-

Energy drinks are beverages that typically contain stimulant compounds, most commonly caffeine, along with various other ingredients such as vitamins, amino acids, and herbal extracts[1−3]. These drinks are marketed to provide a temporary boost in energy, alertness, and cognitive function. They are often consumed to combat fatigue and enhance physical or mental performance. However, they may also pose risks if consumed excessively due to their high caffeine and sugar content[1−3].

There is a difference between energy drinks, soft caffeinated drinks and sports drinks. Soft caffeinated drinks are non-alcoholic beverages that contain caffeine as one of their primary ingredients. Unlike energy drinks, which often contain additional stimulants and additives, soft caffeinated drinks typically have a milder caffeine content and may include flavors such as cola, root beer, or citrus[4,5].

Sports drinks are beverages specifically formulated to help athletes rehydrate, replenish electrolytes, and refuel during or after intense physical activity. They typically contain water for hydration, carbohydrates (in the form of sugars) for energy, electrolytes such as sodium and potassium to replace those lost through sweat, and sometimes vitamins or other additives[6].

Sports drinks are designed to help athletes maintain performance and recover more quickly from exertion. However, they may not be necessary for casual exercisers or individuals engaging in low-intensity activities[7].

Herbal extracts in energy drinks

-

Herbal extracts are often included in energy drinks to provide additional perceived benefits or to enhance the drink's marketing appeal[1,8]. These extracts may claim to offer various health benefits or synergize with the stimulant effects of caffeine. Ginseng and guarana are the herbal extracts most frequently contained in energy drinks. Ginseng is a popular herbal remedy believed to improve energy levels, mental clarity, and physical stamina. It is often included in energy drinks for its purported adaptogenic properties, which may help the body better cope with stress and fatigue[9]. Guarana is a plant native to the Amazon basin, and its seeds contain high levels of caffeine. Extracts from guarana are often added to energy drinks to provide an additional source of caffeine beyond that derived from synthetic sources[10].

Furthermore, some energy drinks include ginkgo biloba extract to promote mental clarity and focus. Ginkgo biloba extract is derived from the leaves of the Ginkgo tree and is believed to improve cognitive function and circulation[11]. While not strictly an herbal extract, taurine is an amino acid found naturally in meat and fish. It is commonly included in energy drinks for its purported role in enhancing athletic performance and mental alertness, although scientific evidence supporting these claims is limited[12,13]. Green Tea Extract and Yerba Mate may be added to energy drinks for their stimulant properties and potential health benefits, such as improved focus and mental alertness[14]. Green tea extract contains antioxidants called catechins, as well as a moderate amount of caffeine. Yerba mate is a South American plant whose leaves are brewed to make a caffeinated beverage. While these herbal extracts are commonly found in energy drinks, their efficacy and safety may vary. Additionally, the overall safety of energy drinks, including their herbal ingredients, is the subject of debate and concern[15,16].

Caffeine in energy drinks

-

Caffeine, a purine alkaloid, is a widely used psychostimulant found in coffee beans, cola nuts, tea leaves, yerba mate, guarana seeds, and cocoa beans[3,17].

Caffeine influences both cognitive and physical functions by antagonizing adenosine A1 and A2a receptors in the central nervous system and peripheral tissues[18]. Caffeine stimulates the release of adrenaline, boosts levels of dopamine, noradrenaline, and glutamate, enhances heart and respiratory rate, mobilizes intracellular calcium stores, and modulates fat and carbohydrate metabolism in the human body[19]. These effects, including the promotion of lipolysis, are facilitated by its ability to inhibit phosphodiesterase enzymes. Dosages ranging from 1 to 4 mg/kg body weight have been shown to heighten alertness, concentration, and reaction time. Moreover, doses spanning 3 to 6 mg/kg body weight can augment cognitive abilities, motor skills, and overall physical performance across diverse sports disciplines[20]. Recognized as a supplement with extensively documented effects, it is frequently utilized to enhance exercise performance. Its supplementation proves beneficial in various athletic scenarios, notably improving endurance and performance in short-term, high-intensity activities[21].

The content of caffeine in beverages ranges from 4−180 mg/150 ml for coffee to 24−50 mg/150 ml for tea, 15−29 mg/180 ml for soda cola, and more than 160 mg/355 ml for energy drinks[22].

