-

With the rapid advancement of technology, urbanization has accelerated, resulting in a significant increase in the urban population and placing substantial pressure on urban traffic management[1,2]. The development of a city cannot be separated from efficient and intelligent traffic management. For this purpose, Intelligent transportation systems (ITS) were developed and have been widely adopted around the world[3,4]. The need for short-term traffic flow prediction has also become greater and more urgent with the rapid technological advancement and popular application of intelligent transportation systems[5].

Traffic flow prediction is a complex task. It aims to predict the future traffic state based on the input historical traffic state. Accurate traffic flow forecasting is essential for many intelligent transportation systems[6]. It helps traffic management implement interventions to alleviate traffic congestion[7], such as signalization control and manual road direction. Timely and reliable traffic flow information plays a remarkable role in alleviating traffic congestion, improving traffic operation efficiency, and supporting travel decision-making[8].

In addition to providing assistance in traffic management, traffic flow prediction also contributes to infrastructure development and resource allocation in cities[9]. The government can adjust urban development plans based on traffic flow during specific periods. The development of new roads and residential areas can optimize the utilization of road resources and help address the imbalance between the supply and demand of road capacity and travel demand.

Generally, the prevalent statistical approaches for traffic flow forecasting can be divided into parametric and non-parametric methods[10]. Traditional traffic flow prediction methods use parametric models to fit historical data and output predictions. However, forecasting real-time and accurate traffic flow is highly challenging because of the complex spatiotemporal dependencies inherent in traffic flow[11,12]. Parametric models underperform in prediction due to the complex spatial and temporal correlations of traffic flow. Early parametric models, such as Historical Average (HA)[13], Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA)[14], and Vector Autoregression (VAR)[15] provided the foundation for traffic prediction.

In recent years, with the rise of machine learning, many traffic flow prediction models have been developed based on machine learning. Machine learning models are capable of capturing complex spatiotemporal dependencies from massive traffic flow data to provide more accurate predictions. Additionally, data-driven methods do not require prior knowledge of the underlying system dynamics or equations, making them flexible and adaptable to different datasets and scenarios[16].

Classical machine learning models, such as linear regression, decision trees, and support vector machines, have been widely used for traffic flow prediction. However, traffic flow sequences are easily affected by external factors, such as unexpected accidents or manual interventions in traffic control[17], and classical machine learning models cannot capture complex spatiotemporal dependencies[18].

Deep learning approaches are not limited by the stationarity assumption and achieve better performance in time series prediction[19,20]. Some modern deep neural networks, such as Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN)[21−23], Long Short-Term Memory Networks (LSTM)[24−26], and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN)[27−29], have achieved outstanding results in traffic flow prediction[30]. These deep neural networks can extract complex spatiotemporal features from traffic flow data. They capture both temporal and spatial dependencies of traffic flow and output more accurate predictions. However, approaches based on CNNs and RNNs can only handle standard gridded data and neglect non-Euclidean correlations generated by complex road networks[31].

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) are a recent research hotspot. Graphs can represent many real-life objects, such as social relationships and knowledge graphs, among others. The traffic network is also a 'natural graph'[32,33]. In deep learning, graphs can be used to represent complex road network relationships, thus capturing the spatial dependencies of traffic flow. GCNs, when integrated with RNNs or Gated CNNs, achieve better performance in spatial and temporal modeling[34].

Despite the significant progress of deep learning in traffic flow prediction, there are still some challenges. For example, challenges remain in terms of model efficiency, transferability, abnormal event handling, and interpretability. This also brings many opportunities for future research.

Traffic congestion occurs all over the world, and traffic flow prediction is needed in many regions. However, these regions have different levels of economic development. A deep learning network requires a large number of parameters and long training times[35]. Some regions may not be able to provide enough computational power to train the model. Therefore, it makes sense to develop lightweight but effective traffic flow prediction models. Such models can be extended to economically underdeveloped regions to provide effective traffic flow prediction services, thus improving local traffic conditions.

In addition, due to regional economic conditions, certain regions may not be able to provide sufficient infrastructure to capture traffic flow data. Therefore, traffic flow data is lacking in these regions. The deficiency and low-quality training data may cause these models to fall into local minima[36]. Meanwhile, the traffic conditions in each region are influenced by local customs, culture, and road construction, and a traffic flow prediction model trained in a different region cannot be well adapted to the local traffic conditions. Therefore, it is necessary to develop an effective pre-training model and a domain-adaptive fine-tuning strategy.

While existing deep learning models show good prediction performance, their parameters still lack interpretability. As an auxiliary system for traffic management authorities to make decisions, traffic flow prediction models need to be sufficiently interpretable to make their predictions more trustworthy[37].

It is evident from the literature that there have been various surveys on traffic flow prediction. While most of these articles have investigated the role of machine learning (ML) in predicting traffic flow, the focus of this study differs from that of existing surveys.

● More concern is placed on open-source traffic flow prediction models that can be reproduced. Meanwhile, 15 publicly available datasets are reviewed, and details on how they can be used are provided, so that beginners can get started quickly.

● Although GNNs are used by most traffic flow prediction models, this review goes beyond GNNs to include new models from recent years. Examples include the Transformer model, pre-training models, and differential equation models.

● The future directions proposed are not limited to designing more complex models, but are more oriented towards real-world problems—for example, large-scale deployment, generalization capability of models, and multi-factor combination capability.

-

Here, the traffic flow prediction task is first described. The traffic flow prediction task aims to forecast future traffic conditions based on historical traffic flow data, taking into account a variety of external factors, such as weather and time of day[38]. In general, three common metrics for traffic flow prediction are traffic flow, traffic speed, and traffic density[33]. The choice of metric depends on the dataset employed.

Problem definition

-

Traffic flow rate is the total number of vehicles passing a given point during a specific time period[39]. It measures how many vehicles pass through a given point on the roadway and is critical to understanding the overall usage of the roadway network and identifying potential congestion points. Traffic speed is the average speed at which vehicles are detected traveling at a target location during the same time period[40]. Traffic speed indicates road conditions: high speed implies smooth traffic, while low speed implies congestion. Traffic density is the number of vehicles per unit length at a given time[41]. Higher traffic densities generally result in slower speeds and a higher likelihood of traffic jams, while lower densities indicate smoother traffic flow.

Traffic flow, traffic speed, and traffic density are all important metrics for characterizing road network performance[42]. In practice, it is common to use one of the three metrics for forecasting purposes due to data availability. For example, some datasets may provide detailed speed and flow information but lack density data, while others may provide all three metrics. The choice of metric usually depends on the specific requirements of the prediction task and data availability.

It is important to note that many data mining methods have been proposed due to increased data availability. Traffic flow prediction uses not only the metrics to be predicted, but also additional data. The most common type of additional data is periodic embedding[43]. Periodic embeddings are designed by extracting timestamps from traffic flow datasets. Common periodic embeddings include 'time of day', which represents the relative position of the current time within a day, and 'day of week', which represents the relative position of the current day within a week[44]. Periodic embedding allows the traffic flow prediction model to learn the periodicity of traffic flow. In addition, data such as weather and holidays[45] can also be incorporated into the traffic flow prediction model as embeddings.

Traffic flow prediction, as a key factor for measuring road traffic, can be grouped into coarse-grained and fine-grained types, which differ essentially in their applications to traffic planning and strategic decision-making. The main content of fine-grained traffic flow prediction is based on current and past traffic flow data, using time series analysis methods to predict future traffic flow over short-term horizons such as seconds, minutes, or half an hour[46].

Formally, the traffic prediction problem can be stated as follows: given a series of historical traffic data points, the objective is to predict traffic conditions at one or more future time steps[47]. This involves creating a predictive model that can accurately capture the temporal dependencies and patterns in the traffic data. The input to this model typically includes a sequence of traffic observations over a specified period, and the output is the forecasted traffic condition at a future time step. Thus, the traffic flow prediction task can be defined as follows:

Given the current time t, the prediction and history input windows is defined as follows: the prediction window of T' time steps is [t+1, t+2, ..., t+T'] and the history input window of T time steps time steps is [t−T+1, t−T+2, ..., t]. The ground truth of traffic flow is denoted as X, partitioned into historical data X = [Xt−T+1, Xt−T+2, ..., Xt] and labels Y = [Yt+1, Yt+2, ..., Yt+T']. The predicted output is denoted as

$ \hat{Y}=[{\hat{Y}}_{t+1},{\hat{Y}}_{t+2},\cdots ,{\hat{Y}}_{t+{T}^{{'}}}] $ $ \hat{Y}=f\left(\left[{X}_{t-T+1},{X}_{t-T+2},\dots ,{X}_{t}\right]\right)$ (1) The goal of the traffic flow prediction task is to design a model that takes historical data X as input and produces a set of predictions

$ \hat{Y} $ $ \hat{Y} $ ${\theta }^{\mathrm{*}}=\mathrm{arg}\underset{{\theta }^{\mathrm{*}}}{min} L\left({y}_{t+{T}^{{'}}},{\hat{y}}_{t+{T}^{{'}}};{\theta }^{\mathrm{*}}\right) $ (2) Performance metrics

-

After model training is complete, three metrics are typically used to evaluate predictive performance. They are Mean Absolute Error (MAE), Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE)[48]. The MAE is usually used as the model's loss function. The formulas of the three metrics are as Eqs (3)−(5):

$ {\mathrm{MAE}}=\dfrac{1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n} \left|{y}_{i}-{\hat{y}}_{i}\right| $ (3) $ {\mathrm{RMSE}}=\sqrt{\dfrac{1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n} {\left({y}_{i}-{\hat{y}}_{i}\right)}^{2}} $ (4) $ {\mathrm{MAPE}}=\dfrac{1}{n}\sum _{i=1}^{n} \left|\dfrac{{\hat{y}}_{i}-{y}_{i}}{{y}_{i}}\right|\times 100{\text{%}}$ (5) Model list

-

Table 1 shows a list of machine learning models for traffic flow prediction collected in this review. Specific details of these models, as published in the papers, are discussed in section Machine Learning for Traffic Flow Prediction, including research gaps and innovations.

Table 1. Model list.

Model Tag Source Year DCRNN[49] RNN/GNN ICLR 2018 2018 STGCN[50] CNN/GCN IJCAI 2018 2018 GraphWaveNet[51] TCN/GCN IJCAI 2019 2019 STSGCN[52] GCN AAAI 2020 2020 STAWnet[53] TCN IET intelligent transport systems 2021 ST-SSL[54] GCN AAAI 2023 2023 MegaCRN[55] RNN/GCN AAAI 2023 2023 D2STGNN[56] CNN/GCN VLDB 2022 2022 DDGCRN[57] GCN Pattern recognition 2023 RGDAN[58] GAT Neural networks 2024 STWave[59] GAT ICDE 2023 2023 STAEformer[60] Transformer CIKM 2023 2023 PDFormer[61] Transformer AAAI 2023 2023 STEP[62] Pre-training SIGKDD 2022 2022 STDMAE[63] Pre-training IJCAI 2024 2024 STG-NCDE[64] Differential equations AAAI 2022 2022 STG-NRDE[65] Differential equations ACM transactions on intelligent systems and technology 2023 -

In this section, the 15 datasets used in the collected papers are summarized. For each dataset, the following information is provided: metric types, time range, number of sensors, number of road edges, sample rate, and zero value rate. In addition to conventional loop detector data, recent studies[54,66] have increasingly utilized grid-based datasets, commonly used in trajectory prediction tasks. These datasets are commonly employed as baselines in experiments. An overview of the datasets is given in Table 2.

Table 2. Datasets overview.

Dataset Nodes Edges Time range Sample rate Zero value rate Type METR-LA 207 1,515 2012/03/01−2012/06/30 5 min 7.581% Speed PEMS-BAY 325 2,369 2017/01/01−2017/05/31 5 min 4.906% Speed PeMSD7(M) 228 1,664 2012/05/01−2012/06/30 5 min 0.10% Speed PeMSD7(L) 1,026 14,534 2012/05/01−2016/06/30 5 min 0.50% Speed PEMS03 358 546 2018/09/01−2018/11/30 5 min 5.102% Flow PEMS04 307 338 2018/01/01−2018/02/28 5 min 5.730% Flow PEMS07 883 865 2017/01/05−2017/08/06 5 min 5.028% Flow PEMS08 170 276 2016/07/01−2016/08/31 5 min 5.070% Flow CA 8,600 201,363 2017/01/01−2021/12/31 15 min 5.869% Flow GLA 3,834 98,703 2017/01/01−2021/12/31 15 min 5.712% Flow GBA 2,352 61,246 2017/01/01−2021/12/31 15 min 5.719% Flow SD 716 17,319 2017/01/01−2021/12/31 15 min 5.845% Flow NYC-taxi 16*12 − 2016/01/01−2016/02/29 30 min 48.63% Inflow/outflow NYC-bike 14*8 − 2016/08/01−2016/09/29 30 min 52.55% Inflow/outflow SZ-taxi 156 532 2015/01/01−2015/01/31 15 min 26.57% Speed Data preprocessing

-

Most machine learning models are implemented in the TensorFlow[2] or PyTorch[67] frameworks. The format of the dataset is usually NPZ (Numpy format) or CSV (Comma-Separated Values) and can be read using Pandas or Numpy. In general, the common dataset's shape is (TimeStep, Node). The first dimension corresponds to time steps, and the second dimension corresponds to nodes. Some datasets may contain multiple channels, such as flow, speed, and density. The shape of such a dataset typically has shape (TimeStep, Node, Channel).

