-

Cacao, Theobroma cacao L., is a cash crop native to the Amazon basin and widely used in chocolate production. Its demand steadily increases as global markets seek its rich and complex flavors. Cacao grows within 20° north and south of the equator, where both geography and climate are favorable. It is cultivated in over 50 countries[1], with an annual productivity of 4.8 million tons of cacao beans[2]. Globally, 40–50 million people depend on cacao for their livelihoods, but most cacao farmers live beneath the poverty line on an income of less than USD

${\$} $ The tropical Americas, particularly the center of origin of T. cacao, include key producers such as Brazil, Ecuador, Peru, Colombia, and Bolivia. These countries are recognized for producing fine and aromatic cacao, leveraging their unique genetic resources and environmental conditions. Among them, Peru is a country with a rich cacao heritage, cultivating over 177,350 hectares and producing 171,200 tons of cacao beans[6]. It is also the world's fourth largest producer of organic cacao, after Sierra Leone, the Dominican Republic, and the Democratic Republic of Congo[7].

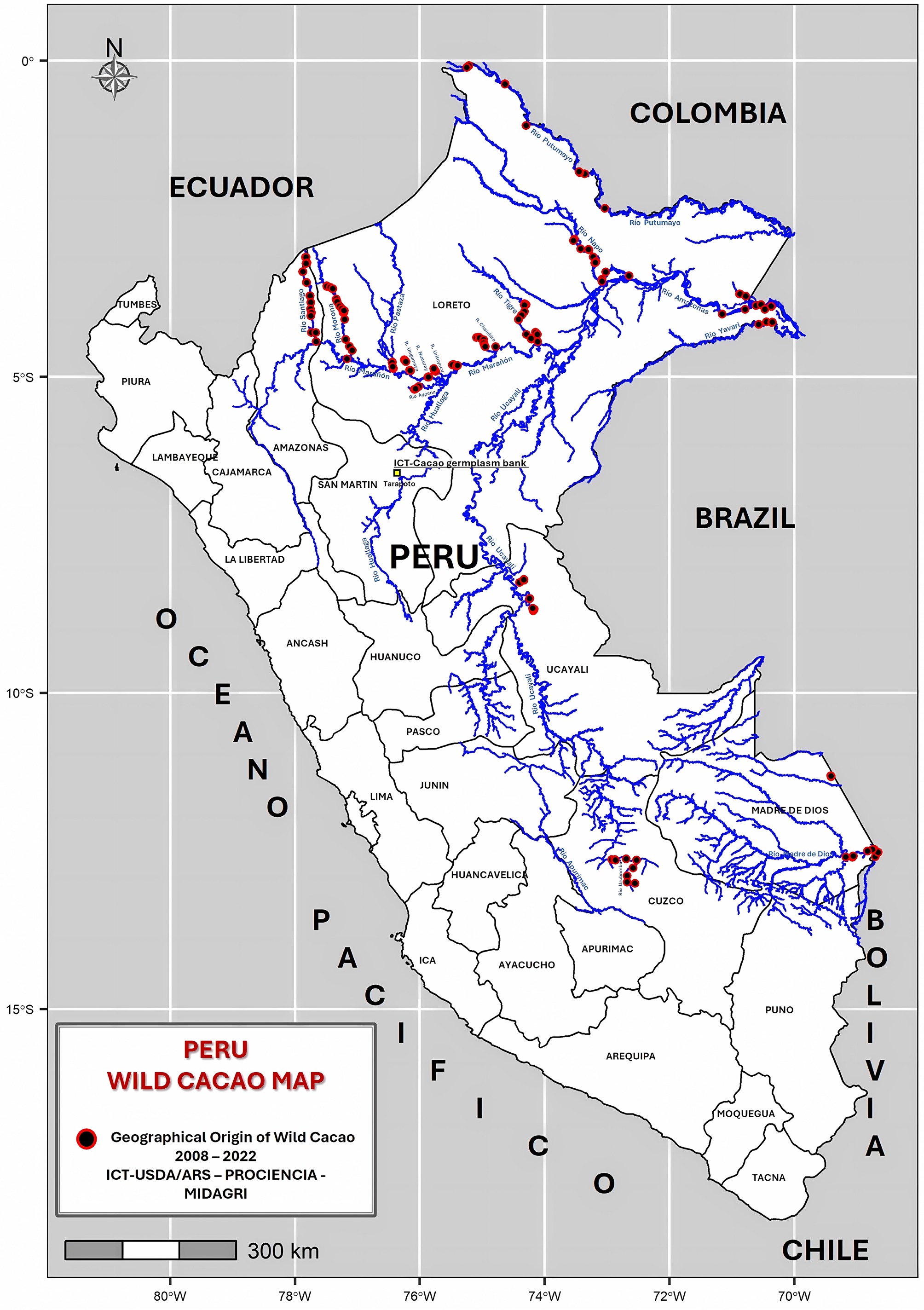

Peru is renowned for its rich biodiversity and for its numerous cacao landraces and wild populations, providing a unique opportunity for both the conservation of genetic resources and the development of improved cacao varieties. To preserve cacao genetic resources, expand the genetic base, and study cacao diversity, the Instituto de Cultivos Tropicales (Tropical Crops Institute, ICT) in Tarapoto, Peru, in collaboration with the USDA-ARS, Sustainable Perennial Crops Laboratory (USDA-ARS, SPCL) and INCAGRO-MINAGRI, has conducted collection expeditions since 2008 in the departments of Amazonas, Loreto, San Martín, Ucayali, Madre de Dios, and Cuzco[8−12]. A total of 540 wild cacao trees from 18 river basins were collected as budwood cuttings and propagated in the living GenBank of ICT[8,9,11]. This highlights the importance of characterizing these accessions for future breeding and productive diversification initiatives[13]. However, the genetic potential of cacao germplasm, particularly from the wild populations that spontaneously grow in the Amazon rainforest, remains poorly understood. Some reports highlighting the importance of this new wild cacao collection have been published[11]. For instance, accessions from the Santiago and Morona River basins were compared with the native cacao 'Piura Porcelana' to determine their identity and origin[8], highlighting the need for continued research, including studies on disease tolerance and their characterization[9,11].

Various studies have been conducted on wild cacao regarding genetic diversity, population structure, pests and disease resistance, and response to abiotic stress factors such as drought, acidic soils, and shade, among others[8,14−16]. Molecular characterization using single nucleotide polymorphisms and simple sequence repeat markers has revealed that this new cacao collection exhibits the highest genetic diversity and allele richness among all existing wild cacao collections[9,11]. This has led to the identification of new genetic groups of cacao[8,9].

Recent advancements in genomics have led to the sequencing of multiple cacao genomes, including wild cacao populations, providing valuable information on genetic diversity and trait associations[17−20]. By analyzing large datasets of genotypic and phenotypic information, cacao breeders can identify genomic regions associated with specific agronomic traits and practice Genome-Wide Association Studies and genomic prediction[21−24]. However, accurate phenotypic characterization is crucial because it provides the foundation for identifying genetic variants associated with specific traits. Without accurate phenotypic data, associating genetic variants with relevant traits lacks meaningful interpretation. Therefore, it is essential to integrate cutting-edge genomic and molecular studies with morphological characterization to facilitate the effective conservation of these unique accessions for the future production of fine aroma chocolates[25] and for cacao improvement[26].

Despite its crucial importance, phenotypic characterization had not previously been conducted on these new collections of wild cacao conserved in the ICT GenBank. Here, the first effort to morphologically characterize the 511 wild cacao accessions collected since 2008 from various basins in the Peruvian Amazonia was reported. The main objective of the study was to survey and analyze morphological variations in cacao plants, pods, and seed morphology in wild populations. The results contribute to understanding phenotypic diversity in wild cacao, support sustainable conservation, and accelerate the effective use of these wild cacao germplasms in breeding programs.

-

The wild cacao accessions collected between 2008 and 2015 are conserved at the germplasm bank located at the Choclino Experimental Station of ICT in Tarapoto, La Banda del Shilcayo District, San Martín Department, at 6.47° S, 76.33° W and 540 m above sea level. The trees from the different collections were planted in clay loam soil with a pH of 5.6, electrical conductivity of 4.3 mS/m, phosphorus content of 6.5 ppm, potassium content of 107.5 ppm, and organic matter content of 3.6%[27]. In the experimental area, the average annual rainfall is 1,250 mm, the average temperature is 26 °C, and the relative humidity is 87%[27].

Plant material

-

This study analyzed 511 georeferenced accessions from the departments of Amazonas (38 accessions), Cuzco (22 accessions), Loreto (362 accessions), Madre de Dios (55 accessions), and Ucayali (34 accessions) (Table 1; Fig. 1). The collected materials consisted of budwood, which was grafted onto four-month-old seedlings obtained from open-pollinated IMC-67 fruit seeds. After eight months, the grafted plants were planted at the germplasm bank.

Table 1. Accessions and location of collection of 511 wild cacao, planted and preserved at the germplasm bank of ICT in Tarapoto, Peru.

