-

Medicinal plants serve as the primary reservoirs of numerous essential natural compounds, playing a crucial role in human health through disease prevention and treatment. Prominent examples, such as artemisinin from Artemisia annua, tanshinone from Salvia miltiorrhiza, and ginsenosides from Panax ginseng, contribute significantly to human well-being[1]. The importance of these botanical resources has been further accentuated in the aftermath of the recent COVID-19 pandemic, highlighting the increasing reliance of humanity on these botanical resources[2]. However, like all plant species, medicinal plants encounter diverse environmental stresses during their growth. Particularly, extreme environmental stresses such as drought, flooding and heat stress, resulting from the global climate changes, pose huge challenges to plant growth[3,4]. These abiotic stresses increase the uncertainty in the yield and quality of medicinal plants, profoundly impacting downstream industrial production and human health. Thus, it is imperative to enhance the resilience of medicinal plant to environmental fluctuations.

Plants have evolved multiple strategies to cope with these challenges, which have been widely documented at the physiological and molecular levels. For instance, plants adapt to drought conditions by elongating roots, developing lateral roots, and enhancing the expression of aquaporins in order to facilitate water resource utilization[5]. Under salt-induced osmotic stress, plants employ physiological mechanisms such as actively secreting salt through salt glands[6] or passively excluding Na+ from entering cells through the plasma membrane[7] to enhance adaptability. To counter heavy-metal stresses, plants can activate reactive oxygen species-mediated antioxidant systems or regulate the expression of stress-related transcription factors, such as bZIPs, MYBs, AP2, and DREN2B, through miRNA modulation[8,9]. Beyond these intrinsic strategies, plant-associated microorganisms, acting as the second genome of plants (if the organellar genomes of plants are not considered as separate entities), also play a crucial role in plant growth, development, and adaptation to environmental stresses. For instance, Li et al.[10] showed that the salt-recruited beneficial soil bacteria could effectively enhance plant adaptability to salt stress. This theory also applies to the endophytic microorganisms, as endophytic bacterial incubation has been demonstrated to not only enhance plant tolerance to abiotic stresses, but also increase the accumulation of secondary metabolites[11,12]. Moreover, the link between microbial communities and plant nutrient uptake, yield formation, and stress adaptation is well-established[13,14]. However, to date, the significance and functional mechanisms of these microorganisms in modulating adverse environmental fluctuations within medicinal plants remain to be fully elucidated.

Here, we systematically survey the responses of plant-associated microorganisms, encompassing both rhizospheric and endophytic communities, to common abiotic stresses experienced by plants, and review the crucial role of these organisms in facilitating plant adaptation and promoting the synthesis of medicinal compounds. The present study aims to provide essential insights for future cultivation of medicinal plants in the face of climate change scenarios.

-

Abiotic stresses such as drought, salinity, and heavy metals have been demonstrated to affect both plant growth and development, as well as the associated rhizospheric or endophytic microbial communities, owing to their intricate interplay[15]. Such influence arises partly from the direct environmental effects, such as alterations in soil moisture and salinity, which subsequently affect the diversity and composition of soil microorganisms[16]. Equally importantly, plant physiological and metabolic responses to stresses indirectly shape the assembly of these microbial communities, particularly via the secretion of key compounds into the rhizosphere zone by root system[17]. Indeed, numerous studies have reported the microbial responses to abiotic stresses, with most studies revealing predominantly negative or insignificant impacts. For instance, via meta-analysis, Quiroga et al.[18] demonstrated that drought stress significantly decreased the abundance of rhizosphere microorganisms, particularly fungi, without significantly affecting phyllosphere microorganisms. Similarly, Signorini et al.[19] showed that copper (Cu), instead of cadmium (Cd), negatively affects the α-diversity of rhizosphere bacteria in a dose-dependent manner. These adverse effects underscore the sensitivity of microbial communities to environmental perturbations. In the context of medicinal plants, understanding these interactions is particularly crucial given their unique natural habitats and the specific metabolic compounds which they produce.

The diversity and patterns of assembly of microbial communities are key indicators of ecosystem function and biotic interactions, which are intimately connected to the fluctuations within the environment. In the case of the rhizosphere microbiome, limited research indicates a potentially pronounced negative effect of drought stress on the rhizobacterial diversity of medicinal plant rhizospheres, but a potential benefit to fungal communities[20,21]. Comparable results have been observed under heavy-metal stress, with a study on Tamarix ramosissima revealing that bacterial diversity was more negatively affected by heavy metal stress than fungal diversity[22]. Such an influence of salt stress is more complex, as both positive[23], negative[24], and negligible effects[25] have been documented. This variability is likely attributable to differences in the salt tolerance among plant species and the specific conditions of stress exposure, such as duration and intensity. Additionally, soil nutrients are speculated to be a key factor in shaping rhizosphere microbiome assembly. For example, Su et al. found that variations in nutrients such as potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), copper (Cu), and iron in the core planting area of citrus determine rhizosphere microorganism compositions, which in turn influence the synthesis of citrus terpenes[26]. Similarly, research on Glehnia littoralis demonstrates that varied soil nutrients act as key influencers at various developmental stages, with pH and available phosphorus (P) positively impacting bacterial and fungal communities during early development stages, while nitrate enhances these communities in the middle and late growth stages[27]. Interestingly, N deficiency may enhance the bacterial diversity, as seen in Lycium barbarum[28]. While studies on the relationship between other soil nutrients and the assembly of rhizosphere or endophytic microbial communities in medicinal plants are limited, it is hypothesized that P deficiency might reduce bacterial diversity but increase fungal diversity. This could strengthen the role of deterministic processes in shaping bacterial community assembly, as suggested by research in rice plants[29]. Additionally, a study on ginseng has identified soil total K as a key driver of the temporal dynamics of core-enriched bacterial communities in bulk and rhizosphere soils[30]. Thus, further research is needed to fully understand the impact of P or K deficiency on rhizosphere microbial communities in medicinal plants.

