-

India has been cultivating mushrooms since the 1970s. However, due to the development of modern technologies for environmental control and knowledge of the various cultivation systems, mushroom production has significantly increased. In 2010, the mushroom production of India comprised 89% button mushrooms, 6% oyster mushrooms, 1% milky mushrooms, and 4% others[1]. The production spans from an extremely technical enterprises to quite archaic farming practices. Mushroom cultivation is an ancient practice that has evolved into a modern agricultural pursuit fueled by scientific advancement[2]. We can trace evidence of primitive cultivation as early as 600 AD in China in the form of, for example, Auricularia auricula-judae grown on wood logs, as mentioned in historical manuscripts like the Compendium of Materia Medica[3]. This method depended on the existing decomposition of wood by fungi, and growers simply had to identify moist, shaded locations and then bide their time until the fruiting bodies sprouted. Yields were variable, depending on the weather and substrate quality, but this was the beginning of deliberate mushroom propagation. Likewise, Lentinula edodes (shiitake) cultivation in Japan started around 1000 AD, using logs inoculated with spores, which was labor-intensive and perfected over generations but still subject to seasonal restrictions and low output[4]. In Europe, the 17th century saw the cultivation of fungi growing in an alternate direction, as Agaricus bisporus was identified (the button mushroom, first cultivated in France)[5]. By the 18th century, cultivation extended to Britain and the Netherlands, where growers experimented with deeper beds and crude shelters, yet scalability remained elusive and without scientific control. Mushroom farming was established later in India, where commercial cultivation began in the 1970s, driven by imports of technology and local variations, such as the cultivation of oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus spp.) on rice straw[6]. As scientific knowledge increased in the 20th century, the shift to complex systems started. By enabling controlled inoculation, spawn (fungal mycelium on a carrier) was developed in the early 1900s, lowering the danger of contamination and increasing the dependability of production[7]. By the middle of the century, controlled conditions, such as temperature-controlled growth chambers and substrate pasteurization, had developed, especially for A. bisporus, increasing production from a few kilos to tons every cycle. By the 2010, 94,676 tons of white button mushrooms were produced annually, accounting for 70% of India's total production[8]. As a result of these advancements, biology and technology came together to form today's intricate systems.

Unlike conventional biology, which examines individual components (e.g., genes or proteins), systems biology analyzes networks of interactions—metabolic pathways, gene regulation, and environmental responses—within an organism[9]. A treasure trove of bioactive compounds with significant medicinal qualities lies within mushrooms beyond their nutritional value. The antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidant properties of terpenoids and polysaccharides, including beta-glucans, that are present in mushrooms have been thoroughly investigated[10]. These compounds have significance for lowering oxidative stress, regulating the immune system, and preventing the formation of cancer cells. In preclinical investigations, lentinan from Lentinula edodes and grifolin from Grifola frondosa have shown strong anticancer benefits. Systems biology optimizes the conditions for production and quality in mushroom farming by modeling the dynamics of fungal growth, substrate consumption, and the synthesis of bioactive compounds[11]. It allows for accurate temperature, humidity, and nutrient availability modifications, for example, which improve the production of species like Pleurotus ostreatus, Agaricus bisporus, and Lentinula edodes.

By combining omics technologies—like genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—systems biology helps researchers understand the molecular networks involved in mushrooms' growth and development. For example, transcriptomic analysis can show the gene expression patterns linked to stress responses, which aids breeders in creating stronger mushroom strains[12]. Meanwhile, metabolomic profiling can pinpoint metabolic bottlenecks in producing bioactive compounds, allowing for focused efforts to boost their production. Modern technologies, such as the Internet of Things (IoT), have revolutionized mushroom farming via live monitoring and control of growth parameters. With IoT-based solutions, mushroom growth conditions can be monitored for light, CO2, temperature, and humidity[13]. Using synthetic biology technologies such as CRISPR/Cas9, new potential for enhancing mushroom strains have opened up. Because CRISPR/Cas9 eliminates genes that cause browning, it can enhance the shelf life of mushrooms and decrease post-harvest losses. Genome alterations can increase desirable features such as yield, resistance to pests, and bioactive substance content[14]. Together, these methods support the creation of precision farming strategies that increase productivity and quality while reducing the environmental impact. This review emphasizes the importance of systems biology in shaping the future of mushroom cultivation in order to contribute to food security, health, and sustainability.

-

The health advantages of mushrooms are numerous, and they are used in traditional medicine. A recent field of study called ethno-mycology examines how local communities interact with fungi. It covers customary, recreational, and cultural applications of mushrooms. This resource is underutilized and naturally renewable, and enhances rural livelihoods[15]. For nutritional and financial gain, people gather wild mushrooms, which are classified as non-timber forest products (NTFPs). The methods used by various societies to gather and use these wild culinary mushrooms differ. They are gathered and sold for their culinary and commercial value[16]. Rural residents also rely heavily on morels as an alternative source of both sustenance and cash[17]. Conventional therapies employ them to treat common illnesses. Frequently, edible mushrooms are utilized to make nutraceuticals and medications that have antitumor, antioxidant, and antibacterial qualities[18]. Minimal sodium and abundant potassium in mushrooms help improve salt balance and facilitate blood circulation in humans, and they are suitable for patients with high blood pressure. Diabetic and overweight/obese patients select mushrooms as their perfect meal due to their low calorie value, lack of starch, and decreased sugar content. Tumor-inhibiting compounds such as kresin are widely utilized as a leading anticancerous compound in the pharmaceutical industry[19]. Ergothioneine is a particular antioxidant found in Flammulina velutipes and Agaricus bisporus that is fundamental for eyes, kidneys, bone marrow, liver and skin, thereby reducing the detrimental effects of aging. An assorted set of polysaccharides (beta-glucans) and minerals plays a part in controlling and upgrading the human resistance system. White mushrooms contain selenium, which makes a difference in overweight/obesity and is known to protect against prostate cancer[20].

