-

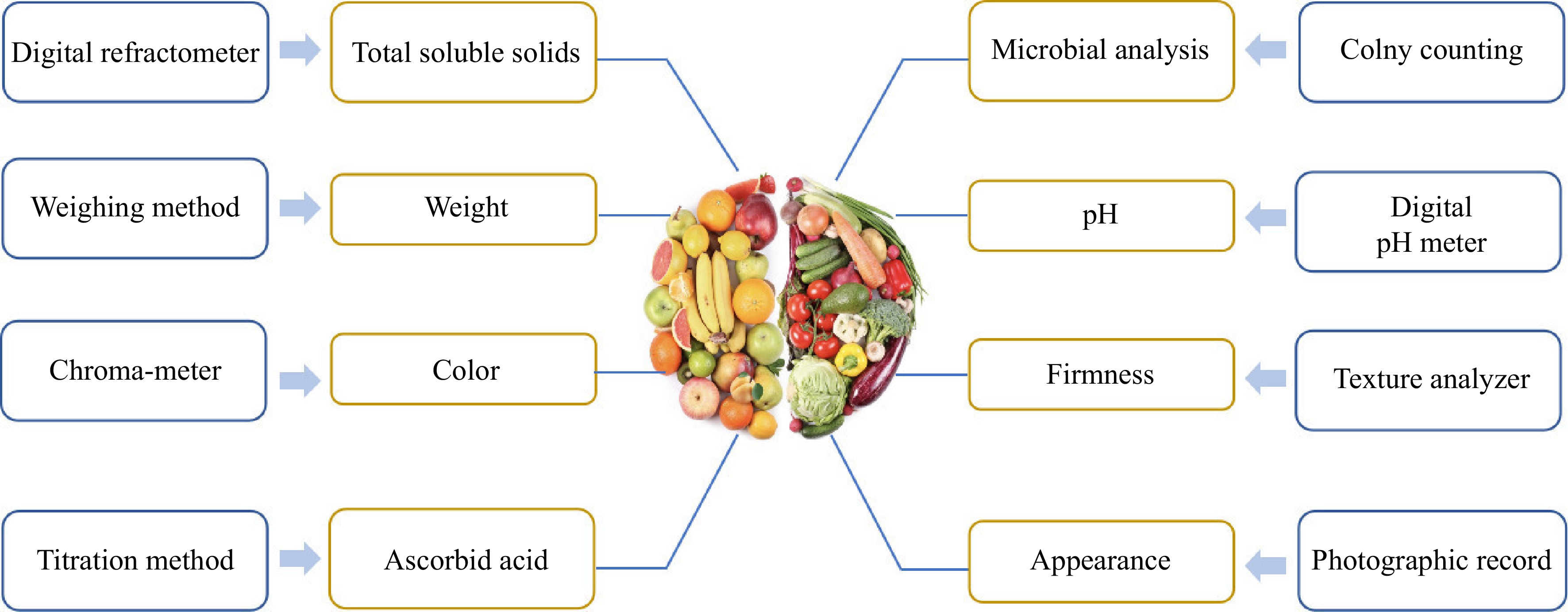

Fruits and vegetables are an indispensable part of the human diet. The FAO and the World Health Organization recommend that adults consume at least 400 g of fruits and vegetables per day. Adequate intake of fruits and vegetables can provide a variety of nutrients and phytochemicals that reduce the risk of heart disease, prevent cancer and other diseases, and maintain optimal health[1]. However, the physical damage and their own respiratory and other metabolic reactions could cause the growth of microorganisms on the surface of fruits and vegetables[2]. Food decay, microbial contamination, and moisture loss not only cause waste of food resources but also cause critical harm to human health[3]. In the supply chain, the loss or waste of fruits and vegetables is higher than that of other foods. According to the FAO, up to 50% of the fruits and vegetables produced in developing countries are lost along the supply chain between harvest and consumption. As shown in Fig. 1, many indicators can reflect the quality of fruits and vegetables, such as color, hardness, and total soluble solids content. Employing different methods allows for the effective detection of these indicators. The traditional preservation methods could preserve fruits and vegetables for a short time, but there is a decrease in nutritional value[4].