Notably, these stresses would also reshape the composition and structure of rhizosphere microbial communities, while the responses may vary according to plant type and stress intensity. For instance, an examination of Atractylodes lancea has demonstrated that severe drought stress decreases the relative abundance of Proteobacteria phylum, whereas moderate stress leads to an increase of species of this phylum[21]. In the case of Stevia rebaudiana experiencing moderate drought stress, bacteria belonging to the phyla of Actinobacteria, δ-Proteobacteria, Planctomycetes, and Chloroflexi were mainly enriched[31]. The enrichment of these microbes are partly associated with functions related to carbohydrate metabolism, lipid and secondary metabolite metabolism, which may be helpful in osmotic stress regulation since all of these compounds have been documented to play such a function[32−34]. Under salt stress, specific microbes like those from the orders Micrococcales and Bacillales have been observed to be enriched in some studies while others suggest no significant shifts in the dominant bacterial phyla[23,35]. These examples suggest that the selective enrichment of microbes under stresses is substantially influenced by the host, which can attract and recruit beneficial bacteria via releasing specific root exudates. Notably, root exudates, comprising a diverse array of compounds such as carbohydrates, organic acids, amino acids, and secondary metabolites, are well-documented to be capable of enhancing plant tolerance to abiotic stress by attracting specific beneficial microorganisms within the rhizosphere acting as chemical signals[36,37]. As evidence in support of this, Pan et al.[38] demonstrated that the assembly of rhizosphere bacteria under drought and salt stress is accompanied by the accumulation of rhizosphere compounds such as organic acids, growth hormones, and sugars. Additionally, a study on Limonium sinense indicated that plants can attract and recruit beneficial bacteria through organic acids secreted from roots, promoting plant growth under salt stress[39]. This selective enrichment is further exemplified under low-N stress, where the secretion of C-containing compounds from roots may alter the C-N ratio in rhizosphere soil, thus recruiting specific rhizosphere bacteria to improve N use efficiency. This can lead to an increase in the relative abundance of Acidobacteriota and Myxococcota phyla, as well as ammonia-oxidizing bacteria such as Nitrosospira[28,40]. In addition, theanine secreted by tea plants has been shown to significantly changed the structure of the rhizosphere microbiota, selectively shaping rhizosphere microbial assembly[41].

Alterations in the network structure of rhizosphere microorganisms when subjected to stress conditions are equally importance, reflecting the complex interactions among microbial species and the ecological stability of the community. For example, studies on the assembly of rhizosphere bacterial communities in Stevia rebaudiana under drought stress have revealed simplified and unstable networks, yet also highlighted an increase in positive interactions and a strengthened deterministic assembly process[42]. Similar findings have been documented in salt-stressed Cynomorium songaricum[43], which further suggests that plants may be employing adaptive strategies to enhance their resilience to stresses. Additionally, N stress could reduce the number of edges in microbial occurrence networks, thereby altering network complexity and potentially increasing the contribution of deterministic processes to community assembly[40,42]. These changes in network complexity provide insights into microbial community adaptation and response to environmental pressures.

While the number of case studies remains limited, we can discern certain general trends that characterize how these internal microbial communities react and adapt to various environmental stimuli. For example, studies in Codonopsis pilosula indicated increased Shannon and Chao indices of root endophytes[44,45]. Notably, the bacterial community showed a significant increase in Rhizobiales, while the fungal community was enriched with Hypocreales[44]. Similar to those rhizosphere microbes, these microbes were implicated in the modulation of key sugar components that function in drought resistance. Similarly, based on research in model plants, it is reasonable to hypothesize that salt stress could lead to a significant reduction in endophyte diversity. There may, concurrently be a recruitment of microorganisms which function in energy and carbohydrate metabolism, which are essential for the plant adaptation to saline conditions[10,46]. These cases again highlight the beneficial roles of specific microbial taxa enriched under stress conditions, can provide enhanced support for plant acclimation. Moreover, different from the response of rhizosphere microorganisms, Ma et al.[47] revealed a decrease in endophytic fungal diversity specifically in heavy metal-treated Symphytum officinale, with bacterial diversity being less affected. Additionally, the occurrence-network of these endophytes were also altered by heavy-metal stress, with the modular interactions of bacteria strengthened but those of fungi weakened, respectively. Heavy metal pollution also selectively affects microbial compositions by favoring microorganisms with specific functions, such as heavy metal transport and detoxification[47]. This is exemplified in studies on Sedum alfredii, a metal hyperaccumulating plant, which specifically recruits Cd/Zinc-resistant bacteria to enhance its own tolerance to heavy metals[48]. Moreover, under heavy metal stresses, both endophyte and rhizosphere microbiomes were dominated by members of the phylum Proteobacteria, including genera such as Pseudomonas and Serratia[49,50], further supporting the aforementioned findings. These findings underscore the importance of understanding the complex dynamics of plant-microbe interactions under stress and highlight the potential for manipulating these relationships to improve plant resilience and stress tolerance.

Collectively, these findings highlight an evolutionary strategy where plants and their associated microbiomes co-evolve to mitigate the negative effects of abiotic stresses and such interaction shapes the assembly features of microbial communities. Future research should delve into the mechanisms by which medicinal plants and their microbiomes co-evolve under stress, which could potentially inform strategies for enhancing their resilience and optimizing their cultivation.

-

In the face of hostile and unpredictable environments, plants must develop robust adaptive capabilities to ensure their survival and reproductive success. The plant-associated microbiome, often referred to as the plant's second genome, plays a pivotal role in facilitating these adaptive responses. Through a long history of co-evolution with their host, these microorganisms have formed symbiotic relationships that significantly contribute to the plant ability to withstand diverse environmental stresses[51]. This relationship extends to medicinal plants as well, where mounting evidence suggests that inoculating rhizospheric or endophytic microbes can enhance their growth and development, even under stressful conditions[17,52], as listed in Table 1. Crucially, such microbial interventions have been observed to mitigate oxidative damage caused by various abiotic stress, triggering a cascade of physiological and molecular responses that enhance the plant resilience. The modulation of reactive oxygen species, enhancement of antioxidant systems, and regulation of stress-responsive genes are among the molecular events influenced by these beneficial microbes[53]. Understanding the intricate mechanisms by which these microorganisms confer medicinal plants with abiotic stress resistance is essential for advancing our knowledge of plant-microbe interactions and optimizing cultivation practices in the face of environmental adversity.

Table 1. Role of beneficial microorganisms in aiding host plant resisting abiotic stresses.

