-

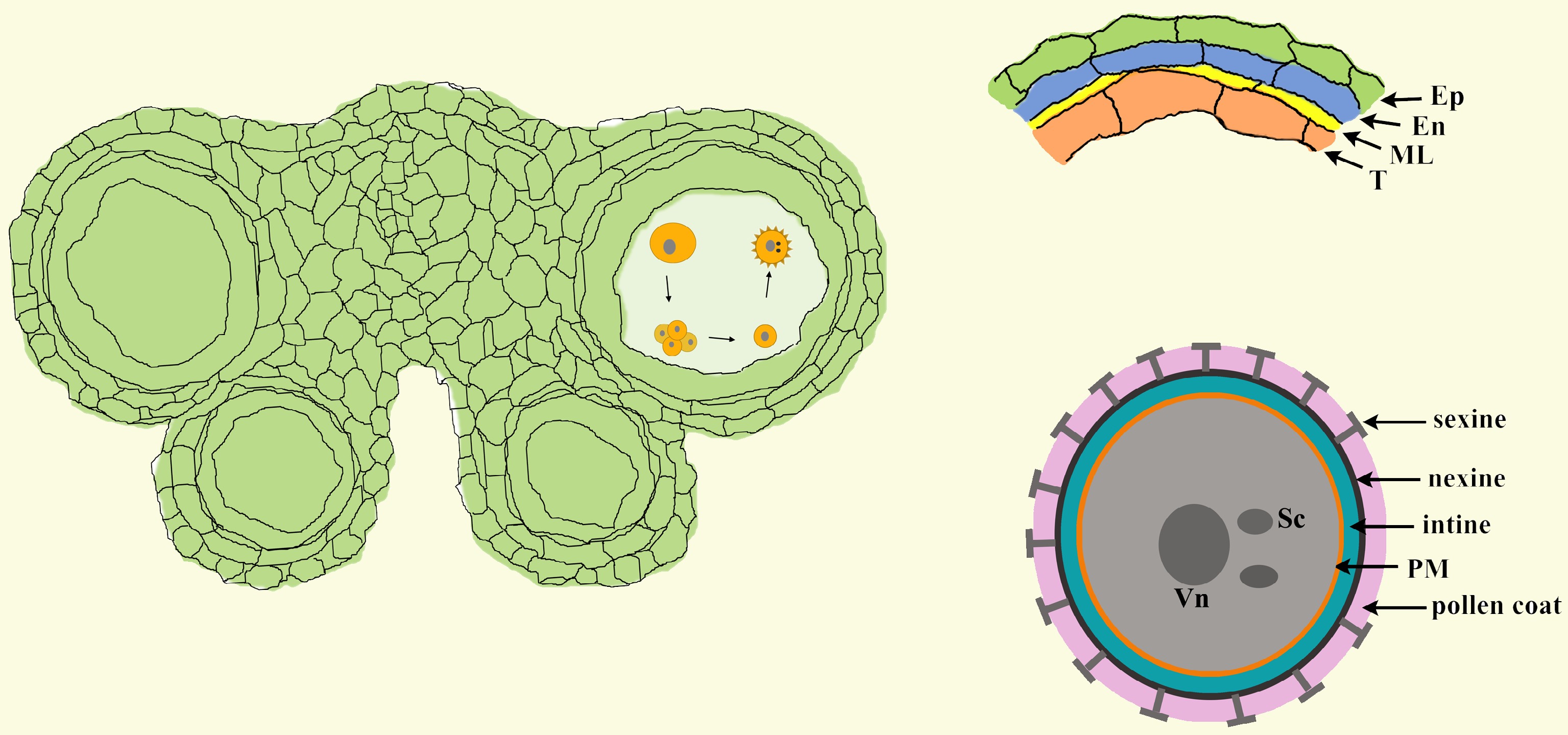

The anther is an essential organ for plant reproduction, in which mature pollen grains are produced and released. The wall of anthers consist of four layers, epidermis, endothecium, middle layer and tapetum cell, that surround the reproductive cells[1] (Fig. 1). The epidermis plays a protective role in anther development, and the endothecium is responsible for anther dehiscence to release functional pollen[2]. The tapetum is a cell layer that directly contacts microspores, and undergoes programmed cell death (PCD). It is generally accepted that tapetal cells act as 'nutrition cells' for microspore development. The middle layer exists in seed plants, but its function remains unclear. It has been proposed that the middle cell layer may partially play a similar role as the tapetum to facilitate microspore development via PCD[3]. In flowering plants, dysfunction of the tapetum is often associated with male sterility, highlighting the significance of the tapetal layer in male gametogenesis[4]. In agriculture, male-sterile plants are the necessary materials for hybrid seed production to improve the yields of crops[5].

Figure 1.

The structure of anthers and pollen. In Arabidopsis, each anther has four anther locules (pollen sacs), and the anther wall around the anther locule is composed of the epidermis, endothecium, middle layer and tapetum. Mature pollen grains are produced inside the anther locule. A pollen grain has two sperm cells in the cytoplasm of the large vegetative cell and is covered with a complex pollen wall outside of the plasma membrane. Ep, epidermis; En, endothecium; ML, middle layer; T, tapetum; Vn, vegetative nucleus; Sc, sperm cell; PM, plasma membrane.

In the anther locule, the diploid microsporocyte undergoes meiosis to form microspores that are enclosed inside a tetrad. After being released from tetrad, microspores undergo two rounds of mitosis to develop into mature pollen[6]. During these processes, the structure and composition of the cell wall undergo drastic changes (Fig. 2). The primary cell wall surrounding the microsporocyte is mainly composed of cellulose, hemicellulose and pectin[7,8]. Before meiosis, the cellulose of the primary cell wall is degraded, leaving the wall to be mainly composed of pectin. This structure is also termed the pectin wall[9,10]. At the initiation of meiosis, a layer of callose composed of β-1, 3-glucan (callose wall), is formed between the cell membrane and the pectin wall. When meiosis is completed, tetrads are formed with four haploid microspores enclosed inside the thick callose wall and the outer pectin wall[10]. At the late tetrad stage, a layer of matrix, named primexine, that is composed of polysaccharides, cellulose and proteins is deposited between the plasma membrane and the callose wall of individual microspores[11]. It is widely recognized that primexine acts as a scaffold for the formation of pollen exine. The main component of the exine layer is sporopollenin, which is an extremely biochemically resistant material[12]. After the microspore plasma membrane undulates, sporopollenin is assembled at the peak of the undulation to form probacula and is finally shaped into the complete pollen exine[13]. The exine can be further divided into the outer sexine and nexine. When the exine preliminarily forms, an intine is formed beneath the nexine[14,15]. Finally, the sculptured cavities of the sexine are then filled with tryphine, and this structure is named the pollen coat. Mature pollen grains with multiple-layered pollen walls are ready to be released from anthers[12]. Several excellent reviews that focus on the structure of the pollen wall, the biosynthesis of sporopollenin and the formation of the pollen wall have been published[16−21].

Figure 2.

