-

Yams (Dioscorea spp.), an important class of horticulture crops are monocotyledonous plants that contain more than 600 species[1]. D. alata, D. cayenensis and D. rotundata are by far the major cultivated species worldwide, with D. rotundata contributing the most to production and D. alata being the most widely grown[2]. Yam tubers are rich in carbohydrates, proteins, vitamin C, and are storable for months after harvesting[3]. In some African countries, also known as the 'Yam belt', such as Nigeria, Benin, Ghana, Togo, and Guinea, yams are a staple food for millions of people[3,4]. In other regions of Asia, the Pacific and Latin America, yams are an important source of income for around 300 million people[5]. Despite the local significance, yams have long been regarded as orphan crops that have been overlooked by researchers. However, global production of yam has doubled in the past two decades, driven by the need to combat climate change and dietary diversity[6]. The rise in global production of yam is not as a result of increased yield per unit area such as such as rice and corn, but rather the result from the expansion of the overall planting area (FAOSTAT 2020). In recent years, to maintain a sustained increase in yam production, the genetic and molecular breeding research in yams are gradually strengthened globally. From the beginning of empirical breeding to other molecular markers such as QTL that are now more promising[2].

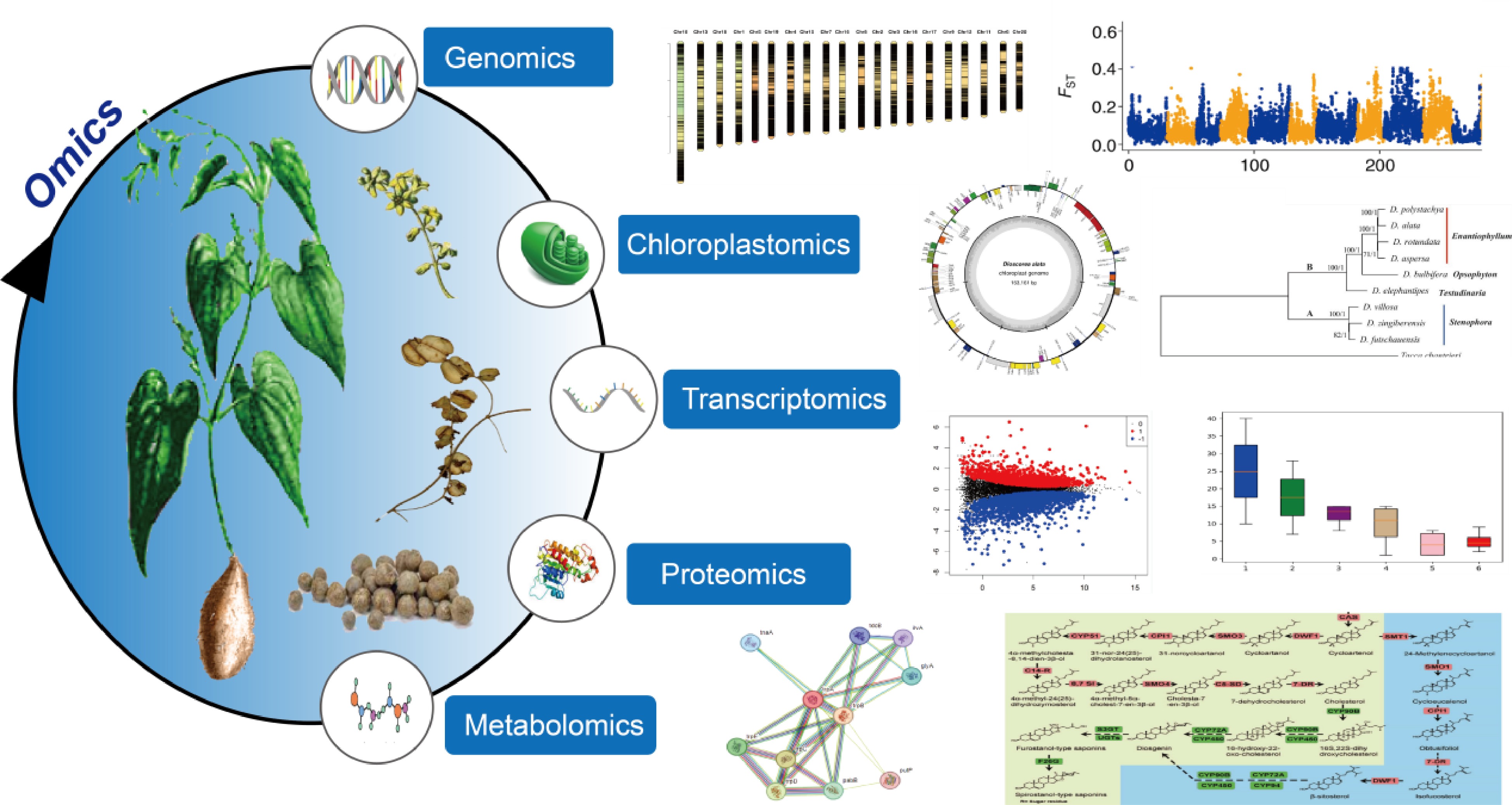

Comprehensive understanding of genetic basics and conducting genetic improvement requires the interpretation of molecular intricacy and variations at multiple levels such as genome, plastome, transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome. With the advent of sequencing technology, biology research has become increasingly dependent on datasets generated at these levels for model organisms. However, as orphan crops, yams have received little attention in omics levels, with research mainly focusing on the components of the tubers, the germplasm resource classification, and extraction of specific components, and medicinal effects[7]. For example, pollution of the environment during the extraction of Diosgenin elements[8]. When systematically controlling diseases and pests in yams, it is necessary to analyze their genetic diversity. However, standard genetic analysis methods are not applicable due to the limited number of genetic markers available and the high heterozygosity associated with their obligate outcrossing nature. Therefore, the first species of the genus Dioscorea was subjected to whole-genome sequencing, resulting in the release of the first genome of a Dioscorea species, which ushered in the era of functional genomics of Dioscorea[9]. In recent years, significant progress has been made in the genomics of the Dioscorea genus. Scientists have conducted extensive and in-depth studies on Dioscorea species from various perspectives, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolic networks (Fig. 1). This review provides the current state of genomic research on the Dioscorea genus, hoping to aid in furthering in-depth studies of the genus.

-

