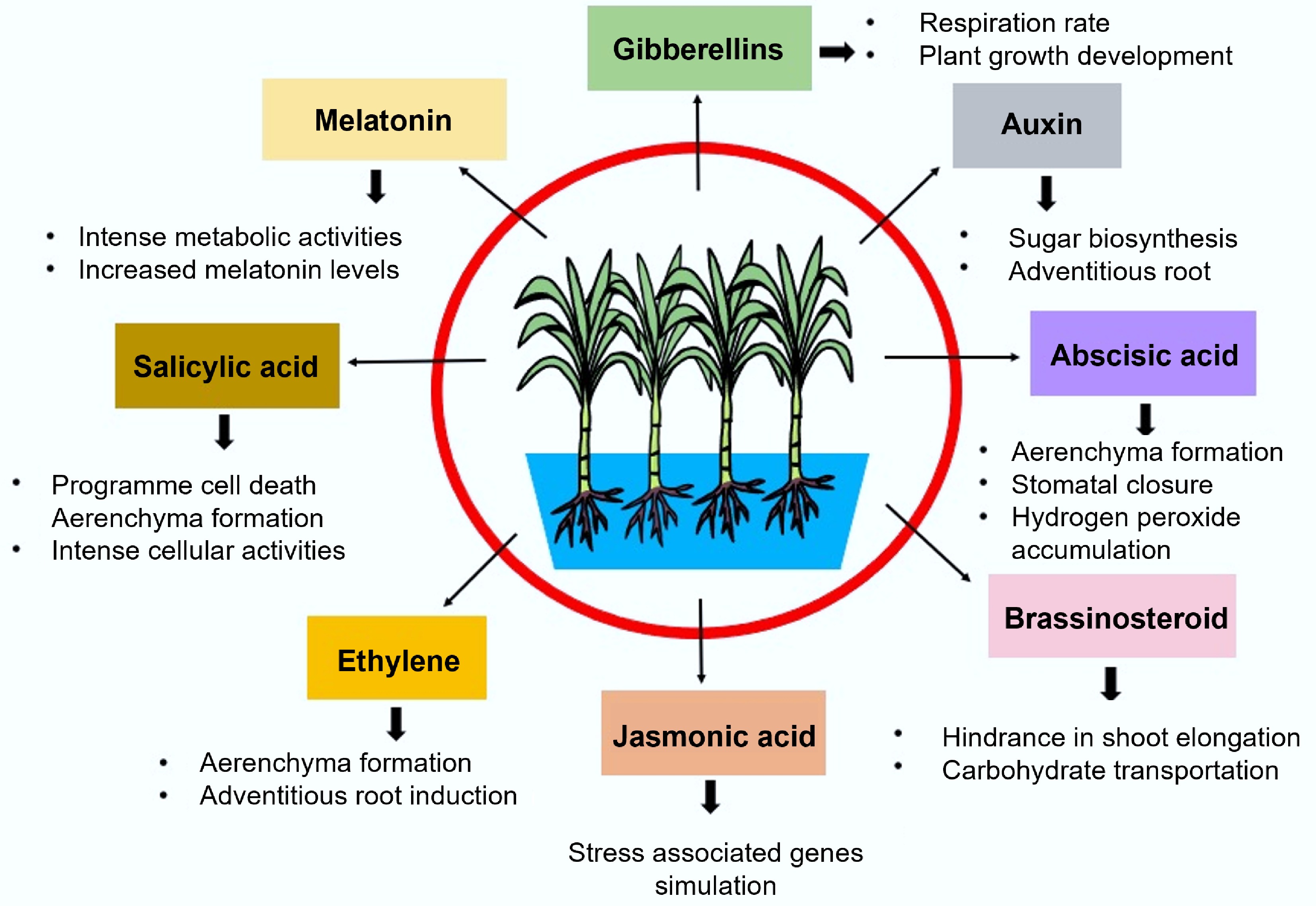

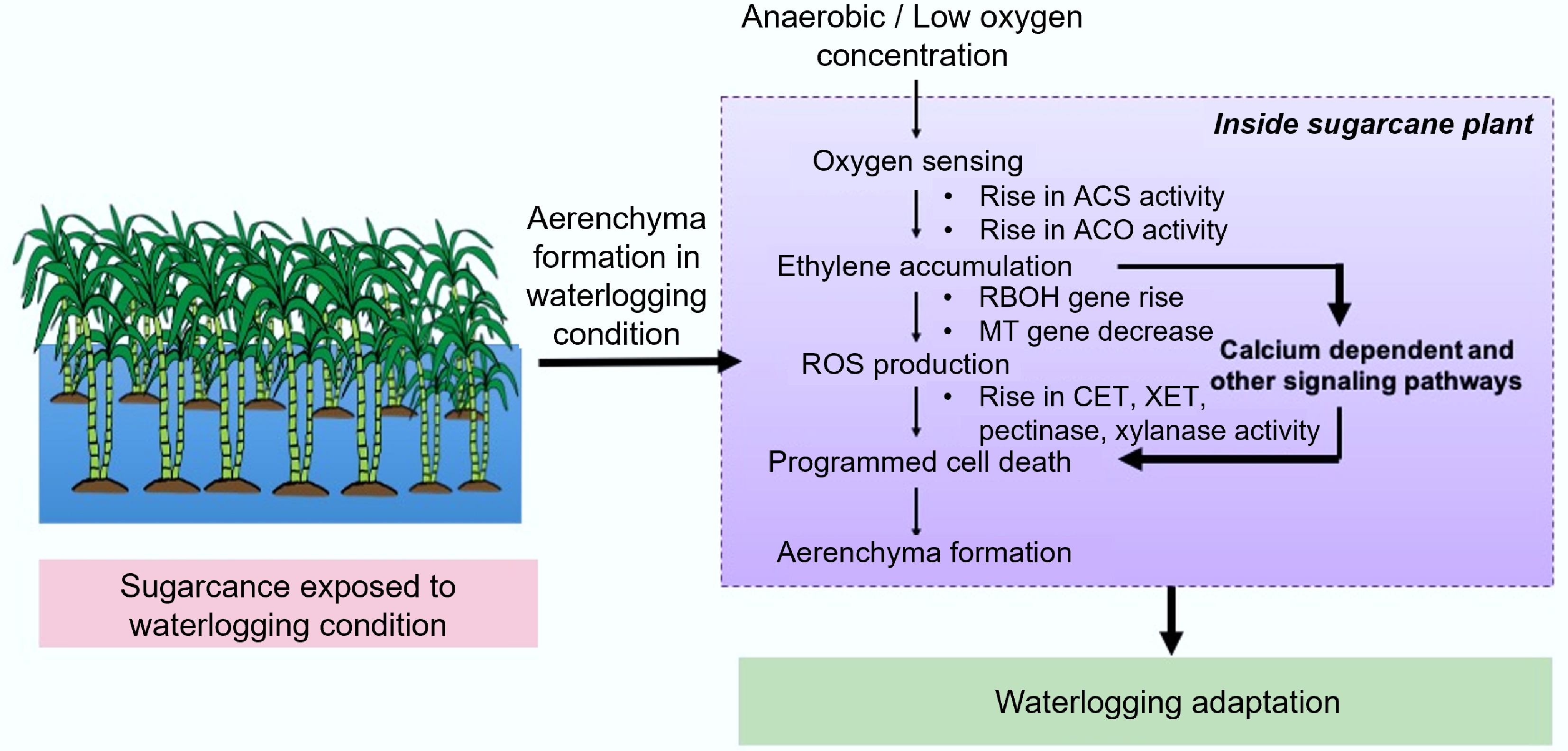

The ET hormone plays a critical role in sugarcane adaptation to waterlogging stress. ET's contribution to adventitious root and aerenchyma formation has been observed across several crops, including sugarcane[49]. A key physiological and morphological response of plants to floods or waterlogging is the production of aerenchyma. It is known to improve internal oxygen diffusion from the aerial sections to the submerged roots, enabling the roots to continue their aerobic respiration[50]. Root porosity is increased above normal levels by intercellular spaces as a result of aerenchyma development[51]. Tolerant genotypes' increased root porosity in response to waterlogging stress may be an adaptation to anaerobic or hypoxic environments[52]. ET production, triggered early during waterlogging, enhances auxin transport to submerged tissues. In turn, auxin accumulation can stimulate ET biosynthesis, reinforcing auxin movement. This feedback loop promotes cell division and aerenchyma formation in roots[53]. Furthermore, Tavares et al.[53] also suggested that the balance between hormones was equally crucial in aerenchyma development under waterlogging conditions. This coupling of hormones may be mediated by the regulation of specific genes involved in cell growth. Additionally, the sugarcane response to ethylene was largely influenced by the inherent capacity for aerenchyma formation rather than the amount of the hormone. Gomathi et al.[9] further demonstrated that under waterlogged conditions, sugarcane forms aerial roots, which maintain higher root activity and ET concentrations. This elevated ET level enhances the sensitivity of tissues involved in adventitious root formation, thus promoting aerenchyma development. Gibberellins and auxins primarily induce ethylene production rather than serving regulatory purposes.

Aerenchyma formation in sugarcane is a constitutive process[54,55]. This implies that its formation is part of a developmental pathway or can be induced by the occurrence of abiotic stresses like hypoxia[56]. According to Grandis et al.[57], various combinations of developmental modules that are triggered by plant hormones and the environment appear to be responsible for its production. According to Leite et al.[55], sugarcane roots undergo cell wall alterations that result in the formation of a composite that appears to plug the gas cavities. These cavities appear to serve as spaces where the roots' remaining live cells can store and use gases for respiration. As a result of elevated amounts of ET, hypoxia has the secondary effects of promoting cellulase activity and aerenchyma development[53]. Sugarcane roots are extensively studied for the development of lysigenous aerenchyma[58,59]. Lysigenous aerenchyma involves cell separation, as well as programmed cell death, which results in the formation of gas-filled spaces[60]. The cell contents are entirely digested in lysigenous aerenchyma, leaving only the cell wall enclosing the gas cavity[61]. However, certain cells that are still present in the cortex create radial bridges right next to the lysing cells to keep the root's structural stiffness[62]. Cell expansion and pectin degradation in the middle lamella are the first steps in the development of lysigenous aerenchyma. Cell wall alteration and cell separation are the final steps[58]. Programmed cell death (PCD), and cell wall (CW) hydrolysis signal the beginning of lysigenous aerenchyma. Understanding PCD in aerenchyma formation does not fully elucidate the mechanisms controlling CW hydrolysis during aerenchyma development[63,64]. Glycosyl hydrolases such as xylanases and cellulases, as well as adjustments to xyloglucans and the breakdown of mixed-glucans, are necessary for CW alterations[65,55]. Studies have identified pectin as the first cell