Department River basin, collection and planted year Range of geographical coordinates Altitude m.a.s.l. Accessions Latitude south Longitude west Loreto

(n = 282)Aypena (n = 22)

20085.15322°−5.19753° 76.01758°−76.08981° 120−133 AYP-1, AYP-2, AYP-3, AYP-4, AYP-5, AYP-6, AYP-7, AYP-8, AYP-9, AYP-10, AYP-11, AYP-12, AYP-13, AYP-14, AYP-15, AYP-16, AYP-17, AYP-18, AYP-19, AYP-20, AYP-21, AYP-22 Marañón (n = 22)

20085.00139°−5.00222° 75.85292°−75.85792° 124−139 MACH-23, MACH-24, MACH-25, MACH-26, MACH-27, MACH-28, MACH-29, MACH-30, MACH-31, MACH-32, MACH-33, MACH-34, MACH-35, MACH-36, MACH-37, MACH-38, MACH-39, MACH-40, MACH-41, MACH-42, MACH-43, MACH-44 Ungurahui (n = 38)

20084.76397°−4.77833° 76.44006°−76.44311° 127−144 UNG-45, UNG-46, UNG-47, UNG-48, UNG-49, UNG-50, UNG-51, UNG-52, UNG-53, UNG-54, UNG-55, UNG-56, UNG-57, UNG-58, UNG-59, UNG-60, UNG-61, UNG-62, UNG-63, UNG-64, UNG-65, UNG-66, UNG-67, UNG-68, UNG-69, UNG-70, UNG-71, UNG-72, UNG-73, UNG-74, UNG-75, UNG-76, UNG-77, UNG-78, UNG-79, UNG-80, UNG-81, UNG-82 Pastaza (n = 24)

20084.83819°−4.86897° 76.42342°−76.43353° 129−140 PAS-83, PAS-84, PAS-85, PAS-86, PAS-87, PAS-88, PAS-89, PAS-90, PAS-91, PAS-92, PAS-93, PAS-94, PAS-95, PAS-96, PAS-97, PAS-98, PAS-99, PAS-100, PAS-101, PAS-102, PAS-103, PAS-104, PAS-105, PAS-106 Ungumayo (n = 26)

20084.73297°−4.90708° 76.14847°−76.24644° 127−141 UGU-107, UGU-108, UGU-109, UGU-110, UGU-111, UGU-112, UGU-113, UGU-114, UGU-115, UGU-116, UGU-117, UGU-118, UGU-119, UGU-120, UGU-121, UGU-122, UGU-123, UGU-124, UGU-125, UGU-126, UGU-127, UGU-128, UGU-129, UGU-130, UGU-131, UGU-132 Nucuray (n = 25)

20084.86900°−4.91703° 75.74594°−75.77547° 115−131 NUC-133, NUC-134, NUC-135, NUC-136, NUC-137, NUC-138, NUC-139, NUC-140, NUC-141, NUC-142, NUC-143, NUC-144, NUC-145, NUC-146, NUC-147, NUC-148, NUC-149, NUC-150, NUC-151, NUC-152, NUC-153, NUC-154, NUC-155, NUC-156, NUC-157 Urituyacu (n = 33)

20084.80644°−4.83300° 75.39525°−75.47986° 97−130 URI-158, URI-159, URI-160, URI-161, URI-162, URI-163, URI-164, URI-165, URI-166, URI-167, URI-168, URI-169, URI-170, URI-171, URI-172, URI-173, URI-174, URI-175, URI-176, URI-177, URI-178, URI-179, URI-180, URI-181, URI-182, URI-183, URI-184, URI-185, URI-186, URI-187, URI-188, URI-189, URI-190 Morona (N = 50)

20093.56269°−4.71822° 77.08089°−77.49225° 136−196 MOR-192, MOR-194, MOR-196, MOR-198, MOR-200, MOR-202, MOR-204, MOR-206, MOR-208, MOR-210, MOR-212, MOR-214, MOR-216, MOR-218, MOR-220, MOR-222, MOR-224, MOR-226, MOR-228, MOR-230, MOR-232, MOR-234, MOR-236, MOR-238, MOR-240, MOR-242, MOR 244, MOR-246, MOR-248, MOR-250, MOR-252, MOR-254, MOR-256, MOR-258, MOR-260, MOR-262, MOR 264, MOR-266, MOR-268, MOR-270, MOR-272, MOR-274, MOR-276, MOR-278, MOR-280, MOR-282, MOR-284, MOR-286, MOR-288, MOR-290 Chambira (n = 20)

20134.29673°−4.52512° 74.11835°−75.09407° 113−118 CH-267, CH-269, CH-271, CH-273, CH-275, CH-277, CH-279, CH-281, CH-283, CH-285, CH-287, CH-289, CH-291, CH-292, CH-293, CH-294, CH-295, CH-296, CH-297, CH-298 Tigre (n = 22)

20133.84153°−4.44577° 74.11407°−74.41777° 99−125 TIG-299, TIG-300, TIG-301, TIG-302, TIG-303, TIG-304, TIG-305, TIG-306, TIG-307, TIG-308, TIG-309, TIG-310, TIG-311, TIG-312, TIG-313, TIG-314, TIG-315, TIG-316, TIG-317, TIG-318, TIG-319, TIG-320 Loreto

(n = 80)Napo (n = 22)

20132.81950°−3.48998° 72.64783°−73.53973° 92−104 NAP-321, NAP-322, NAP-323, NAP-324, NAP-325, NAP-326, NAP-327, NAP-328, NAP-329, NAP-330, NAP-331, NAP-332, NAP-333, NAP-334, NAP-335, NAP-336, NAP-337, NAP-338, NAP-339, NAP-340, NAP-341, NAP-342 Putumayo (n = 18)

20150.07867°−2.33301° 73.03614°−75.24604° 40−222 PUT(A)-460, PUT(B)-460, PUT-462, PUT-464, PUT-466, PUT-466(A), PUT-466(B), PUT-468, PUT-468(A), PUT-470, PUT-472, PUT-474, PUT-476, PUT-478, PUT-480, PUT-482, PUT-484, PUT-486 Yavari (n = 23)

20153.88507°−4.17261 70.35288°−70.57453° 91−101 YAV-435, YAV-437, YAV-439, YAV- 441, YAV-443, YAV-445, YAV-447, YAV-449, YAV-451, YAV-453, YAV-455, YAV-457, YAV-459, YAV-461, YAV-463, YAV-465, YAV-467, YAV-469, YAV-471, YAV-473, YAV-475, YAV-477, YAV-479 Amazonas (n = 17)

20153.85979°−4.00796° 70.53532°−71.15834° 77−101 AMZ-436, AMZ-438, AMZ-440, AMZ-442, AMZ-446, AMZ-448, AMZ-452, AMZ-454, AMZ-456, AMZ-481, AMZ-483, AMZ-485, AMZ-487, AMZ-489, AMZ-491, AMZ-493, AMZ-495 Amazonas

(n = 38)Santiago(n = 38)

20093.10756°−4.44411° 77.56778°−77.87917° 148−252 SAN-191, SAN-193, SAN-195, SAN-197, SAN-199, SAN-201, SAN-203, SAN-205, SAN-207, SAN-209, SAN-211, SAN-213, SAN-215, SAN-217, SAN-219, SAN-221, SAN-223, SAN-225, SAN-227, SAN-229, SAN-231, SAN-233, SAN-235, SAN-237, SAN-239, SAN-241, SAN-243, SAN-245, SAN-247, SAN-249, SAN-251, SAN-253, SAN-255, SAN-257, SAN-259, SAN-261, SAN-263, SAN-265 Cuzco

(n = 22)Urubamba

(n = 22) 201012.62803°−13.01153° 72.53150°−72.92381° 665−1,478 CHUN-1, CHUN-2, CHUN-3, CHUN-4, CHUN-5, CHUN-6, CHUN-7, CHUN-8, CHUN-9, CHUN-10, CHUN-11, CHUN-12, CHUN-13, CHUN-14, CHUN-15, CHUN-16, CHUN-17, CHUN-18, CHUN-19, CHUN-20, CHUN-21, CHUN-22 Madre de Dios

(n = 55)Madre de Dios

(n = 55) 201011.31142°−12.60000° 68.65986°−69.41619° 171−316 PPA-346, PPA-347, PPA-348, PPA-349, PPA-350, PPA-351, PPA-352, PPA-353, PPA-354, PPA-355, PPA-356, PPA-357, HIT-358, HIT-359, HIT-360, HIT-361, HIT-362, HIT-363, HIT-364, PPR-365, PPR-366, PPR-367, PPR-368, PPR-369, SFR-370, SFR-371, SFR-372, SFR-373, SFR-374, SFR-375, SFR-376, SFR-377, SFR-378, SND-379, SND-380, SND-381, SND-382, SND-383, SND-384, SND-385, ROL-385, ROL-386, ROL-386, ROL-387, ROL-388, ROL-389, ARR-390, ARR-391, ARR-392, ARR-393, ARR-394, ARR-395, ARR-396, ARR-397, ARR-398, ARR-399, ARR-400 Ucayali

(n = 34)Ucayali (n = 34)

20108.20719°−8.69872° 74.16783°−74.40353° 153−164 TAM-401, TAM-402, TAM-403, TAM-404, TAM-405, TAM-406, TAM-407, TAM-408, TAM-409, TAM-410, TAM-411, TAM-412, TAM-413, TAM-414, TAM-415, TAM-416, TAM-417, ABJ-418, ABJ-419, ABJ-420, ABJ-421, ABJ-422, UTQ-423, UTQ-424, UTQ-425, UTQ-426, UTQ-427, UTQ-428, UTQ-429, UTQ-430, UTQ-431, UTQ-432, UTQ-433, UTQ-434 Plant distribution in germplasm bank

-

In the germplasm bank, each accession of wild cacao consisted of five plants established at 1.5 m × 2 m in a triangular layout. Characterization was conducted on plants aged six to twelve years (Table 1), from 2020 to 2021.

Quantitative morphological descriptors

-

The descriptors used to characterize the 511 wild cacao trees were considered under the methodology of García[28], Phillips-Mora et al.[29], Restrepo and Urrego[30], López et al.[31], and Vásquez-García[32], which considered leaf, fruit, seeds, and flower descriptors. This study considered 27 quantitative traits: four for leaves, nine for fruits, five for seeds, and nine for flowers (Table 2).