Although crop traits are regulated by genes, the sequencing of all genes alone provides insufficient information on which to base crop improvements such as greater yield and disease resistance[10]. Understanding the precise locations of all genes within a genome enhances the practicality of molecular marker technology. This knowledge enables the pinpointing of specific candidate genes responsible for particular traits, thereby extending the technology's utility. In the model species, such as rice and corn, it has witnessed the significant roles of genomics sequencing and analysis in the genetic improvement of crops[11]. To date, the genomes of five yam species have been sequenced and the genome assemblies of four species reached the chromosome level (Table 1). The assembled genome size ranged from 440 to 629 Mb, and the number of annotated coding genes ranged from 25,000 to 35,000. From these two sets of data, it can be seen that there is great genetic diversity among yam species. These genomics data and related analyses provide references for yam basic biology and molecular breeding.

Table 1. List of sequenced Dioscorea species genomes.

Species Assembly size (Mb) Assembly level N50 (Mb) Gene number Ref. D. rotundata 594 Chromosome 2.12 26,198 [9] D. rotundata* 584 Chromosome 23.4 34,550 [12] D. dumetorum 485 Contig 3.2 35,269 [13] D. alata 479 Chromosome 24 25,189 [3] D. zingiberensis# 480 Chromosome 44.5 26,022 [14] D. zingiberensis# 629 Chromosome 55.8 30,322 [15] D. tokoro 443 Chromosome 24 29,084 [16] * The improved genome assembly for D. rotundata; # The two assemblies from different D. zingiberensis strains. The sex determination mechanism is crucial in crop breeding, while this problem in yam has not been solved for a long time. In 2017, scientists sequenced and assembled the first genome of the Guinea yam (D. rotundata), marking a significant milestone in Dioscorea genomics[9]. Phylogenetic analysis of conserved genes illuminated the distinct nature of the Dioscorea lineage within monocotyledons, setting it apart from other groups such as Poales (rice), Arecales (palm), and Zingiberales (banana). With the genome tool, an approach was developed to conduct whole-genome resequencing of grouped segregants using F1 progeny that exhibited segregation of male and female D. rotundata plants. By the genomics analysis, a genomic region linked to female heterogametic sex determination (male = ZZ, female = ZW) was identified, and this discovery was further refined and transformed into a molecular marker for sex identification of Guinea yam plants at the seedling stage. Similarly, through genomic sequencing and analysis, the sex determination mechanism of D. tokoro was located in the middle of pseudochromosome 3, with a male heterogametic sex determination (XY) system[16].

The dissection of yam domestication history plays an important role in the interpretation of the genetic mechanisms of important agronomic trait formation. An improved version of Guinea yam reference genome, together with more than 330 accessions and its wild relatives was used to investigate its origin[12]. The analysis results revealed that diploid D. rotundata was likely evolved from a hybrid of D. abyssinica and D. praehensilis. The assessment of the genomic contributions uncovered a pronounced presence of the D. abyssinica genome within the sex chromosome of D. rotundata and a clear signature of widespread introgression within the SWEETIE gene located on chromosome 17. To explore the chromosome evolution of D. alata, the yam research community generated a highly contiguous genome assembly and a dense genetic map from African breeding populations[3,17,18]. The genomic analysis results suggest that there was an ancient allotetraploidization in the Dioscorea lineage, subsequently with extensive genome-wide reorganization. Moreover, some QTLs (quantitative trait loci) were detected for resistance to anthracnose and tuber quality traits using the genomic tools.