wall polysaccharide degraded during the formation of aerenchyma[55,63,64]. Acetyl esterases, endopolygalacturonases, galactosidases, and arabinofuranosidases are considered to attack pectin during the formation of aerenchyma in sugarcane roots, which is followed by the action of glucan/callose hydrolysing enzymes[53,58,59]. Pectin degradation is also required in many other cell wall degradation processes[66]. ET stimulates the development of lysigenous aerenchyma. Through the induction of programmed cell death and cell wall changes, its action aids in the opening of gas cavities inside parenchymatic tissues[53,58,67,68]. It is understood that the primary initiator of both induced and constitutive aerenchyma is the plant hormone ET[69]. ET signalling plays a significant role in aerenchyma formation. Cellular ultrastructural alterations induced by the ET signalling cascade include shrinkage and invagination of the plasma membrane, an increase in cytoplasmic electron density, and DNA cleavage. The activation of cell wall changes occurs concurrently[63,65], and some research suggests that complete cell wall degradation occurs with the development of lysigenous aerenchyma[65,70]. Furthermore, ET response factors (ERFs), NAC (for NAM (no apical meristem)), ATAF, CUC (cup-shaped cotyledon-apical meristem), and MYB (MYeloBlastosis virus gene) have been identified as transcription factor families involved in aerenchyma development[65]. Members of these families may control the expression of genes involved in lignin and phenylpropanoid production, but it is unclear how these families' members affect the development of aerenchyma. During aerenchyma formation in the sugarcane roots, immunolocalization revealed arabinoxylan debranching, homogalacturonan hydrolysis from the middle lamella, and β-glucan mobilisation[55]. An important precursor to cell wall attack is the negative control of homogalacturonan hydrolysis by the ET response factor RAV1[58,65]. Aerenchyma production, therefore, appears to be dependent on cell targeting brought on by the ET and auxin balance. This is followed by cell division and separation, controlled cell death, and the breakdown of hemicellulose and cellulose. Each stage establishes a conserved set of 'modules' that are utilised by other endogenous cell wall breakdown activities[66,57].

ET biosynthesis involves two key enzymatic steps (Fig. 3): S-adenosylmethionine is first converted to 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) by ACC synthase (ACS), and subsequently, ACC is oxidized to ethylene by ACC oxidase (ACO)[71]. Under waterlogging conditions, ACC levels rise due to increased ACS activity. ACC diffuses into aerated root zones, where it is converted to ET by ACO[72]. Additionally, ET accumulates rapidly due to both enhanced biosynthesis and entrapment within submerged tissues[73−75]. The understanding of ET signalling under hypoxic conditions is equally important. Hypoxia triggers the upregulation of ACS within hours, initiating ET production[76]. However, since the final step—catalyzed by ACO—is oxygen-dependent, it is paradoxical that ET synthesis increases under low oxygen. This paradox can be explained by the presence of limited oxygen in partially aerated tissues, which supports ACO activity and subsequent aerenchyma formation. Notably, aerenchyma fails to develop in fully anoxic tissues, further underscoring the importance of oxygen availability. The formation of a permeability barrier is another crucial aspect. As Armstrong et al.[77] noted, lateral roots act as 'windows' for ethylene efflux. The development of a barrier in other regions restricts ET diffusion, which may explain why aerenchyma does not form near lateral root emergence sites. ET is likely perceived by specific receptors in the cortical cells undergoing programmed cell death, which contributes to gas space formation[61].