Table 2. Agro-morphological descriptors considered in this study.

N° Descriptor Leaf 1 Length (LL) and width (WL) of the leaf in centimeters 2 Length from base to the most comprehensive point of a leaf (LBL) in centimeters 3 Petiole length (PL) in centimeters Fruit 4 Fruit weight (FW) in grams 5 Seed fresh weight (SFW) and Seed dry weight (SDW) 6 Length (FL) and diameter (FD) of fruits in centimeters 7 Length (FL)/diameter (FD) ratio (FL/FD) 8 Husk thickness (HusT) in centimeters 9 Furrow depth (FwD) in centimeters 10 Pod index (PI) [1,000/SDW] Seed 11 Seed number per fruit (SeN) 12 Seed index (SI) [SDW/SeN] 13 Length (SeL) and width (SeW) of the seeds in millimeters 14 Seed thickness (SeT) in millimeters Flower 15 Length (SepL) and width (SepW) of the sepal in millimeters 16 Length (PeL) and width (PeW) of the petal in millimeters 17 Staminodium length (StL) in millimeters 18 Length (OvL) and width (OvW) of the ovary in millimeters 19 Style Length (StyL) in millimeters 20 Number of ovules per ovary (Ov/o) Five leaves with good status were collected from each genotype at the fifth node of the branches at chest height on the tree. All variables were measured using a ruler. Five fruits in mature condition per plant were collected to evaluate the traits described in Table 2; the seeds were extracted from the fruits, and ten seeds were randomly selected to measure the traits listed in Table 2. All fruit and seed measurements were made with a digital vernier caliper. Ten flowers were collected from each genotype to measure their characteristics by using a stereoscopy EUROMEX NZ.1703-P stereoscope. The data were collected during the same season to minimize environmental variability.

Statistical analysis

-

Multivariate techniques were used to analyze the data. The variables that significantly contributed to forming groups were determined first by Spearman correlation and principal components PCA. From among the 27 variables, eight variables were selected based on their significant contributions to explaining the variability among accessions and for the posterior analysis. Cluster analysis of the traits for groups of wild cacao with similar characteristics was performed using Ward's method and Gower distance. Subsequently, variance analysis was performed by groups, followed by the Scott & Knott mean comparison test (p ≤ 0.05) for each group. Additionally, a discriminant analysis was performed using InfoStat version 2020[33] to identify the significant quantitative variables influencing group formation.

-

The overall descriptive statistics for the 511 wild cacao accessions, based on 27 quantitative traits, are presented in Table 3. The coefficient of variability (CV) associated with each trait was greater than 10%, indicating significant phenotypic diversity among the wild cacao accessions conserved in the ICT Genbank. Furrow depth exhibited the highest variability (CV = 33.02%), whereas seed width showed the lowest variability (CV = 10.56%).

Table 3. Minimum (min), maximum (max), mean values ± standard deviation (SD), and statistical significance (p ≤ 0.05) for 27 leaf, fruit, seed, and flower descriptors of 511 accessions of wild cacao from the Peruvian Amazonia.

Variables* Min Max Mean ± SD CV % F p-value LL (cm) 23.54 34.4 28.78 ± 3.92 13.63 1.13 0.03871 LW (cm) 6.88 13.36 9.89 ± 2.10 21.18 1.19 0.00507 LBL (cm) 11.52 20.52 14.65 ± 2.57 17.53 1.20 0.00329 PL (cm) 1.26 4.94 1.81 ± 0.53 29.39 1.46 < 0.0001 FW (g) 348.34 763.27 568.25 ± 179.64 31.61 0.95 0.7533 SFW (g) 62.54 166.13 100.7 ± 30.55 30.34 1.42 < 0.0001 SDW (g) 24.37 63.2 36.75 ± 10.65 28.99 1.50 < 0.0001 FL (cm) 15.04 22.36 18.78 ± 2.05 10.94 1.68 < 0.0001 FD (cm) 6.72 14.25 11.36 ± 2.06 18.17 3.86 < 0.0001 FL/FD 1.24 2.9 1.71 ± 0.39 22.70 2.99 < 0.0001 FwD (mm) 5.5 16.93 8.3 ± 2.74 33.02 2.88 < 0.0001 HusT (mm) 10.13 21.3 15.49 ± 3.70 23.86 3.20 < 0.0001 SeN (n) 21.2 46.8 33.09 ± 7.59 22.93 1.15 0.02259 SI (g) 0.8 1.64 1.13 ± 0.26 23.34 1.80 < 0.0001 PI (n) 16.4 43.6 29.67 ± 8.32 28.03 1.41 < 0.0001 SeL (mm) 16.99 26.54 21.57 ± 2.78 12.89 3.45 < 0.0001 SeW (mm) 10.2 15.45 12.53 ± 1.32 10.56 3.74 < 0.0001 SeT (mm) 5.99 12.02 9.3 ± 1.58 16.95 2.25 < 0.0001 SepL (mm) 4.88 9.5 7.21 ± 1.19 16.45 1.74 < 0.0001 SepW (mm) 1.44 2.97 2.14 ± 0.45 21.02 1.74 < 0.0001 PeL (mm) 3 6.44 4.52 ± 0.80 17.78 6.48 < 0.0001 PeW (mm) 1.24 2.8 1.93 ± 0.41 21.39 4.52 < 0.0001 StL (mm) 3.76 7.04 5.19 ± 0.68 13.16 2.86 < 0.0001 OvL (mm) 1.16 2.28 1.68 ± 0.32 18.92 2.33 < 0.0001 OvW (mm) 0.72 1.6 1.16 ± 0.28 23.71 2.88 < 0.0001 StyL (mm) 1.3 2.98 2.31 ± 0.36 15.76 2.97 < 0.0001 Ov/o (n) 22.4 47.4 35.59 ± 7.35 20.65 4.89 < 0.0001 * Leaf traits: Leaf length (LL), Leaf width (LW), Length from base to widest point of a leaf (LBL), Petiole length (PL). Fruit traits: Fruit weight (FW), Fruit length (FL), Fruit diameter (FD), Fruit length-to-diameter ratio (FL/FD), Furrow depth (FwD), Husk thickness (HusT), Pod index (PI). Seed traits: Seed fresh weight (SFW), Seed dry weight (SDW), Seed number per fruit (SeN), Seed index (SI), Seed length (SeL), Seed width (SeW), Seed thickness (SeT). Floral traits: Sepal length (SepL), Sepal width (SepW), Petal length (PeL), Petal width (PeW), Staminate length (StL), Ovary length (OvL), Ovary width (OvW), Style length (StyL), Ovules per ovary (Ov/o). CV = coefficient of variability; F and p-value determined from analysis of variance. Analysis of variance for 27 quantitative traits detected significant (p ≤ 0.05) differences among the 511 wild cacao accessions for all traits considered except fruit weight (p = 0.7533) (Table 3). This indicated the broader variation of the accessions in the studied traits. Seed index and Pod index, traits considered indicators of the yield potential, varied from 0.8 to 1.64 g and 16.4 to 43.6 fruits/kg, respectively (Table 3).

Characterization of wild cacao by river basin

-

All means of the quantitative agronomic traits, except for leaf length, petiole length, and fruit weight, showed significant variation among the river basins (Table 4). The coefficient of variation (CV) across river basins was greater than 10% for petiole length, fruit weight, seed fresh weight, seed dry weight, furrow depth, seed number per fruit, seed index, and pod index, whereas the other traits exhibited lower CV values. This suggests significant phenotypic diversity among the different river basins for the agronomic traits of wild cacao. Petiole length had the highest variability (CV = 15.15%), while seed width had the lowest (CV = 4.07%).

Table 4. Means for 27 leaf, fruit, seed, and flower descriptors of 511 accessions of wild cacao by river basin in peruvian amazonia. CV = coefficient of variability; F and p-value determined from analysis of variance.

