-

Cancer is a cluster of diseases and STAT3 protein has significant roles in all types of cancer. Signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), belong to the family of cytoplasmic transcription factors, activate and transduce extracellular growth factor, and also affect cytokine signals and affect gene transcriptional events. STAT3 mutant intrinsically alone is enough to instigate oncogenic transformation, and tumorigenesis[1−3]. A survey of the current literature reveals that STATs have transactivated domains and play a significant role in cancer migration and invasion. Hampering of c-Src kinase activity or downregulation of STAT3 signaling stimulates apoptosis[4]. The study of chemical interactions between STAT3 receptor and phytochemicals assist in drug designing and hence in cancer therapy[5]. There are a variety of phytochemicals that have a high propensity to modulate directly or indirectly the STAT3 signaling pathway. Triterpenoids like betulinic acid, polyphenols curcuminoids, plumbagin a naphthoquinone, diosgenin a steroid, hydroxycinnamic acid, and thymoquinone are the phytochemicals that suppress STAT3 expression[6]. Many plant-derived phytochemicals manifest high anticancer activity and lead researchers to adopt integrated multifaceted research techniques[7−11]. Though, Elaeocarpus ganitrus Roxb. (also known as Rudraksha) constitutively placed in Ayurvedic system, also has anticancer potential[12]. Recently its silver nanoparticle has been assessed for anticancer and antiproliferative activities[13]. Its impact on STAT is yet to be explored. In the last few decades, phytochemical composition of Elaeocarpus genus has been extensively investigated. Phytochemicals of various extracts of different parts of the plant showed the presence of alkaloids, flavonoids, carbohydrates, glycosides, proteins, quinine, coumarins, tannins, minerals, vitamins, saponins, phenolic compounds, and fixed oils in a high concentration, thus adding to its medicinal value[14]. The pharmacological screening of metabolites like polyphenols, alkaloids, terpenoids and flavonoids have been explored to demonstrate cancer pathways to ascertain possible mechanism[15−18]. As stated in the literature, the beads and the bark of the plants have been extensively studied while the leaves of the E. ganitrus have not been studied for their anticancer efficiency. Besides, leaves of the plants were shown to have good antioxidant potential[19,20]. The emphasis of the study is to identify phytochemicals retrieved from Elaeocarpus ganitrus leaf research data and GC-MS profiling. To accentuate, the binding role of Elaeocarpus ganitrus phytochemicals with STAT3 receptor, their ADME properties and pharmacokinetic studies were investigated.

-

The chemicals and solvents used in the extraction and phytochemical analysis were of analytical grade, sourced from Sigma-Aldrich. MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-1yl]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) was also procured from Sigma-Aldrich. HeLa cells were obtained from the National Centre for Cell Sciences (NCCS), Pune, India. Fetal bovine serum and Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Media were acquired from Gibco-life technologies.

Procurement of plant material

-

Fresh leaves of E. ganitrus were purchased from Patanjali Herbal Garden Nursery in Panchayanpur, Uttarakhand, India. Authentication of the Elaeocarpus ganitrus was conducted by the Department of Botany, Jamia Hamdard, New Delhi, India, and the voucher specimen was deposited at the University.

Method to prepare extracts

-

Leaves of E. ganitrus were carefully washed, air-dried for ten days, and ground to a fine powder. A sample of 1,000 grams of powder was exhaustively extracted three times with 100% methanol (10 times weight/volume) at room temperature for 72 h using a soxhlet apparatus. The resulting crude methanol extract was fractionated successively with solvents in increasing polarity order: heptane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, methanol, and water. The residue was air-dried and utilized for the subsequent solvents. The fractions obtained from each solvent were filtered, dried under vacuum using a rotary evaporator, and stored at 40 °C until use[21].

Qualitative phytochemical analysis

-

The presence or absence of phytochemicals such as terpenoids, steroids, saponins, flavonoids, glycosides, tannins, and phenols in the chloroform and methanol extracts of E. ganitrus leaves was determined following the standard methodology[22].

Cellular studies on HeLa cancer cell line

-

The HeLa cell line was stored in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium which is rich in 10% Fetal Bovine Serum, 1% antibiotic solution, 25 mM sodium bicarbonate, and 10 mM HEPES in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere at 37 °C in an air jacketed incubator. The stock culture was perpetuated in the exponentially growing phase by passaging as, monolayer culture with 0.02% EDTA. Dislodged cells suspended in complete medium were routinely reseeded.