Although sapogenin saponins were isolated from the rhizomes of D. tokoro in the 1930s[19], its biosynthetic pathway has been a mystery. The comparative genomic analysis suggests that tandem duplication coupled with whole-genome duplication events provided key evolutionary resources for the diosgenin saponin biosynthetic pathway in D. zingiberensis[15]. Combined with transcriptome and metabolite analysis among 13 yam species, some gene expression patterns in specific metabolic pathways were found to be associated with the evolution of the diosgenin saponin biosynthetic pathway. These genes mainly involve in CYP450 family, such as CYP90B, CYP72A and CYP94. Further investigations revealed that the increased concentration of diosgenin in the yam lineage is governed by CpG islands. These islands have evolved to modulate gene expression within the diosgenin pathway, playing a crucial role in balancing the carbon flux between the biosynthesis of diosgenin and starch[14].

-

Compared to the nuclear genome, plastome, especially chloroplast genome sequences of the Dioscorea spp. are more easily sequenced and frequently used for the identification of kinship. The first chloroplast genome of yam is from D. elephantipes. As an important representative branch, it was employed to estimate phylogenetic relationships among angiosperms[20]. The chloroplast genome is only 152,609 base pairs in size, including 129 genes, 4 rRNAs, 38 tRNAs, as well as 16.72% inverted repeat (IR), 54.24% large single copy (SSC) and 12.32% small single copy (SSC) (Fig. 2a). Although chloroplast genomes are small and simple, it is still challenging to obtain complete chloroplast genomes for large-scale population genetics or phylogeographic studies. Therefore, in 2014, Mariac et al. developed an in-solution enrichment hybridization capture scheme suitable for deep multiplexing of chloroplast genomes, greatly aiding in the large-scale acquisition of complete chloroplast genome series for species[21]. Numerous Dioscorea species chloroplast genomes are stored in GenomeTrakrCP, greatly aiding subsequent research.

To ascertain the phylogenetics relationship among Dioscorea spp., more and more complete chloroplast genomes of yams were generated. In 2016, after sequencing the complete chloroplast genomes of Discorea species, a phylogenetic tree was constructed with other species and D. elephantipes and D. rotundata, showing closer phylogenetic relationships among the three D. species[22,23]. In 2018, high throughput technology was used to sequence the complete chloroplast genomes of D. aspersa, D. alata, D. bulbifera, D. futschauensis, and D. polystachya[24] and compared them with four previously studied species, finding that the chloroplast gene features and structures of these nine Dioscorea species are similar, with only slight differences in sequence length. Based on the species' chloroplast whole genomes, a phylogenetic tree was constructed, revealing the kinship relationships among the Dioscorea species. In the evolution tree, the nine species were divided into two branches. In the one branch, D. polystachya, D. alata, D. aspersa, and D. rotundata have a closer evolutionary relationship, while D. bulbifera and D. elephantipes are in a separate kinship relationship compared to the four species. In the other branch, D. villosa, D. futschauensis, and D. zingiberensis are closely related. In 2019, Magwé-Tindo et al. reconstructed complete chloroplast genomes for 14 African yam species and built a phylogenetic tree with D. rotundata as reference and D. elephantipes as outgroup species, enriching the evolutionary relationships among Dioscorea species[25]. In the following two years, different scientists continued refining the chloroplast genomes of different species. They performed phylogenetic analysis with Dioscorea species, determining the phylogenetic position. Cao et al. sequenced the whole chloroplast genome of D. persimilis and determined that D. persimilis is closely related to D. alata and D. polystachya but distantly related to D. rotundata[26], validating previous findings. Chen et al. sequenced the chloroplast genome of D. esculenta and constructed a phylogenetic tree, showing that the species is closer to D. sansibarensis[27]. Hu et al. sequenced the chloroplast genome of D. polystachya, compared it with 15 Dioscorea species, and found that D. polystachya is closely related to D. alata and D. aspersa[28]. Wonok et al. conducted structural, comparative, and evolutionary analysis of the chloroplast genomes of four native Thai Dioscorea species, providing the chloroplast genome structure and complete chloroplast gene sequences of D. depauperata, D. glabra, D. pyrifolia, and D. brevipetiolata. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that D. brevipetiolata, D. depauperata, and D. glabra are closely related to D. alata, while D. pyrifolia is more evolutionarily similar to D. aspersa[29].

In addition to the complete chloroplast genome, chloroplast DNA markers can also be used for phylogenetic analysis. A largest phylogenetic tree that consisted of 48 Dioscorea species was constructed based on the concatenated matrix of seven markers including matK, rbcL, tmL-F, psbA-tmH, rpl36-rps8, nad1, rps3 and 7 DNA (Fig. 2b)[3]. This evolutionary tree provided molecular evidence for morphological classification, and for the first time, explored the evolution of four forms—bulbils, inflorescence openness, flower color, and inflorescence structure—based on the phylogenetic tree. This study provides evidence to support classification based on morphological traits and confirms that late differentiation of bulbils in Dioscorea species can improve reproductive efficiency and enhance adaptability.

-

Transcriptomics is the study of gene regulation and its expression at the RNA level[30], which developed from expressed sequence tag (EST) sequencing to the now widely used RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq). RNA-Seq is a method for transcript quantification that allows the more precise measurement of transcript levels and their isoforms compared to other approaches. Because of the high sensitivity in the detection of gene expression, RNA-Seq is often used to provide expression evidence for gene annotation in genome sequencing projects. For the species without reference genome, RNA-seq can be independently employed to construct reference transcriptome and investigate gene regulatory functions in various biological processes.