Traits** River basin* AMZ AYP CHA MDD MAR MOR NAP NUC PAS PUT SAN TIG UCA UGU UNG URI URU YAV CV % F p-value LL (cm) 28.68 28.36 28.66 29.14 28.34 28.82 29.15 27.85 28.77 28.12 28.85 28.97 29.25 29.59 28.47 29.01 28.77 28.34 6.34 1.47 0.0986 LW (cm) 9.86 b 10.38 a 10.10 a 9.62 b 9.61 b 9.71 b 10.05 a 10.10 a 10.46 a 9.94 a 9.86 b 9.73 b 9.97 a 10.19 a 9.76 b 9.64 b 9.49 b 10.33 a 9.95 2.22 0.0034 LBL (cm) 14.36 b 15.01 a 14.71 b 14.28 b 14.34 b 14.45 b 14.66 b 15.06 a 15.31 a 14.54 b 14.47 b 14.29 b 14.58 b 15.52 a 14.73 b 14.94 a 14.18 b 14.66 b 8.22 2.53 0.0007 PL (cm) 1.66 1.93 1.85 1.78 1.84 1.79 1.74 1.82 1.86 1.81 1.80 1.79 1.81 1.82 1.92 1.80 1.75 1.81 15.15 1.18 0.2788 FW (g) 559.39 549.79 587.93 557.59 583.63 576.50 573.22 587.79 561.59 567.38 565.02 565.05 574.11 568.96 564.30 561.19 558.57 574.62 13.99 0.46 0.9684 SFW (g) 110.12 a 94.07 c 105.33 b 117.48 a 99.64 b 89.6 d 100.55 b 83.52 d 90.63 d 103.26 b 103.49 b 102.56 b 105.15 b 101.53 b 101.89 b 95.92 c 95.51 c 104.47 b 13.21 12.40 <0.0001 SDW (g) 39.88 b 34.12 c 38.26 b 42.98 a 36.20 b 32.85 d 36.62 b 30.60 d 33.17 d 37.72 b 37.60 b 37.55 b 38.27 b 36.96 b 37.33 b 35.16 c 34.80 c 38.1 b 12.81 12.95 <0.0001 FL (cm) 19.07 a 18.93 a 17.27 b 19.11 a 18.84 a 18.65 a 19.19 a 18.85 a 19.16 a 19.08 a 16.85 b 19.01 a 19.22 a 18.65 a 19.11 a 18.96 a 19.18 a 19.30 a 4.84 16.28 <0.0001 FD (cm) 12.15 a 12.33 a 11.78 a 11.91 a 12.06 a 8.94 b 12.03 a 11.93 a 12.04 a 12.04 a 9.21 b 12.15 a 12.01 a 12.08 a 12.01 a 12.08 a 11.66 a 8.93 b 6.74 78.11 <0.0001 FL/FD 1.60 c 1.56 c 1.50 c 1.64 c 1.60 c 2.17 a 1.63 c 1.61 c 1.62 c 1.62 c 1.87 b 1.59 c 1.63 c 1.58 c 1.63 c 1.60 c 1.68 c 2.17 a 9.04 51.99 <0.0001 FwD (mm) 7.31 d 8.26 c 7.46 d 7.58 d 7.98 c 11.88 a 7.88 c 8.43 c 7.93 c 7.32 d 10.30 b 7.66 d 7.23 d 8.20 c 7.83 c 7.90 c 6.62 e 7.50 d 13.16 50.06 <0.0001 HusT (mm) 13.68 d 17.36 b 13.5 d 13.8 d 16.85 b 18.09 a 13.44 d 17.24 b 17.5 b 13.08 d 15.44 c 13.63 d 13.83 d 17.34 b 17.59 b 17.51 b 11.38 e 13.45 d 8.96 65.67 <0.0001 SeN (n) 31.98 c 32.69 c 31.69 c 34.69 b 33.09 c 32.70 c 31.8 c 33.34 c 33.00 c 33.51 c 32.72 c 31.38 c 34.32 b 32.58 c 33.33 c 31.33 c 36.67 a 33.02 c 10.34 3.86 <0.0001 SI (g) 1.25 a 1.05 c 1.22 a 1.25 a 1.10 b 1.01 c 1.16 b 0.92 d 1.01 c 1.15 b 1.17 b 1.22 a 1.14 b 1.15 b 1.14 b 1.15 b 0.95 d 1.19 b 10.10 20.76 <0.0001 PI (n) 27.84 c 31.85 b 28.77 c 26.20 d 29.93 c 31.98 b 29.65 c 34.18 a 32.13 b 28.47 c 28.58 c 28.34 c 28.16 c 29.00 c 28.64 c 30.21 c 34.61 a 28.51 c 12.36 11.28 <0.0001 SeL (mm) 20.57 c 23.94 a 20.34 c 20.41 c 23.17 a 20.09 c 20.70 c 23.69 a 23.56 a 20.53 c 21.41 b 20.64 c 20.62 c 23.54 a 23.32 a 23.63 a 18.35 d 20.41 c 4.70 75.80 <0.0001 SeW (mm) 12.32 b 13.30 a 12.46 b 12.35 b 13.33 a 11.05 d 12.6 b 13.30 a 13.30 a 12.53 b 11.86 c 12.43 b 12.43 b 13.35 a 13.29 a 13.40 a 10.99 d 12.45 b 4.07 68.65 <0.0001 SeT (mm) 8.98 c 9.97 a 8.74 c 9.12 c 9.67 b 9.04 c 8.79 c 10.13 a 10.05 a 9.15 c 9.08 c 8.97 c 8.93 c 10.08 a 10.09 a 10.29 a 6.74 d 8.96 c 6.23 50.91 <0.0001 SepL (mm) 7.23 c 8.00 a 7.95 a 7.66 b 6.32 e 7.19 c 7.20 c 7.25 c 7.10 c 7.19 c 7.04 c 7.25 c 6.88 d 7.02 c 7.03 c 6.83 d 7.84 a 6.85 d 7.40 16.06 <0.0001 SepW (mm) 2.17 b 2.73 a 2.23 b 2.21 b 2.03 c 2.27 b 2.07 c 2.29 b 2.09 c 2.07 c 1.94 d 2.02 c 2.06 c 1.98 d 2.04 c 2.06 c 2.25 b 1.98 d 8.69 24.26 <0.0001 PeL (mm) 4.24 e 6.01 a 4.15 f 4.11 f 5.05 c 4.69 d 4.20 e 5.37 b 5.34 b 4.20 e 4.33 e 4.12 f 4.10 f 5.09 c 5.04 c 4.08 f 3.38 g 4.16 f 5.33 177.84 <0.0001 PeW (mm) 1.79 f 2.69 a 1.70 g 1.75 f 2.00 e 2.07 d 1.79 f 2.26 c 2.06 d 1.67 g 1.97 e 1.70 g 1.72 g 2.45 b 1.93 e 1.78 f 1.66 g 1.72 g 7.95 86.33 <0.0001 StL (mm) 5.18 d 5.78 b 5.07 e 5.29 d 5.20 d 5.01 e 5.16 d 5.49 c 5.54 c 5.22 d 4.39 f 5.18 d 5.25 d 5.00 e 5.00 e 5.11 e 5.99 a 5.23 d 5.69 37.92 <0.0001 OvL (mm) 1.72 c 1.91 a 1.68 c 1.71 c 1.78 b 1.82 b 1.76 c 1.80 b 1.75 c 1.69 c 1.41 e 1.73 c 1.75 c 1.29 f 1.54 d 1.72 c 1.57 d 1.70 c 7.57 40.05 <0.0001 OvW (mm) 1.29 a 1.03 d 1.27 b 1.25 b 0.89 f 1.30 a 1.33 a 0.97 e 1.03 d 1.30 a 0.98 e 1.27 b 1.29 a 1.02 d 1.00 d 1.24 b 1.11 c 1.33 a 9.15 55.53 <0.0001 StyL (mm) 2.23 c 2.73 a 2.25 c 2.22 c 2.20 d 2.26 c 2.24 c 2.67 a 2.52 b 2.29 c 2.15 d 2.23 c 2.27 c 2.31 c 2.65 a 2.24 c 1.90 e 2.26 c 6.17 54.36 <0.0001 Ov/o (n) 39.19 c 32.08 e 38.13 c 38.31 c 29.78 f 42.68 a 37.70 c 30.02 f 33.22 e 39.40 c 41.01 b 37.7 c 37.96 c 27.06 h 28.54 g 29.44 f 35.32 d 37.05 c 7.06 112.25 <0.0001 * AMZ = Amazonas, AYP = Aypena, CHA = Chambira, MDD = Madre de Dios, MAR = Marañón, MOR = Morona, NAP = Napo, NUC = Nucuray, PAS = Pastaza, PUT = Putumayo, SAN = Santiago, TIG = Tigre, UCA = Ucayali, UGU = Ungumayo, UNG = Ungurahui, URI = Urituyacu, YAV = Yavarí. Means with identical letters in rows are not significantly different. ** Leaf traits: Leaf length (LL), Leaf width (LW), Length from base to the widest point of a leaf (LBL), Petiole length (PL). Fruit traits: Fruit weight (FW), Fruit length (FL), Fruit diameter (FD), Fruit length-to-diameter ratio (FL/FD), Furrow depth (FwD), Husk thickness (HusT), Pod index (PI). Seed traits: Seed fresh weight (SFW), Seed dry weight (SDW), Seed number per fruit (SeN), Seed index (SI), Seed length (SeL), Seed width (SeW), Seed thickness (SeT). Floral traits: Sepal length (SepL), Sepal width (SepW), Petal length (PeL), Petal width (PeW), Staminate length (StL), Ovary length (OvL), Ovary width (OvW), Style length (StyL), Ovules per ovary (Ov/o). The cacao accessions with the minimum and maximum mean values for the 27 agronomic traits are shown in Table 5. The lowest and highest values for each trait were from the following river basins:

Table 5. Cacao accessions with minimum and maximum values for 27 leaf, fruit, seed, and flower descriptors.