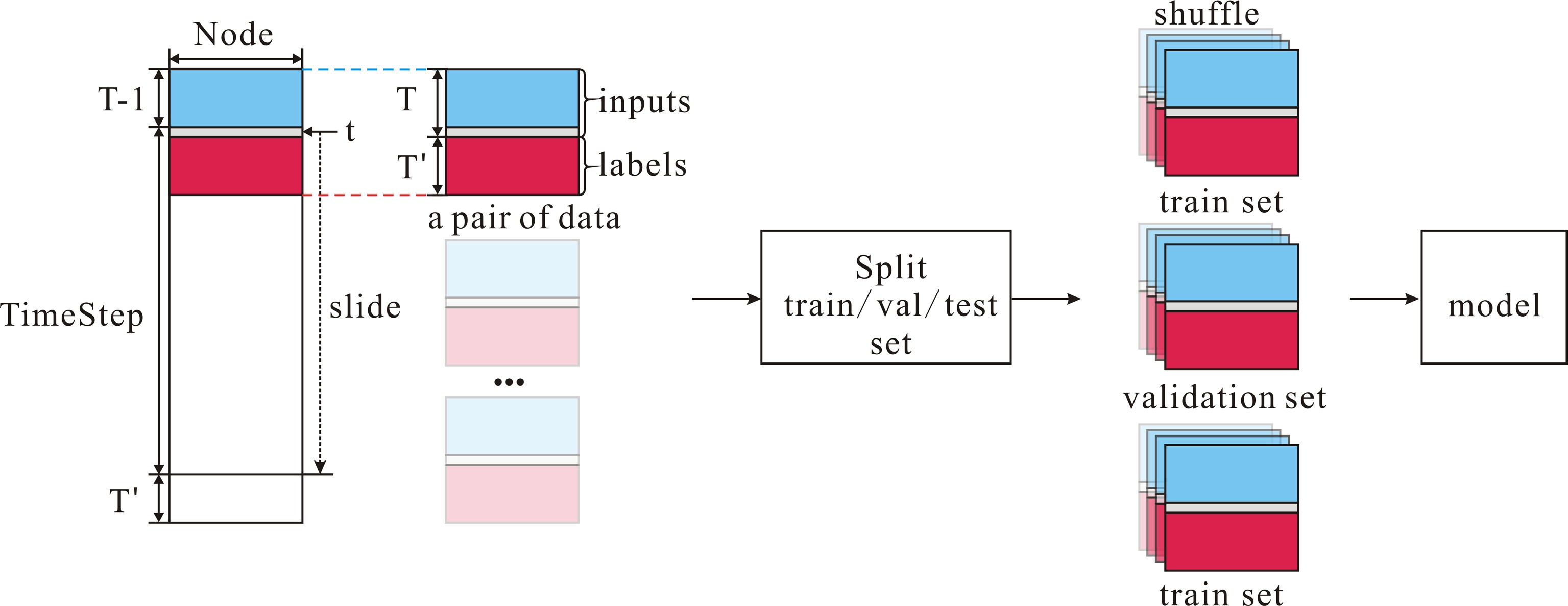

To generate the inputs and labels for the traffic flow prediction model, a pointer t is first initialized. Depending on the history window T and prediction window T', the pointer t traverses the first dimension (time steps) between [T, End−T']. At each time step, the traffic flow data of [t−T+1, t] is used as input, and the traffic flow data of [t+1, t+T'] is used as the corresponding label. After generating all the input-label pairs, the dataset is generally split into training, validation, and test sets in a 6:2:2 ratio. The dataloader fetches a batch of data pairs at a time according to the configuration, and the training set is shuffled during fetching. Finally, the dataset is fed into the model for training. The shape of a batch of data is generally [B, N, T, C],where B is batch size, N is the number of nodes, T is the length of the time series, and C is the number of channels. Different models may have different processing formats and split ratios, depending on the specific model implementation. The specific data preprocessing process is shown in Fig. 1.

-

Dougherty et al.[68] was one of the first efforts to use neural networks for traffic flow prediction. Vlahogianni et al.[69] used genetic algorithms (GA) to tune the neural networks. Zheng et al.70] combined conditional probability and Bayesian estimation and use multiple neural network predictors. Chan et al.[71] employed the hybrid exponential smoothing method and the Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) algorithm to process traffic flow data, aiming to improve the generalization capabilities of the model. This provided opportunities for migratory learning of models. Davis & Nihan[72] proposed a k-nearest neighbor (K-NN) approach to predict traffic flow. Cai et al.[73] updated the original K-NN model for traffic flow prediction which uses a spatiotemporal state matrix instead of a time series in K-NN.

Moreover, some models based on SVR, Support Vector Regression, are also used for traffic flow prediction. Castro-Neto et al.[74] proposed an online support vector machine for regression (OL-SVR). Su et al.[75] proposed an incremental support vector regression (ISVR) which uses an incremental learning approach to update the prediction function in real time.

These classic machine-learning models exhibited stronger performance than old statistical models over the past two decades. However, these models usually use simple structures, so they cannot be trained efficiently.

Deep learning model

-

About a decade ago, with the fast development of computational power, deep neural networks became more popular and have been applied in many applications[76]. Deep learning learns complicated features extracted from traffic flow information. Deep learning networks have many different network structures. For instance, RNNs can effectively capture the temporal dimension of traffic information, while CNNs can capture the spatial dimension[77]. Compared with classical machine learning models, deep neural network models have several advantages, but they also have some disadvantages. These deep learning models are generalizable. However, in traffic flow prediction, due to the strong spatiotemporal dependencies, specific models need to be designed to capture these dependencies for better prediction. Before the emergence of GNNs, researchers usually transformed urban road networks into Euclidean adjacency matrices and modeled them by combining convolution operations and residual units, which improved the ability of spatiotemporal feature extraction[78].

Graph convolutional network

-

In practice, the sensor nodes in the road are not distributed in a grid pattern, but irregularly distributed in the road network[79]. Recently, many researchers have begun to focus on graph neural networks[80]. The graph structure can well represent the various relationships in the road network[81]. Therefore, the model's forward propagation better reflects the actual structure of road networks. Graph neural networks overcome the shortcomings of previous studies that ignored the connectivity and globality of the network.

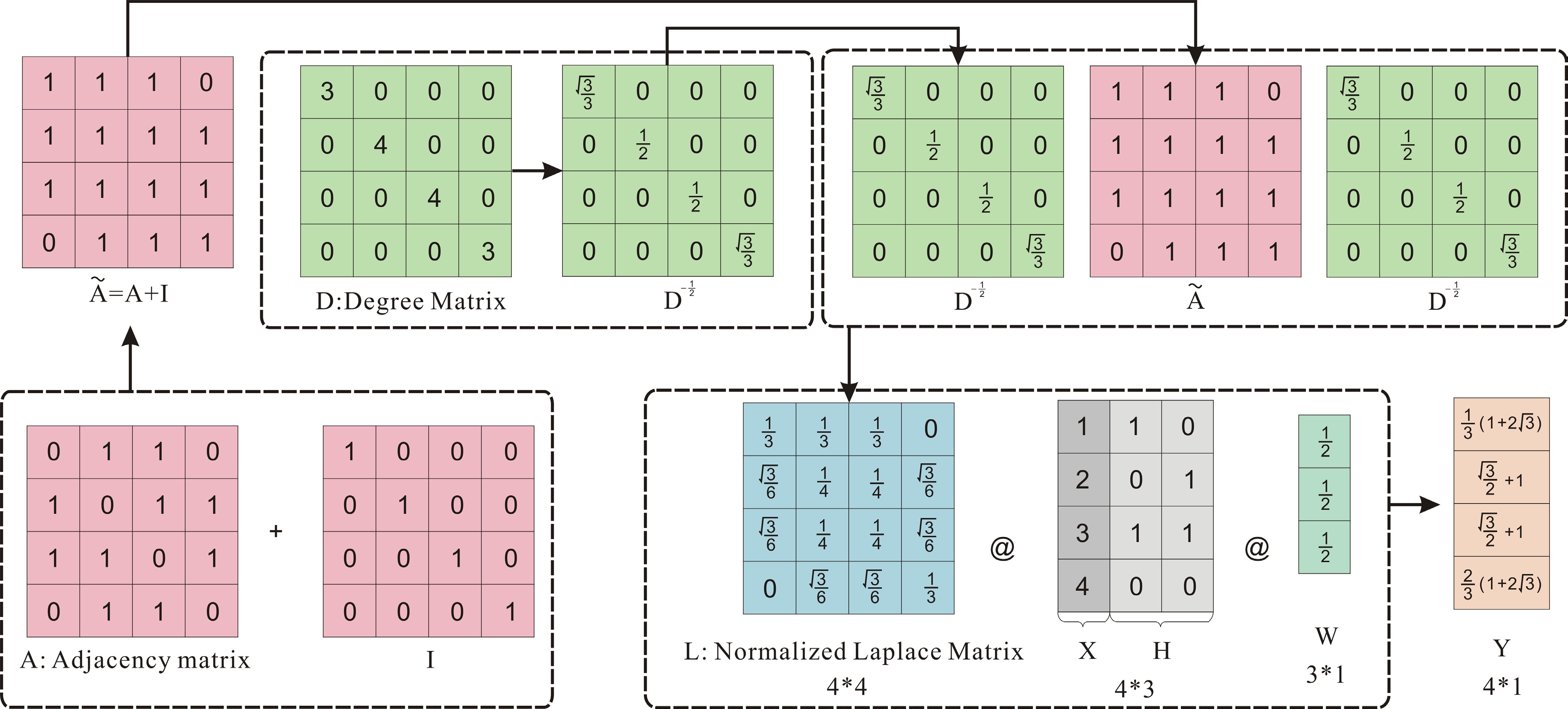

The basic process of graph neural networks is as follows: Consider a graph G = (V, E) with N nodes, with V, representing the nodes, and E, representing the edges. There is an adjacency matrix

$ A\in {\mathbb{R}}^{N\times N} $ $ X\in {\mathbb{R}}^{N\times 1} $ $ A $ $ X $ $ \tilde{\mathrm{A}}=\mathrm{A}+\mathrm{I} $ $ L={D}^{-\frac{1}{2}}\tilde{\mathrm{A}}{D}^{-\frac{1}{2}} $ $ D $ $ \tilde{\mathrm{A}} $ $ {D}^{-\frac{1}{2}} $ $ -\frac{1}{2} $ $ {D}^{-\frac{1}{2}}\tilde{\mathrm{A}}{D}^{-\frac{1}{2}} $ In forward propagation, the Laplacian matrix L is multiplied by the hidden states and input X. The weight matrix W is applied to the concatenated input X and hidden state H after the graph convolution. The graph convolution is simplified by the formula X = L[X

$\| $ $ \parallel $ $Y={[D}^{-\frac{1}{2}}\tilde{\mathrm{A}}{D}^{-\frac{1}{2}}]\left[\mathrm{X}\parallel \mathrm{H}\right]W$ (6) Figure 2 shows the process of graph convolution with a 4×4 adjacency matrix and 4×1 feature vector. Here, the symbol @ represents matrix multiplication.

