-

Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) is one of the most important economic crops in China, and its protected cultivation area and yield are increasing year by year[1]. However, high temperature in late spring, summer, and autumn has become one of the main factors restricting protected cucumber production in the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River of China. High temperature stress leads to the decline in photosynthetic efficiency by affecting photosynthetic electron transport and related enzyme activities[2,3]. It is found that the contents of soluble protein and proline (Pro) in cucumber seedlings with different high temperature tolerance varieties increase with the enhancement of high temperature tolerance at 28, 38, and 42 °C[4]. Furthermore, the content of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and malondialdehyde (MDA) significantly increases under high temperature, which can damage cells and destroy the stability of the cell membrane[5]. Importantly, high temperature stress will damage the fruit and lead to fruit drop during the fruiting stage[6,7]. Therefore, it is imperative to alleviate the impact of high temperature on plants. Several studies have shown that exogenous spraying of growth regulators on plants can regulate their growth and improve their stress resistance.

Polyamines (PAs) are aliphatic nitrogenous compounds with small molecular weight. In the physiological pH environment, they are generally positively charged to form polycations, and have high physiological activity[8]. Furthermore, they can covalently combine with other substances to form more stable compounds, which are not easily oxidized. PAs participate in physiological, biochemical, and molecular processes, such as resistance reaction and morphogenesis[9]. Putrescine (Put) is the core substance for the synthesis of other PAs. Exogenous application of Put increases plant stress tolerance through maintaining higher chlorophyll content and photosynthesis rate, enhancing antioxidant activity to scavenge excessive ROS, and inducing the expression of genes involved in stress response[9−11]. Put significantly increases the content of photosynthetic pigment and promotes the growth of cucumber seedlings under salt stress[12]. Short-term high temperature treatment increases the content of PAs, but long-term high temperature treatment inhibits the synthesis of endogenous PAs[13]. Exogenous application of Put increases high temperature stress tolerance through regulation of NO synthesis[14]. Furthermore, the foliar application of Put before a short-term high temperature stress improves the fruit quality of melon[15]. The role of Put in high temperature stress has been gradually revealed, but its functions in cucumber under high temperature stress are largely unknown.

Melatonin (MT) is used as a biological regulator to enhance plant stress resistance through increasing chlorophyll content, accelerating photosynthetic carbon assimilation, activating ROS scavenging system, and delaying leaf senescence[16−18]. High temperature stress induces the accumulation of MT, which regulates the activities of various downstream enzymes through a series of signal transductions to control the synthesis and decomposition of substances, resulting in improved tolerance of plants to high temperature stress[19−23]. Our previous studies showed that exogenous foliar application of 100 µmol L−1 MT significantly enhances the high temperature tolerance of tomato[10,21,22,24].

Pro is an effective osmoregulation substance, which provides sufficient free water and active substances for physiological and biochemical reactions by protecting the functional structure of biological macromolecules, resulting in improving the adaptability of plants to stress[25,26]. Pro also reduces the damage to the cell membrane caused by stress through maintaining the integrity of the membrane structure[27]. In crops, vegetables, flowers, and other plants, the content of Pro is found to reflect the stress resistance of plants to some extent[28,29]. Varieties with strong resistance to stress often accumulate more Pro[28,29]. Furthermore, the foliar application of 100 mg L-1 Pro inhibits the accumulation of H2O2 and MDA, increases water use efficiency and fruit total soluble solids in tomato under high temperature stress[30].

Potassium fulvic acid (MFA) is a kind of fulvic acid fertilizer, in which fulvic acid accounts for more than 50%. It has the characteristics of low molecular weight, easy biological absorption and utilization, strong physiological activity, and easy solubility in water[31]. It can increase the content, absorption, and utilization rate of potassium fertilizer, improve crop yield and quality, and enhance crop resistance to environmental stresses[32,33]. Foliar application of MFA significantly promotes the growth and development of heading lettuce[34]. At present, the role of MFA on plants is mainly investigated under drought stress. MFA reduces stomatal opening, promotes root development, and increases chlorophyll content and antioxidant enzyme activity, resulting in enhanced plant drought stress resistance[35−37]. Although the sole critical roles of Put, MT, Pro, and MFA have been identified in different plants, their combined functions in alleviation of high temperature stress are unclear. Here, the mixture of Put, MT, Pro, and MFA (hereafter referred to as Put mixture) with different concentrations was sprayed at different growth stages (seedling, flowering, and fruiting stage) of cucumber to investigate their roles on growth, fruit yield, and quality under high temperature stress. The results showed that the foliar application of the Put mixture promoted cucumber growth, and increased yield and quality. These effects were the most profound in the plants treated with the mixture of 8 mmol L−1 Put, 50 µmol L−1 MT, 1.5 mmol L−1 Pro, and 0.3 g L−1 MFA every 7 d, three times at the seedling stage. Therefore, our results suggested that the foliar application of the Put mixture alleviated the damage caused by high temperature stress to cucumber.