Figure 3.

Lysigenous aerenchyma formation and its pathway waterlogging conditions. ACS: Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylix Acid Synthase; ACO: ACC Oxidase; CEL: Cellulase; XET: Xyloglucan Endotransglycosylase; MT: Metallothionein; RBOH: Respiratory Burst Oxidase Homolog.

Voesenek & Blom[78] proposed a mechanistic model for adventitious root formation in waterlogged plants. Flooding disrupts basipetal auxin transport, leading to its localized accumulation at the stem base. Simultaneously, increased ET levels in tissues just above the waterline enhance their sensitivity to auxin. This hormonal interplay induces hypertrophic growth and the initiation of adventitious roots[79]. Auxin serves as the principal regulator of this process by reprogramming shoot cells into root apical meristems[80,81]. Studies at the Sugarcane Breeding Institute, Coimbatore, demonstrated that all sugarcane cultivars showed elevated ET production under flooding. Notably, the tolerant cultivar Co 99004 exhibited significantly higher ethylene levels than the susceptible Co 86032, indicating a positive association between ET accumulation and adventitious root development in flood-tolerant genotypes. ET acts as a central modulator of morphological adaptation in hypoxic roots and shoots. Under waterlogging conditions, ET concentrations can reach up to 10 mL L−1 in plant tissues[79,82]. Due to its low solubility in water and diffusion rate—104 times slower than in air—ET becomes trapped in submerged organs. Tavares et al.[53] reported ethylene produced in roots can move internally through aerenchyma to reach aerial tissues, compensating for limited diffusion into the surrounding water. Consequently, both hypoxic and aerobic plant tissues upregulate ethylene biosynthesis during flooding. Elevated ET levels are a common feature in waterlogged plants compared to those in well-drained conditions[83]. Moreover, exogenous application of auxin has been shown to stimulate ethylene production, further promoting the formation of hypertrophy and adventitious roots at the stem base near the water surface[84]. In sugarcane, adventitious root induction from microshoots is enhanced by auxin analogues such as indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) and naphthalene acetic acid (NAA)[85]. Under flooding, ethylene either impairs polar auxin transport or increases tissue sensitivity to auxin, facilitating root development[86,87]. This heightened sensitivity, driven by ET accumulation, is a critical factor in activating root-forming tissues and initiating adventitious roots[79].

-

The distinction between exogenous and endogenous phytohormone mechanisms in controlling sugarcane's water stress responses is mainly in their origin, mode of action, and control dynamics within the plant (Table 1). Endogenous phytohormones refer to those naturally produced within plants[88]. Sugarcane hormones orchestrate physiological and molecular adjustments to prevent the response to water deficit stress. Conversely, exogenous phytohormone mechanisms involve the external administration of these hormones to the plant, which specifically augment or refine internal hormone signal transduction for enhanced water stress tolerance. Exogenous application of phytohormones, conversely, applies hormones like ABA, SA, or auxins from outside the plant, typically as foliar sprays or soil drenches, to artificially augment or stimulate the inherent hormone-induced stress response[89]. This strategy particularly functions by suddenly boosting the hormone concentrations in plant tissues prior to, or during, water stress, enabling plants to respond more resiliently to the upcoming challenges[90]. Such a preliminary boost allows for the induction of stress-associated gene expression, antioxidant enzyme activity, and defence-related physiological adjustments that enable plants to prepare for, and respond to, drought or water stress[91]. For instance, exogenous phytohormone application increases soybean drought stress tolerance[92]. The exogenous application of ABA to sugarcane seedlings subjected to drought has been shown to greatly enhance endogenous ABA content by approximately 40% or more, which in turn enhances the activities of antioxidant enzymes such as catalase (CAT1), superoxide dismutase, peroxidase, and ascorbate peroxidase. This enhanced antioxidant defence mitigates the build-up of deleterious ROS such as hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), thus reducing oxidative damage at the cellular level. Furthermore, proline content—a key osmolyte linked with drought tolerance—was considerably elevated following exogenous ABA treatment[93]. In addition, the most characteristic exclusive action of exogenous hormone treatment is the capacity to pre-condition and enhance the antioxidant system and stress signalling pathways of the plant before the occurrence of severe drought stress[93,94]. For example, Nong et al.[93] demonstrated that exogenous ABA treatment resulted in enhanced photosynthetic efficiency and biomass productivity in drought stress caused by PEG in sugarcane, which did not occur as rapidly or intensely with endogenous hormone production alone. This indicates that exogenous application can artificially enhance signalling networks and physiological responses to beyond what the endogenous system may be able to accomplish immediately under stress, serving as a useful mitigation tactic in agricultural environments. Other examples in varying crops such as wheat[95], tall fescue[96] demonstrate how exogenous phytohormones like salicylic acid (SA) trigger stress tolerance through regulating antioxidant enzymes and stomatal activity and therefore reducing water loss during drought conditions. Even though fewer explicit studies in sugarcane under SA or auxins have been conducted, data from comparative plants indicate that such treatments maximize enzymic defences and have a sustaining effect on photosynthesis under stress[91]. In addition, timing and localization are some other important differentiators. Endogenous hormones exert action at the place of their formation and transport, with time lags and diffusion constraints[97]. Exogenous applications, on the other contrary, can exert action upon specific tissues (e.g., foliar spray, root drench, or seed priming), providing localized action[98]. External application of auxin is generally not beneficial for sugarcane growth during temporary flooding stress during the cropping season[99].

Table 1. Comparison of exogenous and endogenous phytohormone mechanisms in sugarcane for water stress regulation

Phytohormones Endogenous phytohormone Exogenous phytohormone Origin Naturally produced within plants External application (e.g., foliar spray and root drench) Mode of action Promote internal signalling and physiological adaptations during stress Replicates internal signalling pathways for speed response Response timing Activation on stress perception, with slower onset Pre-condition to plant prior to stress, with faster onset Target sites Tends to act in site of synthesis or transmitted through phloem/xylem Can be targeted through discrete plant tissue for localized action Control Plant genetic and biochemical condition Externally by concentration, application method and timing Constrains May not react quickly under acute or intensive stress May pose phytotoxicity risks or ineffectiveness on excessive dosage or poorly schedule dosage -