Major economic uses of mushroom cultivation

-

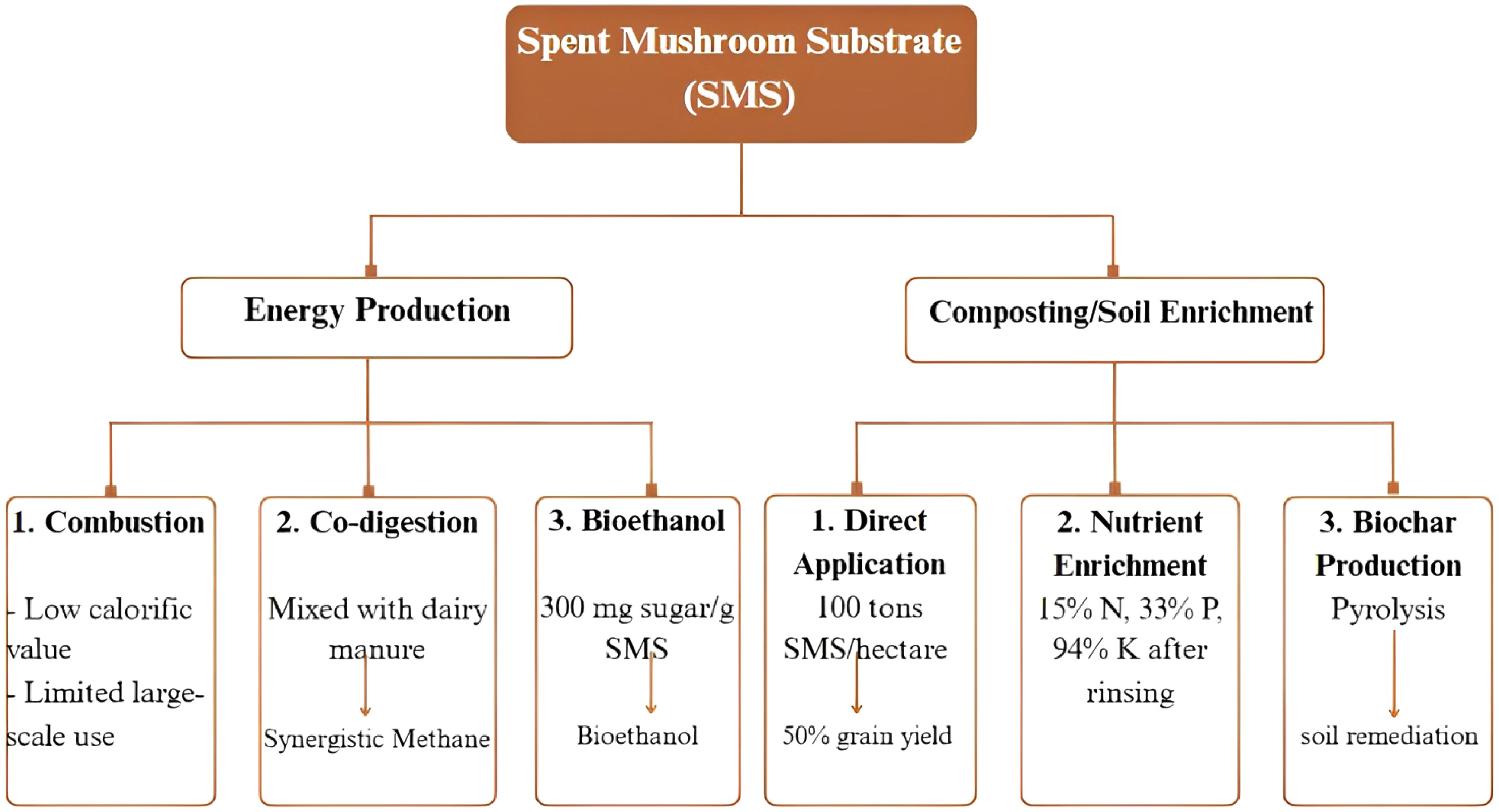

Economic growth is greatly aided by the production of mushrooms, especially when spent mushroom substrate (SMS) is used. Mushroom cultivation has extended its sale globally with an annual growth rate of 2000. The market value was estimated to be worth over USD

${\$} $ Composting SMS is another important economic purpose, especially when it comes to tackling the problems with contemporary farming methods[29]. For instance, the application of 100 tons of SMS per hectare has been shown to increase grain yield by 50%, which is similar to the effects of inorganic fertilizers[30,31]. Rinsing SMS with filtered water significantly boosts its nutrients, increasing nitrogen levels by 15%, phosphorus by 33%, and potassium by 94% after 60 days, making it safe and effective for agricultural use[32]. In addition, pyrolysis enables the conversion of SMS into biochar, as shown in Fig. 1, which is another alternative for organic fertilizers with limited environmental concerns (e.g., groundwater contamination)[33] [34]. Mushrooms operate as biological medicinal potentials while supporting the environment. Medicinal mushrooms such as Ganoderma lucidum (reishi) and Lentinula edodes (shiitake) produce bioactive compounds like polysaccharides (e.g., lentinan) and terpenoids, which exhibit anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory properties[35]. Lentinan, for example, is an injectable anticancer medication that has been licensed in Japan and, when used in conjunction with chemotherapy, increases the survival rates of patients with stomach cancer[36]. In a similar vein, polysaccharide-K (PSK)-rich extracts from turkey tail mushrooms (Trametes versicolor) are utilized in clinical settings to boost immunity in patients with breast cancer. Beyond cancer, mushrooms have shown potential in the treatment of neurological illnesses like Alzheimer's disease, autoimmune disorders, and persistent viral infections like hepatitis and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)[37]. There are, however, still controversies. Research published in 2020 found that 40% of marketed Cordyceps supplements were very low in bioactive chemicals, raising concerns about their safety and effectiveness[38]. The mushroom remains a frontier for drug development, with over 100 medicinal qualities reported, including hepato-protective properties and antiviral activity (e.g., against Herpes simplex virus [HSV])[39].

Traditional systems suffer from severe drawbacks, such as the slow growth rates of macro-fungi on forestry and agricultural residues, inefficient substrate conversion, and a lack of capability to rapidly breed for desired traits. Consequently, there is wasted biomass and economic potential, with SMS usually only having low-value uses such as compost or animal feed. However, modern biotechnology is changing this paradigm. With the help of synthetic biology technologies like precision metabolic pathway engineering, chassis strain selection and adaptation, custom gene circuit design, and combinatorial genetic assembly[40], researchers can now rewire the molecular machinery of mushrooms, as depicted in Fig. 2. This can provide the means to generate strains with faster growth rates, an enhanced ability to break down complex lignocellulosic waste streams, and the ability to produce targeted high-value metabolites (such as nutraceuticals, enzymes, and flavors).

Figure 2.

The evolution of design science has altered mushroom growth from a focus on regular improvements to extensive applications based on advanced biotechnology. (a) Inefficiencies in traditional agriculture include restricted SMS reuse, sluggish growth, and poor substrate usage. Value creation possibilities are lost, and waste is produced by the linear approach. (b) To rewire mushrooms for better qualities, the synthetic biology toolkit employs metabolic engineering, gene circuits, and chassis design. Precision breeding allows for faster development of strains with optimized growth, substrate digestion, and metabolite profiles. Engineered strains convert SMS into advanced materials and energy[14].

Mushroom species transform bio-recalcitrant lignocellulose waste materials from agricultural (rice straw and corn husk) and industrial sources (sawdust and coffee pulp) into nutritious protein products[41]. For instance, Pleurotus spp. cultivated on Colombian coffee waste, produces 15–20 kg of mushrooms for each substrate, resulting in waste reduction and economic circularity[42], and Indian researchers use Volvariella volvacea mushrooms to transform rice straw into products[43,44]. The study of systems biology serves to enhance these procedures by mapping metabolic pathways for optimizing enzyme secretion together with lignocellulose breakdown. The field can advance through CRISPR technology, which produces modified Aspergillus strains that demonstrate 40% higher ligninase activity for better waste conversion performance[45]. Laboratory techniques that combine CRISPR technology have improved the medicinal value of Ganoderma lucidum by creating strains that produce 2.5 more immunomodulatory triterpenes for anticancer treatments[46]. Through the combined application of bioconversion and bioactive compound synthesis, systems biology, and CRISPR, researchers have created sustainable health-oriented solutions that confront worldwide waste challenges and medical issues.

Systematic analysis of bioactive components in edible mushrooms

-

The health benefits of bioactive components in edible mushrooms fall into specific categories according to their biological activities and mechanisms of action. The framework of systems biology enables researchers to understand the chemical processes and genetic networks that govern mushroom production and effectiveness.

Antibacterial activity

-

Edible mushrooms contain three important structural compounds, terpenoids, lectins, and polypeptides, which cause bacterial cell membrane deficiencies and protein synthesis blockage. The production of terpenoids with antimicrobial activity is a unique ability in Ganoderma and Phellinus spp.[47], while Polyporus umbellatus damages Staphylococcus aureus through its cytotoxic steroid compounds[48]. Research techniques using transcriptomics can pinpoint specific gene groups (such as cytochrome P450) responsible for terpenoid biosynthesis in Ganoderma[49].

Anticancer potential

-

Polysaccharides (lentinan) and triterpenoids, along with steroids, show potential as anti-cancer agents, as suggested in previous studies. These compounds cause apoptosis by generating reactive oxygen species (ROS) while blocking mitotic protein enzymes. Examples include treatment of gastric cancer with Trametes versicolor producing polysaccharide-K (PSK)[50], while Polyporus umbellatus steroids inhibit the progression of breast cancer[51]. Systems biology techniques utilizing CRISPR-edited Ganoderma lucidum strains have increased triterpenoid synthase expression, leading to higher production of anticancer compounds[52].

Antioxidant properties

-

Mushrooms contain four main antioxidants, including phenolics, flavonoids, carotenoids, and vitamin E. These compounds both eliminate free radicals and bind metal ions in order to stop oxidative stress damage. Two examples of antioxidant-enriched mushrooms are Armillaria mellea with vanillic acid and cinnamic acid, and Macrolepiota procera with protocatechuic acid at high levels[53]. The metabolomics approach, together with omics methods, shows how A. mellea, as well as other mushrooms, produce phenolic acids through biosynthetic pathways while environmental conditions like soil pH influence antioxidant production levels[54].

Antiviral effects

-

Two main compounds include β-glucans and proteases. Experimental findings showed that Pleurotus spp. (oyster mushrooms) displayed viral inhibition properties predicted by network modeling and promoted better antiviral immunity[55]. Pleurotus sp., along with other species, demonstrates antiviral characteristics against HSV[39].

Various bioactive compounds from edible mushrooms work precisely on molecular pathways to deliver health benefits to the human body. A summary in Table 1 below shows the most important compounds found in edible mushrooms, along with their origins and molecular functions, as well as their antioxidant, antimicrobial, antiviral, and cancer-preventive properties.