-

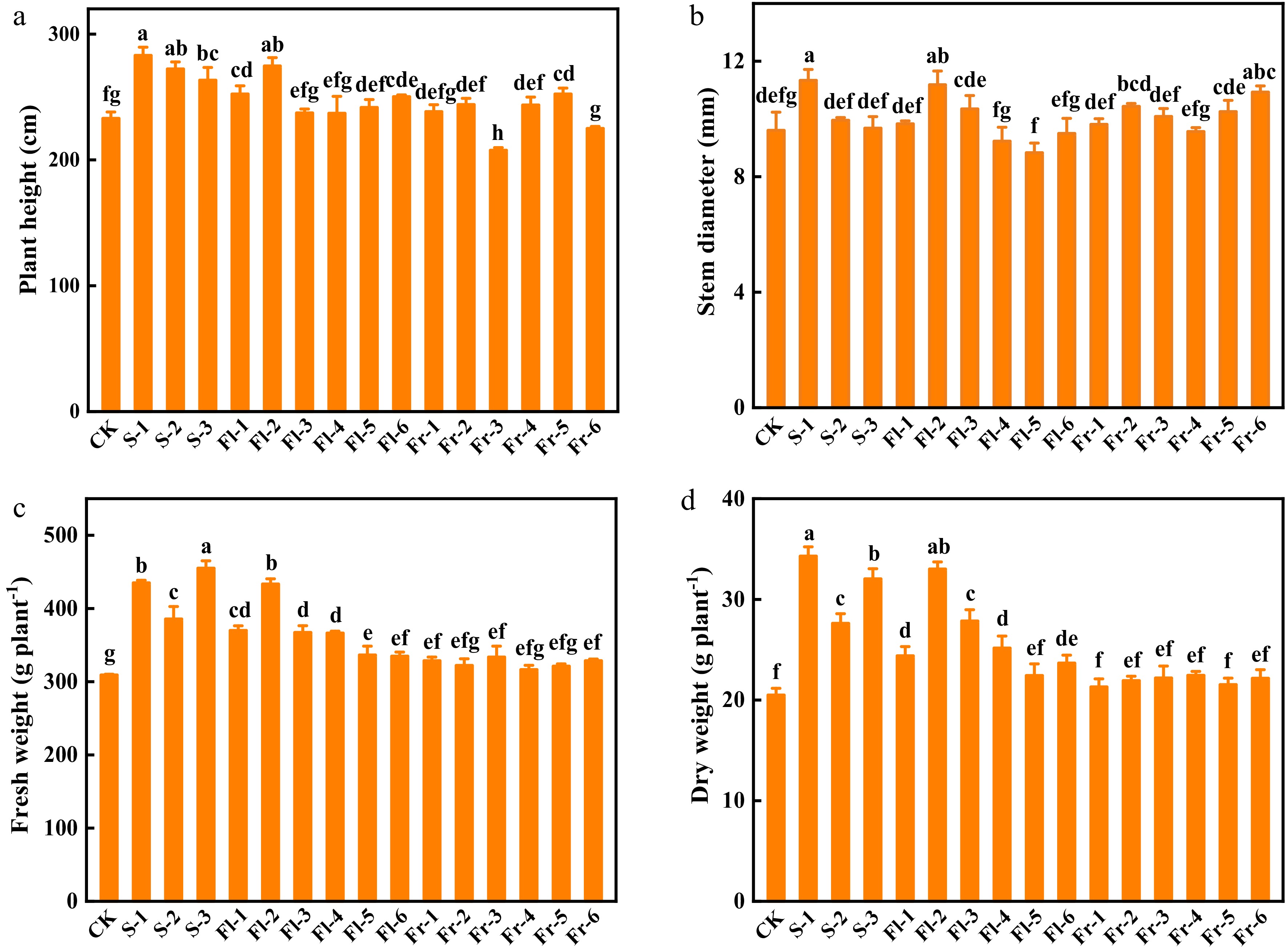

As shown in Fig. 1, the foliar application of the Put mixture promoted the growth of cucumber plants under high temperature stress, especially in the treatment applied during the seedling stage. The plant height of S-1, S-2, and S-3 treatment at the seedling stage was significantly higher than that of the control (CK), with an increase of 21.4%, 16.9%, and 13.2%, respectively (Fig. 1a). The plant height of Fl-1, Fl-2 and Fl-6 treatment during the flowering stage was significantly higher than that observed in CK (Fig. 1a). However, only the plant height of Fr-5 treatment significantly increased by 8.3% compared with CK at the fruiting stage (Fig. 1a). The stem diameter of S-1, Fl-2, and Fr-6 was 17.1%, 16.4%, and 13.8%, respectively, higher than that in CK (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, the fresh and dry weight of cucumber plants at the seedling stage treatments increased significantly compared with CK (Fig. 1c & d).

Figure 1.

Effects of the mixture of putrescine (Put), melatonin (MT), proline (Pro), and potassium fulvic acid (MFA) on the growth of cucumber plants under high temperature stress. (a) Plant height. (b) Stem diameter. (c) Fresh weight. (d) Dry weight. CK, cucumber plants without treatment with the mixture of 8 mmol L−1 Put, 50 µmol L−1 MT, 1.5 mmol L−1 Pro, and 0.3 g L−1 MFA (Put mixture, original concentration). S, Fl, and Fr indicated cucumber plants-treated with the Put mixture at seedling stage, flowering stage, and fruiting stage, respectively. 1, 2, and 3 indicated cucumber plants-treated with the original, diluted five times, and diluted ten times concentration of the Put mixture every 7 d, 3 times, respectively. 4, 5, and 6 indicated cucumber plants-treated with the original, diluted five times, and diluted ten times concentration of the Put mixture every 14 d, 3 times, respectively. Data represent as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences according to Tukey’s test at P ≤ 0.05.

Effects of Put mixture on relative electrolyte leakage, MDA, Pro, and H2O2 content of cucumber leaves