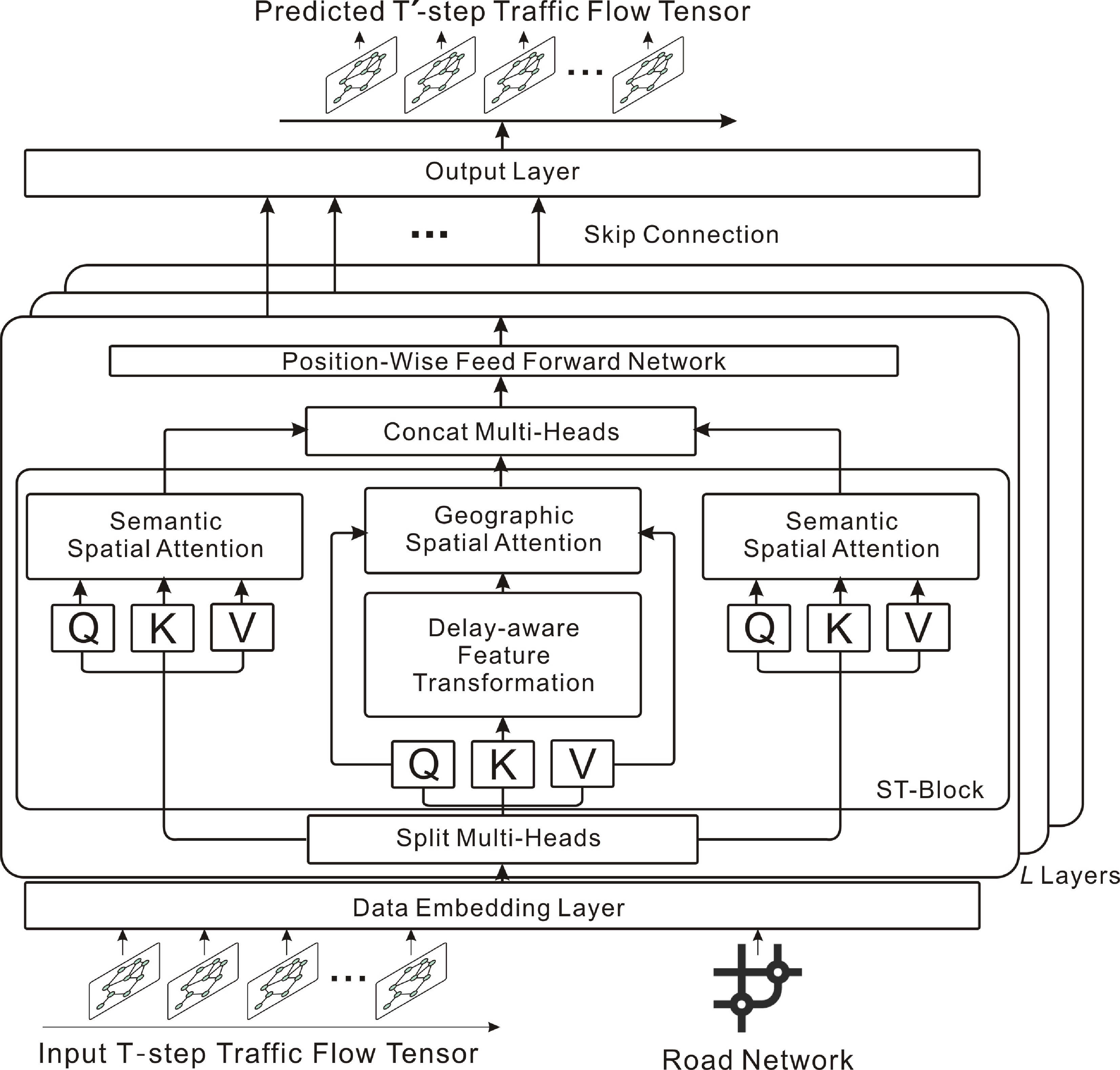

DCRNN[49], the Diffusion Convolutional Recurrent Neural Network, was one of the first efforts to use graph convolutional networks for traffic prediction. DCRNN uses a diffusion process to model the dynamics of traffic flow and proposes diffusion convolution to capture spatial dependencies. The model leverages recurrent neural networks (RNNs) to capture temporal dependencies. In particular, the matrix multiplication in the Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) is replaced by graph convolution to capture spatial correlations (Fig. 3).

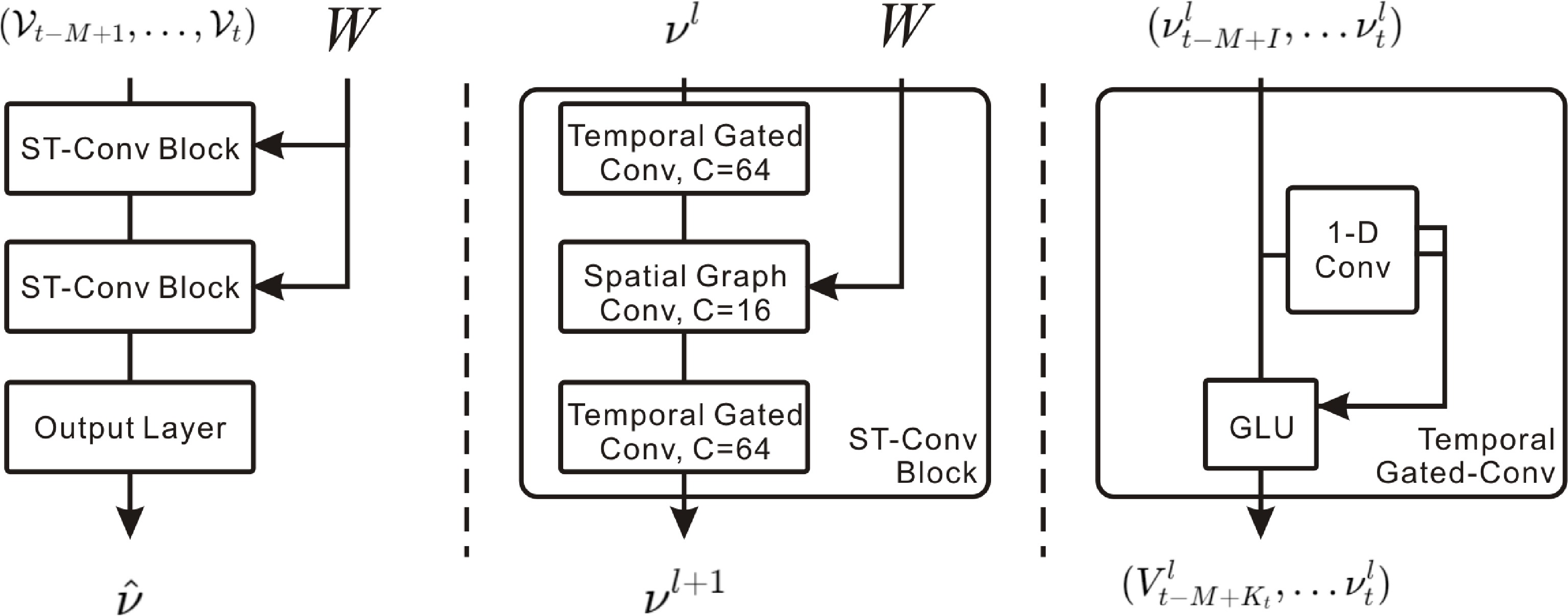

STGCN[50], the Spatiotemporal Graph Convolutional Network, consists of multiple spatiotemporal convolutional blocks, which alternate between gated sequence convolutional layers and spatial graph convolutional layers. The model employs the graph convolution operator '*G', which is based on spectral graph convolution, filtering the graph signal by the product of the signal and the kernel. The STGCN also employs a gated CNN to extract temporal features, implemented via 1-D causal convolution and gated linear units (GLUs) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

STGCN: combines spectral graph convolution for spatial features and gated causal CNN for temporal features.

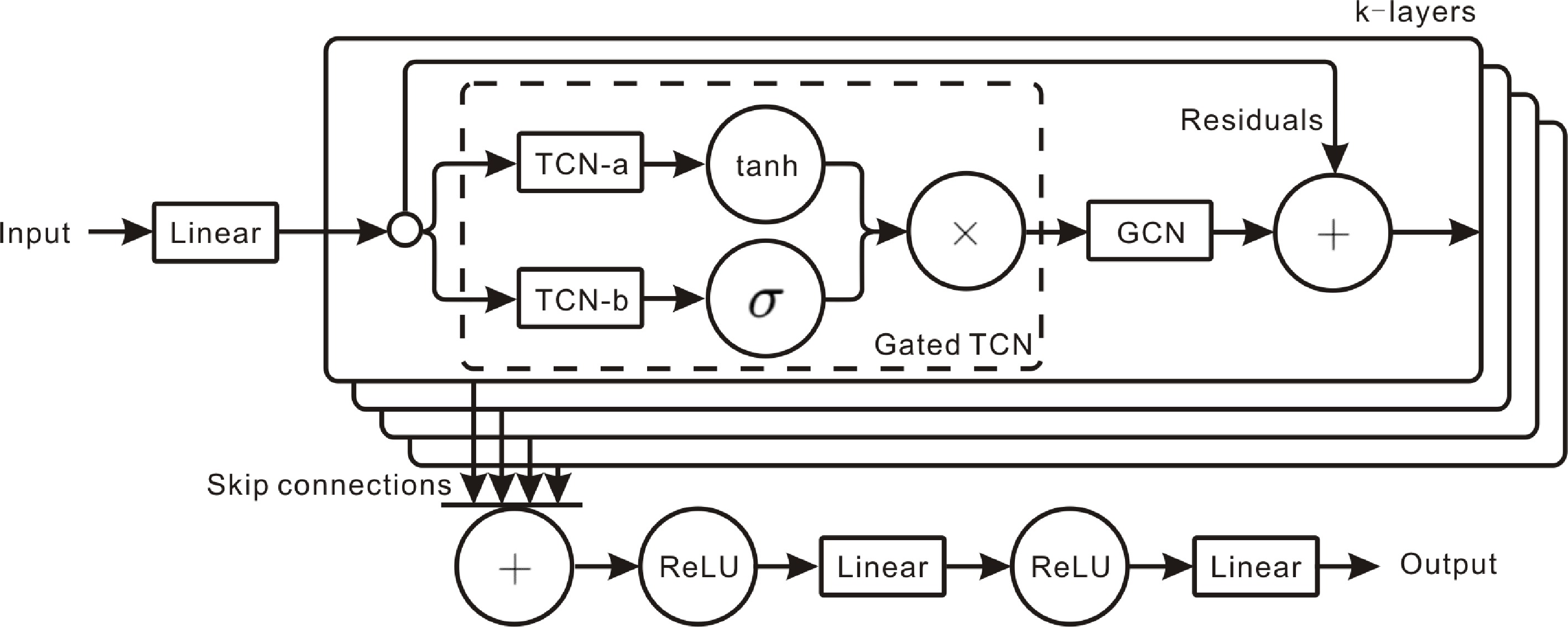

Graph WaveNet[51] learns from node embeddings and proposes a novel adaptive dependency matrix. Such a design can accurately capture hidden spatial dependencies in the data. This design addresses the issue that explicit graph structures do not necessarily reflect the true dependencies and may fail to capture actual relationships (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Graph WaveNet: adaptive adjacency captures spatial relations, while dilated causal convolution models temporal dynamics.

STSGCN[52] effectively captures complex local correlations in spatiotemporal network data through a well-designed spatiotemporal synchronization graph convolution mechanism, and includes a multi-module layer to account for data heterogeneity, improving prediction accuracy. The model captures local spatiotemporal correlations by constructing a local spatiotemporal graph using the spatiotemporal simultaneous graph convolution module (STSGCM), and models the heterogeneity across different time periods using a spatiotemporal simultaneous graph convolution layer (STSGCL) composed of multiple STSGCMs (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

STSGCM: captures local spatiotemporal correlations via a spatial-temporal synchronous graph convolution module.