Traits* Minimum value Maximum value LL (cm) AYP 10 = 23.54 UGU 114 = 34.4 LW (cm) UNG 64 = 6.88 AYP 22 = 13.36 LBL (cm) SAN 199 = 11.52 AYP 2 = 20.52 PL (cm) AMZ 452 = 1.26 AYP 7 = 4.94 FW (g) URI 165 = 348.34 TIG 307 = 763.27 SFW (g) NAP 328 = 62.54 ARR 400 = 166.13 SDW (g) NAP 328 = 24.37 ARR 400 = 63.2 FL (cm) SAN 235 = 15.04 MOR 212 = 22.36 FD (cm) MOR 220 = 6.72 PUT 476 = 14.25 FL/FD CHA 295 = 1.24 MOR 212 = 2.9 FwD (mm) ABI 418 = 5.5 MOR 216 = 16.93 HusT (mm) CHUN 5 = 10.13 UNG 50 = 21.3 SeN (n) CHA 291 = 21.2 ARR 400 = 46.8 SI (g) CHUN 12 = 0.8 AMZ 446 = 1.64 PI (n) ARR 400 = 16.4 YAV 459 = 43.6 SeL (mm) CHUN 15 = 16.99 UNG 55 = 26.54 SeW (mm) MOR 204 = 10.2 PAS 96 = 15.45 SeT (mm) CHUN 6 = 5.99 URI 178 = 12.02 SepL (mm) YAV 437 = 4.88 CHUN 9 = 9.5 SepW (mm) PUT 460A, YAV 437 = 1.44 AYP 8 = 2.97 PeL (mm) CHUN 16 = 3 AYP 1 = 6.44 PeW (mm) TAM 415 = 1.24 AYP 9, AYP 19 = 2.8 StL (mm) SAN 233 = 3.76 CHUN 4 = 7.04 OvL (mm) SAN 259 = 1.16 MOR 226 = 2.28 OvW (mm) CHUN 11 = 0.72 UTQ 423, YAV 475 = 1.6 StyL (mm) CHUN 8 = 1.3 UNG 63 = 2.98 Ov/o (n) UGU 129 = 22.4 MOR 248 = 47.4 * Leaf traits: Leaf length (LL), Leaf width (LW), Length from base to the widest point of a leaf (LBL), Petiole length (PL). Fruit traits: Fruit weight (FW), Fruit length (FL), Fruit diameter (FD), Fruit length-to-diameter ratio (FL/FD), Furrow depth (FwD), Husk thickness (HusT), Pod index (PI). Seed traits: Seed fresh weight (SFW), Seed dry weight (SDW), Seed number per fruit (SeN), Seed index (SI), Seed length (SeL), Seed width (SeW), Seed thickness (SeT). Floral traits: Sepal length (SepL), Sepal width (SepW), Petal length (PeL), Petal width (PeW), Staminate length (StL), Ovary length (OvL), Ovary width (OvW), Style length (StyL), Ovules per ovary (Ov/o). Amazonas: Lowest petiole length; highest seed index.

Aypena: Lowest leaf length; highest leaf width, length from base to the widest point of a leaf, petiole length, sepal width, petal length, and petal width.

Chambira: Lowest fruit length-to-diameter ratio and seed number per fruit.

Madre de Dios: Lowest pod index; highest seed fresh weight, seed dry weight, and seed number per fruit.

Morona: Lowest fruit diameter and seed width; highest fruit length, fruit length-to-diameter ratio, furrow depth, ovary length, and ovules per ovary.

Napo: Lowest seed fresh weight and seed dry weight.

Pastaza: Highest seed width.

Putumayo: Lowest sepal width; highest fruit diameter.

Santiago: Lowest length from base to the widest point of a leaf, fruit length, staminate length, and ovary length.

Tigre: Highest fruit weight.

Ucayali: Lowest furrow depth and petal width; highest ovary width.

Ungumayo: Lowest ovules per ovary; highest leaf length.

Ungurahui: Lowest leaf width and length from base to the widest point of a leaf; highest husk thickness, seed length, and style length.

Urituyacu: Lowest fruit weight; highest seed thickness.

Urubamba: Lowest husk thickness, seed index, seed length, seed thickness, petal length, ovary width, and style length; highest sepal length and staminate length.

Yavarí: Lowest sepal length and sepal width; highest pod index and ovary width.

Only three accessions had a seed index greater than 1.5 g: Amazonas (AMZ 446 = 1.64 g); Madre de Dios (PPR 365 = 1.56 g); and Tigre (TIG 315 = 1.53 g. The pod index ranged from 16.4 to 43.6, with 1.8% of wild cacao accessions less than 21, including Amazonas (AMZ 446 = 19.4), Chambira (CHA 297 = 20.8), Madre de Dios (ARR 400 = 16.4, PPA 354 = 19.6, PPR 365 = 19.2, RL 389 = 21, SFR 377 = 20, SND 383 = 21), and Tigre (TIG 303 = 21).

Characterization of groups of clones within the germplasm

-

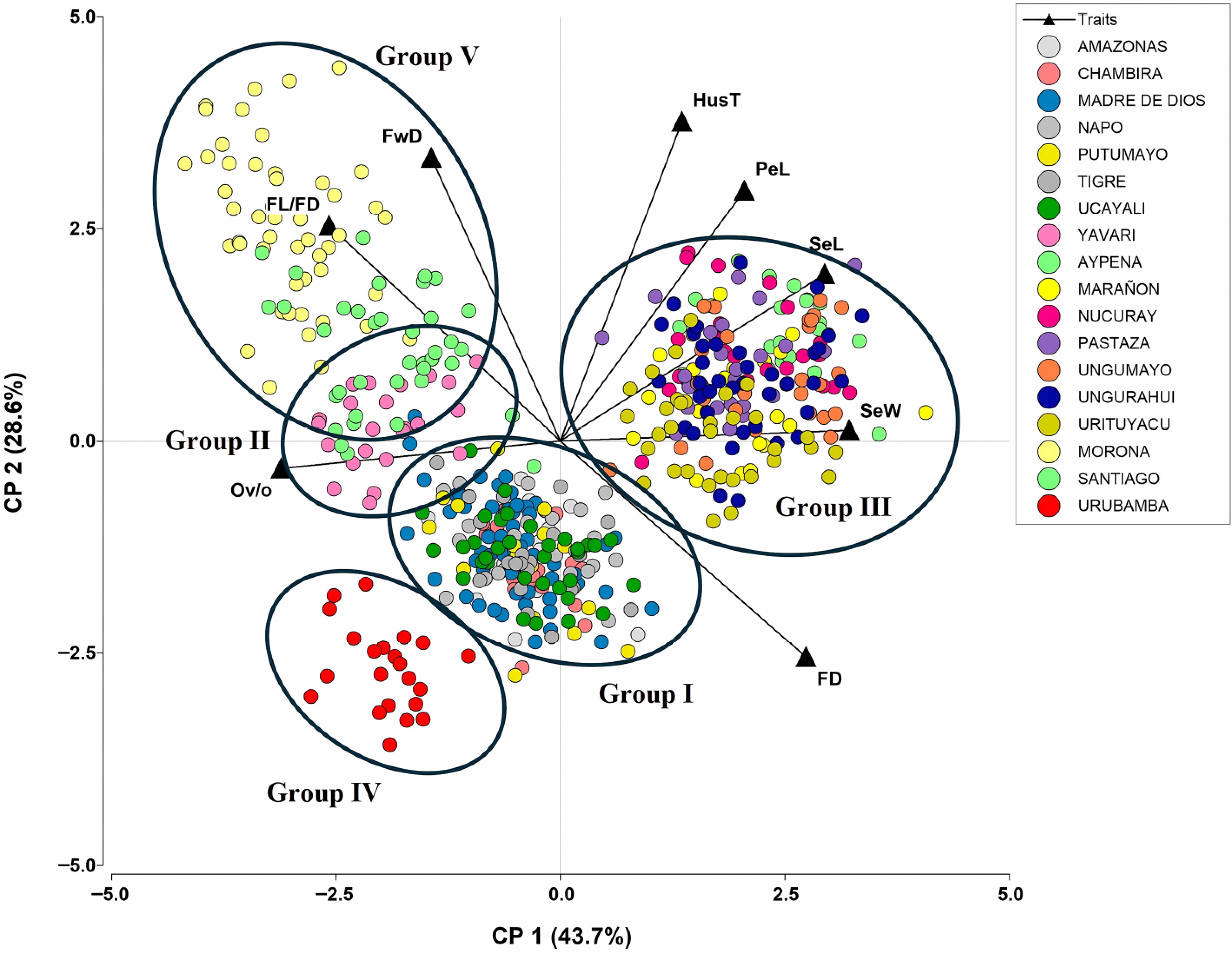

Principal component analysis first identified the variables that significantly contributed to group formation. The traits with the highest correlation that contributed significantly to diversification were fruit diameter, fruit length-to-diameter ratio, furrow depth, husk thickness, seed length, seed width, petal length, and ovules per ovary (Fig. 2). These descriptors explained 72.3% of the phenotypic quantitative variability of the wild cacao accessions used to form the groups. The first axis explains 43.7% of the variability, dividing all wild cacao into two large groups: 281 wild accessions (55%) associated with furrow depth, fruit length-to-diameter ratio, and ovules per ovary, and 230 wild accessions (45%) associated with husk thickness, petal length, seed length, seed width, and fruit diameter.

Figure 2.

Biplot resulting from the principal components analysis based on quantitative traits with the most contribution to the phenotypic diversity of cacao in Peruvian river basins.