Several factors can influence the cardiovascular side effects of caffeine consumption. Some of the key factors include dosage, individual sensitivity, habitual or occasional intake, caffeine tolerance and tachyphylaxis, timing of consumption, and hydration status.

Higher doses of caffeine are more likely to cause adverse effects such as increased heart rate and blood pressure, mainly in subjects who are non-habitual consumers[1,3,22]. Regular caffeine consumers may develop tolerance to some of its effects, including cardiovascular effects. However, tolerance levels can vary among individuals and may not fully protect against adverse cardiovascular responses, particularly at high doses[22−24].

One of the side effects that causes the greatest concern is the appearance of arrhythmic phenomena induced by caffeine consumption. The mechanisms underlying caffeine's potential impact on arrhythmias are not yet fully understood. However, current evidence suggests that moderate caffeine intake is generally well tolerated and does not appear to significantly increase the risk of arrhythmias[22−26]. As highlighted by the European Food Safety Authority (ESFA) single doses of caffeine up to 200 mg (approximately 3 mg/kg body weight for a 70 kg adult) do not cause safety concerns[27]. The specific recommended limits may vary based on factors such as age, individual sensitivity to caffeine and existing health conditions[27].

Consumption of energy drinks

-

The consumption of energy drinks has been constantly increasing in recent years as highlighted by the data relating to market sales. In 2022, the market was valued at USD

${\$}$ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ ${\$} $ These data illustrate a consistent upward trend in the global energy drinks market, driven by factors such as the popularity of these drinks for providing instant energy and mental stimulation. Increased health consciousness and changes in consumer lifestyles are also contributing to this sustained growth[32,33].

Consumers of energy drinks vary widely, but certain demographic groups are more commonly associated with the consumption of these beverages. The primary consumer groups were young adults and college students who may use them to combat fatigue, stay awake for late-night studying, or boost energy levels during busy schedules[32,33].

Furthermore, some individuals involved in sports and fitness activities consume energy drinks to enhance performance and endurance. The caffeine and other ingredients in these drinks are believed to provide a temporary energy boost[32,33].

Recent literature on energy drinks highlights healthcare personnel as the category with the highest consumption after young people and athletes, suggesting the setting up of specific information campaigns dedicated to these professionals[34,35].

Healthcare professionals play a vital role in ensuring uninterrupted care for patients, often working tirelessly throughout the day and night. The demanding nature of their work, particularly during rotating shifts or overnight hours, presents a challenge in staying awake due to the body's natural circadian rhythms. To address this, numerous nurses rely on caffeine, which is commonly found in coffee, tea, and high-energy drinks (EDs), as a readily available stimulant[34,35].

The aim of this review was to analyze the available literature relating to caffeine consumption in healthcare personnel and identify risk trajectories in the excessive consumption of energy drinks and drinks with a high-caffeine content.

MEDLINE, Scopus and Web of Science were used to search for available research. In brief, a combination of terms relating to energy drinks (eg, 'highly caffeinated beverages' and 'energy drink') and healthcare personnel (eg, 'nurse' and 'medical doctor') were used. For studies to be included in this review, they had to report on primary research, be published in peer-reviewed journals, and be written in English.

-

Articles analyzing the consumption of energy drinks in young people and athletes were excluded, focusing on reports related to the consumption of caffeine-rich drinks by health workers (Table 1).

Phillips et al.[34] explored nurses' use and knowledge of caffeine and high energy drinks in three countries: Italy, South Korea and the US. Nurses in each country completed a survey on caffeine and EDs use and knowledge. In a population of 182 nurses, caffeine use was high. They found that 92% of nurses in Korea, 90.8% in Italy and 88.1% in the US have at least one cup of coffee a day while 64% of Koreans and 11.9% of those in the US had at least one ED per day. In Korea 68% of nurses (Italy 63.1% and 35.8% US) had at least one cup of caffeinated tea per day. About demographic data, most nurses in all three countries were women, with female representation at 73.8% in Italy, 98% in Korea, and 89.6% in the US. The US had the highest percentage of married nurses at 50.7%, surpassing Italy with 41.3% and Korea with 18%. Over half of nurses in Korea (58%) and the US (56.7%) reported their colleagues consume EDs at work[34]. Interestingly, the great majority of responders agreed there is a need to educate nurses about EDs effects.