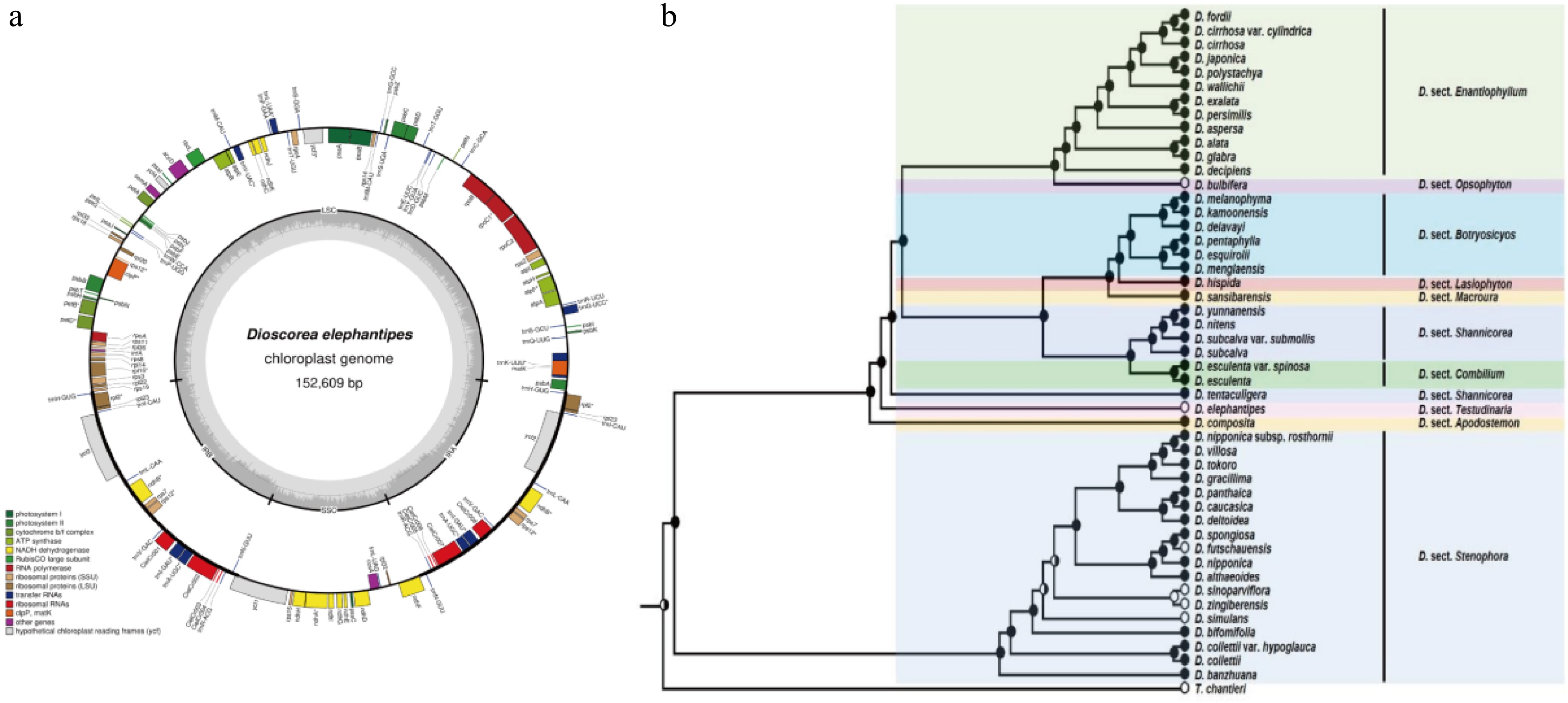

The growth and development of yam are complex, from sprouting, stem, and leaf growth, to the final expansion of the tuber, flowering, and fruiting. The genes involved in their formation and their functions are still unknown. RNA-Seq was used to study the changes in the transcriptome during the formation of D. opposita microtubers and it was found that the development of microtubers is closely related to primary metabolisms, such as starch and sucrose metabolism[31], which has important implications for the study of germination. Although transcriptomic data during stem and leaf growth have been less studied, they will be sequenced collaboratively in the construction of the reference transcriptome of yam, thereby improving its accuracy[32]. The majority of yams do not flower or flower for a very short period, and transcriptome changes in flowers during early developmental stages were identified when analyzing transcriptome data from male, female, and dioecious individuals of D. rotundata[33]. Male plants were found to flower more intensely, similar to flowering-determining genes in other species, with a conserved flowering mechanism. Based on transcriptome analysis of microtubers, regulatory genes for phytohormones were also identified and ABA was found to positively regulate tuberous growth. On this foundation, it revealed that the metabolic pathways of tuber chemicals such as flavonoids are closely related to tuber development by transcriptome analysis[7]. Tuber size is strongly associated with yam yield, and the identification of gene functions related to the tuber expansion process can help improve. It turns out that SuSy and AGPase genes regulate the conversion of sucrose to starch in storage roots, which in turn positively regulates tuber enlargement (Fig. 3a)[34]. Similar to the mechanism of tuber influence, transcriptional analysis of the developmental stages of yam bulbs in conjunction with morphological analysis revealed growth hormone, CK, and sucrose as bulb initiation signals[35].