In recent years, innovative food packaging systems to keep the freshness of fruits and vegetables during transportation and to extend their shelf life have been greatly developed in the food industry[5]. Packaging serves as an effective barrier, safeguarding food from mechanical damage and separating it from moisture, dust, radiation, and microorganisms in the surrounding environment[6,7]. At present, the most used food packaging materials are synthetic plastic polymers such as nylon, polypropylene, high-density polyethylene, low-density polyethylene, and polyethylene glycol terephthalate[8]. These materials are cheap, versatile, and widely used in packaging, but their non-biodegradability and contamination risks make them environmentally harmful, highlighting the need for biodegradable, functional alternatives[9,10]. Edible films are thin layers made from natural, edible materials designed to wrap and protect fruits and vegetables, thereby extending shelf life[11]. Commonly used substrate materials include polysaccharides (chitosan, sodium alginate, cellulose, agar), proteins (casein, zein), and lipids[2,12,13]. Stable films can be formed through physical and chemical crosslinking interactions. Some films, upon absorbing water, can form crosslinked hydrogels with a 3D structure[14]. Edible films can enhance their preservation effectiveness by incorporating functional substances such as antioxidants and antimicrobial agents. These films effectively slow down the spoilage process of fruits and vegetables by reducing moisture loss, controlling gas exchange, and inhibiting microbial growth, thereby maintaining their freshness and nutritional value[15].

There are various methods for preparing edible films. One of the most basic techniques is solvent casting, which has gained widespread use due to its simplicity and ease of operation[16,17]. Extrusion methods, which involve heating natural materials, produce films that are tougher and more stable[18]. Additionally, novel spinning technology has emerged, enabling the production of films with a nanofiber structure[19]. These methods are suitable for different types of polymer materials and meet the preservation needs of fruits and vegetables.

Edible films used for the surface packaging of fruits and vegetables are expected to possess excellent properties to fully achieve their protective and preservative effects. However, biopolymers often suffer from drawbacks such as low thermal stability, poor mechanical properties, and brittleness[20]. Single-component films typically do not yield optimal results in practical applications. To enhance their performance, researchers have employed various strategies, such as incorporating nanoparticles (e.g., silver nanoparticles, zinc oxide nanoparticles) through nanotechnology to improve the films' antibacterial properties and mechanical strength[21,22]; adding natural antioxidants (e.g., vitamin C, tea polyphenols) to enhance the films' antioxidant capabilities[23,24]; or introducing crosslinking agents and plasticizers to improve the crosslinking degree and thus increase the durability and functionality of the films[25].

This review summarizes the progress of edible films in fruits and vegetables packaging. We outline various methods for producing edible films and provide a comparative analysis of their advantages and disadvantages. Additionally, we focus on several key performance attributes of edible films and outline some strategies for improving them. Therefore, this review aims to provide valuable insights into selecting appropriate film preparation methods and improving these films from different perspectives to achieve a highly functional edible film.

-

Edible films are typically made from natural or synthetic polymers, which can be directly applied to the surface of food or incorporated into packaging films. These films serve to preserve food freshness through their barrier properties or the functional characteristics of additives[2,26]. Currently, there are numerous materials available for the production of edible films, such as polysaccharides and proteins. Different materials possess varying physical properties, necessitating the selection of an appropriate fabrication method. The processing techniques employed also directly influence the mechanical strength, gas permeability, moisture barrier properties, and other functional characteristics of the film. Table 1 presents the fabrication method of edible film for fruits and vegetables preservation applications. Common film fabrication methods include solvent casting, extrusion, and the spinning method.

Table 1. Fabrication method of edible film for fruits and vegetables preservation applications.

Constituent substance Fabrication method Food system Ref. Cactus mucilage, gelatin, plasticizer (glycerol/sorbitol), probiotic Casting Fresh-cut apple [27] Sargassum pallidum polysaccharide nanoparticles, chitosan Casting Cherry [28] Corn/cassava starch, glycerol, eugenol, gelatin microspheres Casting Fresh-cut apple [29] Zein, sodium alginate, glycerol Casting Chili peppers [30] Guar gum, candelilla wax, glycerol Casting Strawberry [31] Aloe vera gel, chitosan Casting Fresh fig fruits [32] Levan, pullulan, chitosan, ε-polylysine Casting Strawberry [33] Chitosan, cellulose nanocrystals, beta-cyclodextrin Casting Cherry [21] Pomegranate peel extract, jackfruit seed starch Casting White grapes [34] Succinylated corn starch, glycerol Extrusion Mango [18] Starch, gelatin, natural waxes Extrusion / [35] Gelatin, native corn starch Extrusion with the casting Mango [36] Cassava starch, wheat, oat bran Extrusion / [37] Zanthoxylum bungeanum essential oil, polyvinyl alcohol, β-Cyclodextrin Electrospinning Strawberry and sweet cherry [38] Baicalinliposomes, alcohol-chitosan Electrospinning Mushrooms [39] Zein, gelatin-proanthocyanidins-zinc oxide nanoparticles Electrospinning Cherry [40] Pullulan, citric acid, thyme oil Rotary jet spinning Avocados [41] Thymol, 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin, chitosan, polycaprolactone Solution blow spinning Tomato [42] Pullulan, Water-in-oil emulsions Solution blow spinning Fresh-cut apple [43] Corn starch, gelatin, hawthorn berries extract 3D printing / [44] Gelatin, glycerol, Garcinia atroviridis extract 3D printing / [45] /, not provided. Solvent casting method