The cell wall undergoes a tremendous change during pollen development. The orange quadrilaterals represent the tapetal cells, and the corresponding microspores or pollen at specific anther stages are shown under the tapetum cells. At stage 7, the four microspores are enclosed inside the callose wall and the outer pectin wall. At late stage 7, the sexine and nexine precursors start to deposit outside the membrane. During stages 9 to 10, the tapetum begins to degenerate and becomes spongy. The intine layer appears between the plasma membrane and nexine layer at stage 10. At stage 11, the tapetum evidently degenerates, and the pollen coat precursor start to fill the sculptured cavities of the sexine. At stages 12 and 13, the tapetum cell degenerates completely, and all layers of the pollen wall are established.

Tapetal cells exist in the microsporangium or anther of all land plants[22]. Ectopic expression of RNase in the tapetum cell leads to male sterility, implying a close connection between the tapetum and pollen formation[23]. As the 'nutrition cells' for the growth of microspores, tapetal cells have evolved several properties with high transcriptional and translational activity. In Arabidopsis, the tapetum layer turns into polar secretory cells at the late development stage. Each tapetal cell contains two nuclei, and its cytoplasm is condensed and packed with abundant plastids, mitochondria and vesicular transport systems. During anther development, the tapetum cell undergoes PCD to provide enzymes and materials for pollen formation[24−28]. The contribution of the tapetum to pollen development based on cytological observation has been extensively studied. In recent years, many genes essential for anther development have been discovered in male-sterile plants. Many of these genes are expressed in the tapetum and are essential for pollen formation. Here, we combine the cytological and molecular results of recent progresses in this field to propose a cascade contribution of the tapetum to pollen development, including nutrition supply, microspore release, exine deposition, pollen coat formation, and we also introduce the tapetum function for providing small RNAs to regulate genic methylation in germline cells.

-

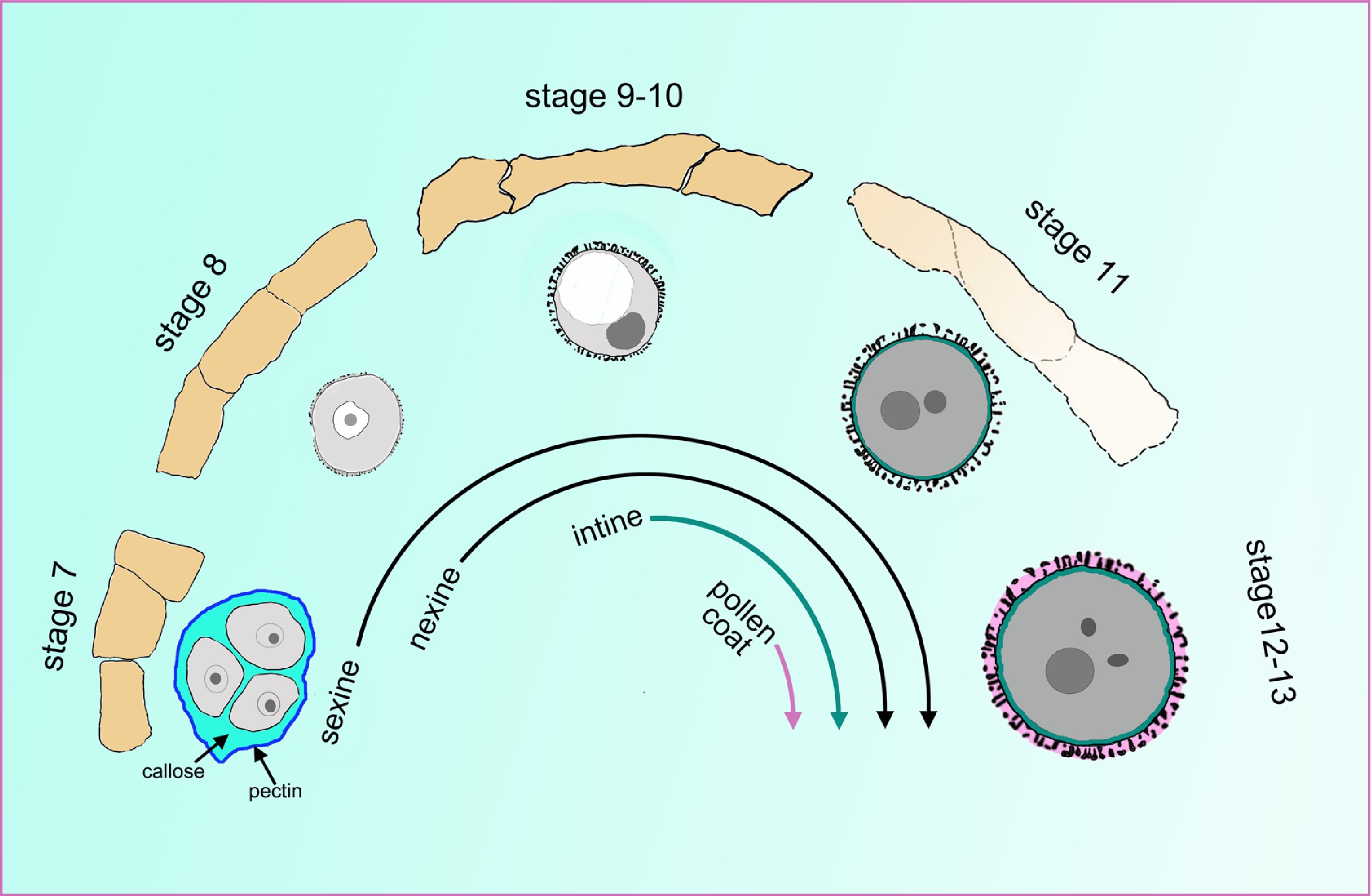

In Arabidopsis, five transcription factors specifically expressed in the tapetum have been proven to be critical for pollen formation. DYSFUNCTIONAL TAPETUM 1 (DYT1) and ABORTED MICROSPORE (AMS) are basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) family members[29−31]. DEFECTIVE IN TAPETAL DEVELOPMENT AND FUNCTION 1 (TDF1) and MS188/MYB103/MYB80 encode R2R3 MYB transcription factors[32]. MALE STERILITY 1 (MS1) is a plant homeodomain (PHD)-finger transcription factor[33,34]. In mutants of dyt1, tdf1 and ams, their hypertrophic tapetal cells occupy the locule and crush the microspores[32]. In ms188 and ms1, the tapetal cells are defective, as they have a turgid shape. However, anther locules can form, suggesting their essential roles in late tapetal development[33−37]. Based on gene expression, cytological and genetic analyses, a genetic pathway (DYT1-TDF1-AMS- MS188-MS1) was identified[38]. In addition to these five key transcription factors, several other transcription factors are redundantly involved in the development of the tapetum. Two GAMYB-like genes, MYB33 and MYB65, influence the development of the tapetum and pollen. In the myb33 myb65 mutant, the tapetal cells become hypertrophic, leading to pollen abortion. This phenotype is similar to that of tdf1. Under low temperature or high light, the fertility of myb33 myb65 increases, implying that MYB33 and MYB65 play an additional role in modulating fertility at decreased temperatures[39]. Additionally, three bHLH genes in Arabidopsis, bHLH010, bHLH089 and bHLH091 are redundantly required for early tapetum development. The bhlh010 and bhlh089 single mutants display normal fertility. However, the tapetal cells of the bhlh triple mutant were abnormally expanded and irregularly organized, which is similar to the phenotype in dyt1. These three bHLH proteins interact with DYT1 and may influence the function of DYT1. In the bhlh triple mutant, the expression of MYB103, MS1 and MYB99 was reduced. This implies that these three bHLH transcription factors redundantly regulated tapetum development by interacting with DYT1 and affecting the expression of many target genes, such as MYB103, MS1 and MYB99[40,41].