Stress type Strain/microbes Medicinal plant Mechanistic function Ref. Drought AMF Pelargonium graveolens, Glycyrrhiza uralensis; Camellia sinensis Activation of antioxidant systems Xie et al.[54]; Amiri et al.[55]; Wang et al.[56] Poncirus trifoliate; Osmotic regulation Wu et al.[57] Nicotiana tabacum;

Cinnamomum migaoActivation of antioxidant systems;

osmotic regulationBegum et al.[58];

Yan et al.[59]Ephedra foliata Boiss Activation of antioxidant systems; osmotic regulation; regulating IAA, GA and ABA levels Al-Arjani et al.[60] Poncirus trifoliate; Regulating root development;

regulating IAA and ABA levelsLiu et al.[61];

Zhang et al.[62]Glycyrrhiza uralensis Regulating aquaporin expression; regulating ABA level Xie et al.[63] DES Lycium ruthenicum, Glycyrrhiza uralensis Regulating root development, nutrient uptake and regulating soil microbiome assembly He et al.[20]; He et al.[64]; He et al.[65] Glycyrrhiza uralensis Regulating IAA production and ACCD activity Ahmed et al.[66] DSE+ Trichoderma viride Astragalus mongholicus Regulating soil microbial assembly He et al.[67] Bacillus sp. Glycyrrhiza uralensis; Activation of antioxidant systems Xie et al.[68] Bacillus sp. Trigonella foenum-graecum Enhancing ACCD activity;

beneficial microbial colonizationBarnawal et al.[69] Bacterial combination/

syncomsAstragalus mongholicus Activation of antioxidant systems Lin et al.[70] Mentha piperita; Hyoscyamus niger Activation of antioxidant systems Chiappero et al.[71]; Ghorbanpour et al.[72] Mentha pulegium Activation of antioxidant systems;

regulation of ABA and flavonoid levelsAsghari et al.[73] Ociumum basilicm Osmotic regulation Heidari et al.[74] AM fungi and PGPB Lavandula dentata Regulation of IAA levels and ACCD activity Armada et al.[75] Trigonella foenum-graecum Activation of antioxidant systems; osmotic regulation; regulation of JA levels Yue et al.[76] Echinacea purpurea Regulation of nutrient uptake Attarzadeh et al.[77] Glycyrrhiza Regulation of nutrient uptake; beneficial microbial colonization Hao et al.[78] Myrtus communis Regulation of nutrient uptake; antioxidant system activation Azizi et al.[79] Salt stress AMF Chrysanthemum morifolium Regulation of nitrogen uptake Wang et al.[80] Ocimum basilicum Activation of antioxidant systems; osmotic regulation; regulation of the K+/ Na+ ratio Abd-Allah and Egamberdieva[81] Trifoliate orange Enhanced aquaporin expression Cheng et al.[82] Ocimum basilicum Activation of antioxidant systems Yilmaz et al.[83] DES Artemisia ordosica Activation of antioxidant systems; IAA production; regulation of the K+/ Na+ ratio Hou et al.[84] Trichoderma asperellum; Priestia endophytica Lycium chinense;

Trigonella foenum-graecumRegulating nitrogen uptake and assimilation Yan et al.[85];

Sharma et al.[86]Streptomyces sp. Glycyrrhiza uralensis Activation of antioxidant systems Li et al.[87] Glutamicibacter sp. Limonium sinense Activation of antioxidant systems; osmotic regulation; regulation of the K+/ Na+ ratio; promotion of flavonoid synthesis Qin et al.[88] Bacillus sp.;

Streptomyces sp.; Azotobacter sp.Limonium sinense; Glycyrrhiza glabra; Iranian Licorice Activation of antioxidant systems; osmotic regulation; regulation of the K+/ Na+ ratio Xiong et al.[39];

Qin et al.[89];

Mousavi et al.[90];

Mousavi et al.[91]Paenibacillus sp. Panax ginseng Activation of antioxidant systems; osmotic regulation; regulation of ABA level Sukweenadhi et al.[92] Achromobacter sp. Catharanthus roseus Activation of antioxidant systems;

enhanced ACCD activityBarnawal et al.[93] Brachybacterium sp. Chlorophytum borivilianum Regulation of IAA level, ABA level and ACCD activity Barnawal et al.[94] Bacterial combination/ Syncoms Bacopa monnieri; Galega officinalis Regulation of the K+/ Na+ ratio Pankaj et al.[95]; Egamberdieva et al.[96] Phyllanthus amarus;

Coriandrum sativumActivation of antioxidant system Joe et al.[97];

Al-Garni et al.[98]Bacopa monnieri; Salicornia sp.; Capsicum annuum Osmotic regulation Bharti et al.[99]; Razzaghi Komaresofla et al.[100];

Sziderics et al.[101]Coriandrum sativum Regulation of the K+/ Na+ ratio;

activation of antioxidant systemsRabiei et al.[102] Glycyrrhiza uralensis Activation of antioxidant systems;

regulation of nutrient uptakeEgamberdieva et al.[103] Mentha arvensis Activation of antioxidant systems; regulation of nutrient uptake; regulation of the K+/ Na+ ratio; regulation of ACCD activity and siderophore production Bharti et al.[104] Medicago sativa Regulation of the IAA level Saidi et al.[105] Pistacia vera Regulation of the K+/ Na+ ratio; regulating IAA level, ACCD activity and siderophore production Khalilpour et al.[106] Fungi and PGPB Ocimum sanctum Activation of antioxidant systems;

regulation of the ACCD activitySingh et al.[107] Acacia gerrardii Regulation of the nutrient uptake;

regulation of the K+/ Na+ ratioHashem et al.[108] Artemisia annuaitalic;

Sesamum indicumActivation of antioxidant systems; osmotic regulation Arora et al.[109]; Khademian et al.[110] Heavy metal stress Halomonas sp Ligusticum chuanxiong Reduction of the heavy-metal uptake and regulating rhizosphere microbial assembly Li et al.[111] Piriformospora sp. Piriformospora indica Improving tolerance; regulation of rhizosphere microbial assembly Rahman et al.[112] Rhizobia Robinia pseudoacacia Improving tolerance;

regulation of rhizosphere microbial assemblyFan et al.[113] Sphingomonas sp. Sedum alfredii Activation of antioxidant systems Pan et al.[114] Burkholderia sp. Sedum alfredii Regulating translocation ability Chen et al.[115] Leifsonia sp. Camellia sinensis Regulation of rhizosphere microbial assembly Jiang et al.[116] Pseudomonas sp. Solanum nigrum Regulation of nutrient uptake; recruiting beneficial bacteria Chi et al.[117] Microbial inoculant Panax quinquefolium;