Cytotoxicity assay/MTT assay

-

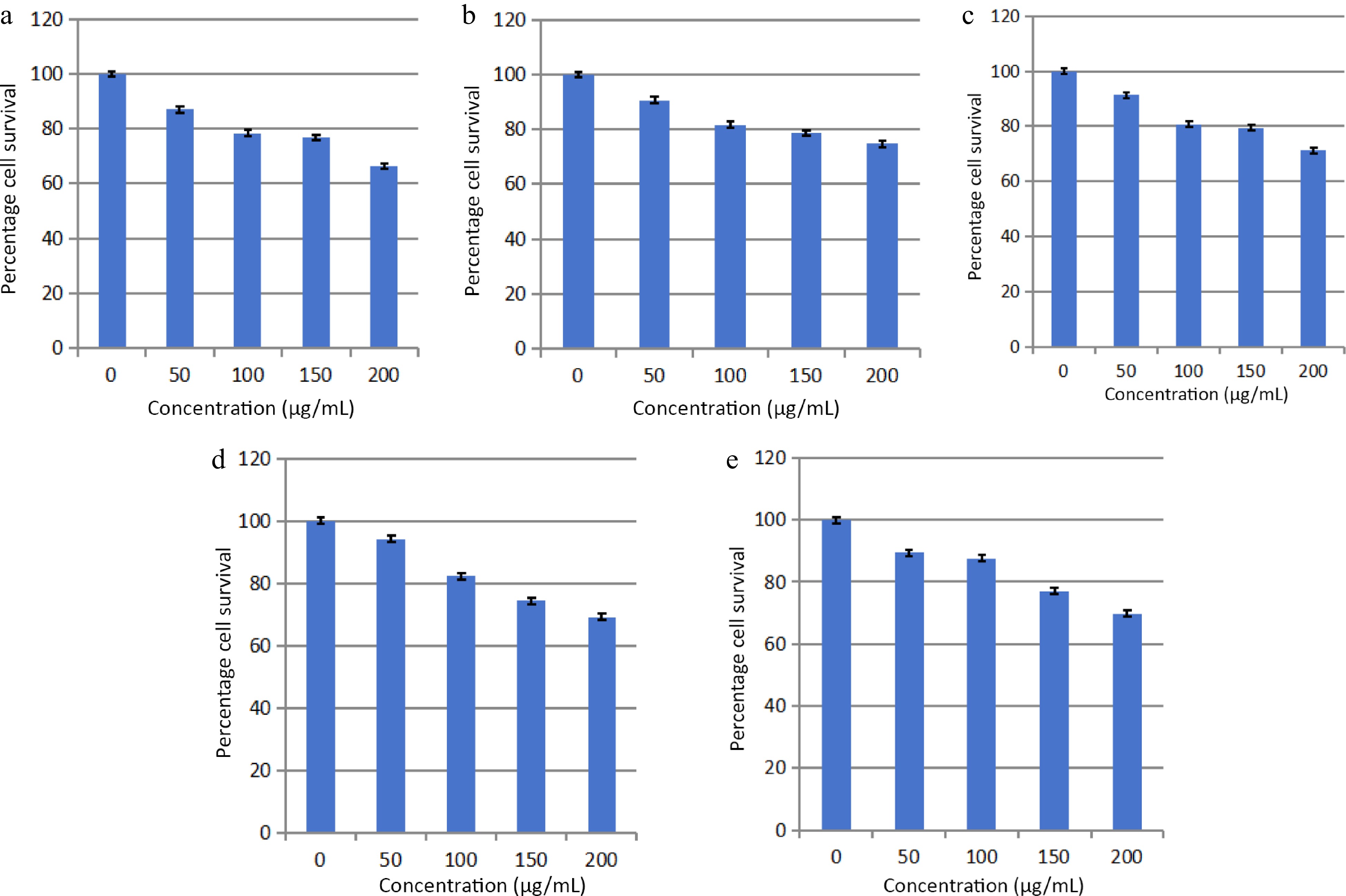

The cytotoxic effects of the various fractions of E. ganitrus leaf on the HeLa cancer cell line were evaluated using the MTT assay. Cells were seeded overnight, and exposed to different concentrations of the prepared fractions (ranging from 50 to 200 μg/ml), and incubated for 48 h. After treatment, cells were incubated with MTT solution and the formazan crystals were solubilized and the absorbance was read at 570 nm[23].