Table 1. Key bioactive compounds and associated health benefits

S. no. Bioactive compound Mushroom species Health benefit Mechanism Source 1. β-Glucans Pleurotus spp. Anticancer, antiviral Immune receptor activation Medihi et al.[55] 2. Lentinan Lentinula edodes Immune modulation, Antitumor Apoptosis induction Yadav & Negi[36] 3. Vanillic acid Armillaria mellea Anti-inflammatory, Antioxidant Free radical scavenging Erbiai et al.[53] 4. Protocatechuic acid Macrolepiota procera Antioxidant, cardio-protective Metal ion chelation Erbiai et al.[53] 5. Terpenoids Ganoderma lucidum Antibacterial, anticancer Membrane disruption Câmara et al.[47] -

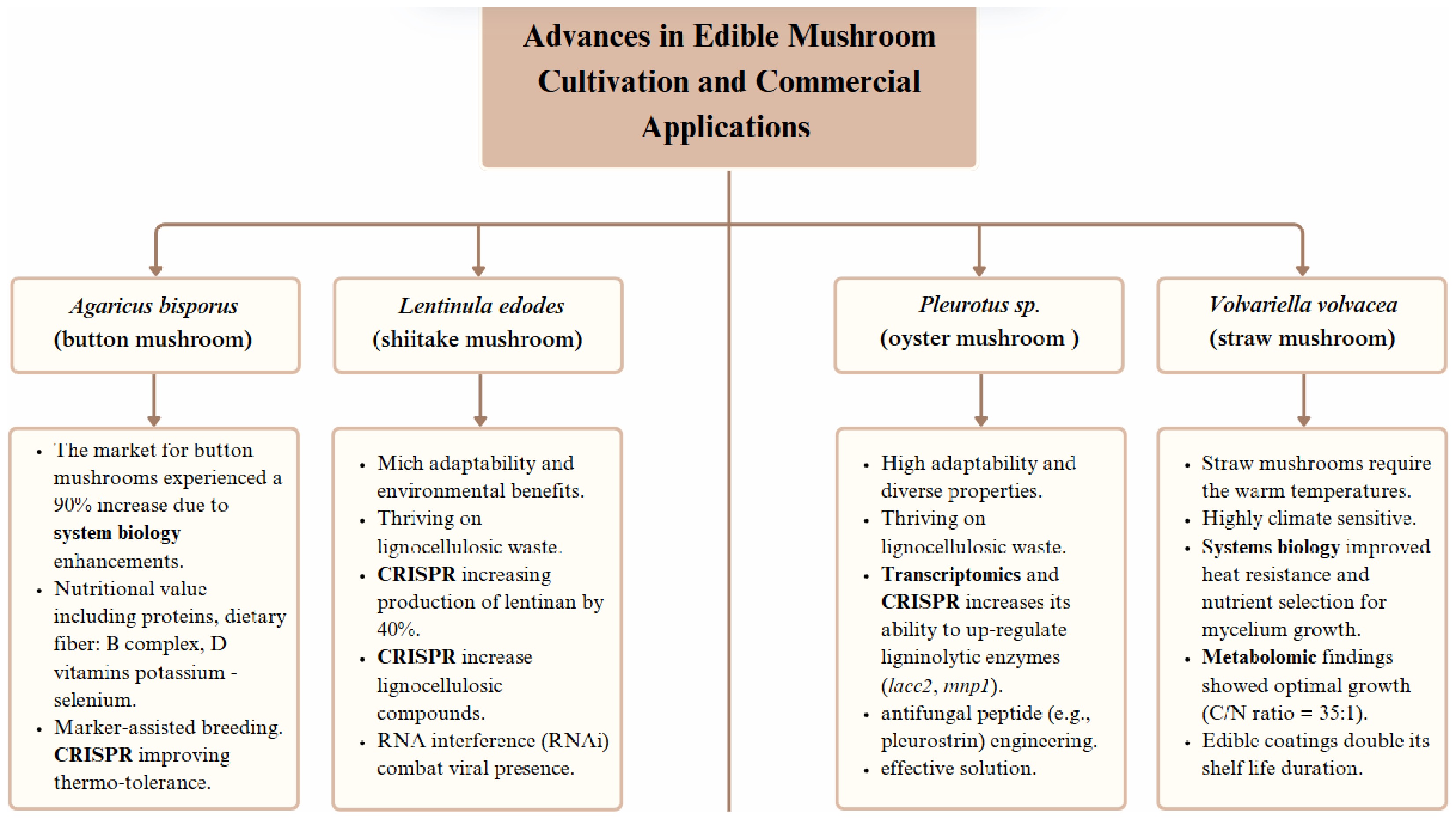

The total number of current mushroom species exceeds 2000, despite the fact that only 25 types are safe for human consumption and only a few species are grown commercially[56]. Among all cultivated species, Agaricus bisporus stands as the top global market leader, while Pleurotus spp. and Lentinula edodes follow as the second most produced species. They harbor antimicrobial compounds, found mainly as secondary metabolites, that include terpenes, steroids, anthraquinones, benzoic acid derivatives, and quinolones[57]. Systems biology interventions have the potential to enhance Agaricus bisporus button mushrooms, since they represent 40% of the market. The A. bisporus genome, containing 30.2 Mb with 11,000 genes, allows scientists to identify lignocellulose degradation genes such as AA9 lysitic polysaccharide monooxygenases to assist in selecting disease-resistant mushroom strains through marker-assisted breeding[58]. The commercial success of systems biology-driven hybrid strains, specifically A. bisporus var. burnettii, demonstrates better yield performance and longer shelf stability[59] that open up fresh market opportunities worldwide.

Lentinula edodes is the third most cultivated mushroom in the world because of its medicinal worth. The demand for Lentinula edodes exceeds 8 million tons per year because of its high economic value. Systems biology research performed on shiitake mushrooms revealed essential gene changes and metabolic system modifications that have boosted the development of mushrooms, along with their bioactive compounds. During the fruiting phase, transcriptomics research showed that LELent1 (lentinan synthase) and LEGlu1 (β-1,3-glucanase) genes are expressed more frequently[60]. The implementation of CRISPR technology on specific genes increased lentinan production by 40%[61]. Every year, shiitake extract sales generate

${\$} $

Figure 3.

Overview of major edible mushroom species and the related systems biology advancements in yield, disease resistance, and commercial applications. Created with Biorender.

Mushrooms are gaining popularity in international trade and new consumer segments due to their increased shelf life. Systems biology is remodeling their functional value, unlocking premium price opportunities for value-added traits, opening up new product categories, and expanding global sustainability for the grown edible mushroom market. Table 2 below presents vital information about transcriptomic discoveries and commercial applications, as well as current market valuations.

Table 2. Insights into market value and commercial uses from transcriptomic research

S. no. Mushroom species Key transcriptomic findings Application in commercial settings Market value Source 1. Button mushroom

(Agaricus bisporus)Upregulation of temperature-sensitive heat shock protein genes (HSP70/90). Developing disease-resistant hybrids for the global food market. Dominates the global market, value (over

USD ${\$} $15 billion)Feng et al.[70] 2. Shiitake mushroom (Lentinula edodes) Increase in LELent1 and LEGlu1 gene expression boosts lentinan synthesis. Production of nutraceuticals for immune support Premium segment valued at USD ${\$} $8–10 billion Konno et al., [60] 3. Oyster mushroom

(Pleurotus spp.)lacc2/mnp1 enhances lignin degradation Waste-to-food project ~USD ${\$} $3 billion Salami et al.[64] 4. Straw mushroom (Volvariella volvacea) Evaluation of VvHSP60 found to increase mushroom production by 15%. Enhancing the sustainability of tropical agriculture ~USD ${\$} $1 billion Bao et al.[65] -