It is well-established that ABA plays a central role in mediating plant responses to various abiotic stresses, including drought[100]. In monocot crops such as wheat, rice, barley, sorghum, and maize, ABA accumulation has been widely documented under stress conditions[101]. In sugarcane, Li et al.[22] observed an increase in ABA concentration under drought stress, which was further amplified following foliar application of ABA, particularly five days after treatment (DAT). Although the ABA levels initially spiked, the effect began to diminish gradually over time, likely due to the rapid metabolic turnover of ABA within plant tissues. Zhang et al.[102] demonstrated a linear relationship between ABA concentration in plant tissues and its catabolic rate. During stress, elevated ABA biosynthesis is often accompanied by enhanced breakdown into metabolites such as phaseic acid. This balance may help maintain ABA homeostasis under prolonged stress. A follow-up application of ABA at a critical time point might further support internal ABA levels and improve stress tolerance. One of the key roles of ABA under drought is the activation of antioxidant defence mechanisms. According to Khadri et al.[103], ABA treatment results in the overexpression of antioxidant enzymes, which help mitigate oxidative stress. In drought-stressed sugarcane, Li et al.[22] reported a significant increase in internal ABA concentrations following foliar ABA application. The treatment led to an increase in hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) content until 5 DAT, followed by a decline at 7 DAT. This transient H2O2 accumulation suggests an ABA-induced oxidative burst, which acts as a signalling molecule for activating downstream defence responses. Reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as H2O2, are common under drought stress and play crucial roles in stress signal transduction. Their accumulation, however, must be tightly regulated to avoid cellular damage. Zhao & Xu[104] reported that water stress stimulates ABA accumulation through increased ROS production, which in turn activates enzymes like catalase (CAT). The coordinated activity of ROS-scavenging enzymes—including glutathione peroxidase (GPX), which metabolizes H2O2, and superoxide dismutase (SOD), which generates H2O2—is considered a key indicator of plant responses to drought[105]. Environmental stressors, including drought, also enhance the expression and activity of these enzymes[106]. However, if drought persists, the antioxidant defence system may become overwhelmed, leading to ROS-induced damage and potential plant death. This vulnerability was highlighted by Li et al.[22], who observed a gradual increase in malondialdehyde (MDA) content—an indicator of lipid peroxidation—in drought-stressed sugarcane. Interestingly, MDA levels remained stable in plants that received both drought and ABA treatment, indicating that ABA-induced antioxidant responses helped suppress excessive ROS accumulation and cellular damage. The same study also showed that ABA application significantly boosted proline (Pro) accumulation, a well-known osmoprotectant that stabilizes proteins and membranes under stress. Neither drought alone, nor ABA application significantly increased proline content at 3 DAT, suggesting that the sugarcane cultivar ROC22 had not yet experienced sufficient stress. However, a sharp rise in proline was observed at 5 DAT, coinciding with intensified drought stress and ROS buildup, reflecting a delayed but robust osmotic adjustment mechanism[22]. Peroxisomal catalase plays a key role in detoxifying H2O2, though it is absent in chloroplasts. In these organelles, ascorbate peroxidase (APX) takes over this role, using ascorbic acid as a substrate to reduce H2O2[107]. Under drought stress, APX also indirectly supports ABA biosynthesis by maintaining ROS homeostasis. However, excessive ascorbic acid accumulation may suppress ABA synthesis by inhibiting APX activity, particularly under severe oxidative stress when CAT and APX activities decline, as observed in drought-only treatment (T1) compared to ABA-treated plants (T2)[22]. The APX–glutathione reductase (GR) cycle is vital for maintaining cellular redox balance. GR regenerates reduced glutathione (GSH) from its oxidized form (GSSG) using NADPH, allowing the continuation of the ascorbate–glutathione cycle[108]. High GR activity increases GSH availability, which supports other redox reactions and sustains ABA biosynthesis. However, the regulation of GR under abiotic stress remains poorly understood, suggesting the need for further research on its expression and role under drought conditions[106]. In Li et al.'s study[22], both drought and ABA application led to elevated GPX activity and a rise in H2O2 content. In ABA-treated plants (T2), enhanced expression of CAT and the ascorbate–glutathione system helped reduce H2O2 levels by 7 DAT, whereas in T1 plants (drought-only), insufficient antioxidative activity led to sustained oxidative stress. This contrast underscores the importance of ABA in orchestrating effective antioxidant responses under water-deficit conditions. Beyond its role in antioxidant regulation, ABA is a well-known regulator of stomatal conductance. During drought, increased endogenous ABA levels trigger stomatal closure, reducing water loss, and preventing desiccation[10]. Vargas et al.[109] reported that inoculation of sugarcane with beneficial nitrogen-fixing bacteria altered root gene expression and activated ABA-dependent signalling in shoots, thereby enhancing drought tolerance. These findings illustrate how endogenous and exogenous ABA, combined with microbial symbiosis, modulate hormonal pathways and confer stress resilience. Stomatal regulation via ABA has been further validated by Grantz & Meinzer[110], who linked leaf ABA content to stomatal conductance in sugarcane. However, leaf capacitance (C') did not correlate with conductance, suggesting that ABA and other xylem-borne signals from roots may independently regulate leaf gas exchange under mild drought. Supporting this, Smith et al.[111] showed that drying half the root system reduced stomatal conductance by 30% without affecting leaf water potential, reinforcing the idea of root-to-shoot signalling under water stress. While ABA is the primary hormone associated with drought responses, GA also plays a role in modulating stress tolerance, particularly by promoting cell division and elongation. GA is widely applied in sugarcane to improve growth and yield, primarily by increasing internodal length[112,113]. However, under drought, endogenous GA levels decline sharply[23], which may suppress growth. Exogenous GA application has been shown to mitigate these effects by restoring relative water content (RWC), and chlorophyll concentration in stressed plants. GA-treated sugarcane under drought stress showed no significant changes in root or leaf biomass compared to untreated drought-stressed plants. However, the extent of biomass reduction was lower in GA-treated plants (32%) compared to untreated ones (46%), indicating GA's potential to alleviate drought-induced growth inhibition. Moreover, shoot dry matter increased by 24.2% with GA application compared to untreated controls[112]. These results may be attributed to improved assimilate partitioning, as GA enhances phloem translocation of photoassimilates from leaves to internodes[114,115]. Botha et al.[116] also reported that GA-induced cell division and elongation contribute to biomass maintenance under stress. Despite these physiological benefits, GA had no significant impact on juice quality parameters such as Brix, polarity, purity, or commercial cane sugar content in drought-stressed sugarcane[112]. This suggests that while GA supports vegetative growth under drought, its influence on sugar accumulation is limited. Drought response in plants involves a complex interplay of multiple phytohormones. While ABA predominantly promotes stomatal closure and antioxidant defence, hormones like auxin, cytokinin, and ethylene can antagonize ABA signalling and impede drought adaptation. In contrast, SA, brassinosteroids, and JA tend to act synergistically with ABA in enhancing stress tolerance[18]. The cross-talk between these hormonal pathways enables a coordinated response to drought stress, balancing growth and survival mechanisms. Auxin and ABA, in particular, have been identified as key regulators of developmental and defensive responses during drought[23]. Inoculation with plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) that synthesize phytohormones has shown promising results in sugarcane. Vargas et al.[109] reported that such microbial associations can modulate drought-responsive gene expression—downregulating certain stress pathways in roots while activating ABA-dependent signalling in shoots—ultimately enhancing plant resilience.