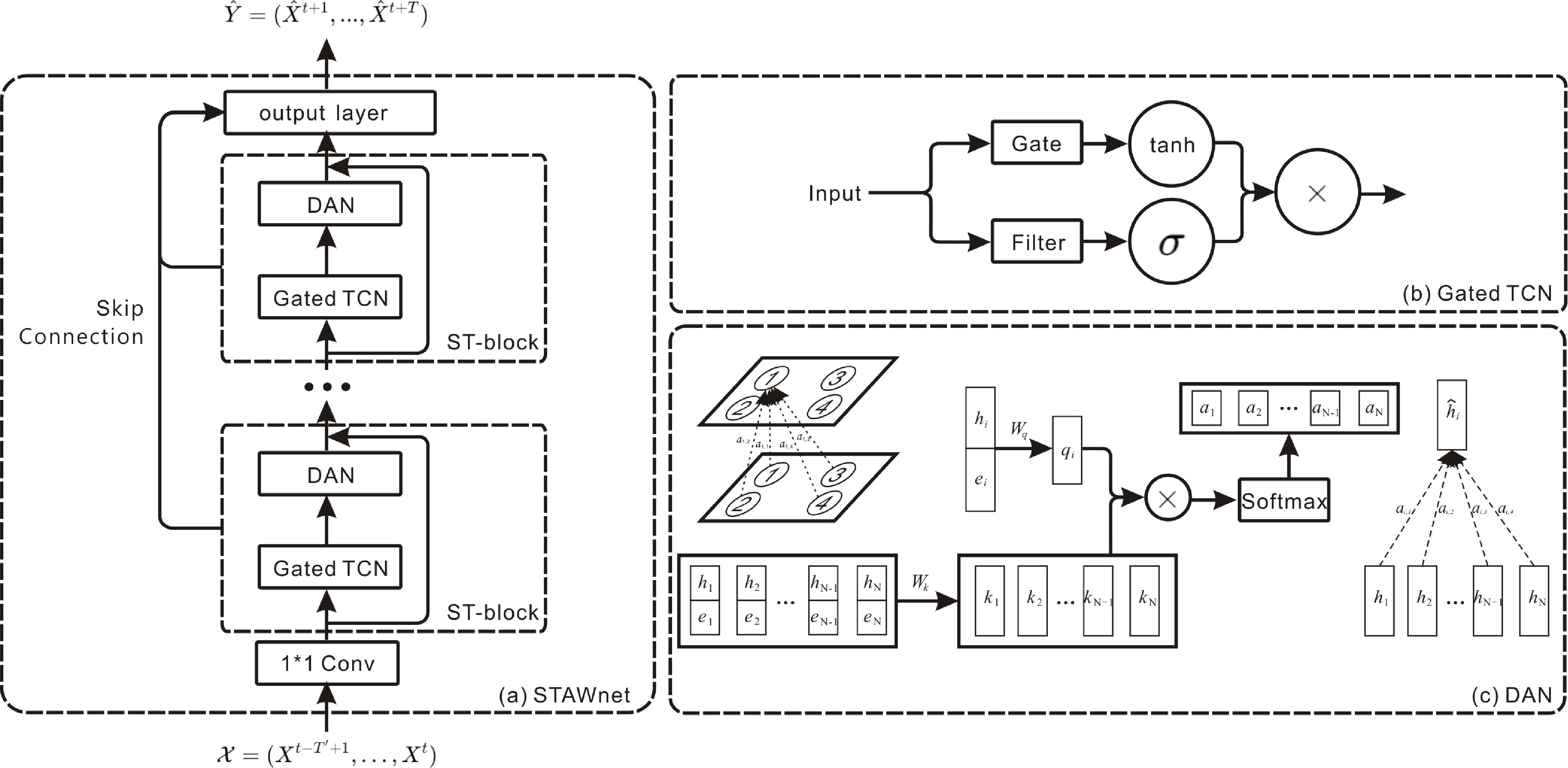

STAWnet[53] effectively captures the spatiotemporal dependencies in traffic conditions through a combination of temporal convolutions and attention mechanisms. STAWnet does not require a priori knowledge of the graph structure, instead capturing hidden spatial relationships through self-learned node embeddings. This design improves the flexibility of the model and allows it to be easily extended to other spatiotemporal forecasting tasks. STAWnet also incorporates a dynamic attention mechanism, which adjusts the weights of different nodes according to varying traffic conditions and spatial information (Fig. 7).

Figure 7.

STAWnet: self-learned node embeddings capture hidden spatial dependencies, while temporal convolution and dynamic attention capture temporal dynamics.

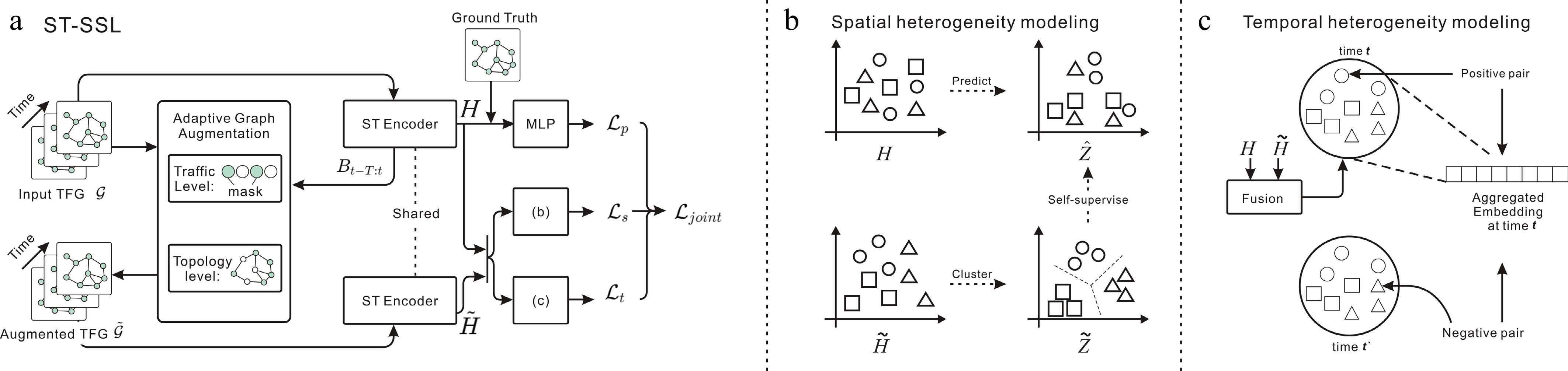

ST-SSL[54] integrates temporal and spatial convolutions to effectively encode spatiotemporal traffic patterns and incorporates two self-supervised learning tasks to enhance the main traffic prediction task by capturing spatial and temporal heterogeneity. The innovation of the ST-SSL framework lies in its adaptive augmentation of traffic flow graph data at both the attribute and structure levels. It also introduces a soft clustering paradigm to capture diverse spatial patterns among regions and a temporal self-supervised learning paradigm to maintain dedicated representations of temporal traffic dynamics. These mechanisms enable ST-SSL to effectively overcome the limitations of existing methods in handling spatial and temporal heterogeneity, particularly in scenarios with skewed regional traffic distributions and time-varying traffic patterns (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

ST-SSL: integrates temporal and spatial convolutions for spatiotemporal patterns, enhanced by self-supervised tasks for spatial-temporal heterogeneity.

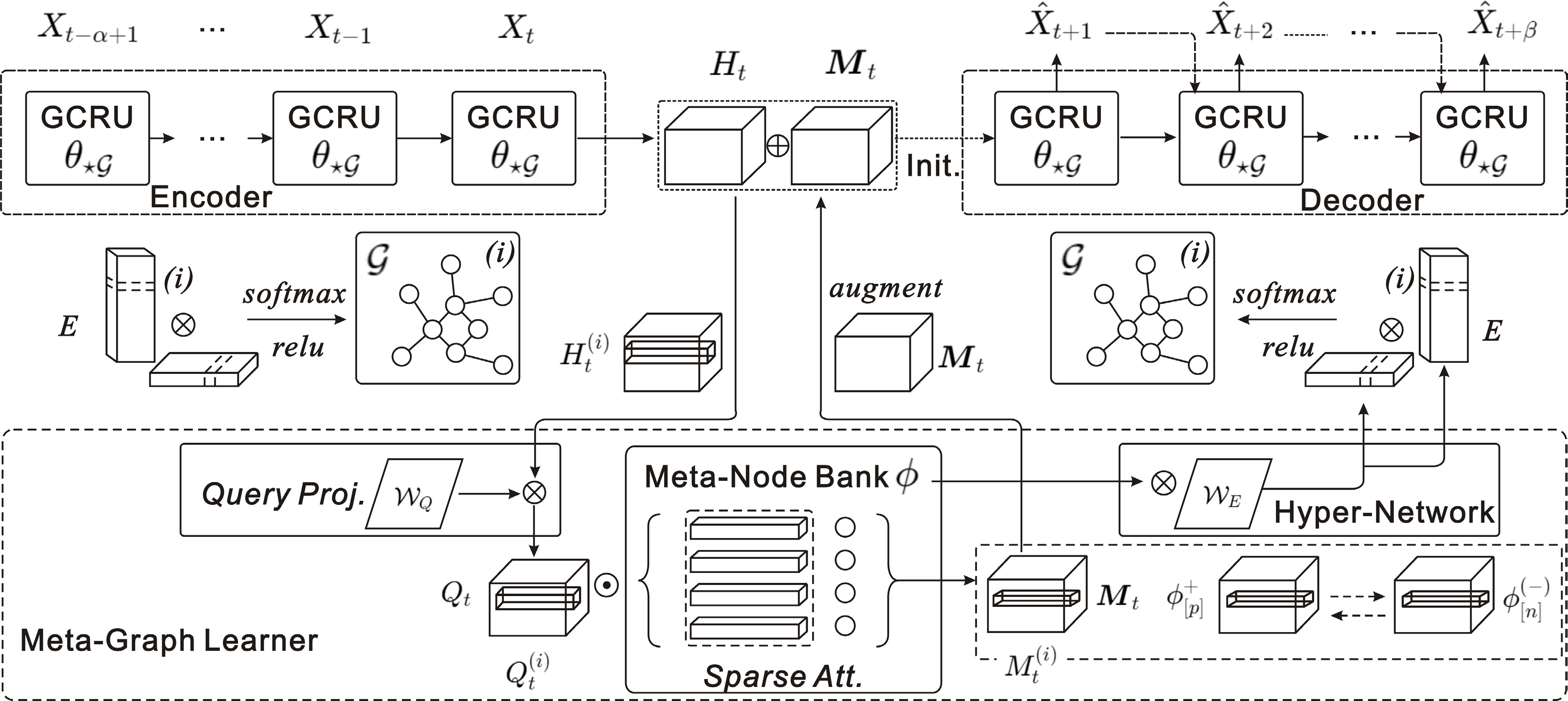

MegaCRN[55] integrates a meta-graph learner into a Graph Convolutional Recurrent Network (GCRN). This meta-graph learner is designed to dynamically generate node embeddings from an underlying meta-node library. Each node embedding is a multifaceted representation that encapsulates the temporal and spatial nuances of traffic dynamics. The meta-node library is a repository of memory items, each represented as a vector capturing the features of a typical traffic pattern. The Mega-Graph Learner queries this library to identify the memory item or prototype most similar to the current traffic state represented by the GCRN hidden state (Fig. 9).

Figure 9.

MegaCRN: meta-graph learner dynamically generates node embeddings capturing spatiotemporal nuances, integrated with a GCRN for prediction.

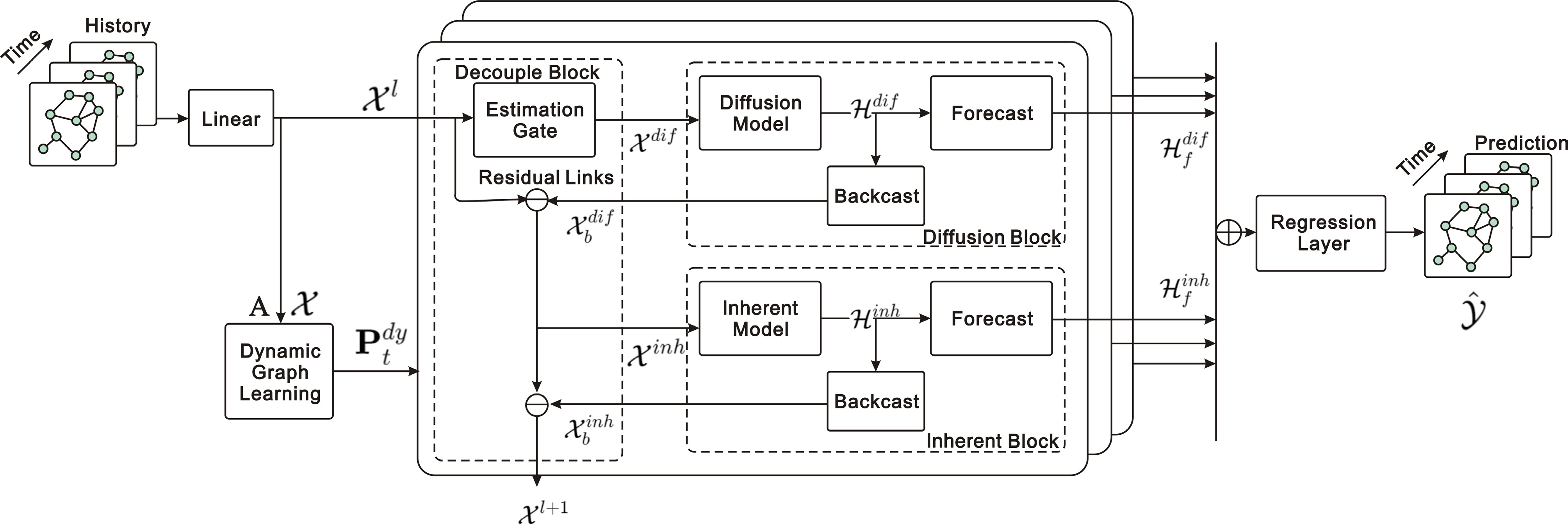

D2STGNN[56] addresses the limitations of conventional traffic prediction models by decoupling diffuse and intrinsic signals in traffic data. D2STGNN employs a decoupled spatiotemporal framework (DSTF) that integrates a dynamic graph learning module along with separate models for diffuse and intrinsic signals, thereby enhancing the modeling of spatiotemporal correlations (Fig. 10).