A study by Higbee et al.[36] determined if there were differences in sleep quality, sleep quantity, and perceived stress levels in nursing students who consume energy drinks compared with those who consume other sources of caffeine and those who abstain.

Nursing students who consumed energy drinks reported poorer sleep quality, fewer sleep hours, and higher levels of perceived stress than caffeine-only consumers and non-caffeine consumers. Authors concluded that nursing students may be unaware of the relationships among energy drink consumption, sleep quality, sleep quantity, and perceived stress levels[36].

A Canadian study evaluated the lifestyle behaviors (prevalence of nicotine, caffeine, cannabis, sleep-promoting medication, and alcohol use) and the association between job stress, sleep quality, anxiety, and depression among registered nurses working night shifts in the COVID-19 era[37].

The results showed a strong positive association between sleep disturbance, and depression r (19) = 0.50, [p = 0.029, 95% CI, 0.06, 0.78]. A positive correlation was found between higher levels of reported anxiety and sleep disturbance r (19) = 0.69, [p = 0.001, 95% CI, 0.34, 0.87]. There was a positive correlation between depression and occupational exhaustion r (17) = 0.56, [p = 0.021, 95% CI, 0.10, 0.82]. Anxiety was significantly related to occupational exhaustion r (17) = 0.65, [p = 0.005, 95% CI, 0.24, 0.86] and depersonalization r (17) = 0.52, [p = 0.005, 95% CI, 0.06, 0.80], but not significantly related to personal accomplishment r (17) = −0.34, [p = 0.185, 95% CI, −0.70, 0.17]. Authors concluded that Canadian nurses working night shifts showed a significant positive relationship among sleep disturbance, anxiety, and depression. Furthermore, most nurses reported using at least one or more of the following substances: sleep-promoting medication, nicotine, alcohol, and cannabis[37]. Consumption of caffeine was evaluated using the Caffeine Expectancy Questionnaire (CaffEQ). The CaffEQ is a 47-item self-report evaluation that measures a range of expectancies for caffeine including withdrawal/dependence, energy/work enhancement, anxiety/negative physical effects, social/mood enhancement, appetite suppression, physical performance enhancement, and sleep disturbance. The mean for the questions was 2.69 (on a 1−5 scale) suggesting that the average response was that participants were 'a little likely' to engage in behaviors related to caffeine dependence[37].

Another study examines the caffeine and energy drink habits of clinical nurses, investigating relationships with their sleep quantity, sleep quality, and perceived stress levels[38]. Consumption of energy drinks was reported in 107 subjects (22.5%), while 299 nurses reported caffeine-only consumption (62.8%). In the group of subjects who consume EDs, 82% drink only one can, 9.3% report drinking two cans and only 3.7% drink three or more cans. Nurses who consumed energy drinks had poorer sleep quality and fewer sleep hours compared with caffeine-only consumers and noncaffeine consumers. Nurses who consumed energy drinks also had increased levels of perceived stress than noncaffeine consumers. A significant relationship was found between energy drink consumption and sleep quality, sleep quantity, and perceived stress levels. Furthermore, this study highlighted the impact of stress on lifestyle habits.

A literature review and survey study by Smoyak et al.[39], published in the Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, focused on EDs, both with and without alcohol. It compared responses from psychiatric nurses and college students, exploring their knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding these drinks. The study highlighted the increasing popularity of EDs, especially among teens and young adults, and documented a recent trend of mixing EDs with alcohol. The study found that not only the youth and young adults, who are the highest users of these products, but also faculty, clinicians, and administrators were often uninformed, misinformed, or unaware of the dangers associated with such use.

Results of this study were in line with other studies that explored consumption of energy drinks in students of medical courses[35,40,41].

In a survey conducted on 500 undergraduate medical school students an increase in the consumption of energy drinks was reported in 24% of the subjects[40,41].

Table 1. Perspective and cohort studies on caffeine consumption in healthcare personnel and nursing students.