Salvia miltiorrhizaReduction of heavy-metal uptake;

regulation of rhizosphere microbial assemblyCao et al.[118];

Wei et al.[119]Nutrient deficiency AMF Glycyrrhiza uralensis Regulation of P and K uptake; improving nutrient utilization Chen et al.[120] Bacillus sp. Mentha arvensis Improving P solubilization Prakash and Arora[121] Bacillus sp. Camellia sinensis Regulation of K utilization Pramanik et al.[122] Serratia sp. Achyranthes aspera Improving P solubilization, IAA level and siderophore production Devi et al.[123] Bacterial combination/syncoms Angelica dahurica Regulation of nutrient uptake Jiang et al.[40] Astragalus mongolicus Regulation of nutrient uptake; regulation of rhizosphere microbial assembly Shi et al.[124] Camellia sinensis Regulating root development;

Regulation of the N uptakeXin et al.[125] Glycyrrhiza uralensis Regulation of nutrient uptake, IAA level and siderophore production Li et al.[126] Heat stress Soil suspension Atractylodes lancea Recruiting specific endophytic bacterial Wang et al.[127] Chilling stress Fungi and PGPB Ocimum sanctum Regulation of nutrient uptake and the ACCD activity; osmotic regulation Singh et al.[128] Flooding stress Bacterial

combination/syncomsOcimum sanctum Regulation of the ACCD activity Barnawal et al.[93] Drought stress

-

Diverse microorganisms can form symbiotic relationships with plants and provide benefits under drought stress conditions. Among these, arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungi are particularly acknowledged for their critical role in enhancing plant drought tolerance. For instance, extensive studies have demonstrated the positive role of AM fungi in enhancing stress tolerance in plants such as Glycyrrhiza uralensis[63,129], Ephedra foliata[60], and Poncirus Trifoliate[57] under drought stress. This benefits mainly evident in the increased growth rate, photosynthesis rate as well as the higher water content. Mechanistically, AM fungi enhance plant drought resistance by activating antioxidant defense systems[59,60,130] and facilitating the synthesis of osmotic substances such as sucrose and proline[57]. AM fungal incubation can also improve water absorption of G. uralensis through the upregulation of expression of PIP gene that related to aquaporin[63]. Interestingly, studies on Poncirus trifoliate have demonstrated that AM fungi incubation increases root endogenous hormone (e.g. abscisic acid, indole-3-acetic acid and brassinosteroids) levels, and thus promotes root hair density and diameter[61,62]. Such an effect is partly associated with the down-regulation of root auxin efflux carriers (PtPIN1 and PtPIN3) and up-regulation of root auxin influx carriers (PtABCB19 and PtLAX2) under drought stress. Moreover, via combined transcriptome and metabolome analysis, Xie et al.[54] demonstrated that AM-induced plant drought tolerance was primarily linked to the accumulation of root phenolic compounds and flavonoids. In addition to AM fungi, dark septate endophytes (DSE) have also been demonstrated to enhance biomass formation and root development in medicinal plants under drought stress, as seen in G. uralensis[20,65], and Lycium ruthenicum[64]. DSE appear to regulate plant drought tolerance by direct plant interactions and by enriching specific composition of soil microbial communities, including AM fungi, gram-negative bacteria, and actinomycetes. Bacterial inoculants also exhibit positive effects on plant drought tolerance via varying mechanisms. For instance, inoculation with Bacillus sp.[68,76] or Pseudomonas sp.[72] can mitigate lipid oxidation by enhancing the antioxidant enzyme activity or the oxidant content in the host plant. These beneficial bacteria also contribute to osmotic adjustment by increasing proline or soluble carbohydrates levels[72,74]. Furthermore, certain ACC deaminase-containing bacteria can enhance plant resistance to drought by lowing ethylene levels[69], while the activation of hormone-mediated defense pathways, such as those involving jasmonic acid (JA), is equally important[76].

The co-inoculation of diverse microorganisms, moreover, more effectively enhances plant tolerance due to their mutualistic interaction. For instance, the combined inoculation of DSE and Trichoderma viride has been shown to markedly enhance the growth and drought tolerance of Astragalus mongholicus[67]. Further evidence of the benefits of microbial co-inoculation comes from studies on Astragalus mongholicus[70], Mentha piperita[71], and M. pulegium[73], where various bacterial combinations have been documented to exert positive effects. These synergistic interactions are particularly prominent in bacterial-fungal combinations, which mitigate oxidative damage induced by drought stress by enhancing nutrient uptake and accumulation, while also reducing ethylene levels[78,131]. These findings suggest the importance of microbial diversity and the potential for mutualistic relationships between different microorganisms in improving plant resilience. The importance of microbial diversity is further demonstrated by a previous study showing significantly improved growth and drought resistance in Atractylodes lancea when incubated with an entire soil microbial community[21]. The enhanced growth and drought tolerance observed in plants inoculated with these microbial combinations highlight the potential of harnessing microbial diversity and synergies for boosting plant stress tolerance.

Salt stress

-

Salt stress is a widespread abiotic stressor that significantly influences plant growth and quality worldwide[132]. While it induces osmotic stress in plants similar to drought stress, the primary damage derives from ion imbalance and toxicity, which can severely impair plant productivity[133]. In the context of plant-microorganism interactions, various strategies are employed to mitigate this complex osmotic stress. Similar to their role in addressing drought stress, AM fungi represent a key strategy for mitigating salt stress in medicinal plants. Via meta-analysis, previous studies have shown that plants inoculated with AM fungi, either alone or in combination with other bacteria, exhibit better performance under salt stress compared to non-mycorrhizal plants[134,135]. This beneficial effect has been observed in medicinal plants such as Artemisia annua[109], Acacia gerrardii[108], and Ocimum basilicum[81]. The improved resilience of these medicinal plants is largely attributed to several factors. Crucially, AM fungi enhances nutrient uptake, leading to increased levels of essential elements such as N, P, and microelements while reducing the concentrations of harmful ions such as Na+ and Cl−[80,110]. This also results in a more favorable potassium/sodium (K+/Na+) ratio. Equally important is the activation of antioxidant enzyme activities contributes to the enhanced stress tolerance. Additionally, a study on peanut demonstrated that combined inoculation of AM and Lactobacillus plantarum under salt stress modulated signal transduction pathways, including those involving phytohormone synthesis and mitogen-activated protein kinases[136]. This finding highlights the underlying molecular mechanisms involved in microorganism-regulated plant salt tolerance, similar to that observed in the salt tolerance promoted by DES in G. glabra[137]. Moreover, Trichoderma has also been shown to positively impact medicinal plant health, primarily through enhanced nutrient, especially N, absorption. This is accompanied by increased activities of N assimilation enzymes, including nitrate reductase, nitrite reductase, and glutamine synthetase[85].