Figure 10.

D2STGNN: decouples diffuse and intrinsic signals via a decoupled spatiotemporal framework with dynamic graph learning.

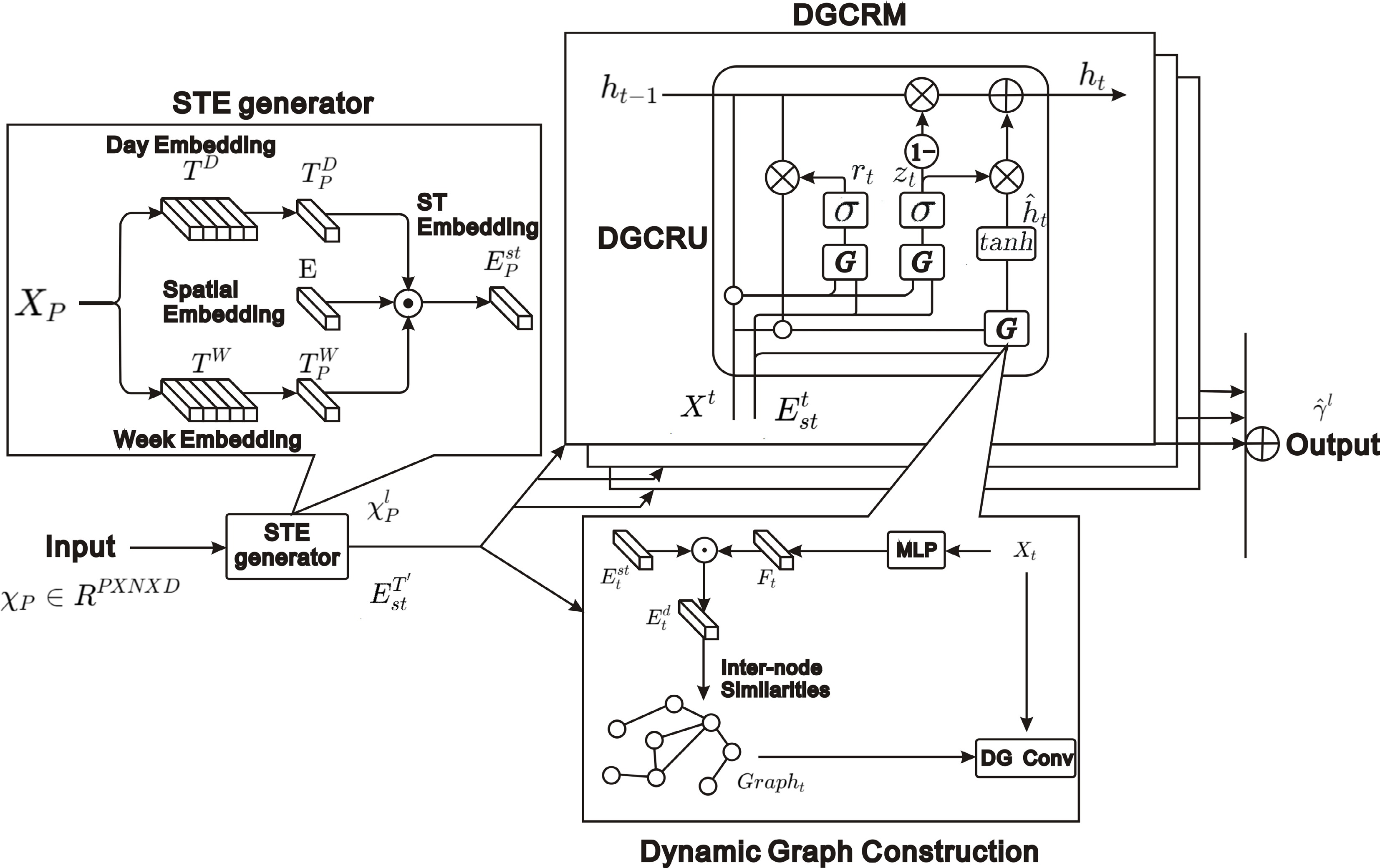

DDGCRN[57] dynamically generates graphs that capture the spatiotemporal dynamics of traffic flows and distinguishes between normal and abnormal traffic signals for a more nuanced understanding of traffic patterns. It adopts a data-driven approach to generate dynamic graphs from time-varying traffic signals, which are subsequently processed by the Dynamic Graph Convolutional Recursive Module (DGCRM) to extract salient spatiotemporal features. Furthermore, the model employs a segmented learning strategy that enhances training efficiency and reduces computational resource consumption during the initial training phase (Fig. 11).

Figure 11.

DDGCRN: dynamically generates graphs from traffic signals and uses DGCRM to capture spatiotemporal features efficiently.

RGDAN[58] integrates the Graph Diffusion Attention module and the Temporal Attention module. It employs a stochastically initialized Graph Attention Network (GAT) that does not rely on predefined node interactions, instead learning the attention weights directly from the data. This stochastic GAT, combined with an adaptive matrix, captures both local and global spatial dependencies, thereby providing a more accurate representation of traffic flow patterns. The Temporal Attention module is adept at identifying and learning from temporal patterns, ensuring that the predictive model is sensitive to temporal variations inherent in traffic flow (Fig. 12).

Figure 12.

RGDAN: random GAT with adaptive matrix captures spatial dependencies, while temporal attention captures time-related patterns.

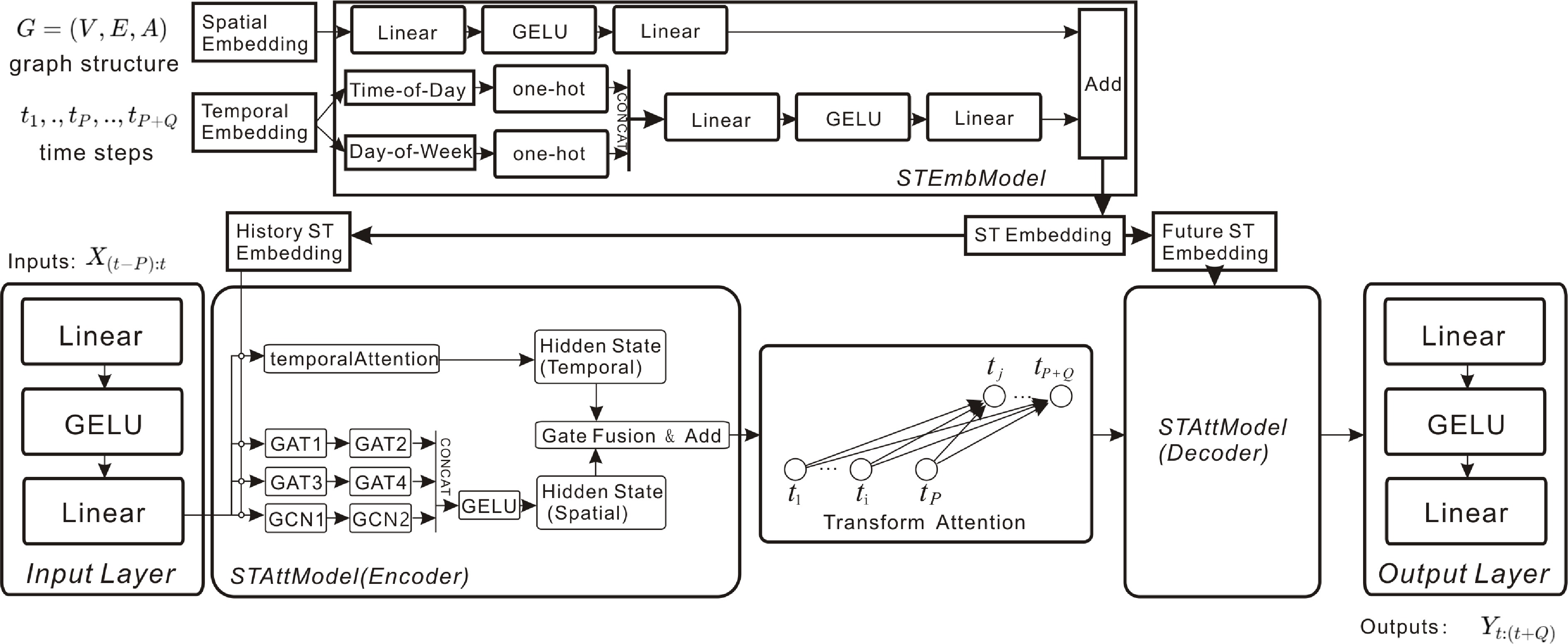

STWave[59] addresses the challenge of non-stationary traffic time series by adopting a disentangle-and-fuse approach. STWave decouples complex traffic data into stable trends and fluctuating events using the discrete wavelet transform (DWT), thereby mitigating the distribution shift problem. It then employs a dual-channel spatiotemporal network to separately model these components and integrates them for improved future traffic prediction. A key contribution is the introduction of an efficient Spectral Graph Attention Network (ESGAT) with a novel query sampling strategy and graph wavelet-based positional encoding. This design enhances the modeling of dynamic spatial correlations while reducing computational complexity (Fig. 13).

Figure 13.

STWave: decouples traffic series into trends and events with DWT, and uses dual-channel spatiotemporal network and ESGAT for modeling.

Transformer-based model

-

The Transformer model has revolutionized the field of Natural Language Processing (NLP) since it was proposed by Vaswani et al.[82] particularly excelling in tasks such as machine translation and text summarization. The core self-attention mechanism is able to capture long-distance dependencies in sequential data, thereby overcoming the limitations of traditional RNNs in processing long sequences. With the continuous advancement of deep learning, the Transformer architecture has gradually been introduced into other domains, including traffic flow prediction.

This subsection focuses on two types of Transformer-based models: the STAEFormer and the PDFormer. Both models have achieved remarkable results in the field of traffic flow prediction and have improved and extended the Transformer architecture from different aspects to better adapt to the characteristics of traffic data.