-

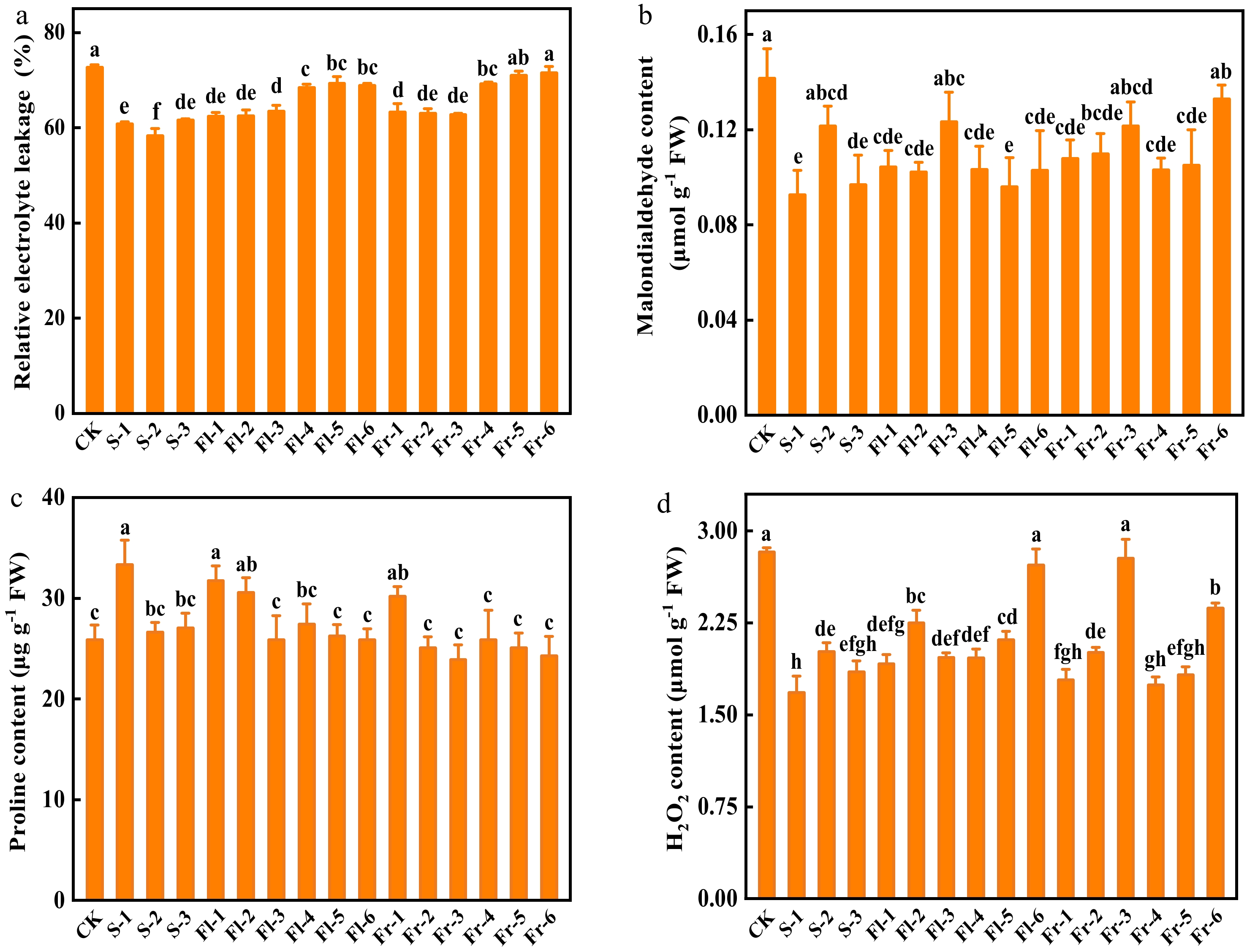

To investigate the role of the Put mixture on the cell membrane integrity of cucumber leaves, we analyzed the level of relative electrolyte leakage and MDA content of cucumber leaves after planting for 40 d. The level of relative electrolyte leakage in the Put mixture-treated plants was lower than that in CK (Fig. 2a). The level of relative electrolyte leakage in the treatment at flowering and fruiting stage every 7 d was significantly lower than those in every 14 d treatments (Fig. 2a). In addition, MDA content in all of the Put mixture-treated plants was lower than that in CK (Fig. 2b). The content of MDA in S-1 treatment was the lowest, which was 34.6% lower than that in CK (Fig. 2b). As shown in Fig. 2c, the content of Pro in cucumber leaves at the same treatment stage increased with the increase of spraying concentration. The content of Pro in S-1, Fl-1, Fl-2, and Fr-1 treatments increased by 29.1%, 22.8%, 18.2%, and 16.7%, respectively, compared with CK (Fig. 2c). There was no significant difference in the content of H2O2 between CK and Fl-6 and Fr-3 treatments, but the content of H2O2 in other treatments was significantly lower than that in CK (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2.

Effects of the mixture of putrescine (Put), melatonin (MT), proline (Pro), and potassium fulvic acid (MFA) on relative electrolyte leakage, malondialdehyde, Pro, and H2O2 content of cucumber plants under high temperature stress. (a) Relative electrolyte leakage. (b) Malondialdehyde content. (c) Pro content. (d) H2O2 content. CK, cucumber plants without treatment with the mixture of 8 mmol L−1 Put, 50 µmol L−1 MT, 1.5 mmol L−1 Pro, and 0.3 g L−1 MFA (Put mixture, original concentration). S, Fl, and Fr indicated cucumber plants-treated with the Put mixture at seedling stage, flowering stage, and fruiting stage, respectively. 1, 2, and 3 indicated cucumber plants-treated with the original, diluted five times, and diluted ten times concentration of the Put mixture every 7 d, 3 times, respectively. 4, 5, and 6 indicated cucumber plants-treated with the original, diluted five times, and diluted ten times concentration of the Put mixture every 14 d, 3 times, respectively. Data represent as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences according to Tukey’s test at P ≤ 0.05. FW, fresh weight.

Effects of Put mixture on chlorophyll content and photosynthesis under high temperature stress