The oldest form of mushroom cultivation is outdoor wood cultivation, which has been used for shiitake cultivation in China for at least 1000 years. This method is now commonly replaced by more attractive indoor developments using "artificial logs", which are plastic bags filled with a complementary sawdust-based substrate. Once the bag is filled, it is lowered to allow fruiting. The sawdust is held like a stick by the mycelium and does not fall out. Long plastic packages hanging from the ceiling, resembling counterfeit logs, are typical of pyramid societies[67]. Once the mycelium colonizes these bags, gaps are created in the plastic to allow the mushrooms to set fruit. The fast growth of modern agriculture is now more promising due to the effect of systems biology. Multi-omics data—genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—have been integrated in systems biology to model the complex networks of fungal growth, substrate utilization, and bioactive compound synthesis. These networks are mapped using systems biology to determine the locations where material or product flows slow down. A study of Lentinula edodes found that the synthesis of lentinan (an immunomodulatory β-glucan) happens most during the fruiting phase, due to the significant increase in LELent1 and LEGlu1 during the process[68]. Optimizing light cycles and temperature helped industrial farms add 25% more lentinan to their yields compared with previously. A similar approach for Ganoderma lucidum found that oxygen was critical for producing triterpenes[69]. Consequently, bioreactors were created to ensure good oxygen levels during fermentation. Machine learning (ML) tools are used to analyze omics data and predict the best settings for the growth of the cells. A report from 2024 used proteomic analyses and information on humidity and CO2 levels for Agaricus bisporus to design an artificial intelligence (AI) system that recommended that mushroom growing substrates should have a carbon/nitrogen (C/N)_ratio of 25–30 and have a moisture level of 65%–70%[70]. Those investing in this system have recorded a 30% lower use of water and nutrients. Scaling these models is achieved through IoT-enabled systems, where collected sensor data allow the algorithms to automatically adjust the climate settings. ML tools help to discover new bioactive compounds from mushroom metabolomes. Studies carried out in 2024 used deep neural networks to discover compounds with high potential to inhibit acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity in medicinal mushrooms, which helps fight Alzheimer's disease[71]. This strategy is a process of finding new drugs and reduces laboratory expenses. The use of multi-omics has uncovered the biological effects of environmental stress. With the help of systems biology, biologists made targeted changes to genes using CRISPR, which allowed mycelia to thrive at 35°C. In Pleurotus ostreatus, redox proteomics showed that the ability to withstand oxidative stress relies on glutathione production, helping assemble antioxidant-friendly cultures[72]. Systems biology is the basis of information for creating synthetic gene circuits. One such example involves Ganoderma lucidum, where a synthetic feedback loop was engineered to overexpress antioxidants (e.g., superoxide dismutase) in the presence of oxidative stress, increasing its medicinal potency. This "smart mushroom" technology adjusts to changes in the environment, illustrating the synergy between systems and synthetic biology. Using microorganisms in agriculture, synthetic biology has the ability to modify the genetic makeup and metabolic pathways of crops. Thus, crop breeding, yield improvement, and maintaining the security of the farming environment are the areas where it has a promising future[73]. Through the use of molecular biology tools, the field of synthetic biology has made tremendous progress in creating biological functions. Synthetic biology's application in agriculture demonstrates the possibility for modifying genetic circuits, plant structures, and metabolic processes to improve crops[74]. By using microorganisms with synthetic biology for bio-control, bio-stimulation, and bio-fertilization, sustainable agriculture can profit in the interim. Exceptional hereditarily encoded assets have been developed in plants to control cellular activity as well as building novel functions[73–75]. Among the mushrooms, just one genotype of shiitake was examined. In order to enhance the quality and customize mushroom strains through well-established conversion and genome editing systems, CRISPR/Cas9, base editing, and duplex editing methods were utilized[75].

Because of the hard fungal cell wall, the introduction of CRISPR components, including Cas9 protein, guide RNA (gRNA), and repair templates, into mushrooms frequently involves protoplast transfection[76]. For instance, in A. bisporus, the protoplasts are prepared by enzymatic degradation of the cell wall, and the CRISPR machinery is delivered through transfection with polyethylene glycol (PEG). It has been successful at modifying browning, disease susceptibility, and substrate use genes. Polyphenol oxidase (PPO), catalyzing enzymatic browning, reducing the shelf life of button mushrooms[77]. In a pioneering work, a 70% reduction in enzymatic activity was achieved by the inactivation of the AbPPO1 gene using CRISPR/Cas9. Edited mushrooms stayed remarkably white for over 10 days after being harvested, but wild-type strains turned brown in just 3 days[76,77]. This innovation minimizes food waste and aligns with consumers preferring non-GMO products, since the edit involved no insertion of foreign DNA. Trichoderma sp. wreaks havoc in oyster mushroom farms, resulting in yield losses of up to 40% occasionally[78]. A 2022 study targeted the Chs3 gene encoding chitin synthase, which is crucial for maintaining fungal cell walls' structural integrity. CRISPR-edited Pleurotus strains had thickened cell walls, reducing Trichoderma colonization significantly by 60%. This curtails reliance on fungicides quite significantly, aligning with the eco-friendly farming practices preferred nowadays[79]. G. lucidum synthesizes anticancer triterpenes at low natural levels. Editing of the HMGR gene, a potential bottleneck in the mevalonate pathway, resulted in a 3.5-fold increase in triterpene production. The modified strain is used in the nutraceutical industry to produce high-purity extracts for adjuvant treatment of cancer, which is regarded as an indication for CRISPR to increase its pharmaceutical value[80]. Overexpression of a heat shock protein (VvHSP60) by CRISPR-Cas9-edited V. volvacea improves mycelium thermotolerance, supporting its growth in subtropical regions. This discovery could help support production in the face of global warming. Although it is still in its infancy, the CRISPR/Cas system has already shown great promise in advancing plant synthetic biology and crop breeding, opening up a new world of agricultural possibilities. Heritable chromosomal mutations in the megabase range, such as alterations and mutations, have been successfully formed in plants by researchers using CRISPR/Cas tools in several recent several studies[81].

With a doubling or tripling of farmers' revenue in a year, changes in technology for production and diversification have caused the global mushroom industry to develop exponentially[82]. A growing trend in mushroom content and shelf life enhancement is bio-fortification or value addition. As a result, the farmland for mushrooms has expanded greatly. In order to maximize the productivity, nutritional value, and therapeutic qualities of mushrooms, government research institutions and contemporary biotechnology labs are essential to the breeding process[67, 75]. CRISPR-edited mushrooms are experiencing barriers—particularly in geographic regions (e.g., the European Union) with tough genetically modified organisms (GMO) policies. For instance, the European Union classifies CRISPR-edited mushrooms as GMOs and requires extensive safety assessments, while India and China take a milder approach to transgene-free edits. Public perception remains a barrier, too; market surveys showed that 65% of European consumers avoid products labeled "GMO" due to safety concerns[83]. Transparent labeling and education are crucial to overcome this trust barrier. CRISPR may be able to raise the selenium level or vitamin D content in mushrooms to fight malnourishment[84]. In Lentinula edodes, it has already been found that genes for selenium assimilation can be discovered (SelD), which could be further ablated to yield selenium-rich shiitake mushrooms. Editing lignocellulolytic enzymes in Pleurotus spp. may enhance the capacity to degrade agricultural residues, complementing the circular economy. The introduction of drought-resistant genes (e.g., DREB2A) into mushrooms may allow their cultivation in desert areas to solve the problems of food security[85]. Great development prospects are likely for industry owners through these technical advancements and advantageous policies of the government. The Indian government provides help to entrepreneurs who wish to establish high-tech mushroom farms as commercial enterprises.

Government programs for high-tech mushroom production in India

-

The Indian government implements various programs to develop mushroom farming commercially alongside technological advancements for sustainable mass mushroom cultivation.

Mission for Integrated Development of Horticulture

-

The Mushroom Development Scheme within the Mission for Integrated Development of Horticulture (MIDH) provides financial assistance for mushroom spawn production units and the construction of compost facilities. The subsidy from MIDH for compost pasteurization systems can be up to ₹2.5 lakhs while the subsidy for spawn labs stands at ₹1 lakh[86]. Farmer-supported small-scale farms in Maharashtra received funding from MIDH to use CRISPR-modified Pleurotus sajor-caju strains which demonstrated faster substrate transformation through 30% improved lignocellulolytic enzymatic action[87]. The optimization of substrate decomposition through fungal enzyme (proteomic) profiling is achieved via systems biology approaches[88].

Startup India Seed Fund

-

The Startup India Seed Fund Scheme (SISFS) provides ₹20 lakhs to agritech startups developing IoT-based mushroom monitoring systems. The AI prediction application developed by MycoTech, based in Bengaluru, achieved a 92% accuracy rate in forecasting Calocybe indica production through substrate nutrient profiling[89]. The implementation of fungal chassis engineering fits the synthetic biology objective of achieving steady metabolite production[90].

Public awareness campaigns for mushroom consumption

Educational programs

-

"Mushroom for Health" Initiative: Through their training program which reached 50,000 farmers under the National Mushroom Development Board (NMDB), workshops on mushroom agriculture and its nutritional value increased per capita consumption by 18%. Tribal communities in Odisha received instruction on growing selenium-enriched Lentinula edodes, which helped them tackle regional malnutrition[91]. The scientific field of systems biology supports bio-fortification programs that utilize genomic research to discover genes such as 'selD' in L. edodes, which lead to selenium enrichment in mushrooms[92].