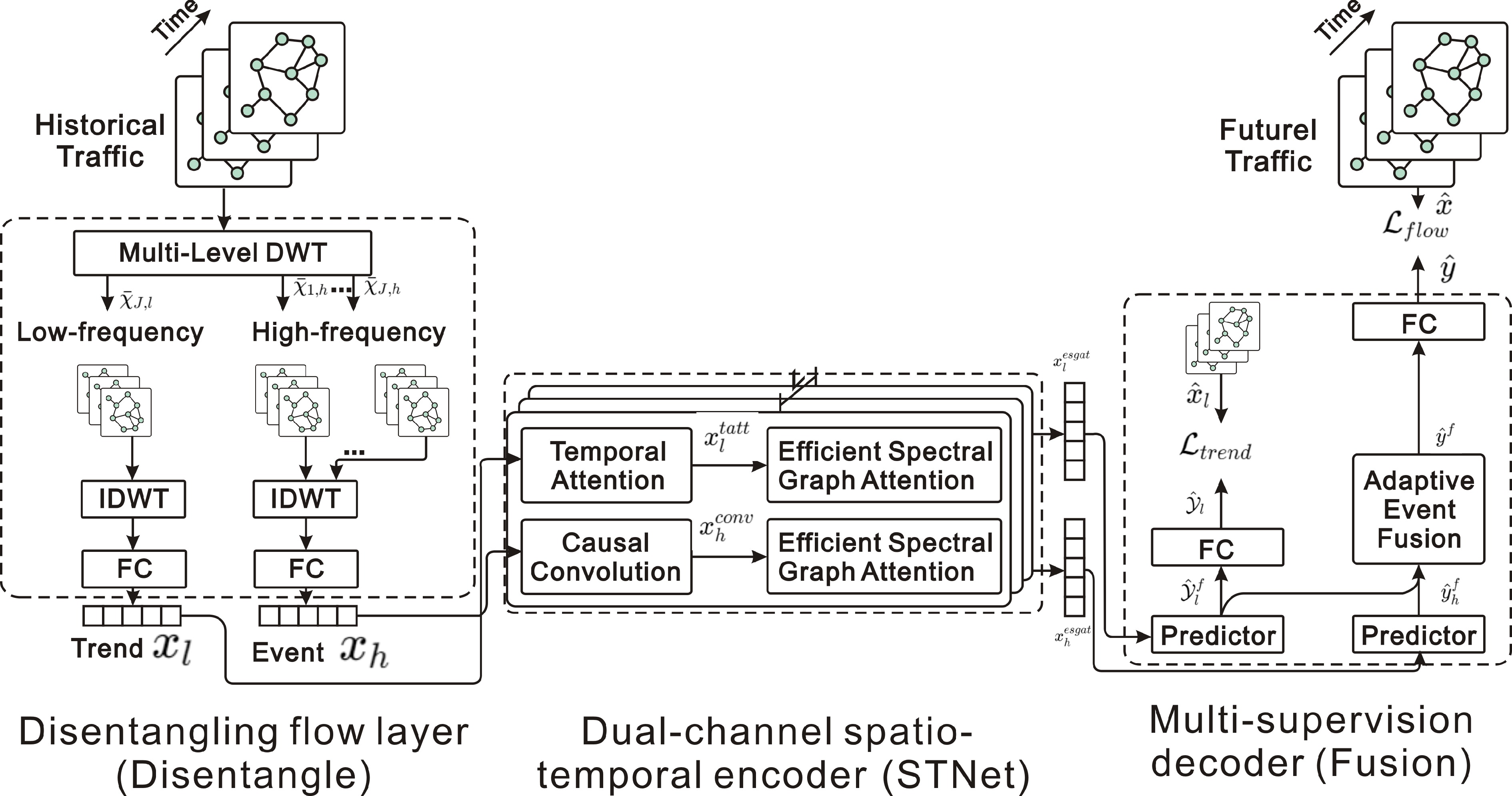

STAEFormer[60] leverages a simple yet effective spatiotemporal adaptive embedding technique to enhance the capabilities of vanilla Transformer models, achieving state-of-the-art performance. The key innovation lies in the model's ability to capture the complex spatiotemporal dynamics and chronological information inherent in traffic time series data, which has traditionally been a challenge for forecasting models. This work focuses on improving the representation of the input data rather than complicating the model architecture (Fig. 14).

Figure 14.

STAEFormer: spatiotemporal adaptive embedding enhances Transformer to capture complex spatiotemporal dynamics in traffic data.

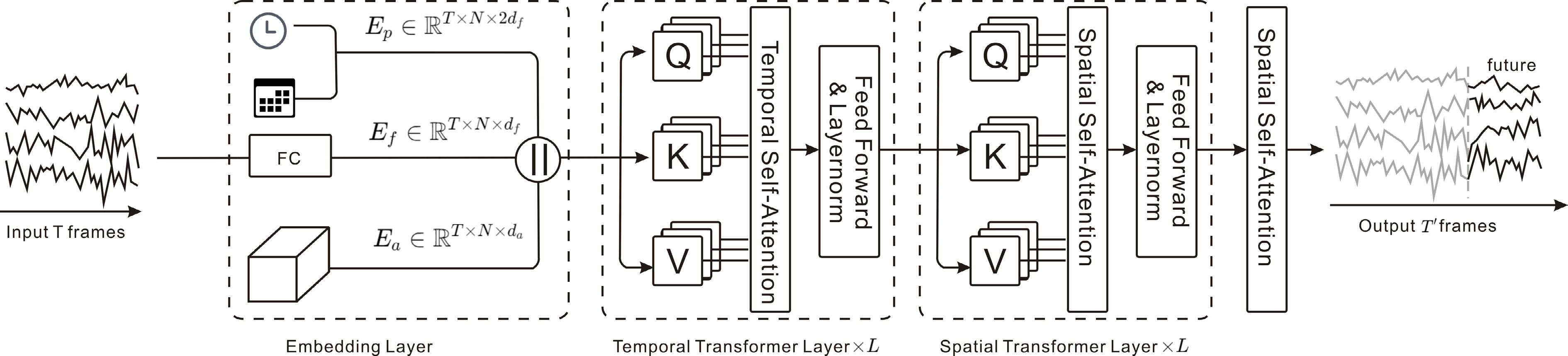

PDFormer[61] introduces a novel propagation delay-aware dynamic long-range Transformer specifically designed to address the complex spatial-temporal dependencies in traffic flow prediction. The model innovatively integrates a spatial self-attention module to capture dynamic spatial relationships, employs graph masking matrices to emphasize both short- and long-range spatial dependencies, and introduces a delay-aware feature transformation module to account for the time delay in traffic condition propagation. This comprehensive approach effectively models the temporal dynamics and spatial heterogeneities in traffic data, leading to improved accuracy and interpretability in traffic flow predictions (Fig. 15).

Figure 15.

PDFormer: spatial self-attention, graph masking, and delay-aware transformation model complex spatiotemporal dependencies.

Pre-training model

-

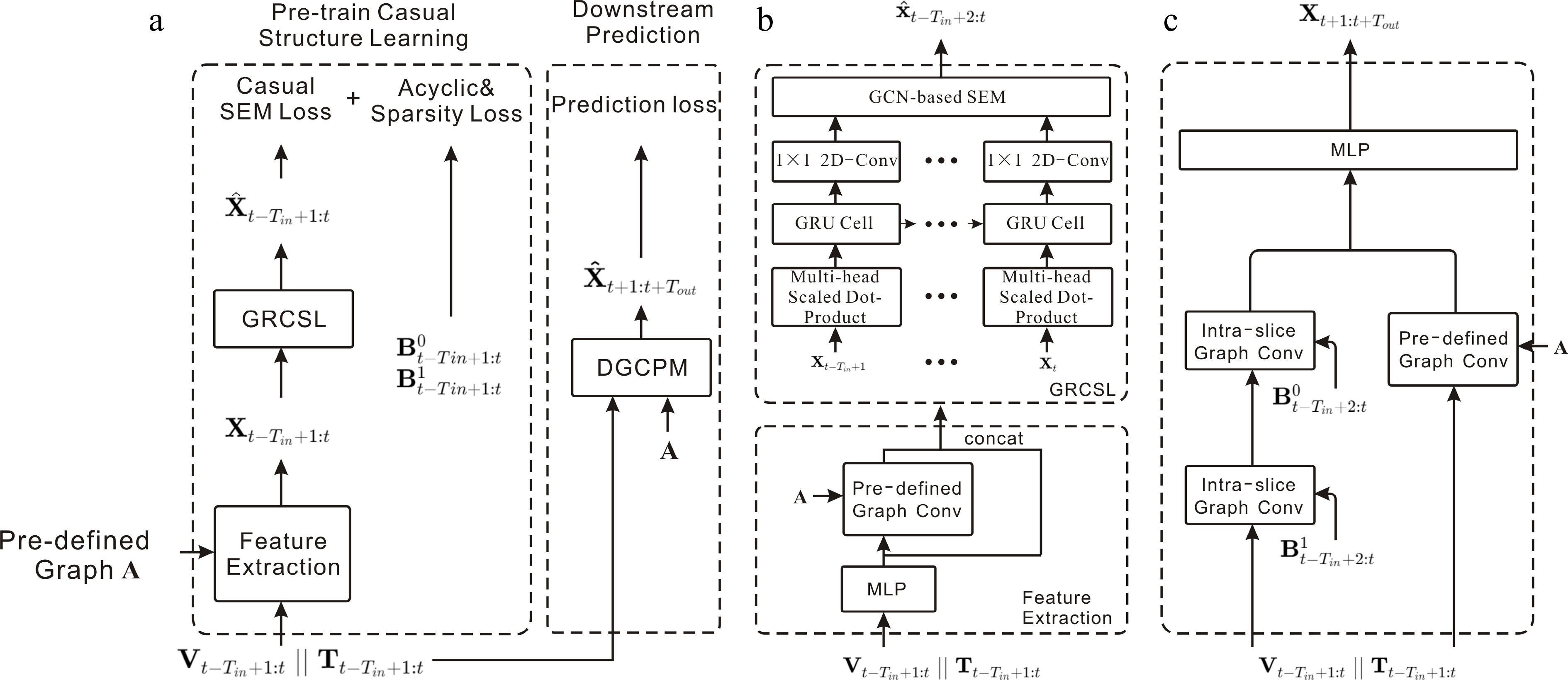

STEP[62], STGNN is enhanced by a scalable time series pre-training model, which is the first traffic flow prediction model to employ pre-training techniques. The motivation of STEP is based on STGNN. Although STGNN shows good performance in MTS prediction, it only considers short-term historical MTS data due to model complexity. To leverage long-term historical MTS data for analyzing temporal and spatial patterns, STEP proposes a novel framework. It introduces a pre-training model to efficiently learn segment-level representations from long-term historical MTS data, using these representations as context for STGNN (Fig. 16).

Figure 16.

STEP: Pre-training on long-term traffic sequences provides segment-level representations to enhance STGNN predictions.

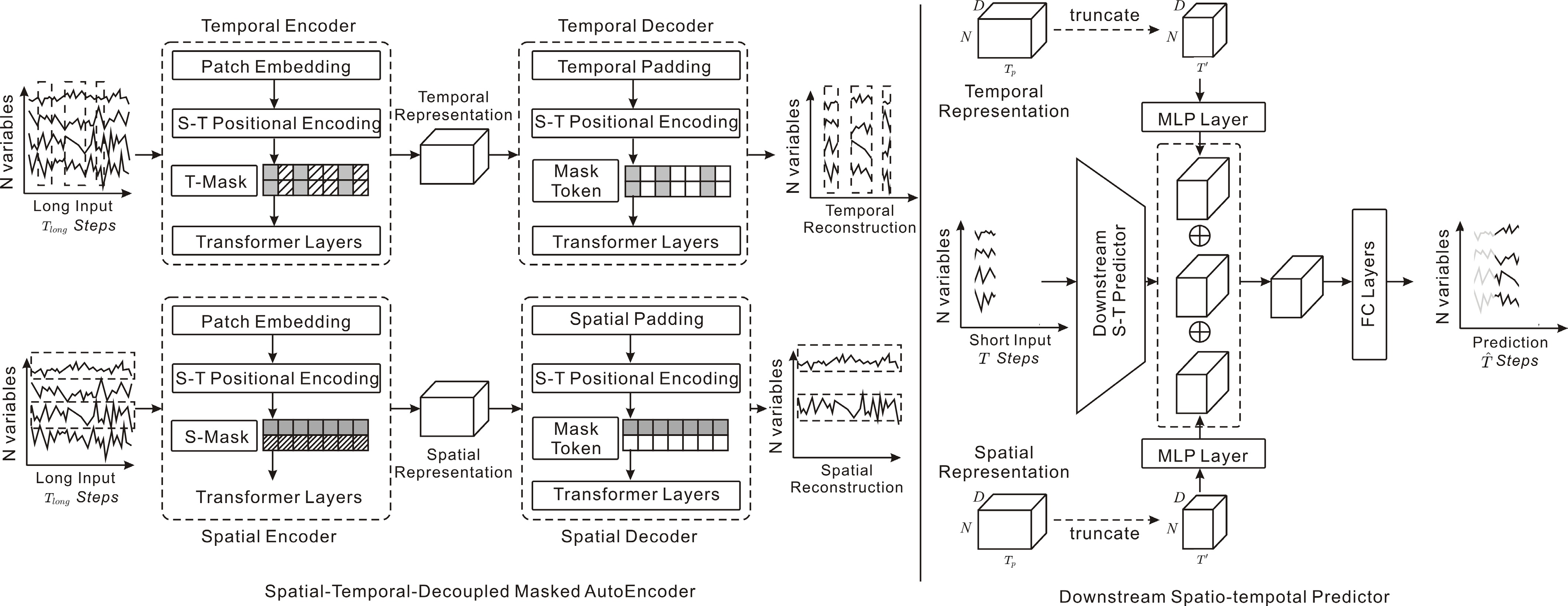

STD-MAE[63], short for Spatial-Temporal-Decoupled Masked Pre-training, shares the same motivation as STEP. The method aims to overcome the limitation of input series length. It employs two decoupled masked autoencoders to reconstruct spatiotemporal series along the spatial and temporal dimensions. Compared with STEP, STD-MAE introduces an additional pre-training step along the spatial dimension. By applying masking separately along the two dimensions, the model can effectively capture long-range heterogeneity in MTS data (Fig. 17).

Figure 17.

STD-MAE: Decoupled spatial-temporal masked autoencoders reconstruct sequences to capture long-range heterogeneity in traffic data.

These two pre-trained models have achieved good performance. The pre-training is designed to remove the limitation imposed by the length of the input sequence. More importantly, they are not constrained by the limitations of data sources. A wider range of data can be utilized for pre-training, rather than being restricted to traffic flow data from a single area.