-

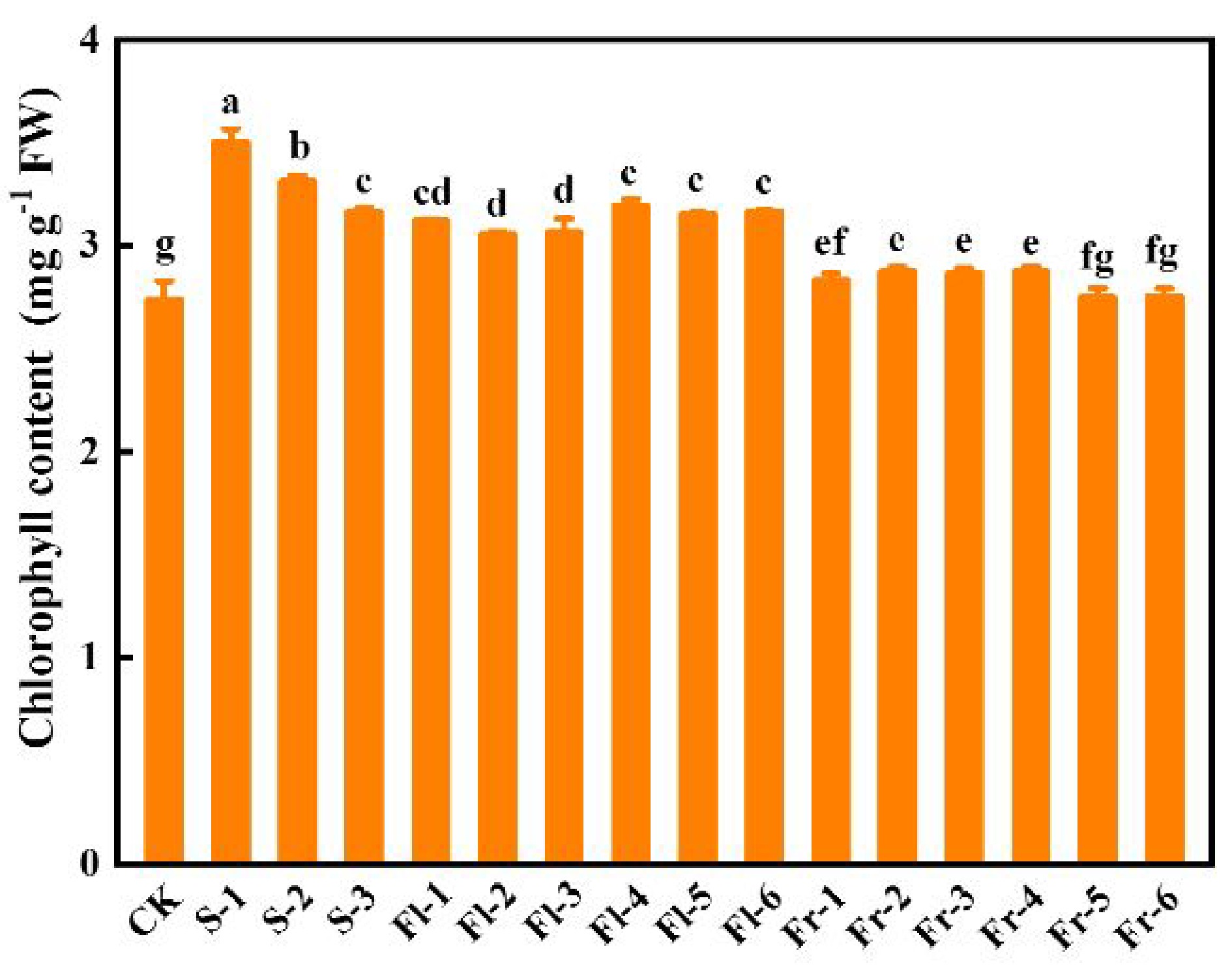

As shown in Fig. 3, spraying different concentrations of Put mixture increased the total chlorophyll content of cucumber leaves in comparison to CK. Chlorophyll content in S-1 treatment was the highest, which was 28.2% higher than that in CK (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Effects of the mixture of putrescine (Put), melatonin (MT), proline (Pro), and potassium fulvic acid (MFA) on chlorophyll content of cucumber leaves under high temperature stress. CK, cucumber plants without treatment with the mixture of 8 mmol L−1 Put, 50 µmol L−1 MT, 1.5 mmol L−1 Pro, and 0.3 g L−1 MFA (Put mixture, original concentration). S, Fl, and Fr indicated cucumber plants-treated with the Put mixture at seedling stage, flowering stage, and fruiting stage, respectively. 1, 2, and 3 indicated cucumber plants-treated with the original, diluted five times, and diluted ten times concentration of the Put mixture every 7 d, 3 times, respectively. 4, 5, and 6 indicated cucumber plants-treated with the original, diluted five times, and diluted ten times concentration of the Put mixture every 14 d, 3 times, respectively. Data represent as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences according to Tukey’s test at P ≤ 0.05. FW, fresh weight.

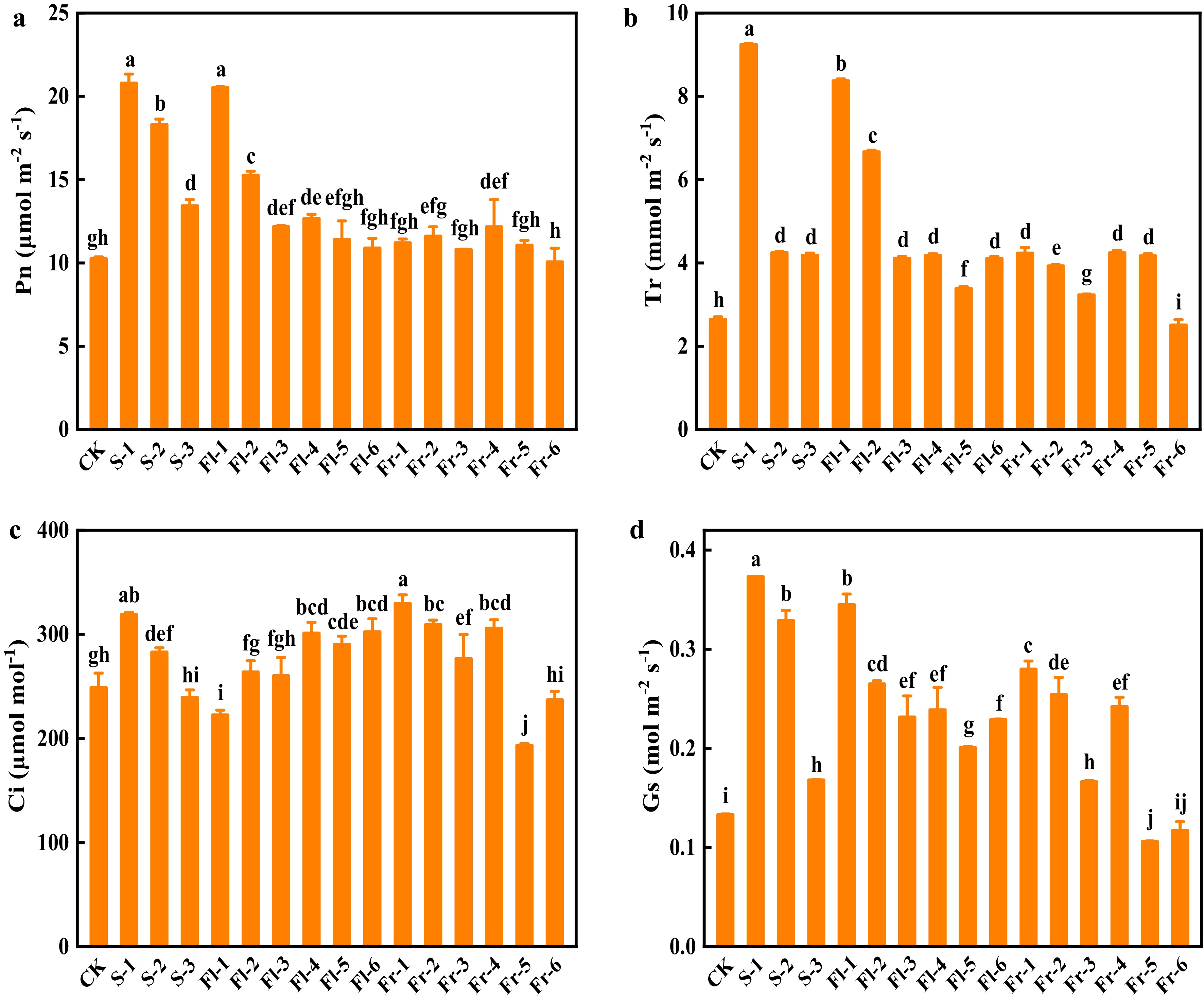

The net photosynthetic rate (Pn) of cucumber plants in the treatments at the seedling stage significantly increased compared with CK, and the effect was positively related to the spraying concentration, among which the plants of S-1 treatment had the highest Pn, and increased by 1.03-fold (Fig. 4a). Similarly, the Pn in the treatments at the flowering stage also decreased with the decrease of spraying concentration, and the effect of spraying mixture every 7 d was better than those in every 14 d at the same concentration (Fig. 4a). Except for Fr-6 treatment, the foliar application of the Put mixture significantly increased the transpiration rate (Tr) (Fig. 4b). The intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci) in the plants of S-1 and Fr-1 treatment increased by 28.6% and 32.6%, respectively, compared with CK (Fig. 4c). Except for Fr-5 and Fr-6 treatment, treatment with Put mixture significantly increased the value of stomatal conductance (Gs) in comparison to CK, especially in S-1 treatment, which was 1.85-fold higher than that in CK (Fig. 4d).