The application of exogenous auxin in waterlogged plants has been extensively studied across crops due to its influence on ET biosynthesis under such conditions[79]. In sugarcane, Bamrungai et al.[99] reported that auxin had no significant effect on the number of adventitious roots across different crop developmental stages. However, after 7 d of treatment, genotypic differences in response became apparent. While auxin treatments (10, 20, and 30 mg L−1) significantly influenced the fresh weight of adventitious roots, dry weight remained unaffected, regardless of genotype or growth stage. In terms of varietal response, the application of auxin in sugarcane cultivars K93-219 and KK3 did not significantly affect plant height, leaf width, shoot number, fresh stalk weight, or green leaf retention at harvest[99]. Similarly, auxin had no notable impact on juice quality parameters—Brix, polarity, purity, fibre, and commercial cane sugar (CCS) content—across cultivars. However, auxin effects varied with growth stage, with the 10 mg L−1 being most effective in enhancing adventitious root number and fresh stalk weight. Among the two cultivars, K93-219 exhibited a more favorable response to auxin application under waterlogged conditions. Foliar-applied auxin can be absorbed through the stomata or epidermis and translocated via apoplastic or symplastic pathways[117]. It is primarily transported through the phloem and xylem to root tissues[118], with vacuoles and cell walls serving as major accumulation sites[119]. Environmental factors such as humidity and temperature, along with plant physiological traits, influence auxin absorption, transport, and accumulation efficiency[120]. However, evidence regarding the efficacy and optimization of combined exogenous hormone application in sugarcane under drought or waterlogging situations remains a significant research gap.

-

Traditional hormone delivery methods in agriculture, such as foliar spraying and soil drenching, have been widely employed to modulate sugarcane responses under abiotic stress conditions such as drought. However, these conventional techniques present several limitations that significantly compromise their effectiveness, especially in large-scale and stress-prone agricultural systems. One of the foremost challenges is poor temporal precision. Plant hormone efficacy is highly dependent on the timing of application in relation to stress phenology. For instance, ABA, a key hormone involved in drought tolerance, must be applied just before, or at the onset of stress, to induce the desired physiological responses such as stomatal closure, osmotic adjustment, or root elongation. If applied too late, the hormone may fail to mitigate damage, whereas premature application might lead to unnecessary growth inhibition or energy diversion. This narrow window for optimal application makes traditional methods unreliable and potentially wasteful[93]. In addition to temporal constraints, spatial inefficiency further reduces the utility of blanket spraying or drenching techniques. These methods typically distribute hormones uniformly across the field or crop canopy, ignoring the heterogeneous nature of stress distribution in field conditions. Within a plant canopy, microclimatic variation leads to differential stress perception, meaning that some leaves or roots may experience severe water deficit while others remain relatively unaffected. Uniform hormone application across such diverse zones result in over- or under-treatment in different areas, reducing the overall effectiveness and potentially triggering adverse side effects, such as hormone-induced senescence or inhibited photosynthesis in unstressed tissues. Moreover, soil drenching lacks site specificity, often leading to hormone leaching into non-target zones, which not only wastes resources but also poses environmental risks. Another critical issue is dosage inaccuracy, which arises from the manual preparation and application of hormone solutions. Variability in mixing concentrations and uneven application can result in inconsistent hormone exposure among plants. This inconsistency could lead to phytotoxic effects in sensitive plants or insufficient activation of stress responses in others, ultimately affecting uniformity in crop growth and yield performance. These risks are especially pronounced in high-value crops or during critical developmental stages when precise hormonal regulation is essential for ensuring optimal growth outcomes. labor-intensive nature is an added burden, particularly on large-scale farms where repeated applications within narrow phenological windows are required to achieve effectiveness. The necessity for skilled labour, combined with the logistical challenges of coordinating applications across vast areas, inflates operational costs and limits the scalability of traditional hormone delivery practices. Furthermore, labour shortages and variability in application techniques across workers can compound inconsistencies in timing, dosage, and coverage.