Figure 3.

(a) Modeling the conversion between sucrose and starch during tuber amplification[34]. (b) Simplified diagram depicting the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway in yam tubers. Red arrows indicate genes that were significantly up-regulated in the purple-fleshed yam tuber. Gray indicates no change in gene expression between two tuber types[38]. (c) Putative mechanism of the PHH in D. dumetorum, blue represents GO annotation[41].

The main constituent of yam tubers is starch, which is also an excellent source of flavonoids, diosgenin elements, and other medicinal constituents, but their biosynthetic pathways are not yet known. Sequencing of transcriptome libraries of D. polystachya leaf and rhizome tissues enriched the transcriptome data of the species while revealing differences in the expression of relevant genes involved in terpene synthesis, which in turn probed the molecular mechanisms of the biosynthetic pathway[36]. After reporting the whole genome sequence of D. zingiberensis, the transcriptome data of this species, which is rich in saponins, were analyzed in comparison with those of 13 saponin-containing species of the Dioscorea spp. Specific gene expression patterns of biosynthetic pathway genes were found to promote differential evolution of the saponin biosynthesis pathway in D. zingiberensis[15]. The yam domestication process has resulted in an increasing percentage of starch, and significant differences in the expression levels of related synthetic genes between the two substances were also found during the study. Starch is a key component affecting the yield and nutrition of yam tubers. Zhang et al.'s transcriptome analysis of D. polystachya species at various stages after sowing concluded that 135 d after sowing was the critical period for starch accumulation, and also verified the conclusion of the previous study on tuber dilation[37]. Flavonoids mainly affect color change in yam tubers, but the mechanism of color change is not fully understood so far. Comparative transcriptome analysis of white-meat and purple-meat varieties of D. alata species revealed significant differences in the expression of a large number of genes[38]. By identifying functional genes in the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway (FBP) of this species, it was found that genes encoding enzymes related to this pathway were significantly up-regulated in purple flesh varieties (Fig. 3b). D. cirrhosa, which is used as a natural dye and medicinal plant because of its reddish-brown tubers, was analyzed and 67 candidate genes related to the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway were identified[39].

The storage of yam tubers is crucial, but relatively few studies of this kind have been conducted, and current research is directed towards the preservation of microtubers before sowing and severe post-harvest hardening (PHH). D. bulbifera field plantings usually use microtubers as propagation material, but they are highly susceptible to harboring pathogens that cause softening and rotting. Placement at low temperatures prolongs preservation, so transcriptome data of D. bulbifera at 4 °C were explored[39]. Look for preservation mechanisms and mining of related genes yielded a large amount of information related to microtubers preserved in vitro at low temperatures[40]. In response to the issue of hardening, which is defined as beginning within 24 h of harvest and becoming progressively unfit for human consumption, D. dumetorum is particularly pronounced[41]. In the first transcriptomic study of D. dumetorum transcriptomic data from three sclerotized and one non-sclerotized germplasm were analyzed to identify genes involved in the PHH phenomenon[41]. The study discovered that PHH involve the combined action of several genes, encoding cell wall polysaccharide components were significantly up-regulated, suggesting that they directly contribute to tuber hardening (Fig. 3c).

Yam is an important cash crop in China, but it is susceptible to diseases caused by fungal infections, leading to a decline in quality and output of yam, so it is necessary to characterize its disease resistance. Gray mold is a common disease of yam that is sensitive to defensive hormones such as ethylene (ET), and yam-related transcription factors (TF) are involved in their synthesis and breakdown[42]. To explore the differences in hormone accumulation and gene expression patterns between resistant and susceptible yam varieties, Minghuai 3 (MH3), a highly susceptible variety to Bortrytis cinerea, and Minghuai 1 (MH1), a highly resistant variety, was selected to perform a comparative transcriptome analysis, which provided a basis for unraveling the regulatory mechanisms of the different varieties to the pathogen. Comparison of gene expression after inoculation of both varieties revealed that genes involved in ET signaling plays a key role in the antimicrobial mechanism. Further validation for this result was done by analyzing the gene expression of MH1 and MH3 after vinblastine treatment, and it was found that vinblastine treatment significantly increased the resistance of highly susceptible varieties to the pathogen.

-

Many types of information cannot be gleaned from the study of genes alone; the end products of genes are inherently more complex and closer to function than the genes themselves. Therefore, only through the study of proteins can we determine the functions of proteins that are profoundly affected by post-translational modifications[43]. The study of proteomics is also becoming more and more important, using techniques that are becoming more and more accurate in analyzing proteins as technology develops. There are fewer proteomic studies on yam, and the main research methods are gel-based mass spectrometry and mass spectrometry-based isotope tagging for relative and absolute quantification (iTRAQ). The main focus is on tuber research, such as the growth and development of tubers, and their chemical composition analysis.