Figure 4.

Effects of the mixture of putrescine (Put), melatonin (MT), proline (Pro), and potassium fulvic acid (MFA) on gas exchange parameters of cucumber under high temperature stress. (a) Net photosynthetic rate (Pn). (b) Transpiration rate (Tr). (c) Intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci). (d) Stomatal conductance (Gs). CK, cucumber plants without treatment with the mixture of 8 mmol L−1 Put, 50 µmol L−1 MT, 1.5 mmol L−1 Pro, and 0.3 g L−1 MFA (Put mixture, original concentration). S, Fl, and Fr indicated cucumber plants-treated with the Put mixture at seedling stage, flowering stage, and fruiting stage, respectively. 1, 2, and 3 indicated cucumber plants-treated with the original, diluted five times, and diluted ten times concentration of the Put mixture every 7 d, 3 times, respectively. 4, 5, and 6 indicated cucumber plants-treated with the original, diluted five times, and diluted ten times concentration of the Put mixture every 14 d, 3 times, respectively. Data represent as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences according to Tukey’s test at P ≤ 0.05.

Effects of Put mixture on fruit yield and quality of cucumber under high temperature stress

-

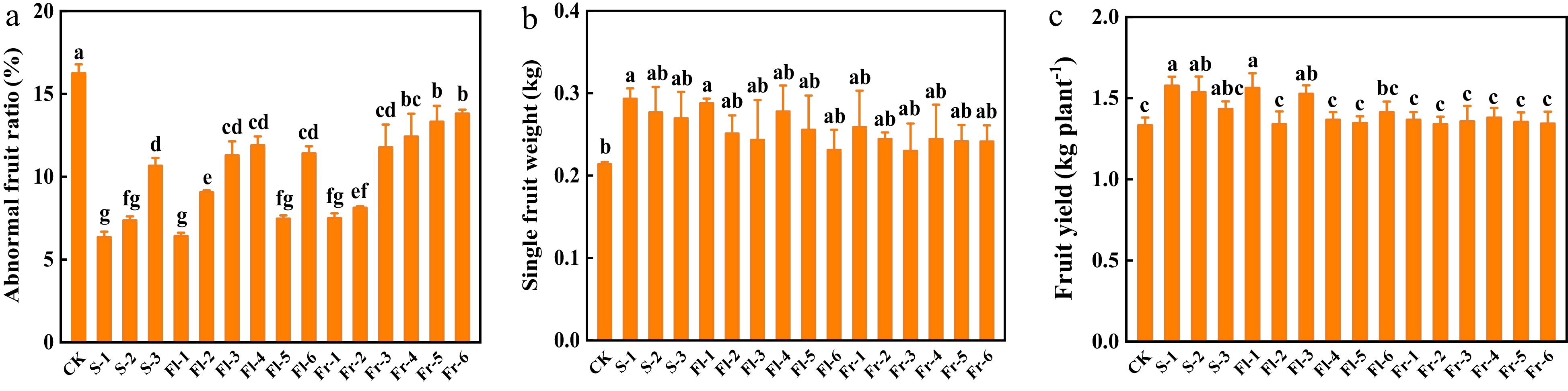

High temperature stress affects cucumber fruit and causes fruit deformity. Spraying Put mixture significantly reduced deformity rate (Fig. 5a). The deformity rate of cucumber fruit in CK was 16.2%, while it was only 6.3% in S-1 treatment, which decreased by 61.1% (Fig. 5a). Furthermore, the foliar application of the Put mixture also increased single fruit weight and fruit yield per plant, and the effect of S-1 treatment was the best, which increased by 38.1% and 18.1%, respectively, in comparison to CK (Fig. 5b & c).

Figure 5.

Effects of the mixture of putrescine (Put), melatonin (MT), proline (Pro), and potassium fulvic acid (MFA) on fruit deformity rate and yield of cucumber. (a) Abnormal fruit ratio. (b) Single fruit weight. (c) Fruit yield per plant. CK, cucumber plants without treatment with the mixture of 8 mmol L−1 Put, 50 µmol L−1 MT, 1.5 mmol L−1 Pro, and 0.3 g L−1 MFA (Put mixture, original concentration). S, Fl, and Fr indicated cucumber plants-treated with the Put mixture at seedling stage, flowering stage, and fruiting stage, respectively. 1, 2, and 3 indicated cucumber plants-treated with the original, diluted five times, and diluted ten times concentration of the Put mixture every 7 d, 3 times, respectively. 4, 5, and 6 indicated cucumber plants-treated with the original, diluted five times, and diluted ten times concentration of the Put mixture every 14 d, 3 times, respectively. Data represent as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences according to Tukey’s test at P ≤ 0.05.