In the past 10 years, molecular and biochemical evidence has further shown that the five genes of the genetic pathway are sequentially activated during tapetum development. DYT1 directly binds to the promoter of TDF1 to activate its transcription. The expression of TDF1 is driven by the DYT1 promoter and could rescue the transcription of AMS, MS188, MS1 and a series of pollen wall-related genes in the dyt1 background. This indicates that DYT1 regulates pollen wall formation via TDF1[42]. TDF1 directly regulates the expression of AMS[43] which further regulates the expression of MYB80/MS188[44,45]. Finally, MYB80/MS188 regulates the expression of MS1[46] (Fig. 3). Based on this genetic pathway, several feed-forward loops are formed to facilitate the expression of downstream targets (Fig. 3). TDF1 interacts with AMS to activate its regulation of downstream gene expression[43,44]. In addition, AMS and MS188 form a complex and facilitate the expression of sporopollenin synthesis genes[47,48]. These transcription factors, together with feed-forward loops, form a regulatory network that rapidly regulates tapetum development and pollen formation. The detailed downstream factors of these transcription factors are reviewed and summarized in the following sections (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Gene regulatory network in the tapetum of Arabidopsis and rice. Lines terminating in arrows represent positive regulation, lines with semicircle ends indicate interaction. Orange ovals and grey ovals mark the key transcription factors in Arabidopsis and rice respectively. In Arabidopsis, DYT1-TDF1-AMS are responsible for early tapetum development. AMS regulates nexine and sexine formation via TEK and MS188, respectively. MS1 is responsible for pollen coat formation. Abbreviations: TEK, transposable element silencing via AT-hook; BES1, BRI1 EMS SUPPRESSOR 1; UDT1, UNDEVELOPED TAPETUM 1; TDR, TAPETUM DEGENERATION RETARDATION; PTC1, PERSISTANT TAPETAL CELL 1.

Table 1. The summary of the key genes and their functions during anther or pollen development.

Name ID Protein Function Reference DYT1 AT4G21330 bHLH transcription factor Early tapetum development [30] TDF1 AT3G28470 MYB transcription factor Early tapetum development [32] AMS AT2G16910 bHLH transcription factor Early tapetum development [29,31] MS188/MYB80/MYB103 AT5G56110 MYB transcription factor Tapetum PCD, microspore release, exine formation [24,35,47] MS1 AT5G22260 PHD-finger transcription factor Tapetum PCD, exine and pollen coat formation [33,34] OsUDT1 Os07g0549600 bHLH transcription factor DYT1 ortholog; early tapetum development [49] OsTDF1 Os03g18480 MYB transcription factor TDF1 ortholog; early tapetum development [53] OsTDR Os02g0120500 bHLH transcription factor AMS ortholog; tapetum development [50,54] OsMS188/OsMYB80 Os04g39470 MYB transcription factor MS188 ortholog; tapetum PCD, exine formation [51,55,56] OsPTC1/OsMS1 Os09g0449000 PHD-finger transcriptional factor MS1 ortholog; tapetum PCD, exine formation [50,52,54] ZmMs32 GRMZM2G163233 bHLH transcription factor DYT1 ortholog; tapetum development [21,57,62] ZmMs9 GRMZM2G308034 MYB transcription factor TDF1 ortholog; tapetum development [57,61] ZmbHLH51 Zm00001d053895 bHLH transcription factor AMS ortholog; tapetum development [57] ZmMYB84 Zm00001d025664 MYB transcription factor MS188 ortholog; tapetum development [57] ZmMs7 GRMZM5G890224 PHD-finger transcriptional factor MS1 ortholog; tapetum development [57−59] MYB33 AT5G06100 GAMYB transcription factor Tapetum and pollen development [39] MYB65 AT3G11440 GAMYB transcription factor Tapetum and pollen development [39] bHLH010 AT2G31220 bHLH transcription factor bHLH010, bHLH089 and bHLH091 redundantly required for tapetum and pollen development [40] bHLH089 AT1G06170 bHLH transcription factor [40] bHLH091 AT2G31210 bHLH transcription factor [40] EAT1/DTD1/bHLH141 Os04g0599300 bHLH transcription factor Tapetum PCD [63,64] TIP2/bHLH142 Os01g0293100 bHLH transcription factor Tapetum PCD [65,66] MGT5 AT4G28580 Transmembrane magnesium transporter Transport Mg from tapetum to anther locule [91] QRT3 AT4G20050 polygalacturonase Pectin dissolution [10,98] A6 AT4G14080 β-1,3-glucanase Callose dissolution [107,110] UPEX1/KNS4/RES3 AT1G33430 Arabinogalactan β-(1,3)-galactosyltransferase Influence the secretion of A6 from tapetum [110] ACOS5 AT1G62940 Fatty acyl-CoA synthetase Sporopollenin synthesis [112] CYP703A2 At1G01280 Hemethiolate monooxygenase (P450) Sporopollenin synthesis [47,113] CYP704B1 AT1G69500 Hemethiolate monooxygenase (P450) Sporopollenin synthesis [114] PKSA AT1G02050 Acyltransferase Sporopollenin synthesis [116,118] PKSB AT4G34850 Acyltransferase Sporopollenin synthesis [116,118] TKPR1 AT4G35420 Tetraketide alpha-pyrone reductase Sporopollenin synthesis [117] TKPR2 AT1G68540 Tetraketide alpha-pyrone reductase Sporopollenin synthesis [117] MS2 AT3G11980 Fatty acid reductase Sporopollenin synthesis [115,116] ABCG26 AT3G13220 ATP binding cassette transporter Sporopollenin transportation [120,121] ABCG15 AT3G21090 ATP binding cassette transporter Sporopollenin transportation [123] TEK AT2G42940 AT-hook nuclear localized (AHL) protein Nexine formation [44,103] OsOSC12 Os08g0223900 Bicyclic triterpene poaceatapetol synthase Pollen coat formation [139] GRP17 AT5G07530 Glycine-rich protein Pollen coat protein [140,141] EXL4 AT1G75910 Lipase protein Pollen coat protein [140,142] EXL6 AT1G75930 Lipase protein Pollen coat protein [140] CER1 AT1G02205 Decarbonylases Pollen coat synthesis: very long chain alkane synthesis [152,153] CER3/FLP1/WAX2/YRE AT5G57800 Decarbonylases Pollen coat synthesis: very long chain alkane synthesis [149−151,153] KCS7 AT1G71160 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase Pollen coat synthesis: fatty acid elongation [146] KCS15 AT3G52160 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase Pollen coat synthesis: fatty acid elongation [146] KCS21 AT5G49070 3-ketoacyl-CoA synthase Pollen coat synthesis: fatty acid elongation [146] Dcl5 Zm00001eb104810 Endoribonuclease Generation of 24-nt phasiRNAs in the tapetum in maize [181] CLSY3 AT1G05490 Helicase Generation of 24-nt siRNAs in the anther in Arabidopsis [182] In rice, the homologies of the five transcription factors in the pathway have been identified[20,49−53] (Fig. 3). UNDEVELOPED TAPETUM 1 (UDT1), a bHLH transcription factor that shows high homology with DYT1, plays a major role in the differentiation of tapetal cells[49]. OsTDF1 is an orthologue of Arabidopsis TDF1, and the ostdf1 knockout mutant displays vacuolated and hypertrophic tapetal cells, which is similar to the tdf1 mutant[53]. The TAPETUM DEGENERATION RETARDATION (TDR) gene, an orthologue of AMS, has been proven to be a critical component in regulating tapetum development in rice and is important for aliphatic metabolism in pollen[50,54]. PERSISTANT TAPETAL CELL1 (PTC1)/OsMS1 is the orthologue of Arabidopsis MS1[50,52,54]. The function of OsMS188/OsMYB80 has been reported recently. The osms188/osmyb80 mutant exhibited aberrant degradation of tapetal cells, lack of sexine and microspore degeneration[55,56]. Similar to Arabidopsis, the OsUDT1-OsTDF1-OsTDR-OsMS188-PTC1 genetic pathway is present in the rice tapetum[53,56]. In maize, the homologies of AtDYT1/OsUDT1, AtTDF1/OsTDF1, AtAMS/OsTDR, AtMS188/OsMS188, and AtMS1/OsPTC1 are ZmMs32, ZmMs9, ZmbHLH51, ZmMYB84, and ZmMs7, respectively[57−62]. Mutations in all five genes all lead to male sterility[57−62]. A relatively conserved genetic pathway was also proposed in maize[57]. It seems that the genetic pathway composed of the five key transcription factors in Arabidopsis, rice, and maize is conserved, which is consistent with the conservative cytological processes in monocotyledons and dicotyledons[20].