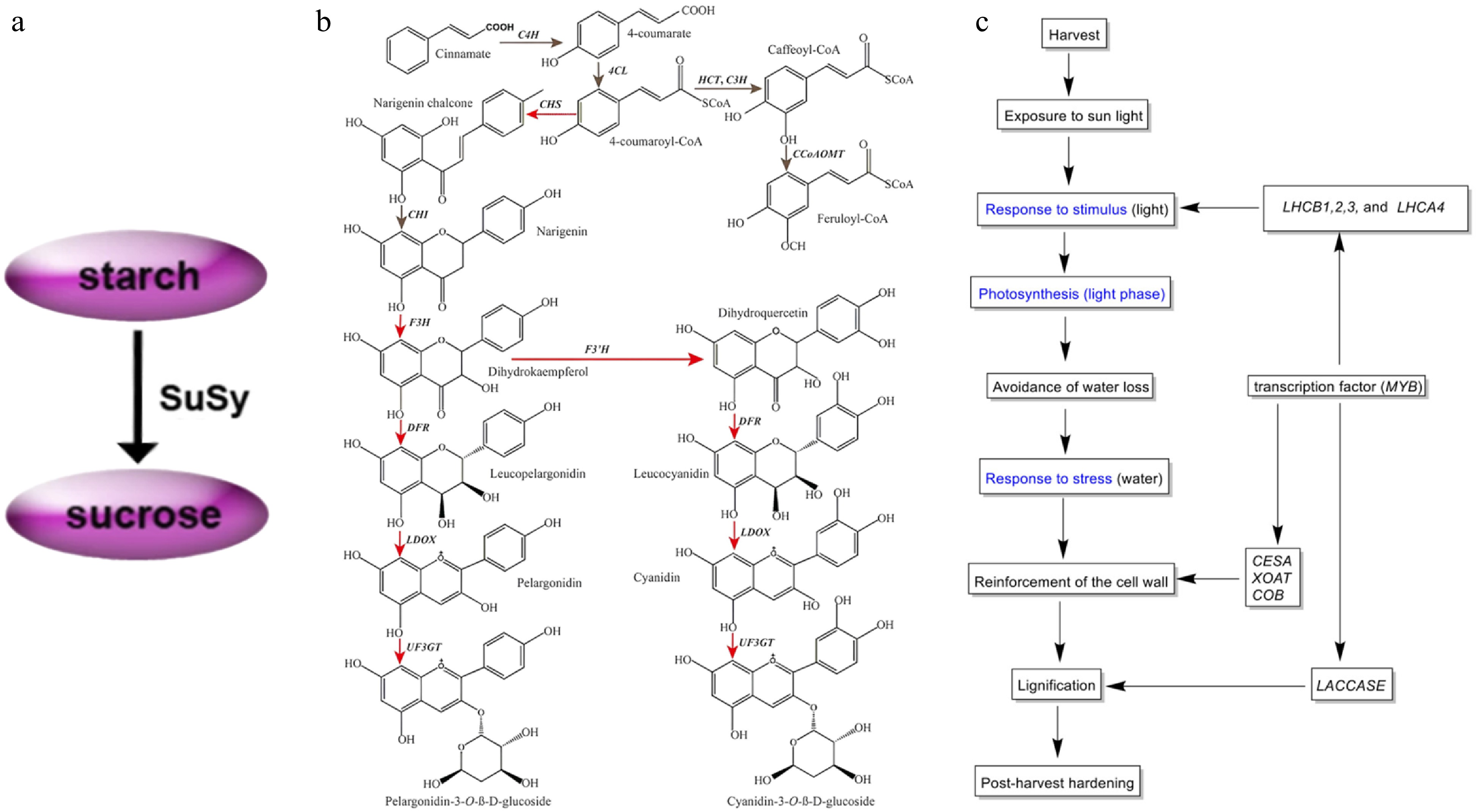

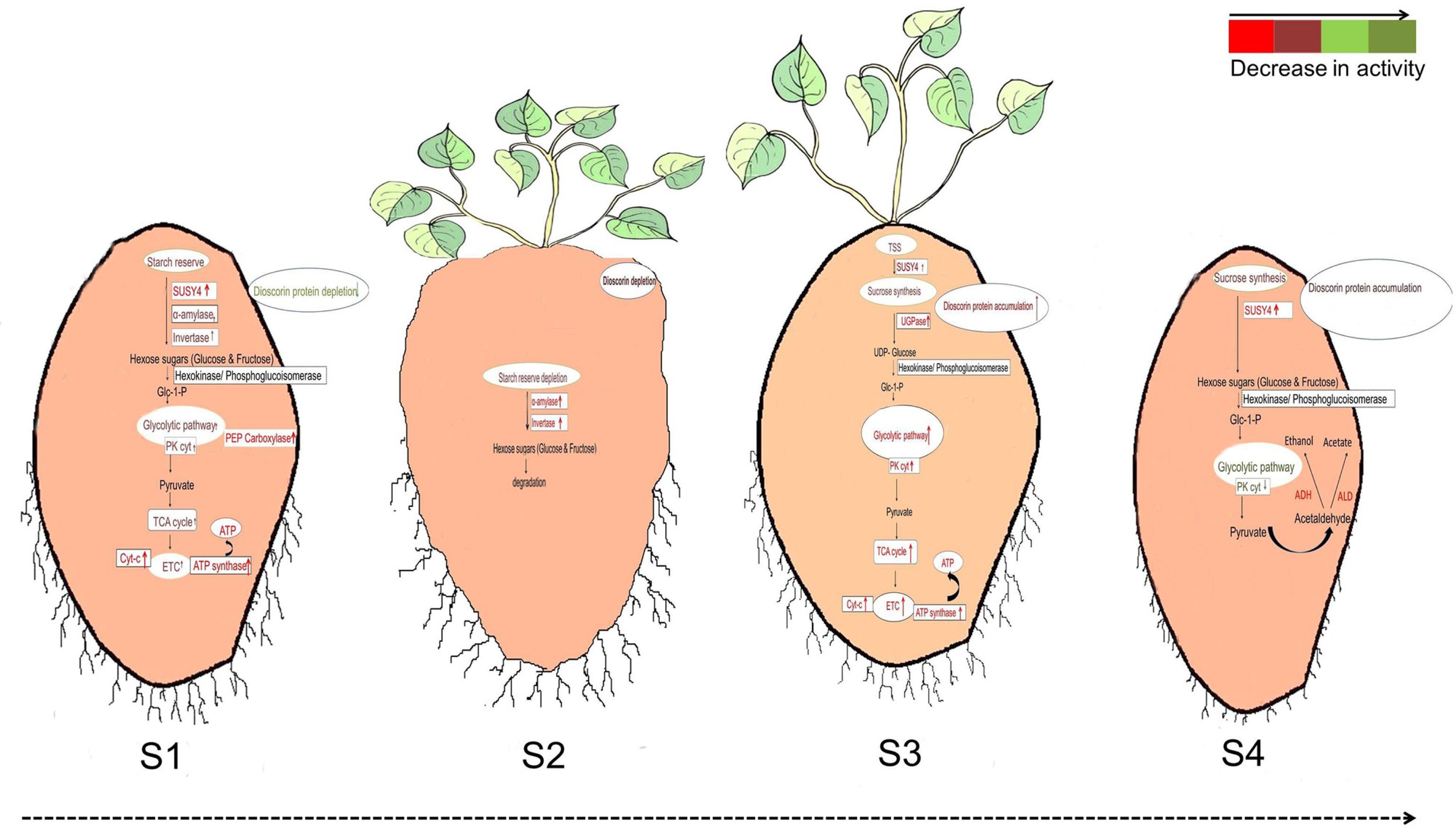

Studies on the growth and development of yam tubers at the gene level have been described in detail, but studies on the protein level have been less involved. In 2021, Sharma & Deswal reported a comprehensive tuber protein dataset for D. alata and analyzed the differences in protein levels at different growth stages[44]. Stage-specific gel-free proteomic analyses were performed for four different morphological stages: tuber sprouting (S1), degraded tuber (S2), new tuber formation (S3) and tuber maturation (S4). This research provided growth-specific markers for S1 and S3, revealing differences in protein expression at each developmental stage (Fig. 4). When people handle yam tubers, the sap always causes itching leading to allergy when it comes in contact with the skin unavoidably, so the study of the chemical composition of yam needs to be paid attention to. Mass spectrometry (MS) and protein qualitative histology analysis of yam proteins and each fraction of proteins after isolation[45]. Yam proteins were isolated and purified and found to have itchogenic properties in some fractions, which were further analyzed, and CCP2 was preliminarily hypothesized to be the itchogenic active ingredient. Fresh-cut yam is a good solution for juice allergy problems, but it tends to turn yellow during processing and storage, which affects product quality[46]. Combined with transcriptomics studies, the mechanism of yellowing in fresh-cut yam was elucidated and the cause of yellowing was explained.

Figure 4.

Differences in the regulation of glycolysis during (S1) tuber sprouting, (S2) degraded tuber, (S3) new tuber formation and (S4) tuber maturation[44].

-

Metabolomics is characterized by end effect and amplification compared to upstream proteomics and genomics, and metabolomics can provide a direct mapping of target metabolites[47]. Therefore, to further explore the abundance of nutritional and functional components, it is necessary to discover the metabolic profile of yam tubers from different species. As yet, the corresponding metabolite profiles or databases of six species have been constructed, which are of great significance to the breeding aspect of yams[47,48] (Table 2). The metabolomic data of yam leaves were provided in the construction of the crop metabolic database, which further improved the metabolic database of yam[49,50]. Furthermore, many traits of interest such as tuber growth and development maybe directly related to metabolite composition, and therefore genomics and metabolomics have been studied more in combination.

Table 2. List of mapped Dioscorea species metabolites.