Reference Population Results Phillips et al.[34] 182 nurses Caffeine use was high with 92% of nurses in Korea, 90.8% in Italy and 88.1% in the US. Okechukwu et al.[37] 22 nurses CaffEQ score was 2.69 on a scale of 1−5. Higbee et al.[38] 476 nurses Energy drinks consumption 107 subjects (22.5%), caffeine only consumers 299 (62.8%), non-caffeine consumers 70 subjects (14.7%). Mattioli & Sabatini[41] 500 undergraduate

medical school students24% students reported that an increase frequency and quantity of energy drinks consumption. Higbee et al.[36] 272 nursing students Nursing students who consumed energy drinks reported poorer sleep quality, fewer sleep hours, and higher levels of perceived stress than caffeine-only consumers and non-caffeine consumers. All these studies highlight the lack of information on the acute and critical effects of drinks with a high caffeine content even though subjects with a high level of medical knowledge were assessed.

The further aspect that emerges from the literature is the risk associated with the consumption of drinks with high caffeine content and the side effects that can be induced in personnel working in emergency conditions and with the need for quick response.

Guilbeau[42] discussed the health concerns and workplace safety issues related to the consumption of energy drinks, particularly focusing on the adverse effects on the central nervous system and both mental and physical effects.

Dennison et al. highlighted the role of occupational and environmental health nurses in raising awareness and advocating for public health and safety regarding the consumption of energy drinks[43].

The increasing reports of adverse health events related to energy drinks raise concerns about their safety, particularly in the context of emergency department visits. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) reported significant growth in the number of emergency department visits associated with energy drinks[44]. According to The DAWN (Drug Abuse Warning Network) Report in 2013, emergency department visits related to energy drinks surged from 1,500 in 2005 to nearly 21,000 in 2011. This represents a substantial and alarming increase over a relatively short period[44]. In 2022, 32 substances were added to the DAWN drug classification system. After investigating each new entry, all substances were added to the system and assigned to existing drug categories. Of the 32 substances, nine (28.1%) were classified as illicit, and 23 (71.8%) were classified as non-illicit. Energy drinks belong to non-illicit categories[45]. The increase in emergency department visits suggests a correlation between energy drink consumption and adverse health events. These events may include symptoms such as palpitations, increased heart rate, high blood pressure, and, in severe cases, cardiovascular or neurological issues[46−51].

Furthermore, this rise in emergency department visits may reflect misuse or overconsumption of energy drinks, either by drinking excessively within a short period or by combining energy drinks with other substances[52−54].