-

Solvent casting is a simple and commonly used wet processing method. It consists of three main stages: dissolution, casting, and drying[46]. The first stage involves selecting an appropriate solvent to dissolve the polymer, with water, alcohol, or other non-toxic organic solvents being the most commonly used. The polymer and solvent are thoroughly mixed through stirring. In the second stage, the homogenized solution is poured into a pre-designed mold to form a uniform film. Following a period of drying, the solvent evaporates, resulting in the formation of the polymer film within the mold[47].

The selection of solvent and drying conditions is the pivotal factor in the solvent casting process. It is essential to choose a solvent that ensures optimal solubility of the polymer matrix while minimizing its expansion rate[48]. Furthermore, variations in drying time and humidity can significantly influence the mechanical properties of the film, with the specific drying parameters being determined by the type of plasticizer incorporated in the solution[49].

One of the primary advantages of solvent casting lies in its simplicity, low equipment cost, and low processing temperature, which prevent damage to heat-sensitive materials. Additionally, the intimate contact between the polymer and solvent promotes the formation of a more homogeneous film. However, the method is limited to the production of sheet or tubular films, and more critically, the extended drying times and the complex control of environmental variables pose challenges for large-scale industrial applications[50].

Extrusion method

-

In the extrusion process, solvents are either not used or only minimally added, as the film formation is achieved through heating and melting. The main equipment used in this process is the extruder, which consists of a feed zone, a kneading zone, and a heated extrusion zone[51]. The polymer matrix is introduced into the extruder, and plasticizers may be added to enhance the flexibility of the film, with starch being a commonly used matrix. The mixture undergoes shearing and conveying in the kneading zone, and is eventually heated and melted, forming a film at the mold outlet[52].

The final properties of the film are influenced by several factors, including temperature, screw speed, feed moisture content, and feed rate, as well as mold temperature[53]. Screw speed affects the particle size and swelling rate of the material, while temperature also impacts the water vapor permeability of the film[54]. The continuous nature of the extrusion process reduces processing time, allows for better control of process parameters, improves production efficiency, and makes large-scale production more feasible. However, extrusion imposes limitations on the thermal stability and moisture content of the raw materials, and the design, operation, and maintenance of the equipment contribute to increased production costs[55].