Notably, N-fixing rhizobia and actinomycetes have garnered considerable interest for their roles in producing antioxidants and osmoregulatory substances[87,91]. Rhizobia enhance plant salt tolerance by improving N absorption and assimilation, while actinomycetes exhibit significant resilience to water shortage and osmotic stress. Similarly, other plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPRs) also exhibit great potential in enhancing plant salt tolerance. For instance, bacteria such as Bacteroidetes, Bacillus, and Pseudomonas can activate the entire defence system of medicinal plants under salt stress by facilitating ion transport, boosting antioxidant production, and aiding in osmotic regulation[39,96,138]. Furthermore, the synergistic effects of co-inoculating these beneficial bacteria warrant significant consideration. For instance, co-inoculation of rhizobia and Pseudomonas or Bacillus species can effectively mitigate hydrogen peroxide production under salt stress by enhancing N content, antioxidant capacity, and free radical scavenging ability[97,103]. Incorporating multiple beneficial bacteria or a combination of growth-promoting bacteria and fungi may further strengthen plant capacity to tolerant salt stress through diverse regulatory mechanisms. Specifically, these beneficial microbes primarily elevate the K+/Na+ ratio by promoting K+ absorption and thus inhibiting Na+ uptake, which is also accompanied by the activation of antioxidant systems and the absorption of other nutrients to synergistically improve plant resistance[100]. Additionally, these bacteria can support plant growth under saline conditions through the production of extracellular polysaccharide, ACC deaminase or siderophores (iron carriers)[99,106].

Heavy metal-stress

-

When addressing heavy metal pollution, plant-microorganism systems primarily adopt two strategies: inhibiting the absorption of heavy metals by plants and improving plant tolerance to these metals, aiming to mitigate the associated negative effects. For example, Li et al.[111] demonstrated that Halomonas sp. could reduce the bioavailability of cadmium and phoxim in soil and plants, thereby improving rhizome biomass and reducing oxidative damage. Similarly, microbial inoculant have been found to reduce the accumulation of heavy metals in the roots of medicinal plants such as Panax quinquefolium[118] and Salvia miltiorrhiza[119], thus enhancing their survival efficiency. These findings highlight the potential of microbial inoculation as a sustainable and eco-friendly strategy for mitigating heavy metal pollution in agricultural ecosystems. Furthermore, microbial inoculation not only facilitates metal sequestration but also enhances plant tolerance to heavy metals by modulating plant physiology and biochemistry through various mechanisms. For instance, Chen et al.[115] demonstrated that Sphingomonas inoculation confers Sedum alfredii tolerance to cadmium stress and reduces oxidative damage in vivo through organic acids secretion. Additionally, the inoculation with multiple bacterial species has been shown to promote plant tolerance to aluminum stress by upregulating stress-related gene expression, such as AtAIP, AtALS3, and AtALMT1, and by recruiting aluminum-resistant and growth-promoting bacteria[116,138]. Comparable effects have been observed under arsenic stress, where beneficial microorganisms like Bacillus sp., Nitrospira sp., and Microbacterium sp., contributing to plant growth and tolerance under heavy metal stress[118]. Conversely, some beneficial bacteria enhance the transport efficiency of heavy metals in plants, promoting their accumulation in aboveground parts while simultaneously improving plant tolerance[112,139]. This is largely attributed to the reassembly of the rhizosphere microbiome, particularly the enrichment of beneficial microorganisms such like Mesorhizobium and Streptomyces genera[112,113]. These findings suggest that microbial inoculants aid in managing and mitigating the negative effects of heavy metals by cultivating a more robust and diverse microbial community. Thus, harnessing the beneficial interactions between plants and microorganisms can enhance plant resilience to heavy metal stress and promote ecosystem health.

Nutrient deficiency

-

Beneficial rhizobacteria are well-established for their critical role in enhancing nutrient uptake and utilization efficiency in plants. Investigations on Astragalus mongolicus[124] and G. uralensis[126] have elucidated that inoculating plants with rhizobacteria combinations can increase the mineral nutrients uptake, thus enhancing biomass production under low-nutrient conditions. Similar findings have been recorded in Angelica dahurica and Camellia sinensis, where the application of synthetic microbial communities (Syncoms) markedly improved N uptake and assimilation, concomitant with the theanine synthesis, under low-N conditions[40,125]. Moreover, bacteria possessing P-solubilizing properties may act as pivotal regulator of plant growth under low-P conditions. These bacteria facilitate root development and aboveground biomass formation by elevating rhizosphere soil P content through rhizosphere acidification and phosphatase excretion into the rhizosphere[121,140]. Notably, AM fungi has exhibited significant efficacy in enhancing P nutrient absorption, which typically resulting in reduced soil P levels and enhanced plant P uptake, consequently promoting plant growth under low-P conditions[120,141]. Furthermore, studies on Achyranthes aspera have highlighted the plant growth-promoting capabilities of Serratia sp., which produce siderophores under iron-deficient conditions[123]. Additionally, their roles in P solubilization and indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production further contribute to plant growth. Given the significant contributions of beneficial rhizobacteria to plant nutrient uptake and growth enhancement, it is evident that harnessing these microbial interactions can develop innovative strategies to address global nutrient heterogeneity and to establish more resilient agricultural systems.