Differential equations model

-

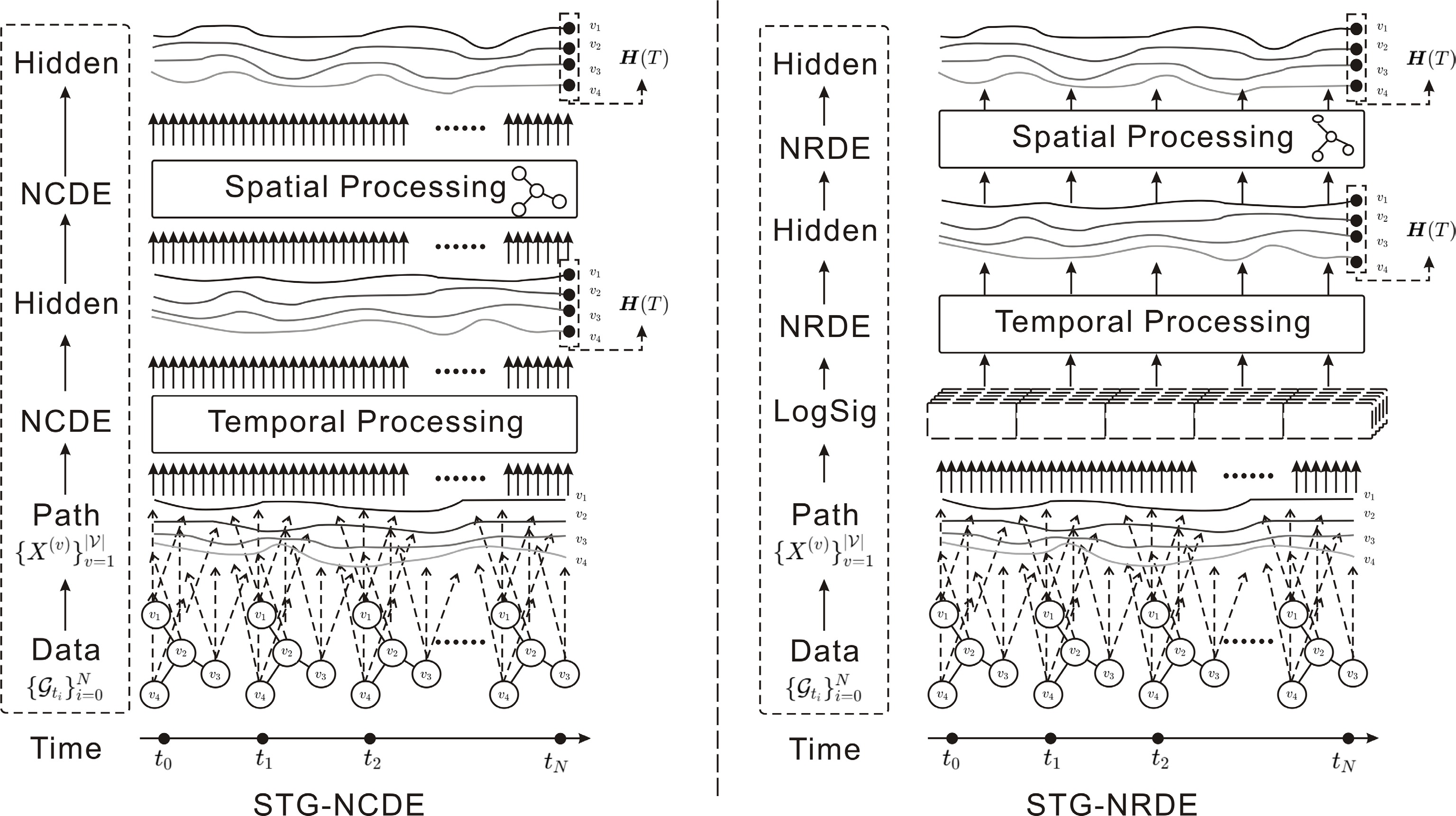

Differential equations offer a natural framework for representing traffic flow as a continuous function of both time and space. The combination of neural networks and differential equations has given rise to a new class of models that integrate the representational power of deep learning with the theoretical rigor of differential equation modeling. Often referred to as Neural Controlled Differential Equations (NCDEs) and Neural Rough Differential Equations (NRDEs), these models have achieved breakthroughs in sequential data modeling by treating sequential data as observations of continuous-time dynamics (Fig. 18).

Figure 18.

STG-NCDE and STG-NRDE: Temporal and spatial NCDEs/NRDEs jointly model continuous-time dynamics and intricate patterns in traffic flows.

STG-NCDE[64] integrates two distinct Neural Controlled Differential Equations (NCDEs) within a unified framework. One NCDE focuses on the temporal dimension, capturing the evolution of traffic patterns over time, while the other NCDE addresses the spatial dimension, modeling the complex interactions and dependencies among different locations in a road network.

STG-NRDE[65] utilizes Neural Rough Difference Equations (NRDEs) to process sequential data and extends the concept to temporal and spatial dimensions. The authors designed two NRDEs, one for each dimension, and integrated them into a cohesive framework to capture the complex dynamics of traffic flows. The key innovation of this work is its ability to handle irregular time-series data and model the intricate interdependencies in traffic data more effectively than traditional approaches.

-

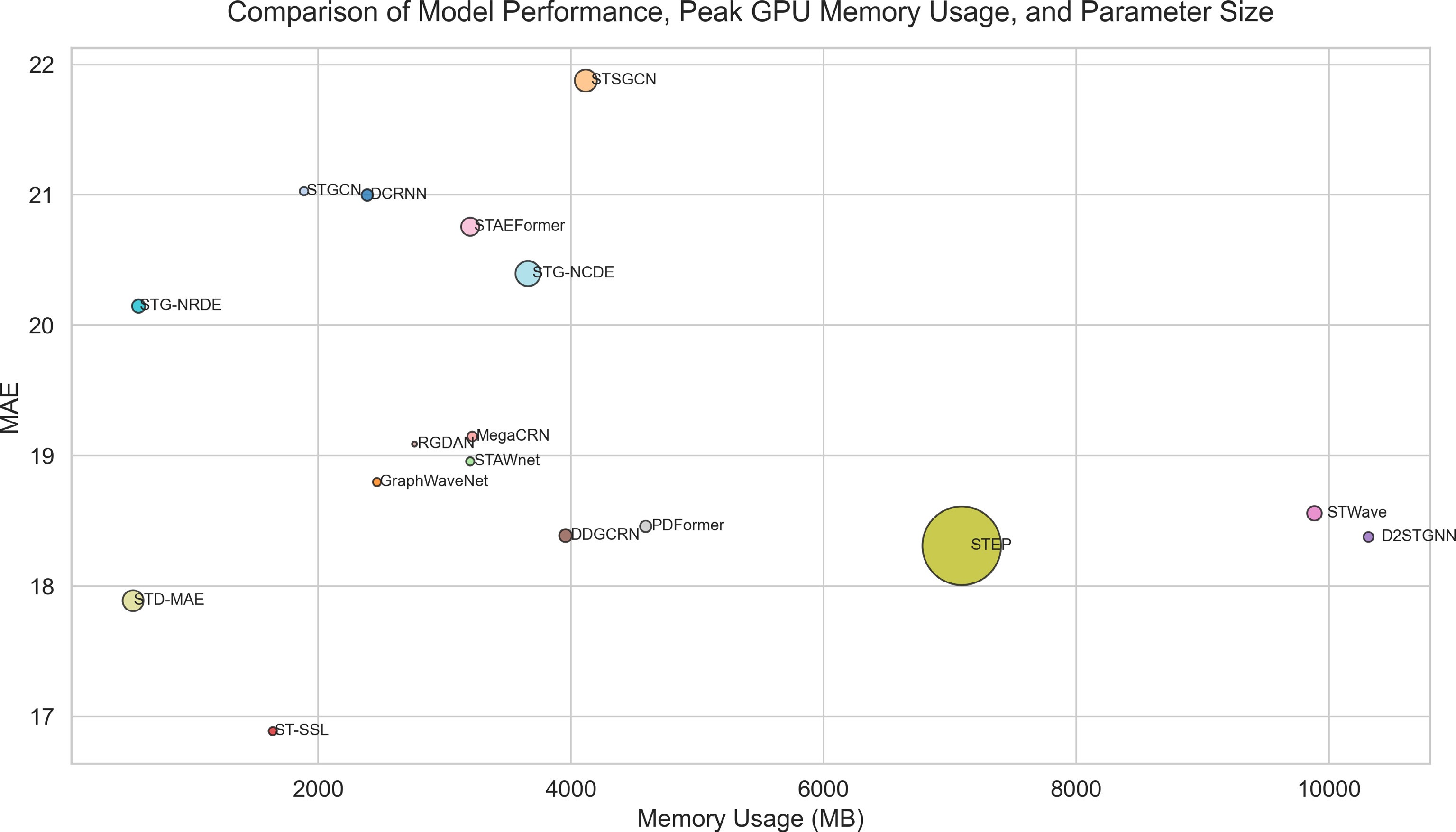

To establish a fair benchmarking protocol and provide practical guidance for model selection in real-world applications, a systematic evaluation was conducted on the PEMS04 dataset. Specifically, a diverse set of representative spatiotemporal forecasting models were re-implemented, including the following: DCRNN[49], STGCN[50], GraphWaveNet[51], STSGCN[52], STAWnet[53], ST-SSL[54], MegaCRN[55], D2STGNN[56], DDGCRN[57], RGDAN[58], STWave[59], STAEFormer[60], PDFormer[61], STEP[62], STD-MAE[63], STG-NCDE[64], and STG-NRDE[65]. The prediction task is formulated as forecasting the next 12 time steps using a 12-step lookback window, with each step corresponding to 5 min, so that 12 steps cover 1 h in the PEMS04 dataset.

To ensure methodological rigor and comparability, all models were trained and evaluated using the same hyperparameter settings as reported in the original papers. In addition, the computational environment was unified across all experiments (see Table 3) to minimize potential biases arising from hardware or software variations.

Table 3. Device information.

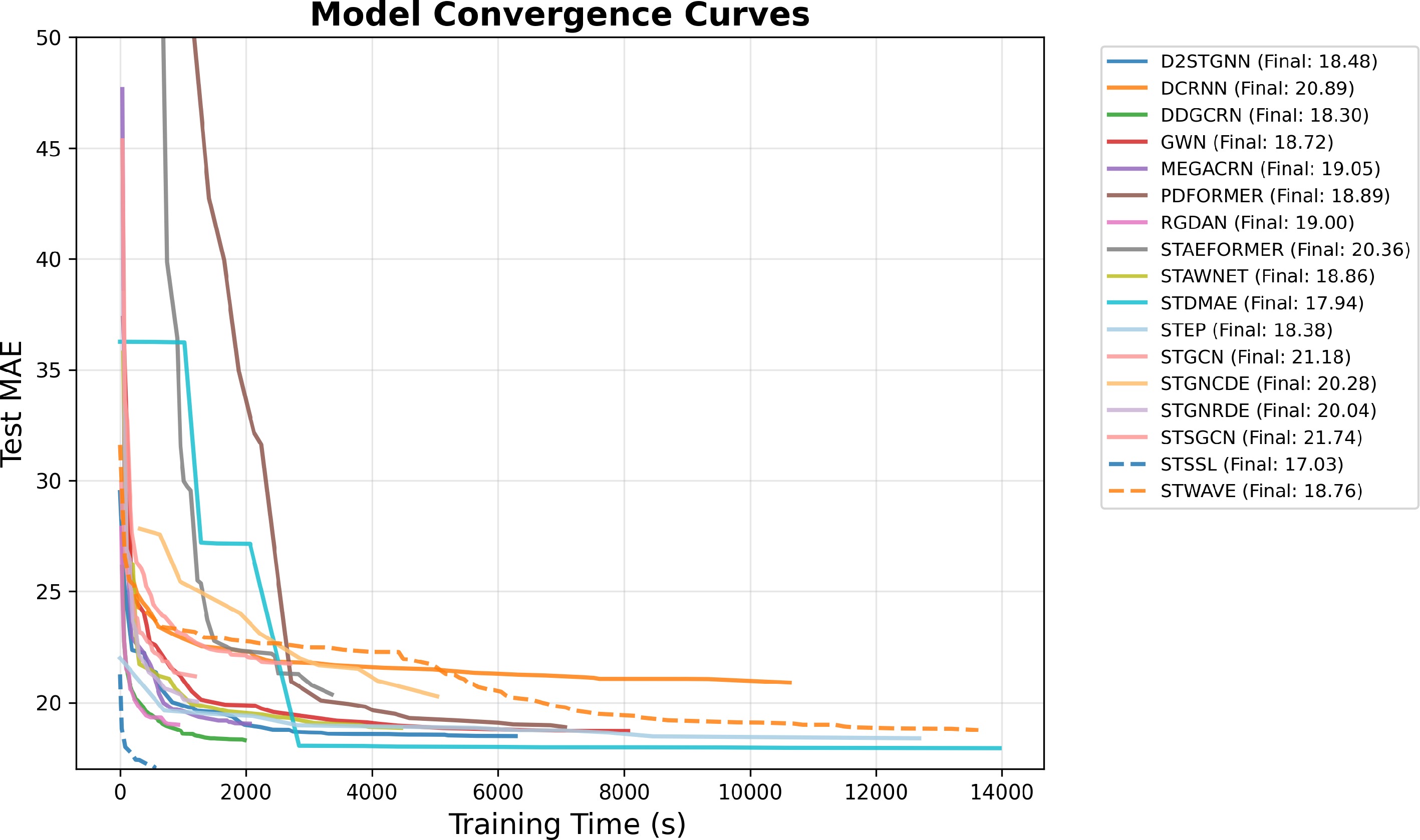

Device Info CPU Intel(R) Xeon(R) Gold 6133 CPU @ 2.50GHz GPU NVIDIA GeForce RTX 4090 RAM 32 GB VRAM 24 GB Python 3.10.16 CUDA 12.3 PyTorch 2.6.0 During benchmarking, various aspects of model performance were systematically tracked, including GPU memory footprint, CPU memory usage, parameter size, predictive accuracy, and runtime efficiency. Figure 19 provides an overview of each model's predictive performance, peak GPU memory usage, and parameter size, providing a clear reference for model selection in practical applications. Table 4 presents detailed runtime statistics for all evaluated models. Note that HA, ARIMA, and VAR are not deep learning models and do not involve a training process; therefore, some metrics, including GPU memory usage, are omitted.