Spinning method

-

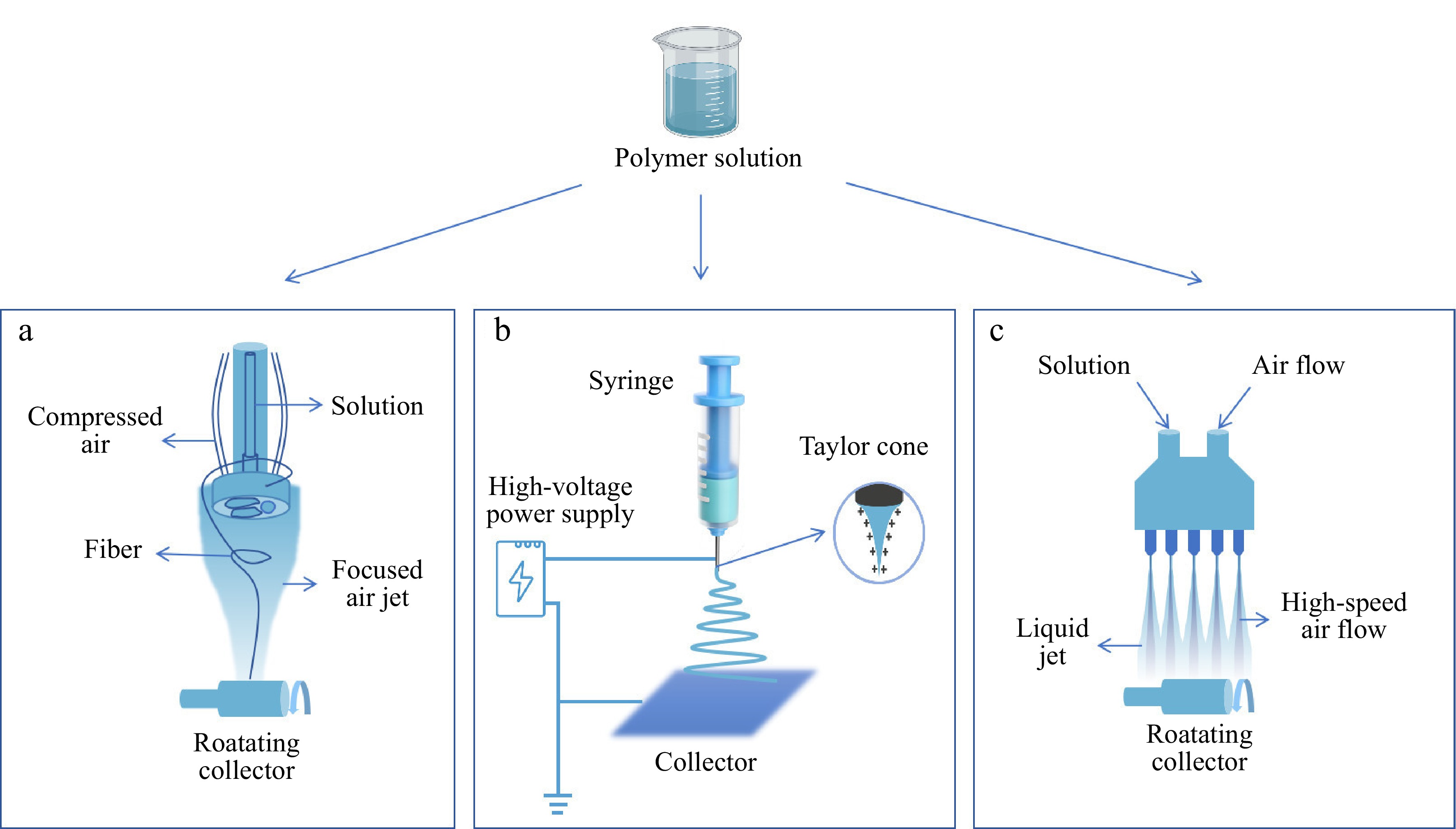

Spinning techniques applied in the field of materials include electrospinning, rotary jet spinning, and solution blow spinning, as shown in Fig. 2. Among them, electrospinning technology is the most widely used. Electrospinning, as an advanced non-mechanical fiber manufacturing technology[56], uses high voltage to produce nanofiber films. During electrospinning, due to surface tension, the liquid is forced out of the spinneret to produce pendant droplets. After electrification, the presence of electrostatic repulsion between surface charges of similar characteristics causes the droplet to undergo deformation into a Taylor cone, resulting in the ejection of a charged jet. Initially, the jet extends linearly until it starts to move vigorously due to bending instability. When the jet stream is stretched to a finer diameter, it rapidly solidifies, leading to the deposition of solid fibers on the grounded collector[57].

Figure 2.

Formation of different spinning film: (a) rotary jet spinning; (b) electrospinning; (c) solution blow spinning.

Rotating jet spinning technology is a manufacturing method that uses centrifugal force to induce dissolved polymer solutions to form fiber deposits on the target surface, and control the fiber pattern by a focused airstream[58]. The edible film containing natural antibacterial agents made by rotary jet spinning technology has been demonstrated to effectively control the growth of microorganisms on the surface of avocado and to maintain the weight of the fruit[41].

Solution blow spinning (SBS) is an emerging technology capable of rapidly producing nanofibrous films with high specific surface area and porosity from polymers[59]. The polymer solution is pulled into fine filaments under high-speed airflow, and upon solvent evaporation, a nanofiber film is formed on the collector[60]. In comparison to electrospinning, SBS does not necessitate a high-voltage power supply and exhibits significantly higher efficiency, which has led to its extensive utilization in the food packaging industry[42].

The fibers produced by spinning technology can reach the nanoscale and, by combining the properties of different polymers, can result in films with excellent physical and chemical properties. Additionally, it can address the issue of material functional degradation caused by heating[61]. As an emerging technology, spinning is not yet suitable for large-scale production due to its relatively low output and the complexity of the required equipment.

3D printing technology

-

In recent years, 3D printing technology has developed rapidly and has also been applied in the food industry. It is based on traditional additive manufacturing techniques, where edible materials are deposited or built layer by layer to form films with specific shapes and structures[62]. The process begins by mixing the base materials to create a film-forming gel, which is then stored in a syringe. When used, the gel is loaded into the printer's nozzle. The 3D printer can then print according to a set program, adjusting speed and temperature as needed[38,39].