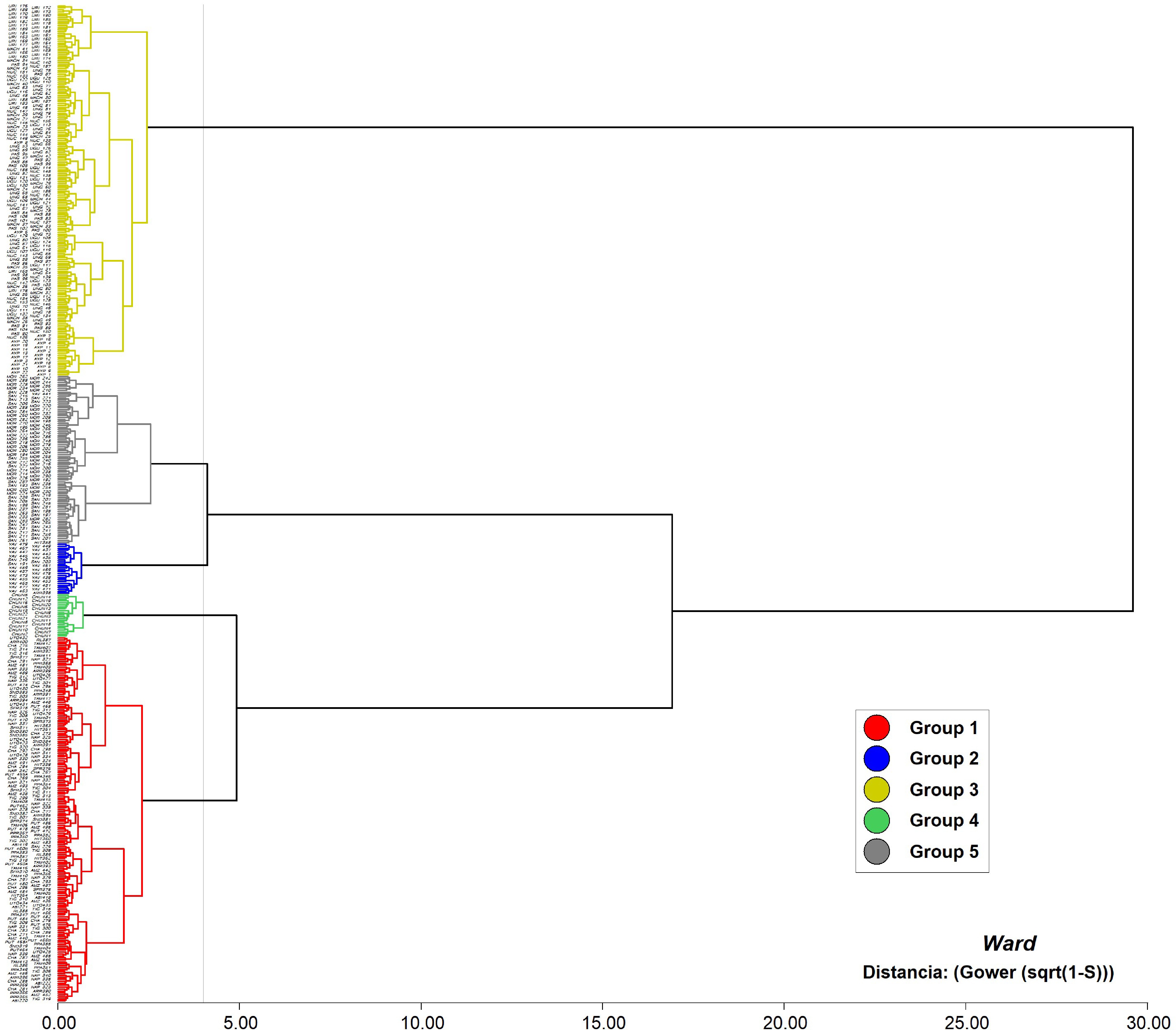

Cluster analysis identified five groups, almost entirely characterized by phenotypic traits, by using Ward's method and Gower distance (Gower distance = 3.8) for the leaf, flower, fruit, and seed descriptors that contributed most to variability (Fig. 3). The origin of the wild cacao accessions forming each group is shown in Table 6.

Figure 3.

Dendrogram resulting from the cluster analysis based on 27 agronomic traits of 511 wild cacao accessions from Peruvian river basins.

Table 6. Conformation of five phenotypic groups for 511 wild cacao accessions based on river basin of origin.

River basin Phenotypic groups Total accessions by

river basinGroup 1 Group 2 Group 3 Group 4 Group 5 Amazonas 17 (9.1%) 17 Aypena 22 (11.6%) 22 Chambira 20 (10.7%) 20 Madre de Dios 53 (28.3%) 1 (3.8%) 1 (1.2%) 55 Marañón 22 (11.6%) 22 Morona 50 (58.1%) 50 Napo 22 (11.8%) 22 Nucuray 25 (13.2%) 25 Pastaza 24 (12.6%) 24 Putumayo 18 (9.6%) 18 Santiago 1 (0.5%) 3 (11.5%) 34 (39.5%) 38 Tigre 22 (11.8%) 22 Ucayali 34 (18.2%) 34 Ungumayo 26 (13.7%) 26 Ungurahui 38 (20.0%) 38 Urituyacu 33 (17.4%) 33 Urubamba 22 (100%) 22 Yavari 22 (84.6%) 1 (1.2%) 23 Total group 187 26 190 22 86 511 • Group one consists of 187 wild cacao accessions from the Amazonas (9.1%), Chambira (10.7%), Madre de Dios (28.3%), Napo (11.85%), Putumayo (9.6%), Santiago (0.5%), Tigre (11.8%), and Ucayali (18.2%) river basins.

• Group two includes accessions from the Aypena (11.6%), Marañón (11.6%), Nucuray (13.2%), Pastaza (12.6%), Ungumayo (13.7%), Ungurahui (20.0%), and Urituyacu (17.4%) river basins.

• Group three is exclusively composed of wild cacao accessions from the Urubamba river basin.

• Group four includes accessions from the Madre de Dios (3.8%), Santiago (11.5%), and Yavarí (84.6%) river basin.

• Group five consists of accessions from the Madre de Dios (1.2%), Morona (58.1%), Santiago (39.5%), and Yavarí (1.2%) river basins.

This analysis highlights the high phenotypic diversity of these wild cacao trees.

The analysis of variance of characteristics across the main groups for all evaluated quantitative variables showed significant statistical differences (p ≤ 0.05). These differences were key determinants in the formation of the groups, except for leaf length (p = 0.4329), petiole length (p = 0.0830), and fruit weight (p = 0.9579).

The five cacao groups are quantitatively characterized by the 27 agronomic traits in Table 7. Group one comprises 187 wild cacao accessions. This group has the highest mean leaf length at 28.90 ± 0.13 cm, ranging from 23.7 to 32.8 cm, though not statistically different from the other groups. It also exhibits a high seed fresh weight of 108.10 ± 1.06 g, ranging from 62.50 to 166.13 g, statistically different from groups Two, Three, and Five. Similarly, seed dry weight is 39.43 ± 0.38 g, ranging from 24.4 to 63.2 g, significantly different from groups two, three, and five. The seed index is 1.20 ± 0.01 g, ranging from 0.87 to 1.64 g, also showing statistically significant differences from groups two, three, and five. Ovule length is 1.72 ± 0.01 mm, ranging from 1.30 to 2.04 mm, significantly different from the other four groups. Ovule width is 1.28 ± 0.01 mm, ranging from 0.96 to 1.60 mm, and is significantly different from groups two, three, and five. This group has a low pod index of 27.86 ± 0.29 fruits per kg.

Table 7. Mean values ± standard error and statistical significance for 27 leaf, fruit, seed, and flower descriptors for five cacao phenotypic groups from Peruvian Amazonia.