In addition to the five conserved transcription factors, two other bHLH family members have been identified to be essential for tapetal function in rice. ETERNAL TAPETUM 1 (EAT1)/DTD1/bHLH141 positively promotes PCD in tapetal cells by directly regulating the transcription of two aspartic protease-encoding genes, OsAP25 and OsAP37[63,64]. TDR INTERACTING PROTEIN2 (TIP2)/bHLH142 regulated the expression of both TDR and EAT1. TIP2/bHLH42 interacts with TDR to form a heterodimer and regulates the expression of EAT1[65,66]. EAT1 and TIP2 share sequence similarity with bHLH010, bHLH089 and bHLH091. However, unlike the redundant roles of the three bHLH genes for tapetum development in Arabidopsis, both the tip2 and eat1 single mutants display delayed tapetal PCD. This finding indicates that they are both essential regulators of tapetal PCD in rice. In addition to delayed PCD phenotypes, the three inner layers of the anther wall of tip2 but not eat1 remained undifferentiated from stage 7 to stage 8, implying the specific function of TIP2 in the differentiation of these cells[63,65].

Plant hormones are important for plant growth. Auxin (IAA), gibberellin (GA) and brassinosteroid (BR) hormonal signals are integrated into the tapetum genetic program for anther and pollen development (Fig. 3). Auxin is involved in anther morphogenesis and pollen formation[67−69]. ARF17, an auxin response factor, is expressed in microsporocytes, microspores, tapetum, and endothecium[70−72]. In the arf17 mutant, the tapetum development is defective, and the pollen wall pattern cannot be formed[70,71]. However, the detailed relationship between ARF17 and the DYT1-TDF1-AMS-MS188-MS1 genetic pathway is unknown. In addition to its function in the tapetum, ARF17 is also involved in callose wall degradation and anther dehiscence[70,72]. BR mutants exhibited abnormal tapetal development, reduced pollen production, and an irregular pollen exine pattern[73,74]. BRI1 EMS SUPPRESSOR 1 (BES1) is a key factor in the BR signalling pathway. BES1 acts upstream of DYT1 to regulate tapetum development in Arabidopsis[73,74]. In addition to the tapetal defects discovered in the GAMYB mutant myb33 myb65 in Arabidopsis, common defects in tapetal PCD and exine formation were found in GA-deficient, GA-insensitive and gamyb mutants in rice[75]. Moreover, the application of exogenous GA rescues the male infertility caused by low temperature stress[76]. These results suggest that GA participates in the regulation of anther/pollen development. DELLA/SLR1 is the central negative regulator of GA signalling. Similar to myb33 myb65, the hypertrophy phenotype in tapetal cells is present in a DELLA loss-of-function double mutant lacking both the DELLA paralogues REPRESSOR OF ga1-3 (RGA) and GA INSENSITIVE (GAI)[77]. Recently, it was reported that rice DELLA/SLR1, is required for tapetum development[78]. In the slr1 mutant in rice, the programmed cell death of the tapetum is premature, and pollen is aborted without exine formation. As an important transcription factor, OsMS188 interacts with SLR1 to cooperatively activate the expression of sporopollenin biosynthesis genes, such as CYP703A3, DEFECTIVE POLLEN WALL (DPW), and POLYKETIDE SYNTHASE (PKS1) and the sporopollenin transport-related gene ABCG15. The activation of these genes may be responsible for subsequent pollen wall formation[78]. Thus, a GA–DELLA–OsMS188 module has been revealed to control the development of the male reproductive system.