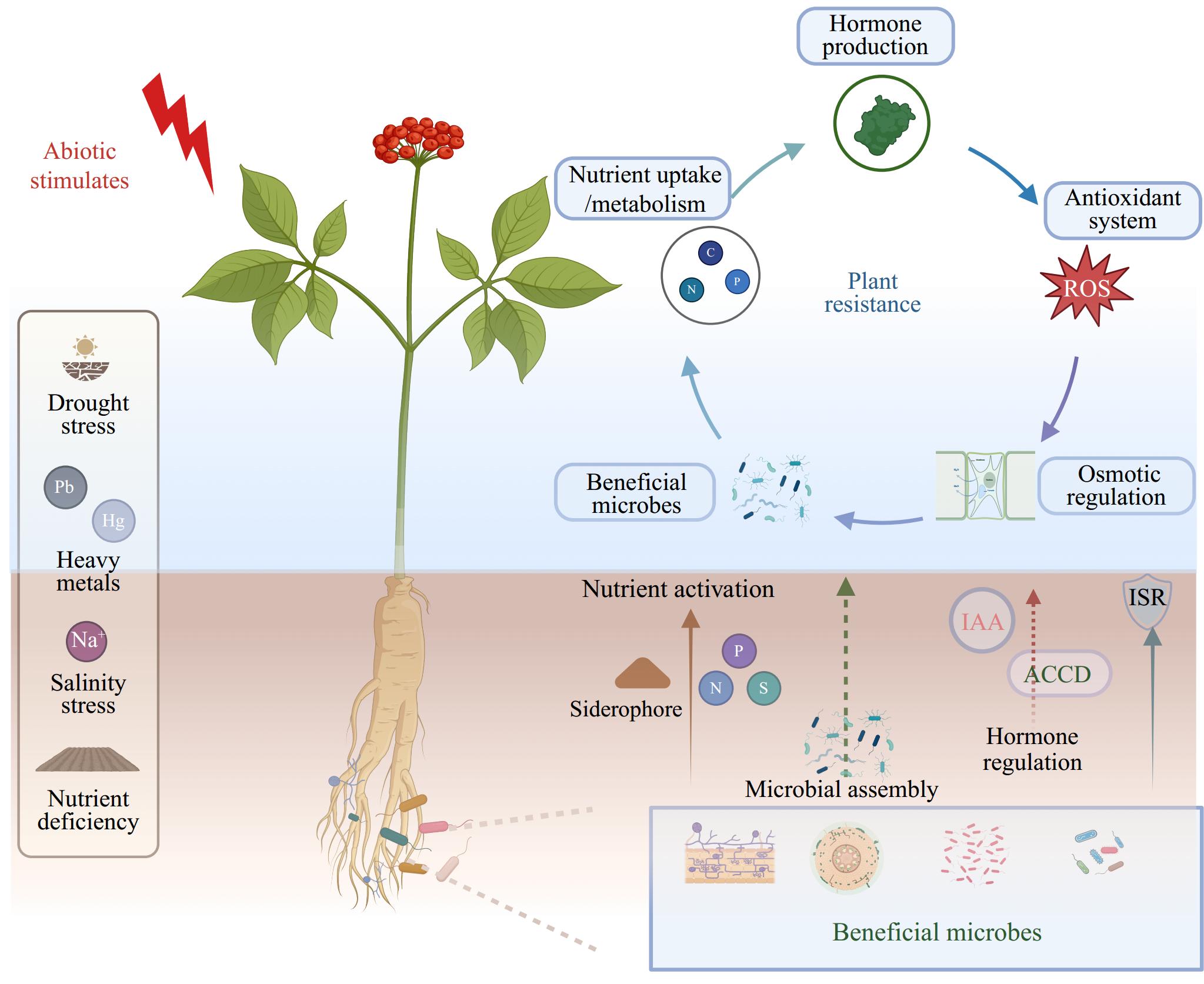

Additionally, microbial inoculation has been reported to enhance the resilience of medicinal plants under other stress conditions, including chilling[127], heat[128], and waterlogging[93] stresses. The beneficial effects are primarily attributed to processes such as decreased ethylene production, improved nutrient absorption, and the recruitment of specific bacteria. Together with the above instances, it is evident that these beneficial microorganisms can significantly impact plant physiology and biochemistry processes via soil nutrient remobilization, hormone level regulation and reshaping of microbial community (Fig. 1). Furthermore, while research on medicinal plants is limited, studies in model crops such as Arabidopsis[142] and Oryza sativa[143] suggest that beneficial microorganisms can enhance plant tolerance by triggering induced systemic resistance (ISR), which stimulates the plant defense system, leading to the upregulation of genes involved in hormone regulation and stress responses, such as dehydrin (DHN), glutathione S-transferase (GST) and responsive to desiccation 29B (RD29B). These events comprehensively highlighted the pivotal role of employing beneficial microorganisms in advancing sustainable agricultural development under the challenging global climate changes. Thus, it is imperative to further investigate the efficacy of different types of microorganisms or their synthetic in mitigating diverse abiotic stresses as well as the underlying mechanisms. This will enable the development of corresponding microbial solutions for agricultural production under specific stress.

Figure 1.

Mechanistic insights into how beneficial microbes enhance medicinal plant resilience to abiotic stress.

Under abiotic stress conditions, diverse microorganisms in the rhizosphere or within endophytic compartments—such as fungi and bacteria—play a crucial role in enhancing the adaptability of medicinal plants. These microorganisms can improve nutrient absorption and metabolism by enhancing soil nutrient availability. Additionally, their ability to produce auxin or ACC deaminase enzymes influences plant hormone production, which subsequently affects downstream resistance events. Furthermore, microbial inoculations can trigger induced systemic resistance (ISR) and then enhance the overall resilience of medicinal plants by altering their antioxidant system, osmotic regulation, and hormone balance. Under specific stress conditions, such as heavy metal pollution, these beneficial microorganisms can re-assemble the microbial community further to amplify their positive effects on the host plant.

-

In addition to growth, development, and stress adaptability, the variation in specific secondary metabolites in medicinal plants is equally important, as these compounds dictate their medicinal quality and economic value[144]. Previous studies have shown that under abiotic stresses, the levels of these compounds can either increase or decrease. The decreases may result from metabolic disruptions under severe stress condition, while increases are primarily attributed to the concentration effect resulting from reduced plant biomass, especially under drought conditions[145]. This prevalent trade-off between plant growth and differentiation complicates the simultaneous enhancement of both plant stress adaptation and medicinal compound concentration. Hence, given plant-microbe interactions, it is imperative to further comprehend the effects of beneficial microbial inoculation on the content of valuable compounds in medicinal plants and their potential mechanisms.