Although 3D printing has shown potential in food packaging, it has not yet been widely explored. While it allows for the customization of films with specific textures and nutritional components, challenges remain. These include limitations in available printing materials, slow printing speeds, and high costs, all of which are hindered by underdeveloped processing technologies[62].

-

Mechanical properties are the most fundamental yet crucial characteristics of edible films. Films need to possess appropriate strength and ductility to withstand the stresses encountered during transportation, storage, and processing, thereby providing protective functions for the food. The mechanical properties of films include tensile strength, elongation at break, elastic modulus, puncture force, and puncture deformation[63]. Films with higher strength and toughness offer better protection, while adequate ductility ensures the film remains intact during handling.

Some polymeric materials exhibit hydrophilicity and poor mechanical performance, which results in suboptimal mechanical properties for single-component films, such as agar and chitosan[64,65]. However, interactions between different matrices can improve film performance through intermolecular forces. Thus, composite films made from two or more polymers have a higher potential for practical applications. Proteins and polysaccharides can enhance the tensile strength and elongation at break of films through intra- or intermolecular hydrogen bonding[66,67]. Polysaccharides can also form denser cross-linked structures, enhancing the overall network[68]. Although lipids are difficult to form into films on their own due to their structural characteristics, as an additive, lipids can significantly improve the rigidity and ductility of protein-based and polysaccharide-based films[69].

Plasticizers reduce the intermolecular forces between polymer chains, increasing chain mobility, thereby improving the flexibility and ductility of films. Common plasticizers include glycerol, propylene glycol, and sorbitol. Crosslinking agents (such as glutaraldehyde) can strengthen the 3D network structure of the film, thereby increasing its strength and hardness[25,70]. Research by Para et al. has shown that adding glycerol and polyethylene glycol as plasticizers, along with glutaraldehyde as a crosslinking agent, significantly affects the elongation at the break of films, while increasing glutaraldehyde content results in higher tensile strength[71].

The mechanical properties of the films were significantly affected by the addition of nanoparticles. With their high surface area and excellent interface compatibility, nanoparticles can form nanoscale strong connections within the film matrix, thereby enhancing its strength and rigidity. For instance, after the addition of 2.0 wt% copper sulfide nanoparticles (CuS NP), the thickness of the agar film increased from 51.8 to 60.2 μm, and the tensile strength improved from 34.9 to 41.1 MPa. These improvements arise from the increased solid content due to the presence of CuS NP, as well as the strong intermolecular interactions between the agar and CuS NP[72]. The tensile strength was significantly improved to ~60 MPa by adding zinc sulfide nanoparticles, while elongation at break and elastic modulus slightly increased and decreased. This may be attributed to the favorable interface interaction between the carrageenan/agar matrices and the nanofillers[73].

The processing method also impacts the mechanical properties of films. Longer drying times can promote crosslinking and crystallization of the film material, enhancing its mechanical properties. Appropriate heat treatment can also reduce the moisture content of the film. For example, starch forms a more compact 3D structure under prolonged drying conditions. This results in starch-based films produced via casting having higher tensile strength, lower elongation at break, and higher Young's modulus compared to those produced by hot pressing[74,75].

Barrier properties

-

The barrier properties of packaging films help prevent the loss of moisture in fresh fruits and vegetables, slow down oxidation and spoilage, and play a crucial role in maintaining their quality. Key indicators such as water vapor permeability (WVP) and water content (WC) can be used to characterize the films' barrier properties. Testing methods for these properties include manual techniques like pressure and gravity measurements, as well as automated methods such as gas permeability sensors and water vapor transmission sensors[76].

Edible films based on proteins exhibit good gas barrier properties but perform poorly in terms of water vapor permeability[77]. Although the properties of lipids are closely related to the length and unsaturation of fatty acid chains, their inherent hydrophobicity still leads to a strong hindrance to water migration in lipid-based films[13]. Polysaccharide-based films, on the other hand, have good hydrogen bonding between their structural components, which effectively prevents the permeation of oxygen and noble gases, but they show poor water resistance[78]. The barrier properties of films can be significantly altered by varying the polymer composition and ratio. The same effect can also be achieved by adding plasticizers and other substances. Table 2 summarizes the effects of different additives on the barrier properties of edible films. It is all achieved by altering the microscopic structure of the films.

Table 2. Effects of different additives on the barrier properties of edible films.