-

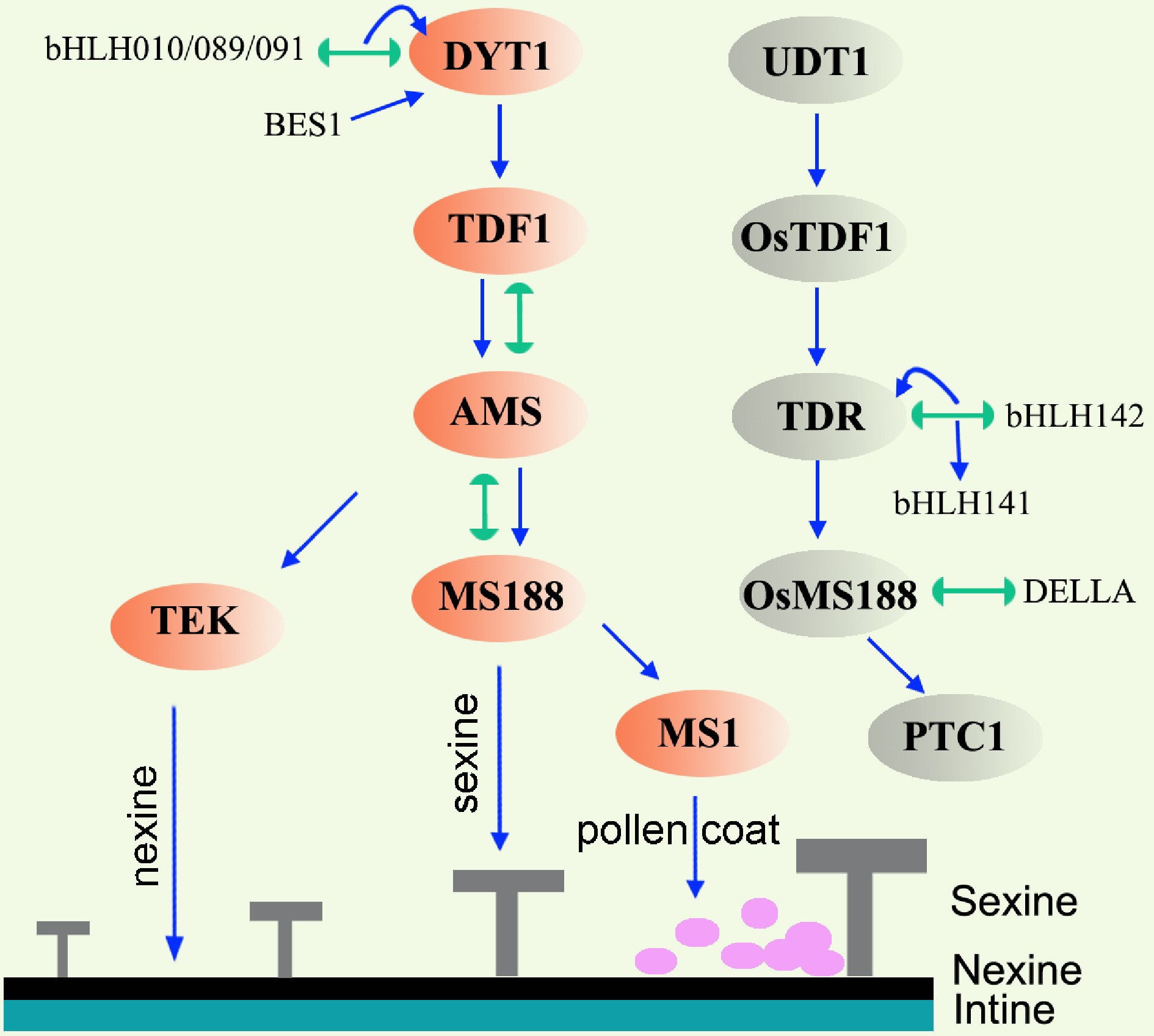

After being released from tetrads, microspores are immersed in the locule nutritive fluid whose composition fluctuates during anther development. The locular fluid contains sugars, proteins, amino acids and sporopollenin precursors during early microspore growth, and precursors for pollen coat formation during the late pollen maturation stage[79,80]. These substances in the locular fluid are secreted from the tapetum cells to meet the requirement of normal growth microspore development[80]. Extracellular invertase is responsible for sugar hydrolysis[81]. In tobacco, Nin88 encodes an extracellular invertase isoenzyme, and it is specifically expressed in tapetum and pollens. Antisense repression of Nin88 or over-expression of an invertase inhibitor under the Nin88 promoter all results in pollen abortion in tobacco[82,83]. AtcwINV2 is a homologous gene of Nin88 in Arabidopsis and it is specifically expressed in anther. Antisense repression of AtcwINV2 leads to reduced seed setting and pollen germination[84]. All these results indicated that sugars and their hydrolytic products in the anther especially in the tapetum are critical for pollen formation[82,83,85]. In rice, CARBON STARVED ANTHER (CSA) encodes a tapetum-expressed R2R3 MYB transcription factor. It regulates the transcription of MST8, a monosaccharide transporter, for sugar partitioning during anther development[86]. Magnesium is a divalent metal cation essential for living cells. In plants, the magnesium transporter (MGT) is responsible for the absorption and transport of Mg. In Arabidopsis, the magnesium transporter family contains 10 members[87,88]. MGT4, MGT5 and MGT9 are expressed in pollen and have the ability to absorb Mg from anther locule fluid for pollen formation[89,90]. Additionally, MGT5 and MGT6 are also expressed in the tapetum[91,92]. In the mgt5, mgt5+/- and mgt6+/- mutants, pollen mitosis is abnormal, and pollen intine is defective. These effects lead to pollen abortion. AMS directly regulates the expression of MGT5 to export Mg from the tapetum to the locular fluid[91] (Fig. 4). In conclusion, MGT5 plays dual roles as both a sporophytic and gametophytic gene. It not only exports Mg from the tapetum but also absorbs Mg into pollen. In the meantime, other MGTs may play essential or redundant roles in the tapetum or pollen to provide sufficient amounts of Mg for pollen growth.