Social media campaigns

-

Google Trends (2023) revealed a 200% spike in search volumes as a result of the NMDB's TikTok campaign #PowerMushroom, which promoted Cordyceps militaris as an "energy mushroom," which involved a short informative video explanation of how cordycepin (a nucleoside analog) works by preventing the creation of viral RNA, based on a 2020 metabolomics study[93]. According to genetic research on polyphenol oxidase (PPO) gene silencing, the social media influencer, "MushroomManIndia" utilized Instagram to showcase Agaricus bisporus specimens that were altered via the use of CRISPR, extending their shelf life[94].

-

Metabolomics is often performed via mass spectrometry (MS) to examine the profiles of metabolic pathways that are important biosynthetic pathways governing temporal growth and development in plants. Despite laboratory experiments, relatively few studies have reported metabolic differences between cultivars and fungi. A strategy that combines omics studies could potentially provide a more powerful tool for understanding the molecular mechanisms of gene regulation and the related metabolism through the creation of a single pathway[95]. Alongside other nutrients, beech mushrooms contain amino acids, organic acids, nucleotides, and secondary metabolites, which are obtained from carbohydrates. The mushroom Hypsizygus marmoreus is popular in most East Asian communities for its extremely chewy texture, earthy flavor, and culinary and nutritional properties[96]. Surprisingly, the abovementioned attributes of the beech mushroom can be analyzed through its complex transcriptome and cryptic metabolome, which govern the various stages of the mushroom's growth and development. The system of computational biology is adapted to specific signature pathways with notable synergy in adaptation to different sizes of mushrooms, metabolite profiles, and differentially expressed genes (DEGs)[97].

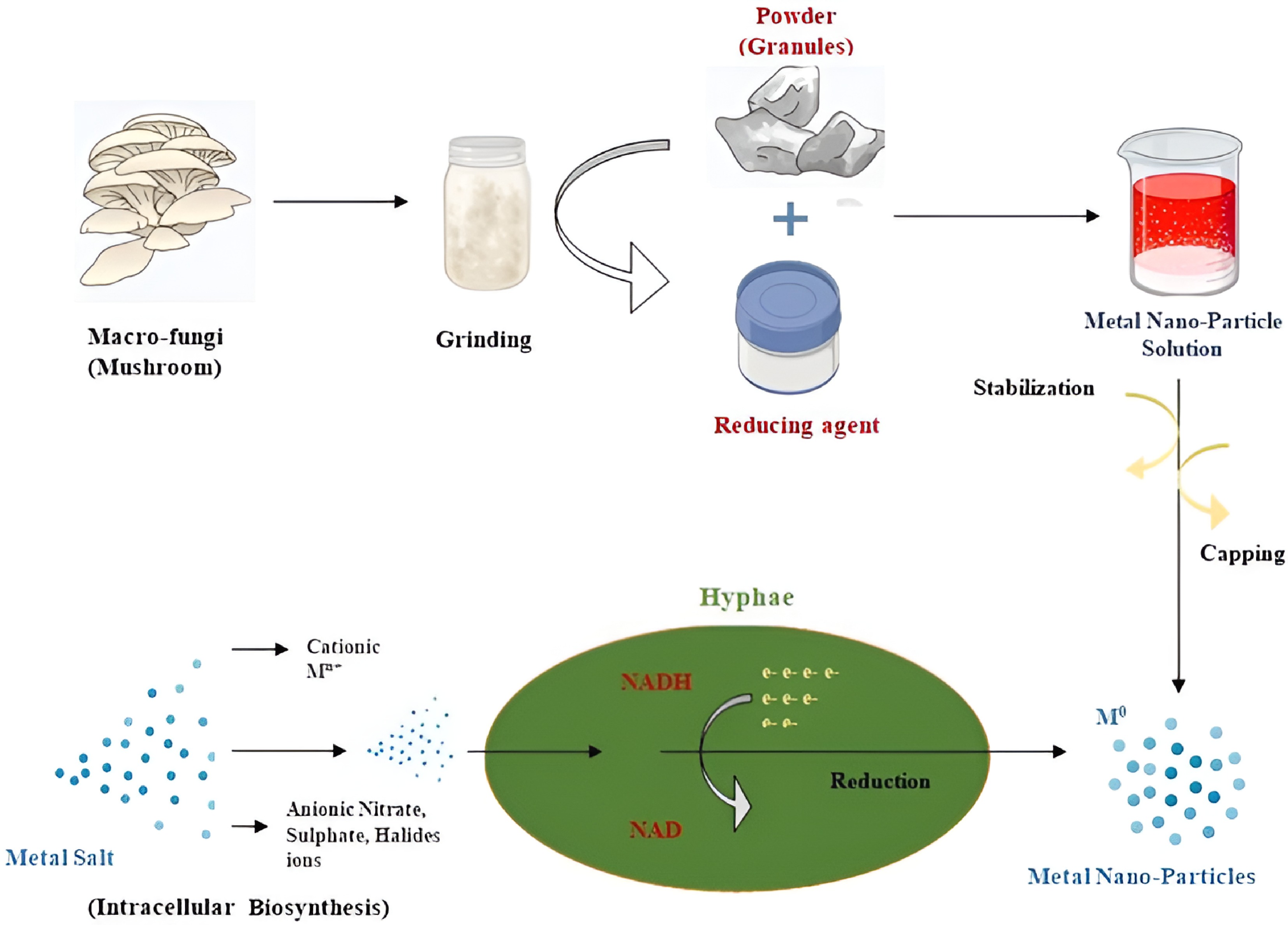

Recent years have seen a major increase in interest in the subject of myco-nanotechnology because of the possible applications of biosynthesized nanoparticles (NPs) made from mushrooms. The utilization of mushroom substrate is regarded as notable due to its high emission of macromolecules and digestive enzymes, which can serve as effective inhibiting molecules for the biogenic creation of different NPs through intravenous or cellular methods[98]. The NPs created by this technology have been demonstrated to be superior to those made using conventional biogenic methods because of their high yields, higher enzymatic activity, exceptional resistance to heavy metals, and quick recovery procedure[99]. These bio-molecules serve as reducing agents in addition to capping agents and stabilizers to transform metal ions such as Ag+, Au3+ and Zn2+ into zero-valent or nano-form (stable) NPs using sustainable methods of synthesis (redox reactions)[100]. For example, during the reduction of silver ions, Ganoderma lucidum produces quinones, which act as reducing agents to produce stable silver nanoparticles (AgNPs). The use of β-glucans as capping agents delivers two key benefits to NPs by enhancing compatibility and preventing particles from joining together. Protein profile analysis makes it feasible to identify key enzymes in these pathways, allowing for strain optimization and large-scale NP synthesis[101]. A simple approach for producing stable NPs without the use of organic solvents is ionic gelation, as shown in Fig. 4 below. The extracellular hyphae of mushrooms (~84%) or the intracellular hyphae of mushrooms (~16%) are the pathways by which mushroom-based NPs are synthesized. To generate NPs, for example, Pleurotus species are utilized extensively (~38%), and metallic NPs are the most often bio-synthesised, occurring in around 64% of instances[102]. Numerous mushroom genera, including Agaricus, Calocybe, Pleurotus, Ganoderma, Lentinula, and Volvariella, have been utilized in the production of metallic NPs, and their potential medical benefits, including antibacterial, antioxidant, anticancer, and anti-inflammatory properties, have been investigated. The applications of synthesized NPs derived from mushroom enzymes, including α-amylase, laccase, and other intermediates like polysaccharides and glucans may include water purification, bioremediation, bioleaching, and bio-catalysis[103].

Figure 4.

The (green) synthesis of metal nanoparticles from mushrooms is illustrated. Mushrooms are ground into powder for extracellular synthesis by adding metal salt solutions and reducing agents to the suspension solution being reduced, e.g., NADH and intracellular biosynthesis (bio-reduction and capping of metal cations such as Mn+ using fungal metabolism) are also types of this process. Created by biorender.com.