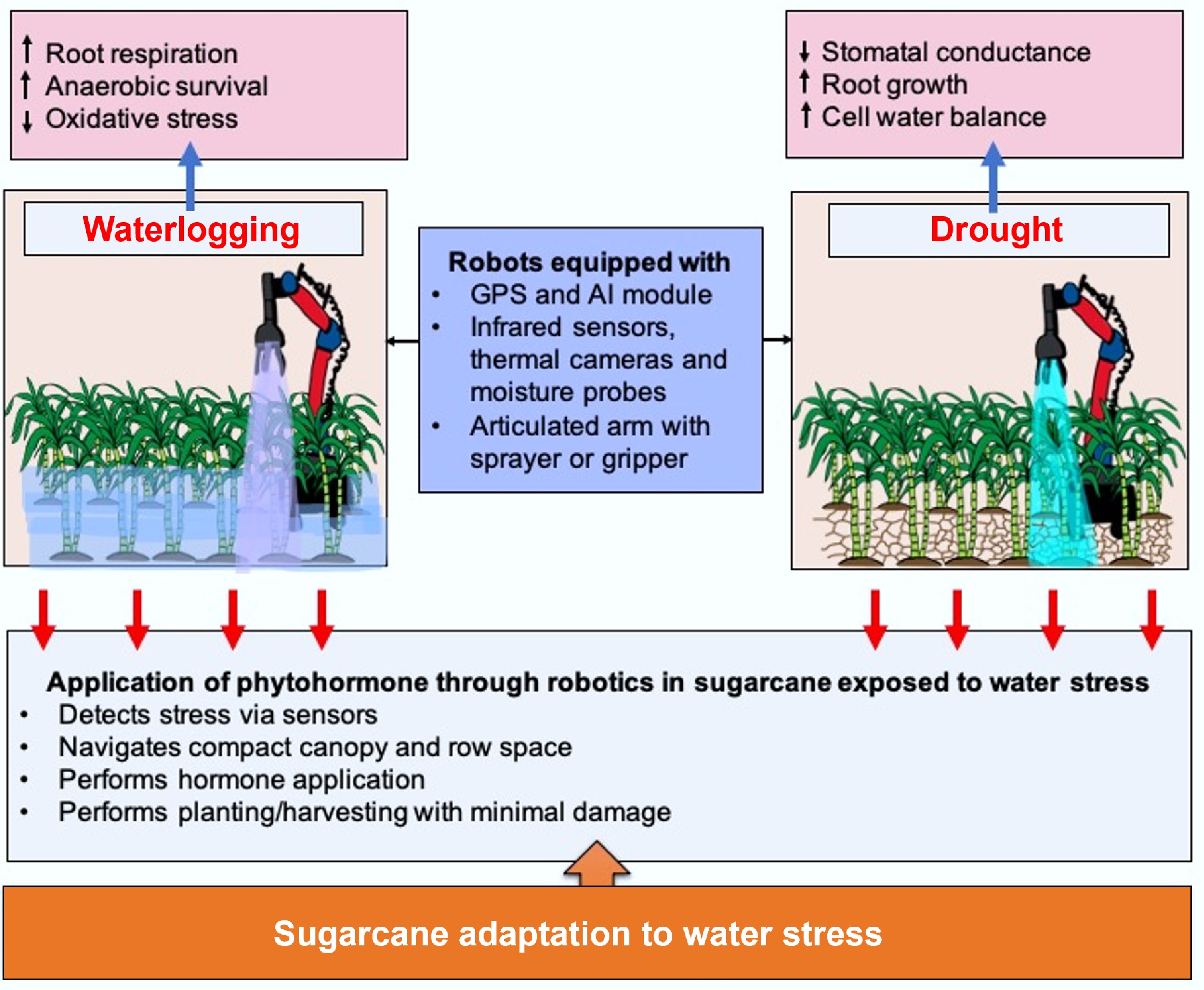

Collectively, these shortcomings underline the urgent need for precision hormone delivery systems that are adaptable to dynamic field conditions. Robotic platforms address conventional limitations through three core capabilities, viz., sensing and diagnostic, targeted application systems, and adaptive decision frameworks. Integration of agricultural robotics for exogenous phytohormone application in sugarcane for drought and waterlogging stress resilience helps enhance precision and efficiency. Robotics target sugarcane characteristics using a variety of innovative strategies that improve efficiency, minimize labour intensity, and maximize crop management (Fig. 4). The lengthy life cycle of sugarcane requires constant monitoring and labour-intensive measures. Self-driven robots are capable of moving around through dense sugarcane fields, finding their way around the compact row layout and compacted canopy that tends to impede hand inspection, thereby enabling regular monitoring throughout the long growth period[121]. During water deficit stress, robotic systems can monitor soil moisture content and water status of plants continuously using infrared sensors, cameras, and other technologies. Robots can deliver phytohormones like ABA or cytokinins to specific areas of the sugarcane fields when stress conditions are identified. The hormones improve drought resistance in the plant by regulating stomatal closure, stimulating root growth, and sustaining water balance in the cells. The robots' capability to penetrate the dense canopy of sugarcane and narrow row spaces enables them to target stressed plants precisely without causing damage. Robots used in sugarcane plantations are often equipped with advanced features like articulated arms with grippers to plant sugarcane sets correctly and manipulate plants gently so that they are not damaged. The robots also come with instructions to move along marked routes using lines or GPS to cover large fields systematically, with limited human involvement[121]. In addition, for waterlogging stress that negatively impacts oxygen levels in the supply to roots and overall plant well-being, robotic systems can identify early indicators of stress through real-time observations of soil saturation and plant reactions. Robots can then use phytohormones such as GA or ethylene inhibitors that assist plants in coping better with anaerobic environments, enhance root respiration, and mitigate toxic implications brought about by excess water. These treatments can mitigate yield loss and facilitate recovery from flooding stress[121]. These robots equipped with fuzzy real-time classifiers and vision systems, can detect leaf textures and variations that indicate weeds or plant health issues, even amidst the thick foliage[122]. This technological advantage accelerates field maintenance and reduces crop damage due to premature or imprecise interventions. Sugarcane's extended growth period can be enhanced through predictive modelling, supplemented by robot-based implementation. These predictions inform the robot schedules for irrigation, fertilization, or harvesting, dynamically adapting interventions to suit the long and variable development stages of sugarcane[123]. These predictions enable the robots to respond dynamically to changing field conditions, providing sugarcane plants with the right support to survive phases of waterlogging or drought. Autonomous robots, similar to the solar-powered Variable Swath herbicide Applicator, developed for weedicide application, can be adapted or designed to deliver phytohormones directly to sugarcane plants under drought and waterlogging stress conditions[124]. Kayode et al.[125] also developed a remote-controlled solar-powered pesticide sprayer vehicle which can be utilised for exogenous phytohormone foliar application in sugarcane to manage drought and waterlogging stress. These robots can be programmed to target specific zones within a field based on crop stress indicators, applying the correct dose of phytohormone only when required, thereby enhancing resource efficiency and crop resilience.

-

Sugarcane, a major C4 crop extensively cultivated in tropical and subtropical regions[126], is highly sensitive to fluctuations in water availability, with both drought and waterlogging causing substantial yield losses[12,13,127−129]. As climate variability intensifies, managing these stresses through physiological modulation becomes critical[130,131]. Comparative insights into the differential efficacy of exogenous phytohormones across various stress conditions and sugarcane genotypes—specifically drought and waterlogging—remain underexplored in the context of this crop. To facilitate a better understanding of their role under drought and waterlogging stress, a comparative overview based on the available literature is provided in Table 2.

Table 2. Comparative effect of exogenous phytohormones in sugarcane under water stress

Phytohormones Effect of drought Effect of waterlogging Ref. Abscisic acid (ABA) Promotes stomatal closure, osmotic adjustment, root growth, enhancement in antioxidant activity; increase in hydrogen peroxide

for 5 d after treatment; Activation of enzymes;

high ROS production; high relative water contentNo direct evidence available [22,93,104] Gibberellins (GAs) Rise in water demand; restoration of RWC; cell elongation increase;

rise in chlorophyll content; lower biomass; rise in shoot dry matter[111] Auxins (IAA, NAA) No direct evidence available Enhancement in nutrient uptake under anaerobic soil; adventitious rooting growth promotion but no significant changes across different developmental stages; no significant impact on juice quality [99] -