Species Metabolites number Germplasm number D. rotundata 99−116 10 D. cayennensis 96−103 4 D. dumetorum 111−130 25 D. alata 104−114 5 D. bulbifera 107−117 5 D. polystachya 431 8 Transcriptomic data suggest that yam microtuber formation is adjusted by a variety of hormones[31]. Endogenous levels of ABA was measured at different stages and found that it has a positive role in regulating microtuber formation. Metabolite assays targeting the tuber development process revealed that 400 metabolites accumulated during development[7]. Bulbs have the ability to reproduce as well as tubers, and according to ancient medical records, the clinical health effects of bulbs are superior to those of yam tubers[51]. D. polystachya species was used as a material, and its tubers and bulbs were subjected to boiling treatment and air-drying control, respectively, to compare and analyze the difference in metabolites between them, and it was found that yam bulbs had more nutrients than tubers. As a result, the mechanism of growth and development of yam bulbs is also very important. The metabolites of bulb during growth and development were analyzed, the regulation of growth hormones, CKs, ABA, and sucrose were detected to lead to bulb initiation and growth, with localized production of growth hormones being necessary to trigger the transient of formation.

Genomic analysis revealed that the genome of Dioscorea spp. contains many genes encoding secondary metabolites. Thus has the potential to synthesize many secondary metabolites, including important compounds such as diosgenin elements and flavonoid phytohormones. Identification of changes in the saponin content of saponin-rich D. zingiberensis validates the hypothesis of a saponin biosynthesis pathway obtained by transcriptomics[15]. Combination with transcriptome analysis also revealed that proanthocyanidins (PAs), a downstream metabolite of the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway maybe a key metabolite in tuber color formation, and a mechanism by which flavonoids affect tuber color was discovered[39]. All metabolites in D. dumetorum contain saponins, alkaloids, and flavonoids and the high content of saponins serves as its chemical taxonomic marker[52]. To study the difference of phenolic and antioxidant potential among six species of Indian yam, the contents of flavonoids and other substances were identified[53]. Targeting saponins and catechins in D. alata metabolites that affect tuber quality provide a basis for breeding hybrids with low saponin and catechin content[54].

-

Combining current research hotspots of scholars both domestically and internationally and addressing the gaps in Dioscorea genomics studies, future work in the field needs to be envisioned as follows:

Enhance whole-genome sequencing and evolutionary research

-

Expanding whole-genome sequencing to other Dioscorea species is an important direction for future genomic research in the genus. Utilizing comparative genomics to integrate interactions between individuals and populations within the genus can help identify key genes and genetic pathways in these interactions, elucidating the adaptive evolutionary mechanisms and genetic mechanisms. Additionally, research in Dioscorea genomics should also focus on genetic diversity, taxonomic identification, and stress responses such as DNA methylation.

Improve transcriptome data and broaden studies on other tissues

-

More high-quality transcriptome will be constructed with reference to other tissues, in addition to the common yam, inter-tissue transcriptome differences in other Dioscorea species have yet to be carried out. At the same time, RNAs with mechanisms that regulate growth and development, tissue specificity and flowering need to be studied more extensively.

Enhance the development and application of proteomics

-

The development of Dioscorea proteomics has been limited, with fewer techniques used, targeting fewer species and scientific issues. Therefore, the application of the latest proteomic technologies in Dioscorea research need to be expanded to more species and scientific questions.

Strengthen research on growth, development, and tissue metabolic mechanisms

-

Multiple Dioscorea species contain a variety of important secondary metabolites. Currently, constructing metabolite maps or establishing metabolite databases focus on a limited number of species, so exploring the differences in metabolites among different species is crucial. Additionally, scientific issues explored at the metabolic level should be broader, moving beyond just tuber tissues to consider others.

Expand the scope of problem solving by multi-omics technology

-

The research aspect is not only limited to the study of yam itself, but with the updating of sequencing technology and the accumulation of histological data, it is possible to overcome the difficulties encountered in other research, such as the extraction of special components of yam.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and management: Dou D, Liu J; writing the manuscript: Chen Y, Tariq H, Shen D, Liu J, Dou D. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

This study was supported by grants from the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-21), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32270208 and 32230089) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (KYCXJC2023001 and KYQN2023039).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2024 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Chen Y, Tariq H, Shen D, Liu J, Dou D. 2024. Omics technologies accelerating research progress in yams. Vegetable Research 4: e014 doi: 10.48130/vegres-0024-0014

Omics technologies accelerating research progress in yams

- Received: 21 March 2024

- Accepted: 24 April 2024

- Published online: 17 May 2024

Abstract: Yams, belonging to Dioscorea species, are abundant in nutrients and bioactive compounds, contributing to their swiftly expanding share in the global market. Over the past 20 years, worldwide production of yams has seen a twofold increase. Particularly in Africa, yams are a staple food for millions, significantly contributing to food security and sustenance. The development of omics technologies provides an effective means for mining functional genes and exploring related molecular mechanisms in yams. This review summarizes the current research progress on the yam genome, plastome, transcriptome, proteome, and metabolome, to facilitate further genetic research and molecular breeding in yams.

-

Key words:

- Omics /

- Technologies /

- Research /

- Progressing /

- Yams /

- Accelebrating