-

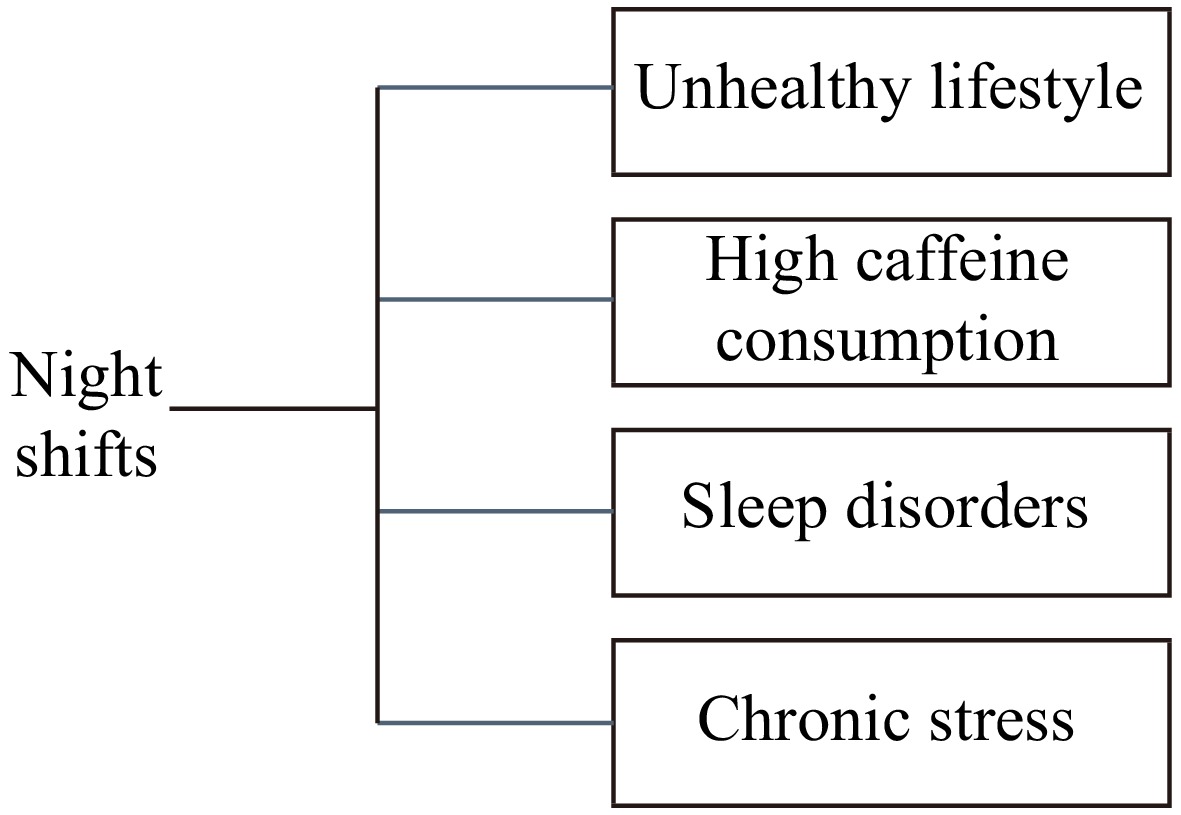

Night shift stress can significantly impact nurses, as they often work in healthcare settings that require 24/7 staffing (Fig. 1). Night shifts introduce a unique set of challenges and stressors that can affect both the physical and mental well-being of nurses[55−57]. In addition to the acute effects, the persistence of shifts determines an increased risk of developing chronic non-communicable diseases[56−59].

The main effect of night shifts is the disruption of natural circadian rhythms, which leads to disturbances in sleep-wake cycles. This disruption can contribute to fatigue, sleep disorders, and difficulty in maintaining a consistent sleep pattern[55,60−62].

Furthermore, working during the night can lead to insufficient and fragmented sleep. Chronic sleep deprivation is associated with a range of health issues, including impaired cognitive function, decreased alertness, and an increased risk of accidents or errors.

In addition, night shifts may involve fewer staff members, leading to an increased workload and responsibilities for those on duty[63]. Nurses working night shifts may need to handle a wide range of tasks, including patient care, monitoring, and responding to emergencies[63]. Changes in diet has been reported in subjects working night shifts[64−66]. de Rijk et al.[64] observed a higher contribution of energy from the 'sweet and fat' and 'sweet and sour' taste cluster during the night shift than outside the night shift. They also found that night shift working nurses consumed more energy from the 'sweet and fat' taste cluster during the night shift than outside the night shift. However, this higher energy intake during the night shift did not result in a higher total daily energy intake from the 'sweet and fat' taste cluster than the reference population[64]. The temporal misalignment between light–dark and wake–sleep, eating–fasting, and activity–rest cycles[66] has been linked to metabolic dysregulation, impacting food intake[67,68]. Consequently, shift workers often modify their lifestyle habits, including food consumption[66−68]. These modifications are also influenced by the social challenges associated with shift work. Research in this area indicates that shift workers, particularly those on night shifts, tend to adopt less nutritious diets compared to their day-working counterparts[69]. Moreover, their meals are frequently consumed late at night[70].

The increase in the consumption of energy drinks is part of this context of alteration of eating habits during night shifts. Energy drinks are highly energetic drinks, but. while coffee has some favorable effects on health due to the presence of antioxidants, EDs have not yet demonstrated favorable effects on health[23,71−73].

Among the effects that individuals suffer and which can be perceived differently, night shifts often result in limited social interaction and reduced support from colleagues, friends, and family[74]. The isolation can contribute to feelings of loneliness and may impact mental well-being. Nurses may experience emotional fatigue due to the demands of working during unconventional hours[74,75].

The chronic stress associated with night shifts has been linked to mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, and burnout. The recent COVID-19 pandemic has led to a significant increase in stress and burnout among healthcare workers[76−79].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare personnel were subjected to high levels of stress which led to changes in lifestyle habits. In many cases an increase in unhealthy lifestyle has been observed. Changes in eating and drinking habits were frequent both in the general population and in healthcare personnel[80−82]. The consumption of tea has been found to positively influence various aspects of mental health, including reduced anxiety, enhanced cognition, and increased brain function[82,83]. Similarly, coffee has garnered considerable scientific interest regarding its impact on mood and emotions. Consuming one cup of coffee every four hours has been associated with mood improvement. Additionally, low to moderate doses of caffeine (equivalent to two to five cups of coffee per day) have been shown to reduce anxiety[82,83].