Table 4. Runtime, resource usage, and predictive performance of models on PEMS04.

Model Params MAE RMSE MAPE VRAM RAM Iter per second HA − 38.03 59.24 27.88 − − − ARIMA − 33.73 48.80 24.18 − − − VAR − 24.54 38.61 17.24 − − − DCRNN 546,881 21.00 33.16 14.66 2,385.22 1,276.96 3.09 STGCN 297,228 21.03 33.38 15.07 1,886.88 1,177.90 14.30 GraphWaveNet 278,632 18.80 30.87 12.38 2,461.48 1,241.01 5.46 STSGCN 2,024,445 21.88 35.49 15.29 4,114.91 1,028.78 7.09 STAWnet 281,756 18.96 31.35 12.72 3,200.94 1,254.59 5.21 ST-SSL 288,275 16.89 26.98 10.48 3,208.00 1,566.00 16.19 MegaCRN 392,761 19.15 31.36 12.58 3,217.96 1,140.38 7.72 D2STGNN 398,788 18.38 30.10 12.06 10,310.0 5,067.00 6.34 DDGCRN 671,704 18.39 30.73 12.09 3,957.25 1,441.35 8.38 RGDAN 107,285 19.09 32.10 12.99 2,759.20 1,164.68 19.12 STWave 882,558 18.56 30.36 12.81 9,884.15 4,712.99 2.17 STAEFormer 1,354,932 20.76 32.38 20.06 3,200.36 1,217.37 19.88 PDFormer 531,165 18.46 29.97 12.67 4,591.52 5,351.85 1.64 STEP 25,469,726 18.31 29.90 12.49 7,091.23 1,936.99 2.02 STD-MAE 673,384 17.89 29.33 12.11 532.70 3,628.76 99.72 STG-NRDE 716,628 20.15 32.22 13.51 577.83 3,739.68 5.26 STG-NCDE 2,600,532 20.40 32.30 13.95 3,657.37 3,793.33 0.85 Figure 20 presents the relationship between training time and MAE, illustrating the model's convergence speed toward a target performance level. This curve provides insights into the model's training efficiency, indicating not only the total computational cost required to achieve a given accuracy but also its convergence rate relative to other models. Such analysis facilitates evaluation of both effectiveness and practical applicability in real-world scenarios where training time is often a critical factor.

-

Deep neural networks have driven the development of traffic flow prediction. However, there are still some challenges in this field. In this section, future directions and challenges are discussed.

Few-shot learning and transfer learning

-

Effective traffic flow prediction remains challenging under insufficient data conditions, especially in the early stages of building new roads or traffic networks. Some cities may lack sufficient sensing infrastructure, resulting in limited available data[83]. Even in cities with a sufficient number of sensors, the amount of usable data in practical deployments can be severely limited due to the presence of noisy or missing measurements. This issue is particularly pronounced when considering multiple nodes simultaneously over a continuous time interval, highlighting data scarcity as a critical challenge. For instance, a case study is conducted using the PEMS04 dataset and the GraphWaveNet model. The model is evaluated with varying proportions of the training set—10%, 30%, 50%, 70%, and 100%—while keeping the validation and test sets unchanged. All models are trained with identical hyperparameter settings. Table 5 presents the results of this experiment.

Table 5. Model performance under different training data proportions.

Training data proportion MAE RMSE MAPE 10% 19.66 31.77 13.08% 30% 20.12 32.54 13.15% 50% 19.87 31.97 13.64% 70% 19.50 31.54 12.66% 100% 18.82 30.78 12.41% Notably, it was observed that using only 10% of the training set outperforms models trained with 30%, 50%, or 70% of the data. This counterintuitive result may be attributed to sampling bias or noise distribution in the training subsets. Nonetheless, overall, model performance generally improves as the training data volume increases. This indicates that data quantity remains a critical factor affecting model effectiveness. Consequently, few-shot learning and transfer learning techniques have become key research focuses[84−86].

Few-shot learning and transfer learning are two effective approaches for addressing data scarcity[87]. Few-shot learning aims to achieve effective model training and generalization with very limited samples[88]. It improves the generalization ability of models with few samples through methods such as metric learning and data augmentation. Transfer learning enhances the performance of target domain models by transferring pre-trained models or knowledge from one domain (source domain) to another domain (target domain)[89]. It can effectively predict traffic conditions in newly built roads or regions with sparse traffic data using techniques such as model fine-tuning, feature transfer, and cross-domain adaptation.

In recent years, few-shot learning and transfer learning have shown preliminary progress in traffic flow forecasting tasks. Chen et al.[90] proposed a cross-city transfer learning framework that integrates multi-semantic fusion with hierarchical graph clustering, which enables the model to capture dynamic traffic states, preserve static spatial dependencies, and leverage multi-granular information via simultaneous multi-scale prediction. Ouyang et al.[91] proposed a graph-based domain adversarial framework for cross-city spatiotemporal prediction, leveraging self-adaptive spatiotemporal knowledge, a knowledge attention mechanism, and dual domain discriminators to extract domain-invariant features. Li et al.[92] proposed a physics-guided multi-source transfer learning method for multi-region traffic flow, which leverages prior knowledge from observations, empirical studies, and traffic network physical properties, and transfers network traffic features using adversarial training combined with an Macroscopic Fundamental Diagram (MFD)-based weighting scheme.

Future research in traffic prediction could further explore cross-city transfer learning and few-shot learning to address challenges posed by data scarcity in newly deployed sensors or regions. One promising direction is the development of dynamic multi-source transfer frameworks that leverage both static and evolving traffic network properties. These frameworks incorporate long-term, high-resolution data and real-time traffic regulation records. In parallel, advanced adaptation techniques are needed to mitigate issues such as overfitting and catastrophic forgetting, ensuring robust knowledge transfer across heterogeneous spatiotemporal domains, such as trajectories, weather, and points of interest. Combining these strategies may enable the development of more generalizable and adaptive models capable of few-shot learning in new cities or traffic scenarios.

Multimodal data in traffic flow prediction

-

Subtle changes in traffic flow often have a great impact on future traffic flow. Due to the inherent randomness of traffic flow and external noise, such as accidents, weather conditions, manual traffic control, or detector malfunctions, accurately identifying effective changes in traffic flow and filtering noise is challenging[93]. Multimodal data fusion is an effective approach that integrates multiple data sources and thus improves the accuracy of traffic flow prediction. By integrating multiple data sources, such as traffic surveillance videos, GPS trajectories, meteorological information, and social media data[94], researchers can build more comprehensive and robust traffic flow prediction models. These diverse data sources provide rich information that can help the model better understand the complex dynamics and potential patterns of traffic flow.

Multimodal data fusion techniques aim to extract features from different data sources and effectively combine these features to enhance the model's predictive capability. Multi-view learning and deep fusion strategies are two commonly used methods[95]. Multi-view learning captures the diversity of traffic flow by processing data from different views[96], while deep fusion strategies use deep learning models, such as convolutional neural networks and graph neural networks, to deeply integrate multimodal data[97], thereby making full use of the complementary advantages of different data sources and improving the accuracy and robustness of predictions.

Future research can further explore the application of multimodal data fusion in traffic flow prediction. This can improve model adaptability in diverse data environments and enhance the understanding of complex traffic scenarios by incorporating additional data sources. Meanwhile, as sensor technology and data collection methods continue to advance, multimodal data fusion is expected to be widely applied in real-world traffic scenarios, promoting the development of intelligent transportation systems and enabling more accurate and efficient traffic management.

Development of a lightweight and effective traffic flow prediction model

-

As the scale of the transportation network expands, a large amount of traffic flow data is being collected. These data provide a wealth of information for traffic flow prediction, but also impose higher demands on model computational capabilities[98]. Currently, models require substantial computational resources to process large-scale road network data[99], making the development of lightweight and effective models an important future research direction.

Future research can further explore the use of efficient graph neural network algorithms and parallel computing techniques in traffic flow prediction. Such approaches can enhance model processing capabilities for large-scale data while reducing computational costs through optimized resource utilization. With ongoing advancements in computing hardware and algorithms, lightweight and efficient models are expected to see broader application in real-world traffic scenarios, thereby supporting the development of intelligent transportation systems and enabling more accurate and efficient traffic management.

-

In this article, machine learning–based traffic flow prediction is reviewed. First, the background of traffic flow prediction tasks is introduced, and the problem definition of traffic flow prediction is provided. Three common traffic flow metrics and three standard measures of model predictive performance are summarized. Next, the 15 traffic flow datasets used in previous studies are reviewed, with detailed descriptions of how these datasets have been pre-processed.

The discussion begins with classical machine learning models and then explores more recent deep learning models. In particular, graph neural networks and spatiotemporal convolutional networks are discussed, including state-of-the-art pre-trained models and differential equation–based models. Finally, based on this review, three future research directions for traffic flow prediction are proposed. These directions include few-shot and transfer learning, multimodal data integration, and the development of lightweight and efficient models.

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 62462021), the Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Project of Zhejiang Province (Grant No. 25JCXK006YB), the Hainan Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 625RC716), the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant No. 2025A1515010197), the Hainan Province Higher Education Teaching Reform Project (Grant No. HNJG2024ZD-16), Hainan Postgraduate Innovation Research Project (Grant No. Qhys2023-127), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2021YFB2700600), and Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 2025JJA170089). The authors express their gratitude to the reviewers and editors for their valuable feedback and contributions to refining this manuscript.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: draft manuscript preparation: Zhang H; investigation: Lin Z, Zhou J, Sun J; supervision: Zhou T; project administration: Cao C. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Github repository https://github.com, and listed in the Supplementary Table S1; further details can be found in references [49–65] and [100−102].

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Data used in this study.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang H, Lin Z, Zhou J, Sun J, Zhou T, et al. 2025. A comprehensive review of traffic flow prediction: from traditional models to deep learning architectures. Digital Transportation and Safety 4(4): 281−297 doi: 10.48130/dts-0025-0027

A comprehensive review of traffic flow prediction: from traditional models to deep learning architectures

- Received: 11 May 2025

- Revised: 21 October 2025

- Accepted: 06 November 2025

- Published online: 31 December 2025

Abstract: Traffic congestion gradually becomes an increasingly serious problem in cities. Intelligent transportation systems (ITS) have been introduced to alleviate traffic congestion. Traffic flow prediction, as an important part of ITS, has become a research hotspot in recent years. This study presents machine learning techniques in traffic flow prediction. First, it systematically introduces the task of traffic flow prediction, including the research background and problem definition. Then, it reviews twelve benchmark datasets commonly used for traffic flow prediction and provides a detailed description of the data processing steps. After that, this study highlights the theoretical foundations and significant impact of Graph Convolutional Networks for traffic flow modeling. Finally, this study provides an in-depth analysis of the opportunities and challenges in this field and offers pertinent suggestions for future research. Overall, this study can help researchers quickly get started with traffic flow prediction.