Different matrices, natural bio-active chemicals, extracts, and essential oils have all been produced for the encapsulation of medicines. In order to create metallic and nonmetallic NPs through biochemical processes using aqueous extracts that have been created or purified to manufacture such proteins/enzymes and polysaccharides, the mushroom mycelium and fruiting body have been utilized as essential bio-factors. These green chemistry techniques synthesize myco-NPs from various edible and medicinal mushrooms, including AuNPs, SeNPs, CdSNPs, PaNPs, AgNPs, ZnSNPs, and FeNPs[104]. The development of unique synthesis techniques can be aided by the many processes involved in the myco-synthesis of NPs employing several macro-fungi[105]. The section below explains the mushroom-assisted synthesis process of NPs together with real-world examples and data from systems biology research.

Mechanisms of action of mushroom-derived NPs

-

NP synthesis using mushrooms serves as an innovative collaboration between the research fields of mycology and nanotechnology. Bioactive compounds of mushroom consisting of β-glucans and laccase and peroxidases, along with phenolic acids, can naturally reduce and stabilize NPs during their synthesis. The extracellular development of AgNPs from Pleurotus ostreatus occurs through fungal reductases and quinones, which reduce Ag+ ions to generate antimicrobial spherical NPs with sizes ranging from 10 to 50 nm[106]. These NPs penetrate bacterial cell membranes through electrostatic forces, which results in the release of ions and destroys proteins[107]. NPs develop inside fungal cells because metal ions succeed in penetrating the cell wall to be reduced by enzymes and metabolites inside the cell. The production of NP solutions through mushroom extracts starts with extract preparation. Mushroom biomass from the fruiting bodies or mycelium is suspended in water or solvent for bioactive compounds extraction, followed by a metal salt (AgNO3, HAuCl4) mixture, and then the NP reduction and stabilization stages take place[108]. The bioactive compounds derived from Ganoderma, namely terpenoids, transform metal ions to NPs and simultaneously act as stabilizing agents to maintain their structural integrity.

Mechanistic insights and case studies

-

Selenium NPs (SeNPs) from Ganoderma lucidum activate the Nrf2/ARE pathway to increase hepatocytes' glutathione levels, which defends cells from ROS through antioxidant activity[109]. An analysis from 2023 that employed Ganoderma-SeNPs for rheumatoid arthritis treatment in laboratory mice confirmed that Ganoderma-SeNPs reduce inflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and Interleukin (IL)-6, through blocking the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) pathway, which supports their therapeutic application[110].

Breast cancer cell death occurs because mushroom NPs target the mitochondria, which triggers the sequential activation of caspase enzymatic cascades. The production of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) through the use of Schizophyllum family polysaccharides results in a material that binds to folate receptors on breast cancer cells and delivers 80% specific medication[111]. Research into Schizophyllum genes allowed scientists to discover essential β-glucan synthase genes that both stabilize NPs and establish a synthetic biology approach to the development of drug loading [112].

According to other research, Agaricus bisporus-derived drug delivery NPs release medications to tumor sites based on pH rather than targeting healthy tissues[110, 112]. Researchers found that by inhibiting the fungal ergosterol synthesis pathway, NPs reduced the amount of aflatoxin in food by 90%[113]. Another example involves the reduction of Ag+ into AgNPs, which occurs through the action of laccase enzymes present in a P. eryngii extract. According to the proteomics findings, the biological systems analysts verified laccase (Lac2) as the crucial enzyme functional in optimal condition at pH 5[114]. The antibacterial effectiveness of AgNPs against E. coli achieved 99% efficacy by causing membrane damage to bacterial cells.

-

Although techniques for growing mushrooms have improved over time to meet the growing demand, including spawn preparation, substrate sterilization, and pathogen control, the absence of automated systems that can alert growers when notable environmental changes occur in the mushroom cultivation chamber could potentially impede mushroom growth. Physically observing the climate can be extremely tedious and most warming, air conditioning (A/C), and humidity control systems have exceptionally uncertain mechanized control[115]. Soil moisture level and temperature are the primary ecological elements that influence mushroom production, as well as stem height and diameter, and cap size. Many mushroom species have multiple growth phases, each of which has its own set of environmental requirements. Specifically, for the white button mushroom, during the fruiting stage, the temperature should be kept between 15 and 22 °C, the relative humidity between 85% and 90%, and the carbon dioxide content below 1,000 μmol/mol[116].

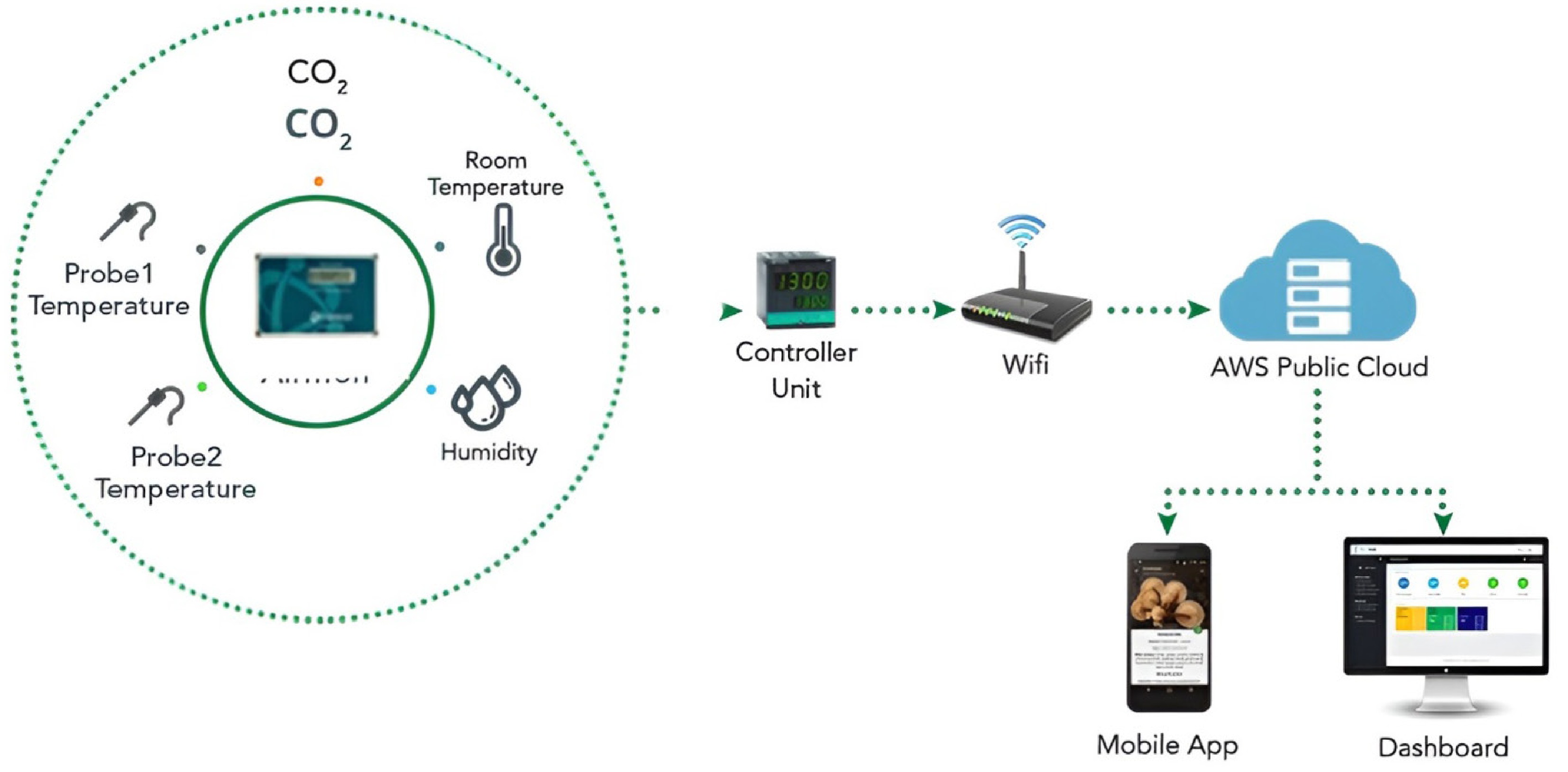

In order to reduce expenses through automation and enable users to track mushroom growth and conditions in real time from any location, a system of plug-detectors and IoT technologies is being integrated into mushroom farming procedures[117]. It offers a new platform that enables data transmission between computing devices, unique identity (UID) holders, digital or mechanical machines, animals, and humans without the need for human-to computer or human-to-human contact. A wireless network of sensor nodes (WSN) that can gather, transmit, and analyze data surrounding its perimeter is the main component of this IoT system[118]. It allows for problem-solving as well as the inception and management of machine-to-machine interactions. Additionally, in order to accomplish the goal of minimizing human involvement in the context of the IoT, the devices that are being targeted are fitted with transmitting devices and microcontrollers, which provide communication and setup using protocol stacks that identify interactions among the things being targeted[119]. The prototypes of new IoT projects can also be made possible by a variety of development boards, including microcontroller boards, system on chip (SoC) boards, and single-board computers (SBCs)[120]. Getting the greatest efficiency out of a mushroom farm requires step by step changes to ideal humidity, temperature, and CO2 depending on the development stage, which requires a robotized arrangement (or costly physical work)[121]. The variables of development are controlled in response to information from the sensors to follow an ideal development trend for the mushrooms at their particular growth phases. These phases, with the help of the AWS Public Cloud, which is a cloud computing model, provides farming infrastructure to operators via desktops and mobile phones, as shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5.