Additives Concentration Water content Water vapor permeability Water solubility Ref. Pectin 5% 30.79%−21.07% 13.39−29.25 × 10−3 g·m/h·pa 76.77%−83.32% [79] Whey protein isolate / 40.21%−21.85% 15.28−23.32 g/m2·day 34.71%−36.46% [80] Cellulose nanocrystals 75% 9.6236%−12.9845% 1.75−2.34 × 10−9 g/s·Pa·m / [81] Oxidized poly- (2-hydroxyethyl acrylate) 10% 17.01%−25.7% / 41.7%−56.9% [82] Tangerine oil, tween 80 0.10% 26.05%−20.25% 0.613−0.233 g·mm/m2·h·kPa 50.19%−45.94% [83] Arrowroot powder, refined wheat flour, corn starch 3.5%, 2%, 2% 13.69%−6.76% 0.0019−0.0106 g·mm/m2·day·mmHg 33.33%−24.35% [84] Black pepper essential oil 0.15% 31.79%−39.25% 0.315−0.420 g·mm/m2·h·kPa 24.00%−22.35% [85] Modified potato starch, glycerol 9%, 1% / 18.1−6.1 × 10−3 g·mm/h·m2·Pa 62.238%−45.639% [86] Sunnhemp protein isolate, potato starch 50%, 50% 18.31%−12.89% / 74.26%−52.77% [16] Orange oil 2.50% 16.12%−9.55% 2.71−2.25 × 10−12 g·cm/cm2·s·Pa 74%−29% [87] /, not provided. As the proportion of pectin in pectin-chitosan composite films increases, the films' porosity gradually increases, allowing more gases and moisture to pass through the matrix[88]. The addition of curcumin with a rod-like crystal structure to zein and shellac composite films hinders the penetration of water droplets on the film surface, thereby reducing the water contact angle of the film[89]. Conversely, adding plasticizers such as glycerol or sorbitol increases the water vapor permeability of the films. On one hand, this is due to the hydrophilicity of these substances; on the other hand, it is because the plasticizer reduces the density of the polymer's 3D network, thereby decreasing the difficulty of water permeation[90].

Environmental conditions also affect barrier properties in a manner similar to the principles outlined above. For example, Wu et al. prepared gelatin-dextran blend films with different microstructures, and compatibilities by adjusting the gelatin/dextran ratio and pH. The results showed that for films with the same composition, water solubility, and water vapor permeability increased as the pH value rose. This was attributed to macroscopic phase separation between gelatin and dextran, which disrupted the continuity and tightness of the network structure and facilitated water molecule transport[91]. Kerch & Korkhov found that, at room temperature, the water vapor absorption of chitosan films decreased as storage time increased. However, at −24 °C, the absorption showed the opposite trend, likely due to low temperatures causing the polymers' molecular conformation to expand, allowing water molecules to penetrate the polymer structure[92].

Thermal properties

-

Thermal properties directly influence the stability, operability, and performance of films under different storage conditions. Good thermal stability ensures that the film will not decompose or fail during cooling or heating processes, thus maintaining its protective properties. The most common methods for evaluating thermal properties include differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) to measure glass transition temperature, melting temperature, degradation temperature, and thermogravimetric analysis[93,94]. DSC helps assess the mechanical properties, stability, and processing performance of the film at high temperatures, while thermogravimetric analysis is used to analyze the thermal degradation of materials[95]. Additionally, some studies employ photoacoustic techniques to examine thermal diffusivity and thermal runaway, and calculate the thermal conductivity to characterize the heat transfer capability of the film[96].

Enhancing the crosslinking interactions between different film components can improve thermal stability. Research by Mojo-Quisani et al. showed that the addition of modified starch increased the compatibility with Nostoc, resulting in a more stable structure and reducing the maximum weight loss of the film during heating[86]. Similarly, Nedim pointed out that as the amounts of pineapple peel extract and aloe vera gel increased, the interactions formed between these substances and the polymer matrix required higher dissociation energy, thereby demonstrating improved thermal stability[97]. By forming a multi-crosslinked network with calcium ions, the relative sliding between agar molecular chains was hindered, raising the films' maximum degradation temperature from 243.5 to 301.7 °C[98].

New studies have also suggested that gamma-ray irradiation can narrow the N-H and O-H bonds, enhancing the molecular interactions between chitosan and glycerol. This result is an increase in the peak melting temperature of the chitosan-glycerol composite film from 173.4 to 190.2 °C[99]. This method of altering intermolecular interactions through radiation provides a novel approach to enhancing the thermal properties of films.