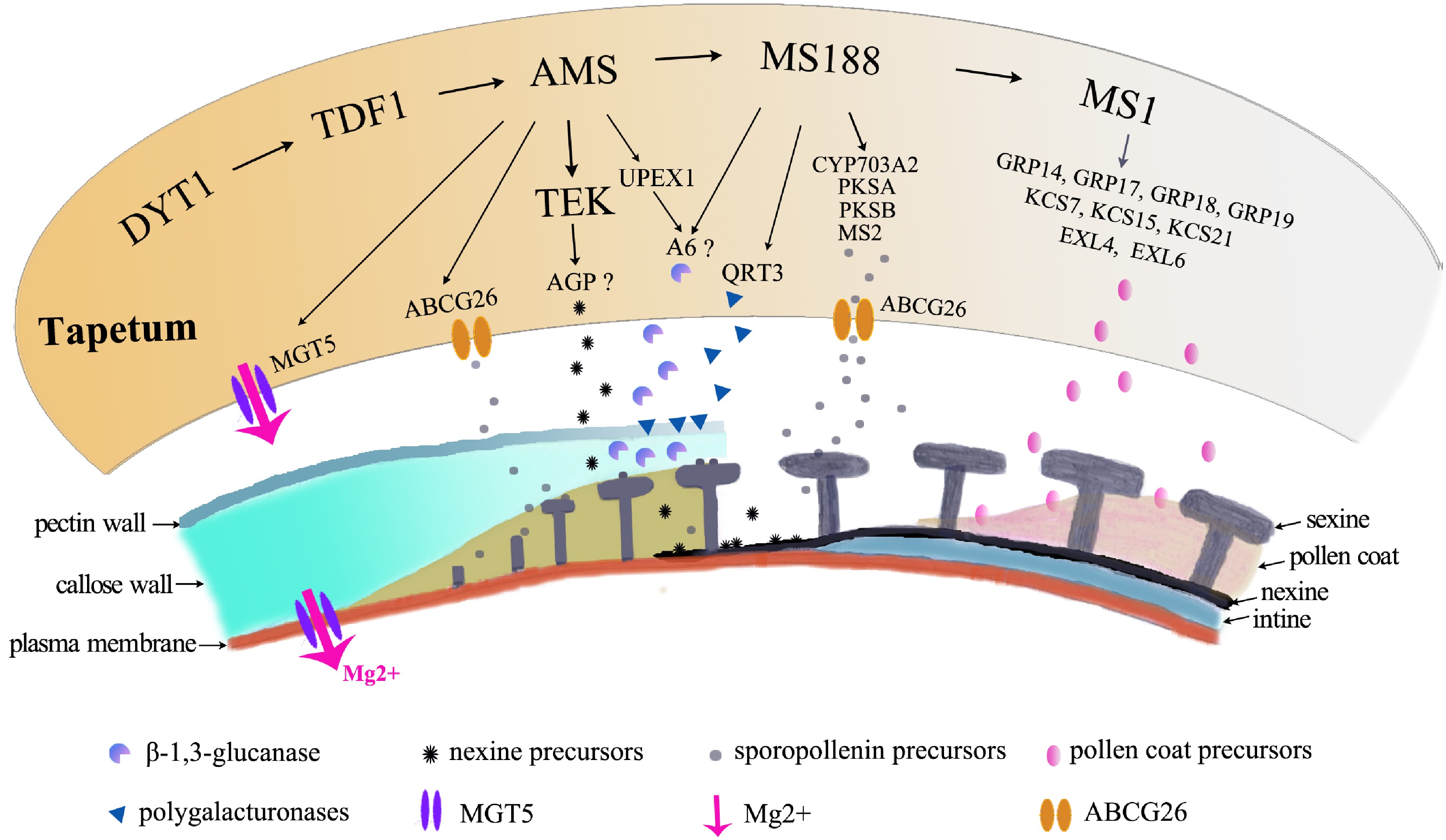

Figure 4.

Molecular pathways in tapetum contribution to pollen formation. The orange irregular shape represents the tapetal cell. The pathway regulates a large number of genes for pollen growth, which are shown below the tapetal cell, to provide Mg for pollen growth, to secrete enzymes for degradation of the pectin wall, for the callose wall to release microspores, to provide precursors of nexine and sexine, and to provide materials for pollen coat formation.

-

In addition to its nutritive function, the tapetum is also responsible for tetrad wall degeneration. The wall of the tetrad is composed of a thin pectin wall and a thick callose wall. The timely degradation of the tetrad wall ensures the release of the individual microspores into the anther locule for further maturation. The pectin wall consists of homogalacturonan, rhamnogalacturonan I and rhamnogalacturonan II. The degradation of pectin requires pectin methylesterases (PMEs) and polygalacturonases (PGs)[93−95]. Failure to degrade the pectin layer following meiosis results in the formation of tetrahedral clusters of four pollen grains. This phenotype was observed in the quartet (qrt) mutants in Arabidopsis[10,96,97]. Currently, three QRT genes have been cloned. QRT1 encodes a PME, while QRT2 and QRT3 encode PGs[98−100]. Pectin is first demethylated by QRT1 and then degraded by QRT2 and QRT3 to loosen and degrade the pectin wall. All these QRTs are expressed in tapetal cells and are secreted into the locule. MS188 directly regulates QRT3 expression[10](Fig. 4). Premature expression of QRT3 in the tapetum using the A9 promoter leads to irregular exine formation, indicating that the timely degradation of the pectin wall is important for pollen wall formation[10].

The callose wall is mainly composed of β-1,3-glucan. A decrease or loss of callose synthesis leads to a defective pollen wall pattern, indicating that the callose layer is essential for sporopollenin deposition[35,70,101−103]. β-1,3-Glucanase (callase) is secreted from the tapetum cells for the degradation of the callose layer[104−106]. In Arabidopsis and Brassica napus, anther-specific protein 6 (A6) is considered to be a β-1,3-glucanase that digests the callose wall[107]. However, in the a6 mutant, the callose wall is degraded normally, implying that other genes encoding β-1,3-glucanases are also involved in callose wall degradation. A6 is specifically expressed in the tapetum and has a sharp peak in activity immediately before microspore release. In the ms188 mutant, the expression of A6 is decreased and the degradation of callose is delayed[35]. In the ams mutant, both the accumulation and dissolution of callose are abnormal, and the expression of A6 is also decreased. AMS and MS188 may determine callose degradation by regulating the expression of A6[35,108] (Fig. 4). UNEVEN PATTERN OF EXINE1 (UPEX1)/KAONASHI (KNS4)/ RESTORER OF REVERSIBLE MALE STERILE 3 (RES3) encodes a glycosyltransferase that is directly regulated by AMS in the tapetum[109−111]. In the res3 mutant, the secretion of A6 and other β-1,3-glucanases from the tapetum to the locule was delayed, which further affected the release of microspores from tetrads. It seems that AMS and MS188 regulate A6 and its family members during callose wall degradation. The authors also suggested that the delayed callose degradation in the res3 mutant may be a general mechanism by which fertility can be restored in multiple sterility lines[111], implying its application prospects in hybrid breeding.

-

The outer pollen wall exine is composed of an outer sculptured sexine layer and an inner nexine layer. The major component of sexine was considered to be sporopollenin, which is composed of biopolymers of long-chain fatty acids and aromatics. The sophisticated pathway for the synthesis of long-chain fatty acids for sporopollenin monomer formation has been well documented based on genetic phenotypes and biochemical activity[17,21]. A series of enzymes, such as ACYL-CoA SYNTHETASE5 (ACOS5), CYP703A2, CYP704B1, POLYKETIDE SYNTHASE A (PKSA), PKSB, TETRAKETIDE α-PYRONE REDUCTASE1 (TKPR1), TKPR2 and MALE STERILE 2 (MS2), are involved in this biochemical pathway in the tapetum[17,21]. ACOS5 may play a role as a fatty acyl-CoA[112]. CYP703A2 and CYP704B1 are two members of the cytochrome P450 family that are involved in catalysing the hydroxylation of different long chain fatty acids[113,114]. The hydroxylated products are either converted to fatty alcohols by MS2 or catalysed by PKSA and PKSB into triketide and tetraketide α-pyrones[115,116]. Then, the tetraketide α-pyrones are believed to be reduced by TKPR1 and TKPR2 to form polyhydroxylated tetraketide[117−119]. Most of these enzymes are specifically/abundantly expressed in the tapetum cell[47,48,108] (Fig. 4). In ms188, sexine is completely absent[35]. MS188 directly regulates the transcription of these genes for the establishment of sexine[48]. AMS binds to the promoter of several important pollen wall formation genes such as CYP703A2, CYP704B1, PKSB and TKPR1[108]. Furthermore, AMS interacts with MS188. AMS and MS188 may form a feed-forward loop to facilitate the expression of sporopollenin synthesis genes for sexine formation[47,48]. The synthesized sporopollenin precursors are predicted to be transported by members of the ATP-binding cassette transporter superfamily such as ABCG26 or ABCG15, in Arabidopsis and rice, respectively[120−123] (Fig. 4). The expression of these ABCGs is also regulated by tapetal transcription factors[56,108]. Overall, both the biosynthesis and export of sporopollenin precursors are primarily regulated by MS188 in the tapetal cells.