Traits* Group 1 Group 2 Group 3 Group 4 Group 5 CV % F p-value LL (cm) 28.94 ± 0.13 28.39 ± 0.36 28.65 ± 0.13 28.77 ± 0.39 28.85 ± 0.2 6.39 0.95 0.4329 LW (cm) 9.86 ± 0.07 a 10.27 ± 0.2 a 9.99 ± 0.07 a 9.49 ± 0.21 b 9.76 ± 0.11 a 10.09 2.66 0.0318 LBL (cm) 14.46 ± 0.09 b 14.58 ± 0.24 b 14.98 ± 0.09 a 14.18 ± 0.26 b 14.47 ± 0.13 b 8.27 5.91 0.0001 PL (cm) 1.78 ± 0.02 1.80 ± 0.05 1.86 ± 0.02 1.75 ± 0.06 1.79 ± 0.03 15.13 2.07 0.0830 FW (g) 567.72 ± 5.78 575.01 ± 15.5 567.70 ± 5.73 558.57 ± 16.85 571.03 ± 8.52 13.91 0.16 0.9579 SFW (g) 108.10 ± 1.06 a 104 ± 2.85 a 95.80 ± 1.05 b 95.51 ± 3.10 b 95.80 ± 1.57 b 14.42 21.03 < 0.0001 SDW (g) 39.43 ± 0.38 a 37.79 ± 1.01 a 34.99 ± 0.37 b 34.80 ± 1.10 b 35.01 ± 0.56 b 14.06 21.55 < 0.0001 FL (cm) 18.90 ± 0.08 a 19.06 ± 0.21 a 18.94 ± 0.08 a 19.18 ± 0.22 a 17.95 ± 0.11 b 5.61 16.43 < 0.0001 FD (cm) 12.01 ± 0.05 a 8.92 ± 0.15 b 12.07 ± 0.05 a 11.66 ± 0.16 a 9.06 ± 0.08 b 6.60 348.70 < 0.0001 FL/FD 1.61 ± 0.01 c 2.14 ± 0.03 a 1.60 ± 0.01 c 1.68 ± 0.04 c 2.05 ± 0.02 b 9.63 176.65 < 0.0001 FwD (mm) 7.50 ± 0.08 c 7.45 ± 0.22 c 8.05 ± 0.08 b 6.62 ± 0.24 d 11.28 ± 0.12 a 13.43 196.41 < 0.0001 HusT (mm) 13.63 ± 0.11 b 13.50 ± 0.29 b 17.37 ± 0.11 a 11.38 ± 0.31 c 17.03 ± 0.16 a 9.50 230.96 < 0.0001 SeN (n) 33.17 ± 0.26 b 32.50 ± 0.69 b 32.74 ± 0.25 b 36.67 ± 0.75 a 32.96 ± 0.38 b 10.60 6.45 < 0.0001 SI (g) 1.20 ± 0.01 a 1.20 ± 0.03 a 1.08 ± 0.01 b 0.95 ± 0.03 c 1.07 ± 0.01 b 11.48 37.4 < 0.0001 PI (n) 27.86 ± 0.29 c 28.74 ± 0.77 c 30.65 ± 0.28 b 34.61 ± 0.84 a 30.45 ± 0.42 b 13.23 22.78 < 0.0001 SeL (mm) 20.53 ± 0.08 b 20.36 ± 0.21 b 23.54 ± 0.08 a 18.35 ± 0.22 c 20.67 ± 0.11 b 4.85 290.59 < 0.0001 SeW (mm) 12.43 ± 0.04 b 12.39 ± 0.1 b 13.33 ± 0.04 a 10.99 ± 0.11 d 11.39 ± 0.06 c 4.26 251.82 < 0.0001 SeT (mm) 8.97 ± 0.04 b 8.95 ± 0.12 b 10.06 ± 0.04 a 6.74 ± 0.13 c 9.08 ± 0.06 b 6.31 204.54 < 0.0001 SepL (mm) 7.36 ± 0.05 b 6.85 ± 0.12 c 7.06 ± 0.05 c 7.84 ± 0.13 a 7.14 ± 0.07 c 8.65 13.60 < 0.0001 SepW (mm) 2.13 ± 0.02 a 2.00 ± 0.05 b 2.15 ± 0.02 a 2.25 ± 0.05 a 2.13 ± 0.03 a 11.48 3.41 0.0092 PeL (mm) 4.14 ± 0.03 c 4.20 ± 0.08 c 5.07 ± 0.03 a 3.38 ± 0.09 d 4.53 ± 0.05 b 9.24 165.64 < 0.0001 PeW (mm) 1.74 ± 0.02 c 1.74 ± 0.05 c 2.13 ± 0.02 a 1.66 ± 0.05 c 2.02 ± 0.03 b 12.29 78.65 < 0.0001 StL (mm) 5.21 ± 0.03 b 5.08 ± 0.07 b 5.26 ± 0.03 b 5.99 ± 0.08 a 4.79 ± 0.04 c 7.15 53.71 < 0.0001 OvL (mm) 1.72 ± 0.01 a 1.66 ± 0.04 b 1.67 ± 0.01 b 1.57 ± 0.04 b 1.66 ± 0.02 b 11.33 4.55 0.0013 OvW (mm) 1.28 ± 0.01 a 1.27 ± 0.03 a 1.04 ± 0.01 d 1.11 ± 0.03 c 1.17 ± 0.02 b 12.26 73.40 < 0.0001 StyL (mm) 2.25 ± 0.01 b 2.26 ± 0.04 b 2.48 ± 0.01 a 1.90 ± 0.04 c 2.21 ± 0.02 b 8.23 72.96 < 0.0001 Ov/o (n) 38.23 ± 0.20 b 37.61 ± 0.54 b 29.83 ± 0.20 d 35.32 ± 0.59 c 42.01 ± 0.30 a 7.80 364.99 < 0.0001 * Leaf traits: Leaf length (LL), Leaf width (LW), Length from base to the widest point of a leaf (LBL), Petiole length (PL). Fruit traits: Fruit weight (FW), Fruit length (FL), Fruit diameter (FD), Fruit length-to-diameter ratio (FL/FD), Furrow depth (FwD), Husk thickness (HusT), Pod index (PI). Seed traits: Seed fresh weight (SFW), Seed dry weight (SDW), Seed number per fruit (SeN), Seed index (SI), Seed length (SeL), Seed width (SeW), Seed thickness (SeT). Floral traits: Sepal length (SepL), Sepal width (SepW), Petal length (PeL), Petal width (PeW), Staminate length (StL), Ovary length (OvL), Ovary width (OvW), Style length (StyL), Ovules per ovary (Ov/o). Means with the same letter in a row are not statistically significant (p > 0.05). Group two, consisting of 26 wild cacao accessions, is characterized by high leaf width (10.27 ± 0.2 cm), ranging from 8.32 to 12.62 cm, which is significantly different from the leaf width of group three. The fruit weight (575.01 ± 15.50 g) ranges from 443.05 to 715.88 g but is not statistically significant from the other groups. The fruit length-to-diameter ratio (2.14 ± 0.03) ranges from 1.96 to 2.38 and is significant different from the ratio of the other groups. This group exhibits the lowest values for leaf length (28.39 ± 0.36 cm), fruit diameter (8.92 ± 0.15 cm), seed number per fruit (32.5 ± 0.69 seeds per fruit), sepal length (6.85 ± 0.12 mm), and sepal width (2.0 ± 0.05 mm).

Group three, which includes 190 wild cacao accessions, is characterized by a high value for length from base to the widest point of a leaf (14.98 ± 0.09 cm), ranging from 11.82 to 18.24 cm and is significant different from the other four groups. The petiole length (1.86 ± 0.02 cm) ranges from 1.26 to 2.40 cm and is not statistically significant compared to the other groups. The fruit diameter (12.07 ± 0.05 cm) ranges from 10.34 to 14.25 cm and is significantly different from groups four and five. The husk thickness (17.37 ± 0.11 cm) ranges from 10.79 to 16.99 cm and is statistically significant compared to groups one, three, and four. Additionally, this group has high values for:

• Seed length (23.54 ± 0.08 mm) ranging from 18.95–22.24 mm and statistically significant compared to groups two, three, and five.

• Seed width (13.33 ± 0.04 mm) ranging from 11.52–13.43 mm and statistically significant compared to all other groups.

• Seed thickness (10.06 ± 0.04 mm) ranging from 7.62–10.31 mm and statistically significant compared to all other groups.

• Petal length (5.07 ± 0.03 mm) ranging from 3.44–4.90 mm and statistically significant compared to all other groups.

• Petal width (2.13 ± 0.02 mm) ranging from 1.24–2.28 mm and statistically significant compared to all other groups.

• Style length (2.48 ± 0.01 mm) ranging from 1.94–2.53 mm and statistically significant compared to all other groups.

This group has low values for ovary width (1.04 ± 0.01 mm) and ovules per ovary (29.83 ± 0.20 ovules per ovary).

Group four represents only cacao from the Urubamba River basin, known as 'Chuncho'. This group has high values for:

• Fruit length (19.18 ± 0.22 cm) ranging from 15.9–20.9 cm and statistically significant only compared to group five.

• Seed number per fruit (36.7 ± 0.8 seeds per fruit) ranging 21.2–46.8 seeds per fruit and statistically significant compared to all other groups.

• Pod index (34.61 ± 0.84 fruits per kg) ranging from 16.4–41.4 fruits per kg and statistically significant compared to all other groups.

• Sepal length (7.84 ± 0.13 mm) ranging from 5.54–9.28 mm and statistically significant compared to all other groups.

• Sepal width (2.25 ± 0.05 mm) ranging from 1.44–2.74 mm and statistically significant only compared to group four.

• Staminate length (5.99 ± 0.08 mm) ranging from 4.16–5.96 mm and statistically significant compared to all other groups.

In this group, the lowest values were found for multiple traits, including leaf width (9.49 ± 0.21 cm), length from base to the widest point of a leaf (14.18 ± 0.26 cm), petiole length (1.75 ± 0.06 cm), fruit weight (558.57 ± 16.85 g), seed fresh weight (95.51 ± 3.10 g), seed dry weight (34.80 ± 1.10 g), furrow depth (6.62 ± 0.24 mm), husk thickness (11.38 ± 0.31 mm), seed index (0.95 ± 0.03 g), seed length (18.35 ± 0.22 mm), seed width (10.99 ± 0.11 mm), seed thickness (6.74 ± 0.13 mm), petal length (3.38 ± 0.09 mm), petal width (1.66 ± 0.05 mm), ovary length (1.57 ± 0.04 mm), and style length (1.9 ± 0.04 mm).

Group five consists of 86 accessions, mainly from the Santiago and Morona river basins. This group has high values for:

• Furrow depth (11.28 ± 0.12 cm) ranging 7.32–16.93 cm and statistically significant compared to all other groups.

• Ovules per ovary (42.0 ± 0.3 ovules per ovary) ranging 37.6–47.4 ovules per ovary and statistically significant compared to all other groups.

The lowest values found in this group were for fruit length (17.95 ± 0.11 cm) and staminate length (4.79 ± 0.04 mm).

-

This preliminary study represents one of the most extensive phenotypic characterizations of wild cacao populations in the upper Amazon region, with quantitative morphological descriptors to characterize 511 wild cacao accessions from 18 Peruvian river basins. It reveals significant morphological diversity and distinct patterns of variation, providing valuable insights into the genetic resources of T. cacao in its center of diversity.

Dias et al.[34] studied the diversity and distribution pattern within and among wild cacao populations from the Brazilian Amazon. Fourteen descriptors were used to assess 320 cacao trees from four river basins. The study found that the river basin is a key factor influencing variation in cacao populations. This result aligns with the present findings, as most variables showed significant differences among river basins. However, the variability within accessions from the same river basin was inconsistent, with some variables exhibiting homogeneity and others heterogeneity[34]. Dias et al.[34] also found high variability within the river basins. These results can be explained by the fact that the sampling process was randomized or showed the influence of the tree age or time of sampling.

The substantial variation observed in 24 of the 27 quantitative traits related to leaf, fruit, seed, and flower descriptors highlights the remarkable phenotypic diversity within these wild cacao populations[32]. The high coefficients of variability (CV > 10%) for most traits align with previous findings by Motamayor et al.[35] who reported significant morphological variation in Amazonian cacao populations. Notably, the seed index showed the highest variability (CV = 54.3%), while seed width exhibited the lowest (CV = 8.5%), suggesting different selective pressures on these traits during evolution.

It is important to note that the evaluation of quantitative traits in this study was conducted under high-density planting conditions. This approach facilitates the assessment of a large number of accessions but may influence trait expression differently compared to evaluations conducted under recommended commercial spacing for cacao cultivation. Future studies should incorporate field trials with standard agronomic practices to validate the adaptability of selected accessions under real cultivation scenarios.