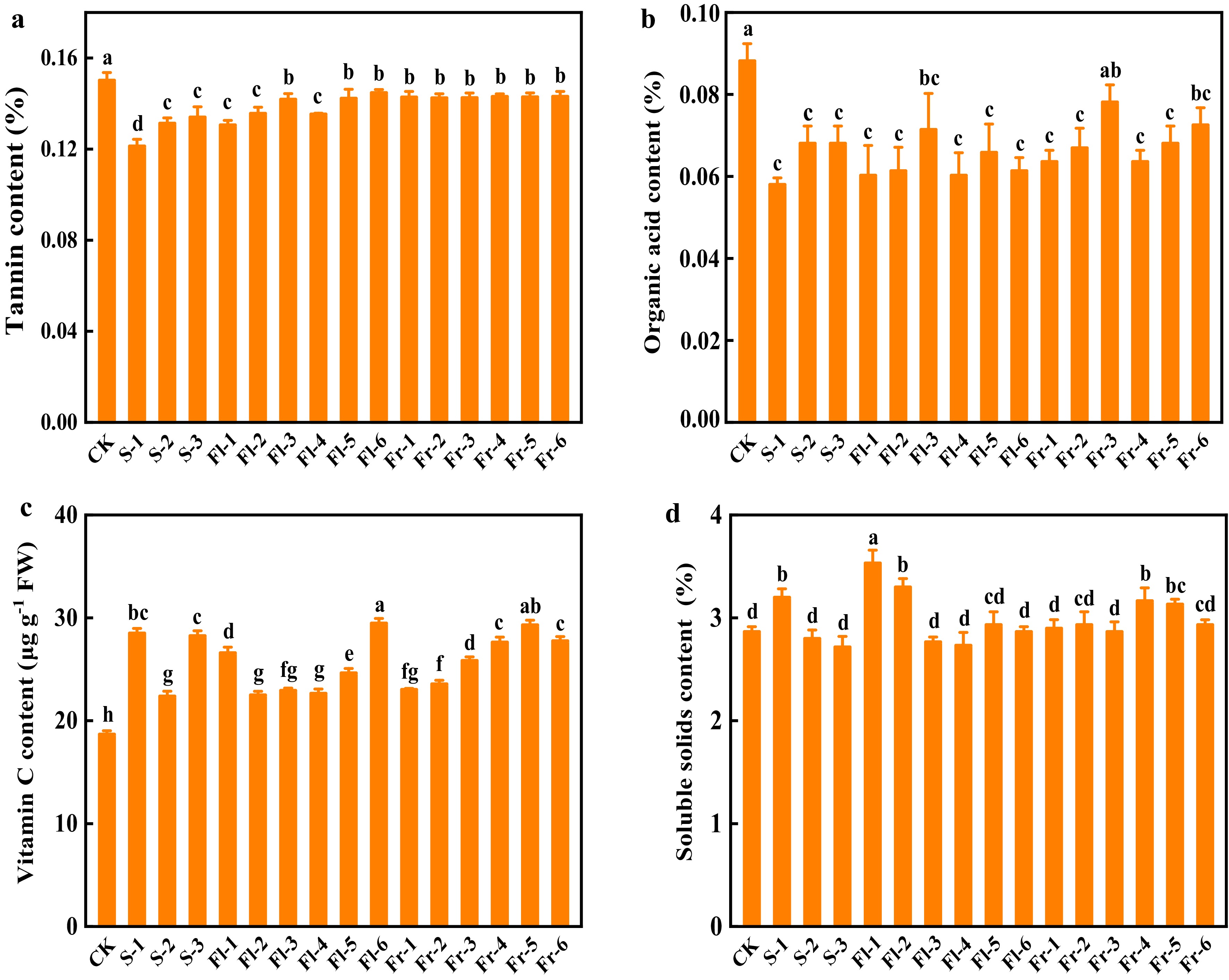

Tannin content of the fruit treated with Put mixture was significantly reduced compared with that in CK (Fig. 6a). At the seedling and flowering stage, tannin content decreased with the increase in spray concentration, and the effect of S-1 treatment was the most profound, which was reduced by 20.0% (Fig. 6a). Except for Fr-3 treatment, the content of organic acid decreased significantly compared to CK (Fig. 6b). The content of organic acid in S-1 treatment was the lowest, which decreased by 34.2% (Fig. 6b). During the fruiting stage, with the increase concentration of spray, the content of organic acid in fruit gradually decreased (Fig. 6b). Compared with CK, all treatments significantly increased the content of vitamin C in cucumber fruit (Fig. 6c). The contents of soluble solids in S-1, Fl-1, Fl-2, Fr-4, and Fr-5 treatments were significantly higher than that in CK (Fig. 6d).

Figure 6.

Effects of the mixture of putrescine (Put), melatonin (MT), proline (Pro), and potassium fulvic acid (MFA) on fruit quality of cucumber. (a) Tannin content. (b) Organic acid content. (c) Vitamin C content. (d) Soluble solids content. CK, cucumber plants without treatment with the mixture of 8 mmol L−1 Put, 50 µmol L−1 MT, 1.5 mmol L−1 Pro, and 0.3 g L−1 MFA (Put mixture, original concentration). S, Fl, and Fr indicated cucumber plants-treated with the Put mixture at seedling stage, flowering stage, and fruiting stage, respectively. 1, 2, and 3 indicated cucumber plants-treated with the original, diluted five times, and diluted ten times concentration of the Put mixture every 7 d, 3 times, respectively. 4, 5, and 6 indicated cucumber plants-treated with the original, diluted five times, and diluted ten times concentration of the Put mixture every 14 d, 3 times, respectively. Data represent as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Different letters indicate significant differences according to Tukey’s test at P ≤ 0.05.

-

High temperature negatively affects plant growth and fruit quality, resulting in leaf wilting, and fruit deformity[38,39]. It has been demonstrated that the foliar application of a moderate concentration of plant growth regulator can ameliorate high temperature stress[2]. In agreement with previous studies, cucumber plants treated with the Put mixture significantly promoted growth under high temperature stress (Fig. 1). Among them, the effect of S-1 treatment was the most obvious on plant height, stem diameter, fresh and dry weight (Fig. 1). In addition, high temperature leads to plant water deficit and oxidative stress, which inhibits plant growth and reduces plant chlorophyll content[40]. The results of this experiment showed that the accumulation of cucumber seedling biomass was inhibited, and the chlorophyll content of CK was lower than that of the Put mixture treatment group under high temperature stress (Figs 1 & 3). Spraying the Put mixture on the leaves alleviated the inhibition of high temperature stress on the growth of cucumber plants.

High temperature often leads to the accumulation of ROS in plants. ROS peroxide with unsaturated fatty acids on the cell membrane and produce a large amount of MDA. MDA further aggravates the oxidation reaction of cell biofilm and causes the destruction of the biofilm structure[41]. Therefore, the content of MDA in plant cells can indirectly represent the degree of oxidative stress. This study showed that treatment with the Put mixture reduced the levels of electrolyte leakage of cucumber leaves, decreased the contents of H2O2 and MDA (Fig. 2), indicating that application of Put mixture alleviated high temperature stress-induced oxidative stress. Similarly, the foliar application of Put removes free radicals and ROS, and reduces the degree of membrane lipid peroxidation under environmental stresses[9, 10]. In addition, Put enhances the scavenging capacity of ROS in chloroplasts by regulating the coordination of antioxidant enzymes and antioxidants in chloroplasts under environmental stress, alleviating the damage of environmental stress to chloroplast structure and function[42−44]. Furthermore, MT is an antioxidant that can scavenge oxygen free radicals and repair its own oxidation products[21,45]. In addition to its direct reaction with ROS, it can enhance the resistance of plants to stress by improving the efficiency of the antioxidant system in plants[21,24,46,47]. Treatment with MFA also improves antioxidant enzyme activity and antioxidant content of plant seedlings under environmental stress to maintain the balance of ROS production and scavenging[48]. Furthermore, Pro maintains the osmotic balance between protoplast and environment through osmotic regulation, reduces water loss, and protects cell membrane structure[49]. This study showed that the foliar application of the Put mixture decreased H2O2 and MDA contents in cucumber leaves (Fig. 2). Therefore, treatment with the Put mixture reduced membrane damage, maintained osmotic balance, reduced oxidative stress, and improved plant high temperature resistance.