In addition to long-chain fatty acids, phenolics were also reported to be an essential component of sporopollenin. As early as 1987, researchers detected several phenolic materials in sporopollenin[124]. However, conflicting results were obtained via different methods[125]. In 2019, Li and colleagues showed that the sporopollenin of pine is primarily composed of aliphatic-polyketide-derived polyvinyl alcohol units and 7-O-p-coumaroylated C16 aliphatic units[126]. However, in 2020, Mikhael et al., carried out high-resolution X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (HR-XPS) and showed the absence of aromaticity in the sporopollenin exine of Lycopodium clavatum[127]. Using genetic, biochemical and cell biology techniques, Xue et al., identified that in vascular plants, phenylpropanoid derivatives are another component of sporopollenin. The genes encoding enzymes of the phenylpropanoid synthesis pathway are expressed in the tapetum in Arabidopsis. NMR studies have shown that the sporopollenin composition of ferns and lycophytes is different from that of seed plants[128]. It is known that sporopollenin can absorb UV to protect pollen[129]. Xue et al. demonstrated that phenylpropanoid derivatives are essential for UV protection in pollen[128]. In conclusion, genetic evidence shows that both aliphatic units and phenypropanoid phenolics are essential components of the sporopollenin wall.

-

Nexine is a layer between the sexine and an inner intine. Usually, this cell wall is observed under transmission electronic microscopy in seed plants. As it is difficult to isolate this layer for composition analysis, the current understanding of this layer is quite obscure. In Arabidopsis, TRANSPOSABLE ELEMENT SILENCING VIA AT-hook (TEK) encodes an AT-hook nuclear localized (AHL) protein. The nexine layer is absent in the tek mutant, but sexine is normally formed, indicating that the formation of sexine is independent of the nexine layer[44] (Fig. 4). In the tapetum, AMS directly regulates MS188/MYB80 for sexine formation. TEK is strongly expressed in the tapetum at stage 7 and is also a direct target of AMS[44]. Therefore, AMS directly regulates MS188 for sexine formation and regulates TEK for nexine formation (Fig. 4). TEK was found to regulate the transcription of genes encoding arabinogalactan proteins (AGPs)[130]. However, the presence of AGPs in nexine has not yet been verified.

-

The pollen coat, which covers the surface or fills the sculptured cavities of the sexine, is responsible for pollen stigma interactions and pollen hydration and protects pollen from harsh environmental stress[13,131−136]. Recently, two pollen coat-specific staining dyes: pollen-coat-stain (PCS) 52 and PCS 184, were identified. These two pollen coat dyes together with the exine dye basic fuchsin (BF) clearly stain the pollen coat and pollen wall in vivo in angiosperms[137].

The pollen coat is composed of proteins, lipids, isoprenoids, and glycoconjugates[133,138]. In rice, OsOxidosqualene cyclases 12 (OsOSC12) encodes a bicyclic triterpene synthase and plays a role in the triterpene pathway. It is expressed in tapetal cells. Deficiency of OsOSC12 leads to a defective pollen coat and shows a humidity-sensitive genic male sterility (HGMS) phenotype. These findings imply that the tapetum-synthesized triterpene is an essential component in the pollen coat to prevent dehydration of pollen grains[139]. In Arabidopsis, pollen coat proteome analysis revealed that pollen coat proteins consist mainly of two families: lipid-binding oleosin or glycing-rich protein (GRP) and extracellular lipase (EXL)[140]. GRP17 accounts for the largest proportion of pollen coat proteins in Arabidopsis[140]. Mutations of GRP17 impair pollen hydration and the competitive ability, indicating the importance of this protein in hydration[141]. EXL4 and EXL6 were also identified in the pollen coat[140]. In the exl4 mutant, pollen hydration is slower. As a lipase, it was suggested that EXL4 may change the lipid composition to improve the ability of pollen to absorb water from the stigma[142]. Lipids are another main component of the pollen coat, and are important for pollen stigma communication and pollen hydration. Most of the detected lipids in the pollen coat are derivatives of very-long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs)[143]. A number of mutants that disturb long chain lipid synthesis, such as eceriferum 1 (cer1), cer3/faceless pollen-1 (flp-1)/wax2/yre, 3-ketoacy-CoA synthase 7 (kcs7) kcs15 kcs21, and long-chain acyl-CoA synthetases 1 (lacs1) lacs4, show pollen coat defects[143−146]. 3-Ketoacy-CoA synthase (KCS) catalyses fatty acid elongation[147,148]. CER1 and CER3/FLP1/WAX2/YRE may encode fatty acid hydroxylases and are involved in the synthesis of very long chain alkanes[149−153]. It was reported that several pollen coat proteins or lipid synthesis-related enzymes are expressed predominantly or specifically in tapetal cells[46,108,146,154,155], indicating the important role of the tapetum in providing materials for pollen coat formation. ms1 was the earliest reported male sterile mutant in Arabidopsis in 1968[156]. MS1 is a plant homeodomain (PHD)-finger transcription factor[33]. The pollen wall was defective in the ms1 mutant[157]. Recently, it has been found that MS1 regulates the transcription of several pollen coat protein genes, such as GRP14, GRP17, GRP18, GRP19, EXL4, and EXL6, and pollen coat lipid synthesis genes, such as KCS7, KCS15, and KCS21[46,108,146] (Fig 4). Interestingly, it was observed that GRP19, EXL6, KCS20, KCS21 proteins are secreted into the anther locule before tapetal degradation[46,146]. These results suggest that instead of being passively released into the anther locule after tapetal degeneration, pollen coat precursors may be prepared in advance under the regulation of MS1. MS1 is directly regulated by MS188. This indicates that following sporopollenin synthesis and sexine formation mediated by MS188, MS1 subsequently regulates the expression of pollen coat protein genes. This reveals that a regulatory cascade establishes the multiple layers of the pollen wall (Fig. 4).

The tapetum provides the major components of the pollen coat. A recent investigation showed that endothecium and developing microspores also contribute to pollen coat formation[136,158−162]. CER2 and CER2-like proteins are putative BAHD acyltransferases required for VLCFA elongation. CER2, CER2L2, and KCS6 were found to be expressed in the endothecium[162], and cer2 cer2l2 and cer6/kcs6 mutants all show severe pollen coat defects[163−167]. It seems that the tapetum first secretes pollen coat proteins and lipids into the anther locule, and after the degeneration of tapetum cells, the endothecium continues to provide pollen coat lipids on the surface of mature pollen for pollen hydration. Pollen-produced cysteine-rich pollen coat proteins are also involved in pollen stigma interactions[159,160,168−170]. POLLEN COAT PROTEIN B-class peptides (PCP-Bs) are cysteine-rich pollen coat proteins[169]. It has been recently established that pollen-born PCP-Bs bind to the ANJEA–FERONIA (ANJ–FER) receptor kinase complex, to decrease stigmatic ROS and facilitate pollen hydration[170]. This data indicates that the kinds of PCPs in the pollen coat are produced and provided from different tissues.