Plant stress responses are influenced by their genotype, developmental stage, as well as the duration and intensity of stress, and the interaction of multiple stressors. These responses are coordinated by a highly developed regulatory system that begins with stress perception and ends in a series of molecular processes that lead to phenotypic, physiological, developmental, and metabolic changes[132]. In spite of possessing complex defence mechanisms, exposure to stress can still lead to intracellular injury, such as cell wall disruption, DNA damage, lipid peroxidation, protein denaturation, and mitochondrial fragmentation. Externally, stress can manifest as inhibited seed germination, reduced biomass accumulation, changes in root architecture, and multilateral pleiotropic effects[133]. To counter these challenges, the use of encapsulated phytohormones is a viable strategy. Encapsulated formulations allow for targeted release and sustained release of hormones, enabling easy cellular uptake without requiring endogenous signal transduction or biosynthetic phytohormones directly, hence ensuring regulated growth and developmental responses during stress conditions[134]. Phytohormone nanoencapsulation can enhance their ability to promote plant growth and improve stress tolerance (Table 3). Nanotechnology-based encapsulation of phytohormones ensures slow and sustained release, protecting active compounds from degradation and providing longer-lasting effects during stress periods. Treated plants benefit from encapsulated phytohormones because they can directly absorb the released hormones without needing to activate their own signalling cascades or biosynthesis pathways. This approach has shown promise in mitigating the harmful effects of drought and waterlogging stress. Nanoparticles can also enhance water stress tolerance by improving root hydraulic conductance and water uptake in plants[135]. The ability of nanotechnology to provide sustained release kinetics, solubility efficiency, enhanced permeability, and stability is crucial for improving plant resilience to abiotic stresses[136]. For instance, in Arabidopsis thaliana, ABA hormone is delivered in plants using glutathione-responsive mesoporous silica nanoparticles for providing resistance to drought stress[137]. Similarly, in another study, ABA hormone was delivered through sol-gel encapsulation, using lignin to enhance drought resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa. The combination of ABA with alkali lignin and cetyltrimethylammonium bromide can effectively modulate stomatal behaviour in plants, thereby enhancing drought tolerance[138]. Though phytohormone-loaded nanocapsules have not yet been examined in sugarcane for drought and waterlogging adaptation; this approach can be utilized in this crop. Nanoencapsulation represents a viable approach to alleviating drought and waterlogging stress in sugarcane by meeting the crop's needs in terms of physiological and agronomic needs, including its long growth period and close canopy structure. Due to the extended growth period of 12−18 months of sugarcane, the continuous release of protective compounds is important. Sampedro-Guerrero et al.[134] showed that encapsulation provides a promising method for controlled release of most biologically active compounds while also enhancing the eco-friendliness of the biomaterials used as coatings. Encapsulation creates particles with high hydrophilic and lipophilic characters, improving their capacity to penetrate plant tissues. It is a process of encasing or coating a bioactive compound (the active material) in a protecting carrier to create capsules with enhanced biological properties[139]. The coating materials develop a matrix that serves as a barrier, shielding the core from critical factors like heat, oxygen, light, pH, and mechanical stress[140]. The capsules are very effective at preventing volatilization and protecting the core under harsh environmental conditions, thus minimizing degradation[141]. Nanoencapsulation, especially, makes it possible to release bioactive compounds like plant growth regulators, antioxidants and osmoprotectants in a controlled and sustained manner. This provides assurance of their presence at crucial phases in the life of plants[134], like sugarcane. Chitosan nanoparticles (CNPs) show great promise as carriers for pesticides and nutrients. These nanoparticles are capable of encapsulating active ingredients, allowing them to be delivered in a controlled and targeted manner[142]. This lowers the application rate and increases the long-term stability and efficacy of the chemicals. Additionally, research has established that CNPs greatly enhance the bioavailability of nutrients and efficiency of agrochemicals, reducing environmental effects and yielding higher crop harvests[143]. The dense canopy and height of sugarcane can restrict uniform application and uptake of traditional agrochemicals. However, nanoformulations enhance adhesion, spreadability, and penetrations, enabling effective foliar uptake even from the lower canopy positions. Meanwhile, root-applied nanoparticles deeper soil zones to assist water and nutrient uptake under stress[144]. Under drought stress, nanoencapsulated substances like silicon, proline, or trehalose help maintain osmotic balance, enhance antioxidant defence, and modulate stomatal conductance, thus enhancing the water retention and tolerance mechanism of the plant[134]. In flooded soils, nanoencapsulation may provide oxygen-releasing substances or ethylene inhibitors to the root zone and alleviate hypoxic stress and premature senescence. Nano formulations of beneficial microorganisms or soil conditioners also promote root integrity and rhizosphere under stress conditions[145]. In addition, targeted release of phytohormones, like ABA or silver nanoparticles, assists in modulating the stress responsive hormonal pathway, providing site-specific and effective regulation of plant physiological processes[146,147]. Nanoencapsulation is generally a highly effective and environmentally friendly method for abiotic stress management in sugarcane by ensuring coordination between the release and activity of stress protective agents with the crop's unique growth dynamics and architectural complexity[148]. These innovative approaches in this respect will help in enhancing the productivity of sugarcane under drought and waterlogging stress conditions.

Table 3. Nanoencapsulation phytohormone application in other crops related to sugarcane under water stress conditions

Crops Encapsulated phytohormones Mechanism of stress resilience Encapsulation method and capsule material used Effects recorded Ref. Maize

(Zea mays)AB, SA, IAA Stomatal closure regulation; antioxidant defence control; osmoprotection and growth promotion, ROS lowering − Higher drought tolerance, better grain filling and lower oxidative stress [152,153] Arabidopsis thaliana ABA Intracellular glutathione concentrations increased (as happens during drought stress), the

glutathione cleaved the disulfide bond, removing the decanethiol gatekeeper and enabling ABA release. Slower, more sustained release, providing longer-lasting ABA signalling within plant tissues during stress responsesSol gel encapsulation; amorphous silica through transpiration. Provides resistance against drought stress [137] Arabidopsis thaliana ABA Triggers stomatal closure, reduce transpiration In situ polymerisation;

ligninEncapsulated ABA retained >75% after 60 h UV; free ABA degraded rapidly;

High drought resistance[138] Rice (Oryza sativa) ABA − In situ polymerisation;

ligninRegulate plant stomata;

High drought resistance[138] Another approach is the use of automatic subsurface injectors for phytohormone delivery to cope with drought and waterlogging stress. Automated subsurface injectors can also deliver hormones directly to the root zone, which is especially important for waterlogging, where foliar uptake may be compromised. For instance, a mobile subsurface humidifier incorporates a main perforated subsurface injector and additional injectors to ensure uniform water saturation throughout the root zone. This approach allows for direct nutrient delivery to the root zone, synchronized with plant uptake[149]. This approach can also be utilized in sugarcane under waterlogging stress conditions. The injection of ET antagonists like silver thiosulfate or aminoethoxyvinylglycine (AVG) near the roots can mitigate the ET-induced root damage that typically occurs under anaerobic conditions. By directly targeting the root zone, automated subsurface injectors avoid the inefficiencies of foliar sprays or surface drenching, which are ineffective under waterlogged conditions where aerial parts are less responsive and ground runoff is common. This method not only conserves valuable phytohormone resources but also reduces the risk of phytotoxicity and off-target effects.