Photosynthesis, one of the most important physiological processes in plants, is very sensitive to temperature changes. High temperature stress affects the activity of chlorophyll synthesis enzymes, reduces the content of photosynthetic pigment[50,51], resulting in a reduction of Pn. Studies have shown that single exogenous spraying of Put, MT, Pro, or MFA alleviates the decline of photosynthesis caused by environmental stress through maintaining the structural stability of chloroplasts, scavenging excessive ROS, inhibiting photosynthesis pigment degradation, and increasing the maximum quantum yield of photosystem II[16,27,29,43]. Similarly, this study showed that spraying Put mixture at the seedling stage significantly improved chlorophyll content, Pn, and Tr of plants under high temperature stress, alleviated the reduction of Gs caused by high temperature stress (Figs 3 & 4). The decrease of Pn under high temperature treatment was accompanied by the decrease of Gs and Ci (Fig. 4), indicating that the inhibition of stomatal factors might be the dominant reason for Pn decrease. However, the foliar application of the Put mixture alleviated the decrease of photosynthesis caused by stomatal restriction.

High temperature stress seriously affects cucumber fruit, causing fruit deformity, and reducing fruit yield and quality[38,39]. The foliar application of the Put mixture significantly decreased the rate of deformity, improved fruit yield, the contents of vitamin C and soluble solids in cucumber fruit, and decreased the contents of tannins and organic acids (Figs 5 & 6).

-

The foliar application of the Put mixture promoted plant growth, reduced the level of relative electrolyte leakage and the content of H2O2 and MDA, increased the content of Pro and photosynthesis of cucumber plants. Furthermore, the fruit yield and content of vitamin C and soluble solids increased in Put mixture treated plants, but the content of tannins and organic acids decreased. Therefore, spraying Put mixture on the leaves, especially at the seedling stage with 8 mmol L−1 Put, 50 µmol L−1 MT, 1.5 mmol L−1 Pro, and 0.3 g L−1 MFA every 7 d for three times, alleviated the inhibition of high temperature stress on the growth of cucumber plants, improved cucumber plant adaptability to high temperature stress, and increased the yield and quality.

-

Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L. cv Jinchun No. 4) was used as experimental material. Uniform seeds were sterilized with 10% NaClO for 10 min, followed by washing 5 times with deionized water and soaked in deionized water for 4 h, then the seeds were incubated for germination on moistened filter paper in an incubator (Shanghai Zhicheng Analytical Instrument Manufacturing Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), which was maintained at 28 °C. The germinated seeds were sown in 32-well plastic trays filled with seedling substrates (Jiangsu Xingnong Substrate Technology Co., Ltd., China) and grown in the greenhouse of Baima Teaching and Research Base of Nanjing Agricultural University. The temperature in the greenhouse during the day was controlled at 25−28 °C, the temperature at night was 18−20°C, and the relative humidity was maintained at 75%−80%. When the fourth leaves were fully expanded, the seedlings were selected and planted in coconut coir substrates (Van der Knaap Group of Companies, Wateringen, Netherlands) on Apr. 17, 2021 in the same greenhouse. As shown in Supplemental Fig. S1, the maximum temperature was over 30 °C in the most of the cultivation period, indicating that cucumber plants suffered from high temperature stress.

Experimental design

-

Cucumber seedlings were randomly divided into 16 groups to treat with or without Put mixture, and each group contained 15 plants as one treatment. As shown in Table 1, cucumber plants without treatment with the mixture of 8 mmol L−1 Put, 50 µmol L−1 MT, 1.5 mmol L−1 Pro, and 0.3 g L−1 MFA (Put mixture, original concentration) were used as CK. S-1, S-2, and S-3 indicated cucumber plants treated with the original, diluted five times, and diluted ten times concentration of Put mixture at seedling stage every 7 d, 3 times, respectively. Fl-1, Fl-2, and Fl-3 indicated cucumber plants treated with the original, diluted five times, and diluted ten times concentration of Put mixture at flowering stage every 7 d, 3 times, respectively. Fl-4, Fl-5, and Fl-6 indicated cucumber plants treated with the original, diluted five times, and diluted ten times concentration of Put mixture at flowering stage every 14 d, 3 times, respectively. Fr-1, Fr-2, and Fr-3 indicated cucumber plants treated with the original, diluted five times, and diluted ten times concentration of Put mixture at fruiting stage every 7 d, 3 times, respectively. Fr-4, Fr-5, and Fr-6 indicated cucumber plants treated with the original, diluted five times, and diluted ten times concentration of Put mixture at fruiting stage every 14 d, 3 times, respectively.

Table 1. Spraying concentration and stage of cucumber with putrescine mixture.

Treatment Putrescine

concentration

(mmol L−1)Potassium fulvic acid concentration

(g L−1)Proline

concentration

(mmol L−1)Melatonin

concentration

(µmol L−1)Spraying interval (d) Spraying stage CK − − − − − S-1 8 0.3 1.5 50 7 Seedling stage S-2 1.6 0.06 0.3 10 7 Seedling stage S-3 0.8 0.03 0.15 5 7 Seedling stage Fl-1 8 0.3 1.5 50 7 Flowering stage Fl-2 1.6 0.06 0.3 10 7 Flowering stage Fl-3 0.8 0.03 0.15 5 7 Flowering stage Fl-4 8 0.3 1.5 50 14 Flowering stage Fl-5 1.6 0.06 0.3 10 14 Flowering stage Fl-6 0.8 0.03 0.15 5 14 Flowering stage Fr-1 8 0.3 1.5 50 7 Fruiting stage Fr-2 1.6 0.06 0.3 10 7 Fruiting stage Fr-3 0.8 0.03 0.15 5 7 Fruiting stage Fr-4 8 0.3 1.5 50 14 Fruiting stage Fr-5 1.6 0.06 0.3 10 14 Fruiting stage Fr-6 0.8 0.03 0.15 5 14 Fruiting stage Measurement of plant growth parameters

-

The plant growth parameters were measured after planting for 40 d. Plant height was measured from the stem base to the growth point with a ruler, and stem diameter was measured with a vernier caliper, 1 cm below the cotyledons. Fresh samples were washed with distilled water and dried with paper, and then fresh weight was weighed with an electronic scale. The samples were dried for 15 min at 105 °C in an oven (Shanghai Yiheng Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), and the temperature was reduced to 75 °C until constant weight was obtained.