Leaf morphology revealed subtle yet significant variations among the clustered groups. While leaf length remained relatively uniform (28.39–28.94 cm), significant differences were observed in leaf width, with group four exhibiting notably lower leaf width (9.49 cm, p ≤ 0.05). This variation in leaf morphology may represent adaptations to specific environmental conditions, as this group consists exclusively of cacao 'Chuncho' from the Urubamba River basin, a high-altitude region where cacao grows. Accessions in this group were collected within a narrow valley at 665 and 1,478 m above sea level. This environment differs markedly from the other lower-elevation valleys from which other accessions were collected. Similar findings were reported by Daymond et al.[36], who demonstrated that cacao leaf characteristics are highly responsive to environmental factors such as light intensity and water availability[36]. Group four also had lower length from base to the widest point of a leaf, petiole length, fruit width, seed fresh weight, seed dry weight, furrow depth, husk thickness, seed index, seed length, seed width, seed thickness, petal length, petal width, ovary length and style length but higher fruit length, seed number per fruit, pod index, sepal length, sepal width, and staminate length, as was reported by García-Carrion[28]. As mentioned earlier, cacao 'Chuncho' may have developed unique traits in response to specific environmental pressures in the region, similar to morphological adaptations observed in other cacao populations[13]. These observations are consistent with previous studies indicating that geographic location and specific ecological conditions play a crucial role in shaping genetic diversity within cacao populations[37]. The results also support the hypothesis of distinct genetic lineages evolving in isolated river valleys[38,39], as geographical barriers have played a crucial role in cacao diversification.

In the future, integrating international cacao clones into studies should provide a comparative perspective, positioning the observed variation within the global context of cacao genetic resources. This approach would offer a clearer understanding of how Peruvian wild cacao compares with widely cultivated varieties available internationally. Vásquez-García et al.[32] characterized 130 cacao genotypes from the germplasm bank at the Instituto Nacional de Innovación Agraria in Peru, by using 20 morphological descriptors and 31 agronomic descriptors of the leaf, flower, fruit, and seed, and identified five clustered groups. Principal components analysis in the present study revealed that eight traits (fruit diameter, fruit length-to-diameter ratio, furrow depth, husk thickness, seed length, seed width, petal length, and ovules per ovary) significantly contributed to group differentiation, explaining 72.3% of the total phenotypic variation. This multi-trait differentiation suggests complex patterns of adaptation and genetic drift across river basins, consistent with the findings of Thomas et al.[40], who reported spatial genetic structuring in neotropical cacao populations.

The clustering of accessions into five distinct phenotypic groups based on similar traits and geographical origin suggests a strong ecological adaptation across river basins. This pattern aligns with Thomas et al.[40], who reported robust eco-geographical patterns in cacao diversity that reflect natural evolutionary processes and human selection. Group One consists of cacao accessions from diverse river basins that are geographically distant from each other (Amazonas, Chambira, Madre de Dios, Napo, Putumayo, Santiago, Tigre, and Santiago), highlighting the role of isolation and distinct environmental conditions in promoting cacao genetic diversity[13,38]. On the other hand, group three, which includes cacao from the Aypena, Marañón, Nucuray, Pastaza, Ungumayo, Ungurahui, and Urituyacu River basins, exhibits greater homogeneity, likely due to the geographic proximity of these river basins around the Marañón River[40].

The analysis of reproductive traits revealed notable variations in productivity indicators. Group four exhibited the highest pod index (34.61), which was significantly different from groups one and two (27.86 and 28.74, respectively. The results in this study reports values higher than those typically observed in elite cacao[20−25], suggesting potential for improvement through selective breeding[41]. However, group four also exhibited other traits, such as the highest number of seeds per fruit (36.67, p ≤ 0.0001), that align with the findings of Motamayor et al.[13] regarding the complex nature of yield components in cacao.

Seed indices, which are crucial for the commercial quality of cocoa beans, varied significantly (p ≤ 0.0001), with groups one and two having the highest values (1.20 g), aligning with international market preferences for beans larger than 1.2 g[42]. The lower seed index in group four (0.95 g) suggests that individual seed weight may have been compromised despite its higher seed count, illustrating the typical negative correlation between seed number and size observed in many crops[43].

Fruit quantitative traits showed distinct patterns among groups, with significant variations in fruit dimensions and husk thickness (p ≤ 0.0001). Group four's combination of traits - thinner husks (11.38 mm) but higher seed numbers - presents both opportunities and challenges for breeding programs. While thinner husks might increase susceptibility to pests[34], this characteristic could also facilitate harvesting operations[34].

There was significant variation in floral traits, particularly in ovule number per ovary (p ≤ 0.0001). Group five exhibited the highest values (42.01), suggesting diverse reproductive strategies among groups. These differences in floral morphology could influence pollination success and compatibility systems, which are critical factors for cacao yield improvement[44,45].

The spatial pattern of diversity which was observed underscores the importance of river basins as drivers of genetic differentiation in the Amazon. This diversity is crucial for maintaining genetic resources that could contribute to future breeding objectives to improve cacao resilience and sustainability[39,46]. Determining accessions with superior traits presents valuable opportunities for cacao improvement. For instance, accessions with seed indices greater than 1.5 g (AMZ 446 = 1.64 g, PPR 365 = 1.56 g, and TIG 315 = 1.53 g) represent exceptional breeding material. These values exceed the average seed index reported by Ballesteros et al.[47] for cultivated varieties (1.2–1.4 g). Accessions with high productivity potential, characterized by favorable pod index values less than 21 in multiple river basins, suggest the presence of highly productive genotypes. Bekele & Phillips-Mora[48] reported that such traits are crucial for developing improved varieties with enhanced yield efficiency. The significant variation in fruit diameter, fruit length-to-diameter ratio, and husk thickness across groups suggests different strategies for seed protection and dispersal, potentially contributing to disease resistance[13].

The morphological diversity observed in wild cacao across river basins suggests the proposal of in situ conservation strategies. The following actions are recommended: 1) Prioritize conservation efforts in regions harboring unique phenotypic profiles, particularly the Urubamba, Morona, and Santiago River basins; 2) Implement targeted collection strategies to capture the full range of trait variation; and 3) Develop core collections that represent the phenotypic diversity identified in the present study.

-

This study provides a comprehensive quantitative phenotypic baseline of wild cacao diversity in the Peruvian Amazon and offers valuable insights for future cacao breeding programs and conservation strategies. The significant diversity observed reinforces this region's status as a key center of cacao genetic resources, highlighting the need for continued research and conservation efforts to safeguard and utilize this invaluable germplasm. Moreover, genotyping-by-sequencing is being applied to these wild cacao accessions to elucidate the genetic basis of the observed phenotypic variations. The combined analysis of genomic and phenotypic data will enhance the utilization of wild cacao germplasm for crop improvement.

We thank the USDA-ARS for supporting the field trial activities under Project Agreement Number (Grant No. FAIN 58-8042-2-042-F). We are also grateful to the 'Programa Nacional de Investigación Científica y Estudios Avanzados' (National Program for Scientific Research and Advanced Studies) (PROCIENCIA) for financial support (Grant No. 188-2020), with special appreciation to Ana María Ramos Hurtado for her timely advice in developing this work. We extend our gratitude to all technicians who participated in the collection and establishment of the germplasm bank at the Instituto de Cultivos Tropicales (ICT) in Tarapoto, as well as to ICT for providing the field and laboratory facilities necessary for this study.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Arévalo-Gardini E, Baligar V, Zhang D; data collection: Arévalo-Gardini E, Flores-Isuiza G, Zuñiga-Cernades LB, Ruiz-Camus CE, Tuesta-Hidalgo OA, Arévalo-Gardini J; analysis and interpretation of results: Arévalo-Gardini E, Arévalo-Hernández CO, Zhang D; draft manuscript preparation: Arévalo-Gardini E, Arévalo-Hernández CO, Mehinhard L, Zhang D. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Due to administrative requirements, the original data of the experiments during the project's research period are not available to the public. However, the data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Arévalo-Gardini E, Arévalo-Hernández CO, Flores-Isuiza G, Zuñiga-Cernades LB, Arévalo-Gardini J, et al. 2025. Phenotypic diversity of wild cacao in Peru's largest germplasm bank: novel insights for breeding and conservation. Beverage Plant Research 5: e037 doi: 10.48130/bpr-0025-0024

Phenotypic diversity of wild cacao in Peru's largest germplasm bank: novel insights for breeding and conservation

- Received: 09 December 2024

- Revised: 13 May 2025

- Accepted: 29 May 2025

- Published online: 28 November 2025

Abstract: The Amazon rainforest is a significant center of origin for Theobroma cacao L. (cacao), and understanding the phenotypic diversity of its wild populations is crucial for genetic improvement and conservation strategies. In this study, the phenotypic diversity of 511 wild cacao accessions, collected between 2008 and 2015 from 18 river basins in the Peruvian Amazon and subsequently conserved at the germplasm bank of the Instituto de Cultivos Tropicales in Tarapoto, Peru, was evaluated. Phenotypic diversity was assessed using 27 quantitative traits related to leaves, fruits, seeds, and flowers. The results revealed significant differences in trait expression among river basins, highlighting the influence of environmental conditions on phenotypic variation. Notably, accessions from the Amazonas, Madre de Dios, and Tigre basins exhibited the highest seed index, while the best pod index was recorded in Madre de Dios, demonstrating considerable variability in yield potential. Similar trends were observed in pod weight, seed number per pod, and fruit dimensions, underscoring the role of geographical origin in shaping phenotypic traits. Phenotypic diversity analysis using principal component analysis and hierarchical clustering identified five distinct groups among the wild cacao accessions. These findings offer valuable insights for selecting superior genotypes adapted to specific environmental conditions and lay the groundwork for future breeding programs to enhance cacao productivity and resilience.