Notably, numerous previous studies have illustrated that the single or combined inoculation of these microorganisms effectively alters the accumulation of specific metabolites under abiotic stresses, while also promoting plant growth (Table 2). For example, under drought stress, favorable results have been observed with the inoculation of DES[20], AM fungi[63], and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens[76] on the contents of glycyrrhizic acid, glycyrrhizin and liquiritin in Glycyrrhiza uralensis, alongside enhanced activities of key enzymes involved in licorice synthesis pathway. Similarly, investigations on Nicotiana tabacum and Pelargonium graveolens have indicated that AMF treatment significantly enhanced both the content and yield of essential oil[55,58]. Furthermore, studies have documented the positive effects of co-inoculation of two or more bacteria on secondary metabolite production in various medicinal plants under drought stress. This includes increased astragaloside IV and calycosin-7-glucoside content in Astragalus mongholicus[70], essential oil contents in Mentha pulegium[73], and tropane alkaloids in Hyoscyamus niger[72]. Such beneficial effects have also been recorded when plants were subjected to salt stress. For example, an examination of Artemisia annua showed that combined treatment with AM fungi and beneficial bacteria enhances both artemisinin accumulation and host salt resistance[109]. Similar results have been reported for specific metabolites in other medicinal plants, such as saponin[99], flavonoid[88], and glycyrrhizic acid[91]. Mechanistically, these effects may be attributed to an increase in plant sugar content under osmotic stress[91,92,107], as sugars play a central role as precursors for secondary C metabolism. Additionally, microbial inoculation may modulate plant hormone balance through ISR, thereby influencing the synthesis of secondary metabolites biosynthesis[146]. This was also evidenced by Yue et al.[76], who highlighted the role of JA in Bacillus sp.-promoted flavonoid and terpenoid synthesis.

Table 2. Role of beneficial microorganisms in the contents of main medicinal compounds in medicinal plants subjecting to abiotic stresses.

Stress type Strain/microbes Medicinal plant Contribution Ref. Drought AMF Glycyrrhiza uralensis Improving glycyrrhizin and liquiritin production;

up-regulation of the expression of key genes (e.g. squalene synthase (SQS1), β-amyrin synthase (β-AS)

and cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYP88D6

and CYP72A154)Orujei et al.[129];

Xie et al.[63]Nicotiana tabacum/ Pelargonium graveolens Enhancement of oil content; up-regulation of the expression of key genes Begum et al.[58]; Amiri et al.[55] DSE Glycyrrhiza uralensis Elevation of glycyrrhizin and glycyrrhizic acid content; regulation of the N and P content He et al.[147] Bacillus sp. Glycyrrhiza uralensis Enhancement of the total flavonoids, total polysaccharide and glycyrrhizic acid content; up-regulation of the expression of key enzymes (e.g. lipoxygenase and phenylalanine ammonia-lyase); simulation of JA-synthesis Xie et al.[68];

Yue et al.[76]Bacterial combination/ Syncoms Astragalus mongholicus Enhancement of the astragaloside IV and calycosin-7-glucoside content Lin et al.[70] Mentha pulegium Improving phenolic, flavonoid and oxygenated monoterpenes production Asghari et al.[73] Hyoscyamus niger Improving tropane alkaloid production Ghorbanpour et al.[72] Salt AMF Glycyrrhiza glabra Elevation of the glycyrrhizin and terpenoid precursors production Amanifar et al.[148] Priestia endophytica Trigonella foenum-graecum Improving phenolic compounds and trigonelline synthesis and N fixation Sharma et al.[86] Azotobacter sp. Glycyrrhiza glabra Enhancement of the glycyrrhizic acid and glabridin production Mousavi et al.[91] Bacterial combination/ syncoms Artemisia annua Enhancement of the artemisinin production; improving N and P contents Arora et al.[109] Foeniculum vulgare Enhancement of the essential oil production Mishra et al.[149] Bacopa monnieri Enhancement of the bacoside A production Pankaj et al.[95] AM fungi and PGPB Sesamum indicum Improving phenolic, flavonoid, sesamin and sesamolin production Khademian et al.[110] Mentha arvensis Enhancement of essential oil content Bharti et al.[150] Heavy-metal stress Microbial inoculant Panax quinque folium Enhancement of the ginsenoside production; regulation of the rhizo-microbial structure and composition Cao et al.[118] Microbial inoculant Salvia miltiorrhiza Elevation of the total tanshinones content; recruiting beneficial microorganisms Wei et al.[119] N-deficiency Bacterial combination Angelica dahurica Enhancement of the furanocoumarin production Jiang et al.[40] Astragalus mongolicus Enhancement of the flavonoids, saponins, and polysaccharides contents Shi et al.[124] P-deficiency AMF Hypericum perforatum Enhancement of the glycyrrhizic acid, liquiritin, isoliquiritin, and isoliquiritigenin contents; regulation of the nutrient absorption Lazzara et al.[151] Polygonum cuspidatum Enhancement of the chrysophanol, emodin, polydatin, and resveratrol contents; regulation of the nutrient absorption Deng et al.[141] Nutrient-deficiency AMF Glycyrrhiza uralensis Elevation of the isoliquiritin and isoliquiritigenin content; enhancement of the P, K and microelements absorption Chen et al.[120] Heat stress Soil suspension Atractylodes lancea Enhancement of the hinesol, β-eudesmol, atractylon and atractylodin content, up-regulation of the expression of key genes (e.g. 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase (DXS), farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FPPS), 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme (HMGR)); enrichment of specific beneficial bacteria Wang et al.[127] The promotion of nutrient absorption by microbial incubation is as also considerable with prior studies having identified correlations between N and P contents and the terpenoid synthesis in G. uralensis[147] and Artemisia annua[109]. Additionally, alkaloid levels can be actively regulated by exogenous bacterial inoculation under salt stress, attributed to the induction of N fixation mechanisms in plants, thereby enhancing trigonelline biosynthesis[86]. Therefore, given the nutrient uptake-promoting effects of these microorganisms and the critical roles of N and P in secondary metabolite synthesis, these microorganisms are anticipated to have a substantial impact on the metabolic regulation of plants under nutritional stresses. Indeed, researchers have found that Syncoms derived from bacteria isolated under N-deficient conditions significantly improve the N utilization efficiency of Angelica dahurica and enhance the synthesis of furanocoumarins[40]. This stimulatory function is linked to the capacity of functional bacteria to enhance nutrient utilization. Supportively, N-fixing bacteria such as Bacillus and Arthrobacter have been shown to enhance nutrient uptake and accumulation, as well as elevate the flavonoid, saponin, and polysaccharide contents in Astragalus mongolicus[124]. An investigation on tea plants demonstrated that synthetic communities lacking N-fixing bacteria could not effectively facilitate theanine synthesis[125], further demonstrating the critical role of N in microbial regulation of secondary metabolism. P absorption and utilization are equally important for the synthesis of C-based secondary metabolites, which serve as vital components for acetyl-CoA, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate, as well as isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP)/dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP), the common substrate for both the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) and mevalonate (MVA) pathways[152]. Such results have been extensively documented with AM inoculation, which enhances terpenoid production through enhaced P uptake. For instance, AM has been shown to effectively increase the levels of hypericin and pseudohypericin in Hypericum perforatum[151], as well as chrysophanol, emodin, polydatin, and resveratrol concentrations in Polygonum cuspidatum[141], under low phosphorus conditions. Moreover, a study on Mentha arvensis revealed that Bacillus can increase essential oil production by solubilizing P[121], indicating that combining nutrients with microbial agents can more effectively enhance both the yield and quality of medicinal plants.