The mushroom monitoring solution is carried out through passive monitoring of mushroom farm, including seven stages that impact on the yield and quality of production[122].

Some have noted that the mushroom monitoring solution may risk inefficiency, as the process is not continuous and could face bias because of human power in the mushroom cultivation business. Day-to-day farming management depends on alarm set-up, carbon dioxide balance, checking the humidity level in different rooms, ensuring an appropriate temperature (especially in and out of mushroom bags), and other site management issues. This scientific model helps not only to grow mushrooms according to their temperature and soil texture, but also helps in state-wise farm programming[123]. Debate on new high-tech technologies starts and ends with power certainty, but the mushroom monitoring solution has attracted attention for its use in identifying problems related to soil and humidity proactively, reducing carbon emissions on a real-time basis[124]. Mushrooms require an ideal humidity level to develop. By the execution of high-tech solutions, human mediation will be less required and appropriate hygiene can be maintained during the mushroom development process[125]. This integrated design of IoT-based mushroom cultivation in a proper ambience, with a monitoring and management system developed for home-based farming, allows for remote control and monitoring of the growing parameters for mushrooms via a web and mobile application. Microcontrollers and relays attached to the heater, humidifier, and thermoelectric coolers provide environmental control[126]. Static images are loaded using Ajax through the JavaScript-based video player JSMpeg, which enables rapid video transmission (~40 to 50 ms) using Web Sockets to visualize the mushrooms' growth and development offsite. Using Dropbox API, the user is able to see and store the mushroom photographs remotely by taking screenshots of the webcam feed every 10–15 min, which are then automatically uploaded to Dropbox[127].

Integration of IoT in mushroom cultivation: case studies of smart monitoring

-

Machine learning algorithms allow operators to optimize conditions at 85%–90% humidity and < 1,000 ppm carbon dioxide specifically for Pleurotus ostreatus and Agaricus bisporus but IoT systems require wireless sensors to monitor growth conditions (DHT22 for measuring humidity and temperature and MQ-135 for carbon dioxide levels). Remote notifications for temperature abnormalities can be triggered through the integrated smartphone application feature of these systems. The usage of IoT devices presents ongoing problems with humidity-induced sensor drift and the financial burden needed for setting up the infrastructure. Through the implementation of edge computing with federated learning organizations, users can process data at their sites to boost rural farm scalability[117–119]. Smart monitoring systems built with IoT technology can help us minimize water consumption and energy usage, which results in better agricultural output alongside environmental protection.

• A Pleurotus eryngii farm in South Korea connected its operation to the AWS Cloud through IoT sensors that monitored CO2 levels with MQ-135 sensors and humidity readings with DHT22 sensors. Some studies showed machine learning algorithms adjusting CO2 (800–1,000 ppm) led to a 25% increase in production while cutting down energy usage by 18%[128].

• An IoT system implemented in Maharashtra (India) operated by Arduino demonstrated a 40% reduction in labor costs in addition to a 35% decrease in Agaricus bisporus contamination rates through automated temperature (16–20 °C) and humidity (85%–90%) control[129].

Loopholes in IoT-based monitoring systems

-

The main obstacle for IoT-based mushroom cultivation system involves sensor drift issues, which become severe in environments that maintain humidity at or above 95%. The prolonged time in humid environments results in moisture intruding into the sensors' components, which subsequently damages the electrical contacts through oxidation and results in condensation on the sensing surfaces[116–119]. For instance, DHT22 sensors often show signs of oxidation and condensation buildup when they are exposed to high humidity for too long, a case observed at one Pune-based Agaricus bisporus farm. For six months, these sensors produced readings outside the actual level by 15%–20%, showing 85%–90% humidity when the actual conditions were between 70% and 98%. This issue caused the climate control system to fail, which made the substrate in 30% of the grow bags dry and lost the farmer USD

${\$} $ Infrastructure expenses also make it harder for users to adopt the technology. An IoT setup for a 500-m2 farm in India using sensors (DHT22, MQ-135); microcontrollers (Arduino/Raspberry Pi); heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) automation; and connecting to the cloud costs around ₹2.5 lakhs, or roughly USD

${\$} $ ${\$} $ -

The production of biomedical and industrial mushroom NPs depends on bioactive substances containing polysaccharides and enzymes, since these materials show antimicrobial behavior and anticancer properties and act as antioxidants. An antibiotic containing standard drugs made from Ganoderma lucidum AgNPs proved effective against multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus strains in bacterial tests[107]. Lentinula edodes fights oxidative stress-related conditions through SeNPs that activate the Nrf2 antioxidant pathway for immune response enhancement, thus providing potential for preventing diabetes and cancer[109]. Wireless sensor networks utilizing real-time machine learning algorithms continuously monitor environmental elements which helps mitigate the risk throughout cultivation seasons. A team of South Korean researchers employed AI systems along with IoT devices to sustain ideal humidity conditions of 90% for Pleurotus eryngii mushrooms in their laboratory[110,121,127].

Advantages for human health and environmental impact

-

The delivery of targeted therapies through mushroom NPs produces benefits including lower side effects in comparison with synthetic drugs. Data from a research study demonstrated that chitosan NPs derived from the Schizophyllum family produced curcumin and reduced colorectal cancer tumor size by 60% through their pH-responsive capacity[130]. The pollutant remediation ability of Ganoderma-Fe3O4 NPs reaches 85% efficiency in capturing Pb2+ from water sources[129], and IoT systems applied to waste management turn agricultural byproducts into bio-energy, which reduces environmental emissions. Using CRISPR-edited Pleurotus sajor-caju, small farms increased their harvest by 25% and cut the time needed to prepare the growing material by 30% under India's MIDH initiative. The action demonstrated the value of CRISPR for policy by lowering labor expenses by 15% and leading state authorities to provide ₹5 cores for use in rural cooperatives[87]. Likewise, a South Korean farm that used IoT sensors (MQ-135 for CO2 and DHT22 for humidity) in conjunction with the AWS Cloud reported a 25% increase in yield as well as an 18% reduction in energy use as a result of machine learning-recommended temperature conditions. IoT functions at scale in industrial mushroom production, according to similar findings from 12 commercial farms in Southeast Asia[131]. Furthermore, strains of CRISPR-modified Ganoderma lucidum produce 2.5 times as many triterpenoid compounds, whereas RNA interference in Lentinula edodes decreased viral contamination by almost 40%. Table 3 helps explain the data.

Table 3. Synopsis of empirical findings.

Parameter Intervention Outcome Source Lentinan production CRISPR-enhanced L. edodes Increased by 40% Sakamoto et al.[61] IoT-driven yield optimization ML algorithms (CO2 control) 25% yield increase Choi et al.[128] Substrate colonization time CRISPR-edited P. sajor-caju Reduced by 30% Barh et al.[86] Heat tolerance 18% yield increase at 35 °C Bao et al.[65] Federated learning (IoT + ML) 42% fewer bacterial blotch cases Kathiria et al.[118] Limitations of myco-nanotechnology and IoT monitoring

-

Several barriers affect the implementation of myco-nanotechnology and IoT monitoring, including limitations in scalability, regulatory obstacles, and constraints in power usage. Mushroom products such as NPs can vary in size, shape, and effectiveness, depending on the mushroom species, what they are grown on and the conditions in which they are produced. For instances, batches of Pleurotus ostreatus produced AgNPs ranging between 10 and 50 nanometers, which resulted from fluctuations in laccase and reductase expression caused by changes in pH and temperature[98]. Similarly, the quantity of selenium in the culture medium determined the amount of ROS scavenging by SeNPs in biological samples[99]. The variation in NP output between mushroom species is caused by the naturally varying genetics and metabolism of fungi. Transcriptomic studies indicated that the CRISPR-modified strains exhibited a 15% variance in ligninase activity caused by epigenetics, which resulted in random breaking down of lignocellulose and the availability of NP precursors[24]. Concern for the environment is just as important, as laboratory tests showed that myco-NP (SeNP) discharges in water bodies resulted in reductions in the Daphnia population reaching up to 20%[132]. Commercialization is made more difficult by laws like the EU's REACH Amendment, as it means that fluid contamination tests last 90 days for NPs exceeding 1 g/L, which deters efforts to introduce Ganoderma lucidum-derived Fe3O4 NPs for use in soil remediation.