Optical properties

-

The transparency, color, and ultraviolet (UV) light barrier properties of films are the key optical characteristics. Generally, high transparency and suitable color can provide consumers with a pleasant visual experience, thereby increasing consumer acceptance[100,101]. On the other hand, higher UV light barrier properties can effectively protect food from UV damage, especially for light-sensitive substances, preventing oxidation and discoloration[102,103]. A colorimeter can be used to measure lightness ('L') and chromaticity parameters ('a' for red-green and 'b' for yellow-blue), while a UV spectrophotometer can analyze the transparency and UV blocking ability[104].

Film thickness significantly affects transparency. As the thickness increases, light scattering becomes more pronounced, resulting in lower transparency[105]. Similarly, the concentration of the polymer matrix influences film transparency in the same way, as increased aggregation of materials enhances light scattering[106]. While higher transparency allows for better food visibility, films with lower transparency exhibit stronger light-blocking properties[107]. These properties can be adjusted based on specific applications. The color parameters of the film largely depend on the composition of the material. For example, the addition of silver nanoparticles can turn the film yellow, and at higher concentrations, it appears brown[108]. The addition of plasticizers can dilute the polymer concentration, reducing overall color differences[109].

Some matrix materials inherently possess good UV-blocking capabilities. Purohit et al. have shown that pure chitosan films can block nearly 100% of UV-B and about 97% of UV-A radiation. The addition of cerium nanoparticle (CeNP) fillers enhances this UV-blocking property of chitosan films[104]. Certain active substances also possess natural UV-blocking abilities. Phenolic compounds, which contain unsaturated double bonds conjugated with saturated covalent bonds, can absorb UV and visible light[110]. The addition of a Pulicaria jaubertii extract, which contains phenolic compounds, significantly improved the films' barrier properties against UV and visible light[93]. Lignin also exhibits spectral blocking properties against UV radiation, likely due to functional groups in lignin (including phenolic, ketone, and other pigment groups) that absorb UV light. This suggests that incorporating natural active substances can enhance the UV-blocking ability of films[107].

Antibacterial and antioxidant properties

-

During the storage, transportation, and sale of fruits and vegetables, they are highly susceptible to microbial contamination, leading to issues with edibility and safety. Oxidation reactions can cause the degradation of nutrients such as fatty acids and vitamins, resulting in off-flavors, discoloration, and even the formation of toxic substances[26,111,112]. The addition of antimicrobial agents and antioxidants to the packaging films is the most direct and effective method for enhancing these properties.

Antibacterial agents are important functional components in fruits packaging films. But some novel antibacterial agents with safe, non-toxic, and broad-spectrum antibacterial activity properties will encounter some problems in application. For example, ε-polylysine will bind to anions in the food substrate to produce precipitation or bitterness due to its electrostatic properties[113]. The glass transition temperature of the polymer from 2-hydroxy-3-cardanylpropyl methacrylate is about −13.5 °C so the polymer film is sticky[114]. Therefore, it is important to find a delivery system that can balance high antimicrobial properties with good aggregation stability. Nanospheres made of functional components by cross-linking techniques can sustain-release polyphenols and protect them from deactivation[115]. Chen et al. prepared eugenol/gelatin microspheres by the emulsify-crosslinking method as shown in Fig. 3, and coated fresh-cut apple cubes with composite films containing eugenol/gelatin microspheres. The results demonstrated that the apple cubes exhibited no bacterial contamination, with only mild dehydration[29]. Liang et al. employed chitosan/silver nanoparticle composite microspheres for cherry preservation and observed remarkable efficacy in reducing decay rate and weight loss[116]. Yang et al. found that cinnamaldehyde-loaded polyhydroxyalkanoate/chitosan porous microspheres can reduce the rate of hardness loss of strawberries and keep the total soluble solids, titratable acidity, and ascorbic acid content stable[117]. These results show that the nanospheres have antibacterial and antioxidant properties that can extend the shelf life of fruits.

Essential oils (EOs) are volatile and fragrant liquids that are derived from plants, which have powerful antimicrobial activity[118]. Adding essential oils to food packaging can control food spoilage and foodborne pathogenic bacteria. However, in general, essential oils are composed of non-polar components, so they have poor water solubility, strong sensory flavor, and low stability[119,120]. Nanoemulsions are emulsions with nanoscale droplets, typically formed by dispersing two or more immiscible liquids (such as oil and water) into tiny particles through physical methods like high-pressure homogenization, microfluidization, and ultrasonication[121]. The particle size of nanoemulsions generally ranges from 20 to 200 nm, which is significantly smaller than that of conventional emulsions[122]. This smaller particle size imparts nanoemulsions with higher stability, a larger surface area, and enhanced penetration capabilities[123]. Nanoemulsion technology aims to shield essential oils from the influences of environmental conditions, diminish their toxicity, conceal their potent flavor and aroma, and enhance their bioavailability[124]. Compared to traditional emulsions, nanoemulsions containing functional ingredients offer advantages such as smaller diameters, higher transparency, increased stability, and improved antimicrobial activity[125]. Liu et al. stabilized the nanoemulsion with carboxymethyl chitosan-peptide conjugates and prepared an active film containing camellia oil. Experimental results showed that it could maintain the firmness, reduce weight loss, and slow down the formation of soluble solids in blueberry[126]. Malondialdehyde (MDA) is a marker of membrane peroxidation and its content can be used to measure membrane integrity[127]. Sodium alginate/tea tree essential oil nanoemulsion active film-coated fruits have the lowest MDA content compared with uncoated groups by the end of storage, which means the suppressive effect on lipid peroxidation[128].