The relationship between the consumption of coffee and caffeinated drinks and stressful situations is complex and the recent pandemic has further complicated it[83−85].

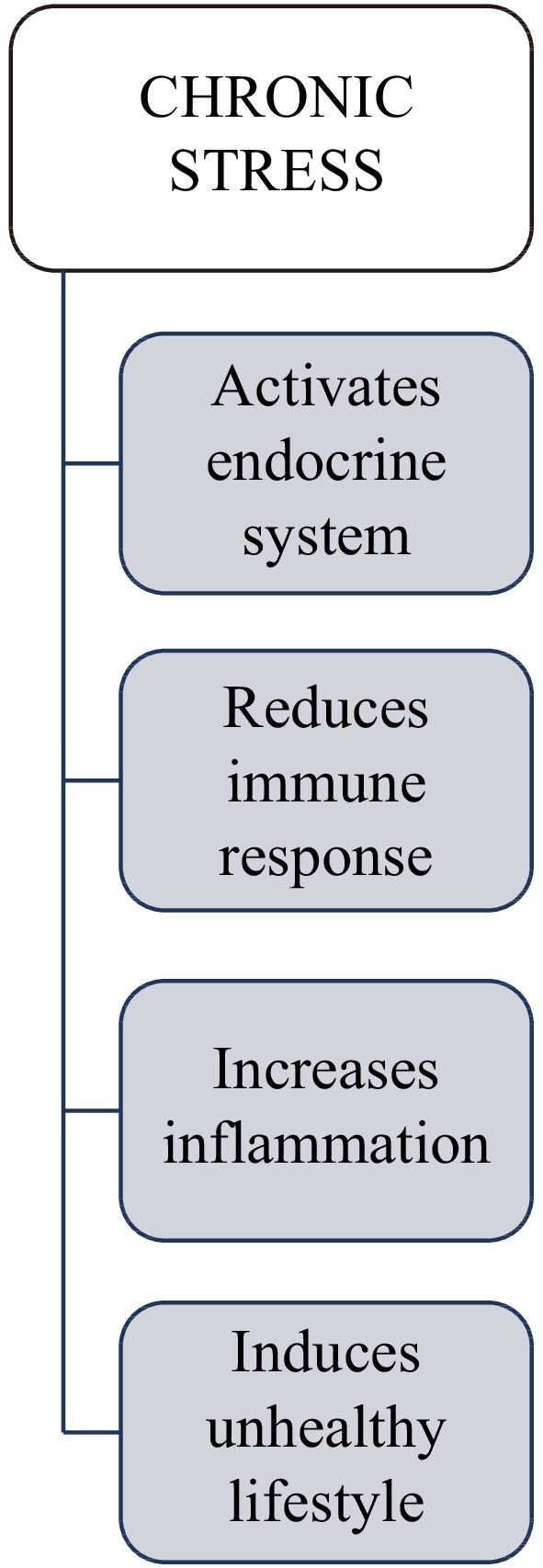

Stress has significant effects on both the endocrine system and the cardiovascular system through the release of stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline (Fig. 2). The adrenergic system, responsible for the 'fight or flight' response, is activated in response to perceived threats and the activation increases heart rate and blood pressure. Prolonged activation of the adrenergic system can reduce the immune response and result in chronic low-grade inflammation[84]. Furthermore, stress determines a change in lifestyle, especially diet including beverages, sedentary lifestyle and changes in sleep[31,32,76,77,85]. An unhealthy diet has been linked to chronic inflammation and atherosclerosis[77,78,86] (Fig. 2).

Understanding these mechanisms highlights the importance of stress management for overall health and well-being. Strategies such as mindfulness, relaxation techniques, regular exercise and physical activity, and a healthy lifestyle can help mitigate the negative impacts of chronic stress on both the adrenergic system and inflammatory responses[77,86−88]. Addressing stress effectively can play a key role in preventing or managing various health conditions associated with chronic inflammation.