Determination of photosynthesis

-

The Pn, Gs, Ci, and Tr of the fifth fully expanded leaf below the growth point were measured with a portable photosynthesis system (LI-6400; Li-COR, Lincoln, NE, USA) from 9:00 to 11:00 am after planting for 40 d. The measurement parameters were as follows: ambient CO2 concentration was 380 µmol mol−1, the leaf chamber temperature was maintained at 25 °C, and the photosynthetic photo flux density was 800 µmol m−2 s−1.

Determination of relative electrolyte leakage and MDA content

-

Relative electrolyte leakage was detected according to the method described previously[52]. The content of MDA was determined using the thiobarbituric acid method[53].

Determination of Pro content

-

Fresh leaves were washed, cut into pieces and 0.2 g samples were placed in a 15-ml centrifuge tube. Five millilitres of 3% sulfosalicylic acid solution was added into the tubes, and extracted in a boiling water bath for 10 min (shaken every 5 min). After cooling, the tubes were centrifuged at 3000 r for 10 min and 1 ml of the supernatant was placed in a new tube, adding 1 ml of distilled water, 1 ml of glacial acetic acid, and 2 ml of acidic ninhydrin solution. Subsequently, the tubes were heated in a boiling water bath for 60 min. Four millilitres of toluene was added to the tube after cooling, and vortexed for 30 s. The upper layer of toluene Pro red solution was used to measure Pro concentration at 520 nm using a UV-1800 spectrophotometer (Shanghai Unico Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) as previously described[54].

Measurement of H2O2 and chlorophyll content

-

Cucumber leaves (0.2 g) were ground to homogenate in 1.6 ml of 0.1% TCA on ice and centrifuged at 12000 r for 20 min. The supernatant (0.2 ml) was added to 1 ml of 1 mol L−1 KI and 0.25 ml of 0.1 mol L−1 potassium phosphate buffer (pH = 7.8) for reaction for 1 h in the dark. The concentration of H2O2 was measured at 390 nm using a spectrophotometer and calculated as previously described[55].

For the measurement of chlorophyll content, 20 ml of 95% ethanol was added to 0.2 g of fresh leaves and sealed. The tubes were placed in the dark for 24−36 h until the leaves turn white. The chlorophyll content was measured according to the method of Arnon[56].

Fruit yield and quality measurements

-

Ten plants were labeled in each treatment for yield measurement. Fruit weight was measured each time after picking, and the yield per plant was calculated after harvest. Six fresh ripe cucumbers were collected from each treatment during the fruit stage, and the fruit soluble solids, tannins, organic acid, and vitamin C content were determined to evaluate the fruit quality.

The content of soluble solids was detected as previously described[57]. Briefly, the content of soluble solids was determined using an Abbe refractometer (WZ-108, Beijing Wancheng Beizeng Precision Instrument Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Before determination, the refractometer was calibrated with a standard sample and then the content of soluble solids was analyzed and determined.

For measuring tannin content, cucumber fruit (5 g) was ground and transferred to a 150-ml conical flask, shaken and extracted for 15 min. Five millilitres of 1 mol L−1 zinc acetate standard solution and 3.5 ml of concentrated ammonia were added into a 100-ml volumetric flask, shaken, and the tannin extraction was slowly transferred into the volumetric flask, keeping it warm in a 35 °C water bath for 30 min with shaking. After cooling, the volume was adjusted to 100 ml with distilled water, fully mixed and filtered. Ten millilitres of filtrate was placed in a 150-ml conical flask, and 40 ml of distilled water, 12.5 ml of NH3-NH4Cl, and 10 drops of chrome black T indicator were added and mixed well. The mixture was titrated with 0.05 mol L−1 EDTA solution until the wine red changed to pure blue. The content of tannin was calculated as previously described[58].

To measure the content of organic acid, cucumber fruits (5 g) were ground and washed into a 250-ml conical flask with distilled water to make the volume to 100 ml. Organic acids were extracted in a constant temperature water bath at 80 °C for 30 min and shaken continuously. After cooling, the extractions were filtered and the residues were washed with distilled water 3 times; the filtrate was mixed and fixed to 100 ml with distilled water. The organic acid content was titrated with 0.1 mol L−1 sodium hydroxide standard solution as previously described[59].

The content of vitamin C was determined according to the method previously described[60].

Statistical analysis

-

All data were statistically analyzed using the SPSS 18.0 version (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and the results are presented as means ± SDs (n = 3). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test for significance, and the significance between treatments were analyzed with Tukey’s honestly significant difference test (HSD) at P < 0.05.

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2019YFD1001902).

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplemental Fig. S1 Temperature records registered in the greenhouse where the experiment was performed.

- Copyright: © 2022 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wang Y, Liu H, Lin W, Jahan MS, Wang J, et al. 2022. Foliar application of a mixture of putrescine, melatonin, proline, and potassium fulvic acid alleviates high temperature stress of cucumber plants grown in the greenhouse. Technology in Horticulture 2:6 doi: 10.48130/TIH-2022-0006

Foliar application of a mixture of putrescine, melatonin, proline, and potassium fulvic acid alleviates high temperature stress of cucumber plants grown in the greenhouse

- Received: 24 January 2022

- Accepted: 18 July 2022

- Published online: 29 September 2022

Abstract: Putrescine (Put), melatonin (MT), proline (Pro), and potassium fulvic acid (MFA) are widely used as plant growth regulators to enhance stress tolerance. However, the roles of their mixtures in response to stress are largely unknown. Here, we mixed Put with MT, Pro, and MFA (hereafter referred to as Put mixture) with different concentrations and foliar sprayed at different growth stages (seedling, flowering, and fruiting stage) of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) to investigate their roles on plant growth, fruit yield, and quality under high temperature stress. The foliar application of the Put mixture promoted cucumber growth, increased chlorophyll and Pro contents and net photosynthesis rate, and reduced the values of relative electrolyte leakage, H2O2 and malondialdehyde contents of cucumber leaves, indicating that treatment with Put mixture reduced the oxidative stress caused by high temperature. Furthermore, Put mixture-treated cucumber plants had lower fruit deformity rate and higher fruit yield compared with control. The contents of vitamin C and soluble solids of cucumber fruit significantly increased and the contents of tannin and organic acid decreased. The most profound effects were found in the plants treated with 8 mmol L−1 Put, 50 µmol L−1 MT, 1.5 mmol L−1 Pro and 0.3 g L−1 MFA every 7 d, three times at the seedling stage, indicating that cucumber seedlings treated with the mixture of Put, MT, Pro, and MFA significantly alleviated the negative effects of high temperature stress.

-

Key words:

- putrescine /

- melatonin /

- proline /

- potassium fulvic acid /

- cucumber /

- high temperature