-

This review discusses the methods and properties of edible films for fruits and vegetables. Solvent casting is a commonly used wet-processing technique, where the key factors are selecting the appropriate solvent and controlling the drying conditions, both of which affect the films' properties. The extrusion method, which involves heating and melting the polymer with minimal solvent use, is more suitable for large-scale production. While the process parameters influence the films' properties, this method requires high-quality raw materials and has higher equipment maintenance costs. Spinning can produce nanoscale fibers, but its low output and complex equipment have limited its widespread application. The development of 3D printing in the food sector has been slow, constrained by limitations in materials and technology, along with high costs, and slow speeds. However, it holds potential for future development. The mechanical properties of edible films determine their protective performance during transportation, storage, and processing. Combining different polymers can enhance the films' strength and flexibility. Plasticizers like glycerol and crosslinking agents such as glutaraldehyde improve the films' flexibility and strength. Nanoparticles and processing methods like drying and thermal treatments can also boost the films' mechanical properties. Barrier properties, including water vapor and oxygen permeability, are essential for food protection, and the choice of polymers and plasticizers affects these characteristics. Thermal properties, transparency, color, and UV-blocking ability also influence the films' stability and appearance. Furthermore, certain natural substances and antioxidants can enhance the films' functionality.

The future of edible film technology is not limited to the food industry; and it has the potential to extend into fields such as medicine and agriculture, offering a wide range of applications. Furthermore, there is a need for further advancements in the application technology of edible films and coatings to meet consumer demands for both functionality and visual appeal. In addition to antibacterial and preservation properties, functionality can be expanded to enhance the nutritional value of food by incorporating probiotics and other methods. Moreover, with the rapid development of internet technology, edible films, and coatings can be integrated with technologies like the Internet of Things, big data, and artificial intelligence to create intelligent packaging systems, thereby ensuring the freshness and safety of food more effectively.

This research was supported by the Zhejiang University-Wencheng Health Industry Joint Research Center Project (Zdwc2307).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: writing - original draft: Pan JN; writing - revision: Sun J, Shen QJ, Zheng X, Zhou WW; language editing: Zheng X; supervision and project administration: Zhou WW. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

-

Authors contributed equally: Jia-Neng Pan, Jinyue Sun

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Pan JN, Sun J, Shen QJ, Zheng X, Zhou WW. 2025. Fabrication, properties, and improvement strategies of edible films for fruits and vegetables preservation: a comprehensive review. Food Innovation and Advances 4(1): 43−52 doi: 10.48130/fia-0025-0003

Fabrication, properties, and improvement strategies of edible films for fruits and vegetables preservation: a comprehensive review

- Received: 26 July 2024

- Revised: 28 November 2024

- Accepted: 30 December 2024

- Published online: 24 January 2025

Abstract: In the process of post-harvest storage and transportation, the quality of fresh fruits and vegetables are decreased due to the autogenetic physiological effect and microbial pollution, which causes great losses to the food industry. Food packaging using edible film and coatings is an emerging environmentally friendly method of fruits and vegetable preservation. This review provides an overview of various film fabrication techniques, including solution casting, extrusion, electrospinning, and 3D printing, while examining the advantages and limitations of each method. A detailed analysis is offered on the key performance parameters of these films, such as mechanical strength, water vapor permeability, antioxidant activity, antimicrobial properties, and their effectiveness in preserving fruits and vegetables. Additionally, strategies to enhance the performance of edible films through incorporating nanoparticles, natural additives, and crosslinking methods are explored. The review aims to establish a comprehensive theoretical foundation and offer practical insights to support the further development and application of edible film technology in fruits and vegetables preservation.

-

Key words:

- Edible film /

- Fabrication methods /

- Food packaging /

- Fruits and vegetables /

- Property