Implementing strategies to cope with night shift stress is essential. This may include creating a conducive sleep environment during the day, practicing good sleep hygiene, and incorporating relaxation techniques[88]. Healthcare organizations can contribute to nurse well-being by implementing supportive policies, providing adequate staffing levels, and offering resources for managing stress.

Creating a positive work culture that acknowledges and addresses the challenges of night shift work is crucial.

It's important for nurses and healthcare organizations to recognize the impact of stress associated with night shifts and work collaboratively to implement measures that promote well-being and mitigate the negative effects.

Finally, it is necessary to increase knowledge of the effects of chronic intake. and prolonged consumption of drinks with a high caffeine content and in the case of energy drinks, knowing the different components included in these drinks.

-

The groups identified as at high risk for the consumption of energy drinks are young people and athletes. Healthcare personnel have different and unique characteristics compared to the groups.

The first difference concerns the knowledge and training of medical personnel compared to other consumer groups. Health workers typically have a deeper understanding of the potential health implications of consuming energy drinks. They are likely to be more aware of the risks associated with excessive caffeine intake, such as increased heart rate, hypertension, and potential interactions with medications or pre-existing health conditions. Health workers have access to scientific literature, continuing education programs, and peer-reviewed research on the effects of energy drinks. This knowledge may influence their attitudes and behaviors regarding energy drink consumption, as they are more likely to critically evaluate the evidence and make informed decisions.

Furthermore, many health workers, especially those in hospitals or emergency care settings, work long hours and irregular shifts, which can lead to fatigue and the temptation to rely on energy drinks for a quick energy boost. However, they may also be more attuned to the importance of proper rest, nutrition, and hydration in managing fatigue effectively.

A second point of attention is relative to professional responsibility. Healthcare personnel have a professional responsibility to promote health and well-being among their patients. As such, they may be more cautious about consuming energy drinks and advocate for healthier alternatives, given their knowledge of the potential risks. Health workers often serve as role models for their patients and the broader community. Their consumption habits, including their choices regarding energy drinks, can influence perceptions and behaviors among their peers and patients. Consequently, health workers may feel a heightened sense of responsibility to model healthy behaviors, including moderation in caffeine consumption.

-

The consumption of energizing beverages, particularly energy drinks, is on the rise among healthcare workers on night shifts. The pandemic has exacerbated stress levels and increased work shifts, fostering unhealthy lifestyle choices as coping mechanisms. Healthcare professionals, facing frequent and prolonged shifts during the pandemic, have turned to high-caffeine drinks to sustain their demanding schedules. While these drinks can enhance alertness and wakefulness, they also pose risks of acute and chronic health issues. In many cases, the consumption of energy drinks is perceived as safe, underestimating the synergistic effects of the various stimulants contained in the drinks. It is crucial to understand risk trajectories in healthcare workers and identify the motivations that lead to high stress to suggest effective methods to reduce both acute and chronic occupational stress.

However, health workers may approach energy drink consumption differently from other groups due to their unique knowledge, professional responsibilities, access to healthcare information, and commitment to ethical practice. They are more likely to consider the potential health implications and exercise caution when consuming energy drinks, recognizing the importance of maintaining their well-being to effectively care for others.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, methodology, writing - original draft preparation: Farinetti A, Coppi F, Mattioli AV; Writing - reviewing & editing: Salvioli B, Mattioli AV. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2024 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Farinetti A, Coppi F, Salvioli B, Mattioli AV. 2024. Night shifts and consumption of energy drinks by healthcare personnel. Beverage Plant Research 4: e033 doi: 10.48130/bpr-0024-0017

Night shifts and consumption of energy drinks by healthcare personnel

- Received: 26 January 2024

- Revised: 28 March 2024

- Accepted: 01 April 2024

- Published online: 05 September 2024

Abstract: The consumption of drinks with a high caffeine content is a growing phenomenon not only among young people but also among individuals who work night shifts, including healthcare workers. In young people, the motivations that lead to taking energy drinks are linked to performance in studies and recreational activities. In healthcare workers, the motivations are linked to work performance and the need to maintain a high level of wakefulness during the night. This review analyzes the studies published on the consumption of energy drinks in healthcare personnel and the changes that have occurred in recent years also following the stress caused by the recent pandemic on healthcare.

-

Key words:

- Night shifts /

- Healthcare workers /

- Energy drinks /

- Caffeine /

- Stress /

- Lifestyle