-

Small RNAs are important for plant development because they regulate the transcript levels of target genes and the expression of transposons. It has been previously reported that pollen-specific miRNAs exist in Arabidopsis and rice[171,172]. The transcripts of Arabidopsis MYB33/MYB65 and rice OsGAMYB/OsGAMYB-like genes are targeted by miR159[39,173]. Over-expression of miR159 in Arabidopsis and rice all leads to anther defects and results in male sterility, indicating the miR159-GAMYBs module should be strictly controlled for normal anther development[173,174]. ARF17 is a target gene of miR160. 5mARF17 transgenic plants, which avoid miR160-directed ARF17 cleavage, also showed tapetal defects. These results indicate that the fine-tuned expression of ARF17 by miR160 is critical for tapetum development[71]. More and more microRNAome in developing anthers of wild-type plants and male sterile lines in different species were obtained[175−178]. In the future, it will be informative to investigate the detailed function of these potential miRNAs during anther and pollen development.

Genome reprogramming in pollen is guided by small RNAs. In Arabidopsis pollen, transposable elements (TEs) are activated only in vegetative cells. However, TE siRNAs accumulate in pollen and sperm cells, suggesting that siRNA from the vegetative nucleus can target silencing in sperm cells[179]. In maize anthers, there are two classes of phased siRNAs: 21-nt phased siRNAs (phasiRNAs) and 24-nt phasiRNAs. The 24-nt phasiRNAs and their precursors accumulate preferentially in the tapetum and meiocytes. However, tapetal cells but not meiotic cells may be essentially required for 24-nt phasiRNA biogenesis in maize[180]. Dicer-like 5 (Dcl5) is required for the generation of 24-nt phasiRNAs in maize. In the dcl5 mutant, few or no 24-nt phasiRNAs were detected, tapetal cells were defective, and the mutant displayed temperature-sensitive male fertility. These results indicate that DcL5 and 24-nt phasiRNAs are important for normal tapetum development and male fertility and the tapetum is the source for 24-nt phasiRNA biogenesis[181]. Recently, it has been found in Arabidopsis that 24-nt siRNAs are synthesized by tapetal cells through the activity of the chromatin remodeler CLASSY 3 (CLSY3). The tapetum-derived siRNA then governs germline methylation and silences germline transposons[182]. More recently, a similar mechanism was discovered in maize. Zhou et al. reported that the 24-PHAS precursor and Dcl5 primarily accumulated in the tapetum. After synthesis, the 24-nt phasiRNAs may move from the tapetum to meiocytes and other somatic cell layers in the anther wall[183]. In conclusion, in both Arabidopsis and maize, the 24-nt siRNA required for normal anther and germline development is mainly provided from the tapetum and moves into the germline cells.

-

In recent decades, the key transcription factors regulating tapetum development have been identified. In Arabidopsis, the DYT1-TDF1-AMS-MS188-MS1 genetic pathway is not only important for tapetum development, but also provides a cascade regulation for pollen formation. First, DYT1 and TDF1 regulate early tapetum development when microsporocytes are undergoing meiosis in the anther locule. At the tetrad stage, AMS initiates nexine deposition by activating the expression of TEK and promoting sexine formation via MS188 to regulate the synthesis of sporopollenin precursors. Moreover, both AMS and MS188 play critical roles in the degradation of the pectin wall and callose to gradually release the microspores from the tetrad. Last, the downstream member in the genetic pathway, MS1, regulates the transcription of a series of pollen coat related genes for pollen coat formation. Thus, mature pollen grains with multiple-layered pollen walls are ready to be released from anthers. The genetic pathway consists of five key transcriptional factors that are relatively conserved in Arabidopsis, rice and maize. However, functions of other homologous between Arabidopsis and rice are different, such as Arabidopsis bHLH010/bHLH089/bHLH091 and rice bHLH141/bHLH142. Therefore, it is necessary to explore more factors involved in the regulation of tapetum among species, analyze their relationship associated with those key transcription factors, and establish a more comprehensive gene regulatory network for tapetum development.

In future, the coordination between tapetum development and pollen formation remains to be explored. The composition of sporopollenin still remains to be deciphered. Although nexine is a conserved pollen cell wall layer in seed plants, its chemical composition is still unclear. During anther development, the cell wall of the pollen mother cell is transited to the pollen wall. This transition is critical for pollen formation and plant fertility. The enzymes that dissolve the primary cell wall of microsporocytes and the tetrad callose layer still need to be identified. Further study of these issues in different species will help us to further characterize the relationship between anther sporophytic tissues and microspores/pollens as well as the evolution of the complicated pollen wall. In future, it is also very important to study whether mutations of the key genes essential for tapetum development can also lead to sterile phenotypes in different kinds of crops, and explore the application prospects of these male sterile materials in hybrid breeding.

This work was supported by grants from National Science Foundation of China (31970520, 31870296). We thank Dr. Jun Zhu, Dr. Yue Lou and Dr. Jing-Shi Xue from Shanghai Normal University for critical reading and revising of the manuscript. We thank Kengyu Pan, Benshun Zhu and Yu Jiang from Shanghai Normal University for revising of the manuscript.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2022 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Hainan Yazhou Bay Seed Laboratory. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Yao X, Hu W, Yang Z. 2022. The contributions of sporophytic tapetum to pollen formation. Seed Biology 1:5 doi: 10.48130/SeedBio-2022-0005

The contributions of sporophytic tapetum to pollen formation

- Received: 18 July 2022

- Accepted: 26 August 2022

- Published online: 01 October 2022

Abstract: Successful pollen formation is essential for plant reproduction. During anther development, microspore mother cells undergo meiosis to form tetrads. After being released from the tetrad, microspores develop into mature pollen. The tapetum is the innermost layer of anther somatic cells and forms a locule to provide nutrition, enzymes and pollen wall materials for microspore development. Based on the male sterile phenotype, many genes important for tapetum and pollen development have been cloned. In this review, we highlight the genetic pathway of DYT1-TDF1-AMS-MS188-MS1 which acts in tapetal development in Arabidopsis. We also compared this genetic pathway in different species such as Arabidopsis, rice and maize. Based on this pathway, we review recent findings and insights into the contribution of the tapetum to pollen formation at the molecular level. 1) Tapetum provides nutrition for microspore development. 2) Tapetum provides enzymes to dissolve pectin and callose to release microspores from tetrads. 3) Tapetum synthesizes precursors for pollen wall formation via different molecular pathways. 4) Tapetum provides precursors for pollen coat formation. 5) Tapetum provides small RNAs to regulate genic methylation in the germline cells.

-

Key words:

- tapetum /

- pollen wall /

- microspore