-

Mushroom production has experienced a transformation through the combination of systems biology technology and synthetic biology alongside IoT systems, which provide exact farming methods and high output and yield new possibilities such as myco-nanotechnology[133]. These modern innovations generate crucial moral problems, together with administrative hurdles that need to be solved for maintaining sustainable development and equal opportunity benefits as well as public confidence.

Ethical dilemmas

-

Data privacy in IoT-driven cultivation: IoT sensors assist farmers in monitoring temperature, humidity, and carbon dioxide levels in order to control crop resilience. Currently, EU regulations like the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) require individuals to give explicit consent before their data can be collected and used. Farmers face challenges because the GDPR rules do not protect agricultural IoT systems in poorer areas. A 2023 Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) study suggests that farmers should join together to form data cooperatives where they can collectively negotiate how their data are shared. By doing this, they can benefit from anonymous data usage platforms like India's e-Kisaan, while still owning their data[134]. This approach would help farmers make better use of their information without losing control over it.

Regulatory Frameworks

-

Nanotechnology and environmental safety: In 2023, the European Union introduced a rule called the REACH Amendment. It requires evaluation of the environmental toxicity of these particles if they are used in amounts over 1 g/L. For example, Ganoderma lucidum can produce iron oxide nanoparticles (Fe3O4), which are used for cleaning the soil[104–106]. These need to be tested for 90 days to see what effects they may have on earthworms and microorganisms in the soil.

Equity concerns

-

Patenting and innovation barriers: Local innovation is often hindered by company patents in myco-nanotechnology, which involves using mushrooms like Ganoderma to produce NPs. For instance, Mycotech Corp. holds a patent numbered WO2022345678[130]. However, using open-source licenses, such as those from the Open Mushroom Initiative, could open up access to these technologies.

-

The synthesis of NPs faces challenges due to different mushroom species being used, combined with growth environment factors and extraction procedures that lead to size differences and shape variations, as well as reduced functionality. The usage of NPs faces difficulties, in case of achieving mass production alongside potential risks to safety. Batch-to-batch variability in NPs' size necessitates CRISPR-based strain engineering[135]. The implementation of standardized global regulations about bio-nanomaterials creates delays for clinical and agricultural applications to progress. Small farmers experience financial barriers because IoT bioreactors, along with CRISPR-edited mushroom varieties, are expensive to acquire. The rejection of GMO fungus products by 65% of European consumers because of safety concerns regarding GMO fungi and NP toxicity is one of the main challenges for market expansion. The use of SeNPs improves crop resistance; however, their presence leads to microbial community disruptions, as observed in field experiments through reductions in soil bacteria populations of 25%[136]. Systems biology incorporates metabolic pathway optimization to address these issues. Cytochrome P450 genes that produce terpenoids were identified by a transcriptomic study of G. lucidum. Engineered Aspergillus strains with 40% more ligninase activity led to a better recovery of useful products from SMS. Using deep learning, experts could find the optimum situation for NP growth, and through applying machine learning to omics data, Agaricus bisporus contamination in Maharashtra dropped by 35%. Through AI-based analysis of large datasets, medicinal substances can be identified, ideal growing conditions can be predicted, and sophisticated mushroom strains can be developed quickly. Small-scale farmers working with restricted resources will benefit from democratization of precision agricultural technology, which can be achieved through developing affordable portable sensors for IoT-based systems[117–120]. Future integration of AI control and federated learning techniques, notably with JSMpeg tools, may lead to batch standardization to address aggregation-related problems. Applying technologies like the Open Mushroom Initiative and certain ITC-composting approaches will reduce myco-nanotechnology costs by growing business in sustainable ways. The circular economy uses farm waste as cheap materials for growing mushrooms and making NPs. Global standards and education will include creating ISO guidelines for assessing mushroom NPs and launching public programs to explain this technology[121]. These advancements aim to decrease the burning of farm waste and support eco-friendly mushroom growing and NP production.

-

Mushroom production has increased significantly in recent decades and is expected to continue to increase due to the need for high-quality food with less natural influences. After chemical extraction, the SMS can be used for one or two more rounds of mushroom production, after which the SMS can be used as a feedstock for compost, filler, or biofuel production. Future research will explore which applications of SMS are actually ecologically beneficial and useful, and how this can be advanced through the coordination of fungi and SMS production in agricultural and environmental frameworks. The focus should be on whether it is possible. Sustainable agriculture is poised to be transformed by the fusion of myco-nanotechnology with the IoT and systems biology. In order to research complex biological systems, the multidisciplinary area of systems biology needs to combine computer science, mathematics, and biology. It can assist researchers in creating fresh plans for raising crop yields, cutting back on fertilizer and pesticide use, and enhancing the sustainability of farming methods. Furthermore, an integrated IoT-based environmental surveillance and control system can be used to regulate temperature and humidity during the growing phase. The development of mushrooms throughout the fruiting period can also be measured using image processing techniques. People need to be involved in this process so that there is trust and so everyone works together, especially in projects involving CRISPR technology. Farmers should have control over their own data, and cooperatives can help them make decisions about how to use it. It is very important for small farms to follow the same rules as larger ones, but they may need financial assistance to meet the new requirements for using IoT and nanotechnology. By tackling these issues, the mushroom industry can take advantage of modern science and technology to achieve sustainable growth.

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Malakar S, Sutaoney P, Singh P, Chauhan NS; visualization, supervision: Singh P, Chauhan NS; writing – original draft: Malakar S, Sutaoney P, Singh P, Chauhan NS; writing – review & editing: Malakar S, Sutaoney P, Singh P, Shah K, Chauhan NS. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

NS Chauhan and Kamal Shah acknowledge Directorate Ayurveda, Yoga & Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy (AYUSH), the Department of Health & Family Welfare & Medical Education, Chhattisgarh, India and the Institute of Pharmaceutical Research, Ganeshi Lal Agrawal University, Mathura, India for providing the necessary facilities.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Malakar S, Sutaoney P, Singh P, Shah K, Chauhan NS. 2025. Systems biology for mushroom cultivation promoting quality life. Circular Agricultural Systems 5: e010 doi: 10.48130/cas-0025-0007

Systems biology for mushroom cultivation promoting quality life

- Received: 20 December 2024

- Revised: 03 June 2025

- Accepted: 03 July 2025

- Published online: 27 August 2025

Abstract: Mushroom farming has evolved from traditional methods to high-tech techniques using nanotechnology, and systems and synthetic biology. The three methods serve a key function by enabling waste transformation together with eco-friendly technology and ensuring food security. Mushroom production faces several hurdles that stem from achieving larger production quantities while enhancing 'Internet of Things' (IoT) systems' performance and dealing with ethical complexities.The review examines the development of mushroom biotechnology and its economic effects, as well as its impacts on society, alongside bioactive compound applications. The technology adopts system and synthetic biology approaches to maximize mushroom production. Mushroom cultivation benefits from CRISPR-edited mushroom strains, which shorten substrate colonization by 30% in addition to IoT systems that provide digital climate control. Scalability issues prevent mushroom-derived nanoparticles (such as Ag nanoparticles) from fully utilizing the antimicrobial efficacy. The commercialization of mushroom-derived nanoparticles faces delays due to 'Registration, Evaluation, Authorization, and Restriction of Chemicals' (REACH) regulations, alongside data ownership disputes and the stigma of genetically modified organisms (GMO) becoming ethical and regulatory concerns. The combination of artificial intelligence with CRISPR and IoT systems detects existing weaknesses to accomplish sustainable precision farming and environmentally friendly nanoparticle synthesis. Public awareness campaigns and high-tech mushroom schemes led by the government should reduce adoption gaps. In order to maximize the potential of fungi for sustainable agriculture and healthcare, future research needs to focus on ethical standards and cost-friendly IoT technology alongside metabolic information analyses.