The scalability of both nanoencapsulation and subsurface injection methods is also a major challenge for crops like sugarcane. In the case of nanoencapsulations/nano-formulations, product cost of manufacture, production volume, and environmental safety of nanomaterials are the issues to address prior to commercial-scale application. Advances in green synthesis of biodegradable nanocarriers through advances offer a pathway to reduce ecological risks and achieve cost-effectiveness[150]. For automated injection systems, mechanization that is appropriate for the tall and dense environment of sugarcane needs to be optimized for field practicality and labour effectiveness. Mobile platforms with integrated sensors for plant status and soil moisture may further improve precision delivery, but they involve considerable R&D and investment. Additionally, sugarcane's extended growth cycle necessitates hormone delivery systems capable of providing the hormone via long-term sustained release or repeated programmable dosages to coincide with various growth phases and varying stress periods. Integration with the precision agriculture tools such as remote sensing and automated monitoring would enhance timing and dosage of treatments. Integration of nanoencapsulation with robotic injection presents a multidisciplinary solution to directly tackle growth cycle length, canopy density, and soil heterogeneity. Nanotechnology-based delivery systems, such as nanoencapsulation and automated subsurface injectors, hold great potential for boosting sugarcane resistance to drought and waterlogging stress. These methods require, however, additional development and calibration to sugarcane unique characteristics, including its protracted growth period, dense canopy, and scalability for field-level use. Phytohormone nanoencapsulation provides long-term and targeted release of bioactive molecules, shielding them from degradation and providing slow, controlled bioavailability. This creates extended effect longevity during times of stress and reduces the necessity for plants to stimulate their own biosynthetic responses, as evidenced in Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa experiments using ABA-charged mesoporous silica and lignin-based nanoparticles[134,151].

-

Looking ahead, the strategic application of exogenous phytohormones has significant potential for waterlogging and drought stress management in sugarcane. There is a need to further study the application of exogenous phytohormone in sugarcane under water stress conditions on juice quality. However, further development is necessary before routine adoption in commercial agriculture. Furthermore, precise determination of the optimal timing, dosage, and mode of hormone application is essential since the same hormone can have extremely variable responses based on the developmental stage of the plant, level of stress, and dynamic interactions between hormones. For instance, precise control over ABA applications is required to achieve optimal water-conserving benefits during drought without causing undesirable side effects, such as growth inhibition or excessive stomatal closure under milder environmental conditions. In addition, it is critical to extend research beyond controlled-environment and greenhouse studies to fully evaluate these treatments under actual field conditions, where sugarcane is subjected to various and fluctuating stresses at once, such as drought, waterlogging, heat, and pest pressures. Well-designed field trials in various agroclimatic regions and soil conditions are required to determine the efficacy and safety of exogenous hormone treatments (both single and combined) for enhancing yield and cane quality under multiple stress conditions. Sustainability also represents an important issue. Large-scale application of phytohormones might affect the cost of farmers and become a threat to the environment if hormones leach into water bodies or interfere with soil microbial populations. To address these concerns, technological innovations such as slow-release products and the use of hormone-producing microbial consortia (bioinoculants) provide targeted, longer-lasting, and possibly cost-efficient solutions. Omics technologies (transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) applied to systems research can also delineate the molecular networks involved in hormone action to enhance stress resilience. Concurrently, exogenous hormone research findings can support genetic improvement initiatives to facilitate breeding or genetic engineering of cane with maximally effective endogenous hormone responses toward water-stress tolerance. For deployment in the field on a practical scale, precision agriculture technologies—such as drones and smart sprayers—will be essential for delivering hormones at the correct location and time, minimizing wastage while ensuring maximum effectiveness.

-

The exogenous application of phytohormones presents a promising strategy for managing water stress in sugarcane. These naturally occurring signalling compounds play a crucial role in enhancing the plant's resilience by modulating physiological and biochemical pathways associated with stress tolerance. Their external application has been shown to promote deeper root development, regulate water uptake and transport, boost antioxidant defence mechanisms, and stabilize plant performance under both drought and waterlogging conditions. By leveraging the regulatory potential of phytohormones, it is possible to strengthen the adaptive responses of sugarcane to adverse environmental conditions, thereby ensuring sustainable growth and productivity in fluctuating climatic scenarios.

Future research should focus on developing smart delivery systems for phytohormones, such as nano-formulations, biodegradable encapsulation, and controlled-release matrices. These technologies can ensure targeted, timely, and efficient hormone release, minimizing wastage and maximizing physiological impact. Investigating the synergistic effects of multiple phytohormones (e.g., ABA, JA, SA, and ET) when applied exogenously could provide a holistic approach to stress management. Tailoring combinations based on the type and severity of water stress could yield more robust adaptive responses. Exploring genotype-specific responses to exogenous hormone application will allow for customized stress management strategies. Identifying varieties that exhibit stronger responsiveness to certain phytohormones under drought or waterlogging will aid in developing targeted interventions. Coupling hormone application with real-time monitoring systems—such as soil moisture sensors and plant stress indicators—can help schedule precise applications, thereby aligning hormonal intervention with critical phenological stages and stress onset. Employing genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics will deepen our understanding of hormone-regulated stress pathways in sugarcane. This knowledge can support the identification of molecular biomarkers to monitor stress response and predict hormone efficacy. Research should aim to develop eco-friendly, cost-effective, and farmer-adaptable hormone formulations suitable for wide-scale field use. Such solutions should be optimized for long-duration crops like sugarcane that face prolonged stress periods. By addressing these future directions, the exogenous use of phytohormones can be transformed into a precision tool for stress adaptation in sugarcane, ultimately contributing to climate-resilient agriculture and sustained productivity.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Misra V, Mall AK; writing - draft manuscript preparation, literature review: Misra V; writing - review and editing, supervision: Mall AK. Both authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

There is no funding support for this paper.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Water stress significantly impacts sugarcane productivity.

Exogenous phytohormones increase sugarcane resilience, current research is however limited.

Nano subsurface robotics will enhance hormone delivery in sugarcane.

-

# Authors contributed equally: Varucha Misra, Ashutosh Kumar Mall

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article. - Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Misra V, Mall AK. 2025. Application of phytohormones exogenously to ameliorate sugarcane's response to water stress. Agricultural Ecology and Environment 1: e006 doi: 10.48130/aee-0025-0006

Application of phytohormones exogenously to ameliorate sugarcane's response to water stress

- Received: 08 July 2025

- Revised: 01 September 2025

- Accepted: 12 September 2025

- Published online: 13 October 2025

Abstract: Phytohormones, signalling molecules synthesized in minute amounts, coordinate key elements of plant development, growth, and environmental stress adjustment. These regulators consolidate varied stress signals, modulate downstream defence reactions, and set cooperative signalling networks indispensable for vigorous plant resilience. Water stress, including drought as well as waterlogging, significantly affects plant adaptation and has phytohormones acting as pivotal mediators. Sugarcane (Saccharum spp.), a long-season crop grown over heterogeneous environments, is subjected to extreme water stress limitations. Areas of unpredictable rainfall subject sugarcane to fluctuating drought and waterlogging, in direct conflict with productivity. Whereas phytohormones are well-documented players in abiotic stress response, mechanisms unique to sugarcane are not well understood, specifically regarding exogenous hormone applications. This review specifically addresses sugarcane's responses to water stress extremes, emphasizing actionable insights from exogenous phytohormone applications to bridge fundamental science and agronomic practice. This review aims to push toward targeted crop management in water-variable environments.

-

Key words:

- Abscisic acid /

- Aerenchyma /

- Ethylene /

- Phytohormone /

- Sugarcane /

- Drought /

- Waterlogging