Furthermore, there is evidence from limited studies documenting the beneficial effects of microbial inoculation on the quality of medicinal plants under other stress conditions. For example, the application of microbial inoculants significantly increased the accumulation of total ginsenosides in Panax quinquefolium[118] and total tanshinones in Salvia miltiorrhiza[119] under heavy metal stress, offering new approaches for cultivating medicinal plants in contaminated regions. Furthermore, a study on heat stress has demonstrated the remarkable resilience conferred by inoculation with soil microbial communities, along with the accumulation of volatile medicinal compounds in the roots of Atractylodes lancea[127]. This observed enhancement was accompanied by the upregulation of key genes such as farnesyl diphosphate synthase (FPPS), 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase (HMGR), and 1-deoxy-d-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase (DXS), shedding light on the molecular mechanisms underlying microbial-mediated stress response and secondary metabolite production. Importantly, these investigations have identified simultaneous changes in the structure and composition of rhizosphere and endophytic microbial communities. These changes would selectively recruit microbes with specialized functions, thereby enhancing secondary metabolic processes under stress conditions. These findings not only deepen our understanding of plant-microbe interactions, but also hold significant implications for the sustainable production of high-quality medicinal plants in the face of environmental challenges. Notably, these elevated secondary metabolites may also be helpful in enhancing host plant resistance to abiotic stresses. However, evidence linking microbes, secondary metabolites and medicinal plant resistance is largely lacking and warrants further investigations in the future.

-

As the second genome of plants, plant-associated microorganisms, including rhizospheric and endophytic ones, will respond to environmental stresses correspondingly with plants and thereby critically contribute to plant adaptability. Faced with these stresses, microorganisms respond by altering their community diversity and assembly processes in a manner that is mainly mediated by root exudates. As a result, the specific core microorganisms recruited under stresses will favour host coping with the environmental stresses, as well as the improved quality formation of medicinal plants. Such results provide novel insights for cultivating high-quality medicinal plants under stressful conditions. The underlying mechanisms are multifaceted, encompassing the modulation of plant nutrient utilization and hormone production associated with the microbial functions such as nitrogen fixation and ACCD enzyme activity. These microorganisms also play a role as inducers of ISR in plants, thus stimulating their defense against various stresses. Equally important is the re-assembly of the microbial community structure through interaction with other microorganisms, thus enhancing the overall resilience of the plant-microbiome system. In the future, it is imperative to strength the research into the specific microbial communities associated with medicinal plants, which includes the development of agent or bio-fertilizer products associated with these beneficial microorganisms or the Syncoms, thus ensuring the robust growth and quality of medicinal plants in the face of increasingly challenging environmental conditions.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32101842), the Open Fund of Jiangsu Key Laboratory for the Research and Utilization of Plant Resources (JSPKLB202303) and the Max Planck Society.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Sun Y, Fernie AR; literatures collection and analysis: Sun Y, Yuan H; draft manuscript preparation: Sun Y, Fernie AR. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2024 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Sun Y, Yuan H, Fernie AR. 2024. Harnessing plant-associated microorganisms to alleviate the detrimental effects of environmental abiotic stresses on medicinal plants. Medicinal Plant Biology 3: e024 doi: 10.48130/mpb-0024-0023

Harnessing plant-associated microorganisms to alleviate the detrimental effects of environmental abiotic stresses on medicinal plants

- Received: 09 July 2024

- Revised: 30 August 2024

- Accepted: 19 September 2024

- Published online: 25 November 2024

Abstract: Medicinal plants frequently encounter environmental challenges such as drought, salinity, and heavy metal pollution, all of which are aggravated by the ongoing global climate change. Plants can alleviate the negative effects of these stresses by interacting with microorganisms both in the rhizosphere and within the plant itself. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the responses of microbial communities to these challenges and their impact on plant resistance and quality. In this study, microbial community structures and assembly changes are explored in response to abiotic stresses and the functional mechanisms underlying beneficial microorganism’s enhancement of plant tolerance are elucidated. These include activation of the antioxidant system activation, osmotic regulation, hormone synthesis, nutrient utilization, and recruitment of other beneficial microbes. Furthermore, these microorganisms significantly improve the quality of medicinal plants under abiotic stresses by enhancing the synthesis and accumulation of key secondary metabolites. While these findings provide functional insights into the beneficial effects of microorganisms on medicinal plants under stressful conditions, further research is necessary to be able to routinely apply microbial resources as a means to enhance plant adaptability and quality.

-

Key words:

- Medicinal plants /

- Abiotic stress /

- Secondary metabolism /

- Microbiome assembly /

- Plant resistance