In silico investigation of phytochemicals obtained from leaf extracts

-

Binding energies of phytochemicals retrieved from plant leave extract with STAT3 were calculated by using software InstaDock for molecular docking. Discovery Studio Visualizer, and PyMOL, were used to visualize the chemical interactions of ligands and proteins. SWISS-ADME tool and ProTox-II were used for pharmacokinetic profiling studies. The X-ray crystal structure of STAT3 (PDB ID: 6NJS) was downloaded from Protein Data Bank (PDB). All co-crystallized hetero atoms and attached water molecules and co-crystallized ligands, were eliminated from the original coordinates. The Polar hydrogen atoms were inculcated, the residue structures having lower occupancy were removed, and the incomplete side chains were then substituted by using ADT. Three-dimensional structures of phytocompounds were sketched using Chem3D.

Drug-likeness properties prognosis

-

Determination of the analogous behavior to the drug of phytoligands with the help of cheminformatics was done using online tool SwissADME developed by the Molecular Modelling Group, Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics[24]. The computation of pharmacokinetics and physicochemical molecular properties help medicinal chemists in their routine drug discovery processes. Significant basic molecular information can be excavated from the chemical structure. The methods were preferred over other methods because of the speed, but also for the ease of interpretating results by fingerprinting method to enable researchers move through translation to medicinal chemistry and in molecular designing[25].

Molecular docking-based virtual screening

-

The rationale behind molecular docking is to steer medicinal chemists for translational research. The affinity of a molecule to the receptor changes with small structural changes in the molecule[26]. For molecular docking, STAT3 core complex PDB id (PMID: 31715132) was remodeled to ascertain binding energies with the best conformational poses of Elaeocarpus ganitrus leaves phytoligands. The InstaDock software is used to dock phytoligands with blind search space having a grid size of 110, 70, and 108 Å for X, Y, Z coordinates, correspondingly. The center of the grid was confined to X: 63.09, Y: 14.98, and Z: −76.91 axis, which covers all the heavy atoms embedded in the protein. The conformational site selected was so that the movement of the ligands was free to probe their best binding coordinates. Default docking specifications were employed to calculate various parameters. All the docking conformational poses were generated using PyMOL, a molecular visualization system and Discovery Studio Predictor.

Pharmacokinetic and toxicity prediction

-

Physicochemical parameters, water solubility, lipophilicity, pharmacokinetics, and drug-likeness were elicited from SwissADME. To retrieve the toxicological profile of the phytoligands ProTox-II servers were employed[27]. Early estimation of the Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion and Toxicity abbreviated as ADMET imperative to ascribe the pharmacodynamics success of the lead phytoligands. (SMILES) strings to encode chemical structures were imported from PubChem, open chemistry database and implemented in SWISS-ADME tool[24] to auspicate lipophilicity to show hydrophobic and hydrophilic nature, water solubility, necessary for absorption across membranes, and drug-likeness rules to assess metabolic profiles. Toxicology prediction of phytoligands is a crucial and fundamental aspect in the drug discovery process. ProTox-II is used to estimate computational toxicity, to accelerate the course to drug discovery, compute animal toxicity, and also help to attenuate animal experiments. In the PROTOX-II web server, toxicity classes are designated into four segments. Category I comprised of chemical entities with LD50 (LD = lethal Dose) values (LD50 ≤ 5) mg/kg, Category II comprised of compounds with LD50 values (5 < LD50 ≤ 50) mg/kg, Category III comprised of chemical entities having LD50 values (50 < LD50 ≤ 300) mg/kg, Category IV comprised of compounds which have LD50 values (300 < LD50 ≤ 2,000) mg/kg, Category V comprised of compounds with LD50 values (2,000 < LD50 ≤ 5,000) mg/kg and Category VI comprised of compounds showing LD50 values (LD50 > 5,000) mg/kg[28]. Category I and II manifested high toxicity, Category III and IV are comparatively less toxic and Category V and VI are considered to be non-toxic.

-

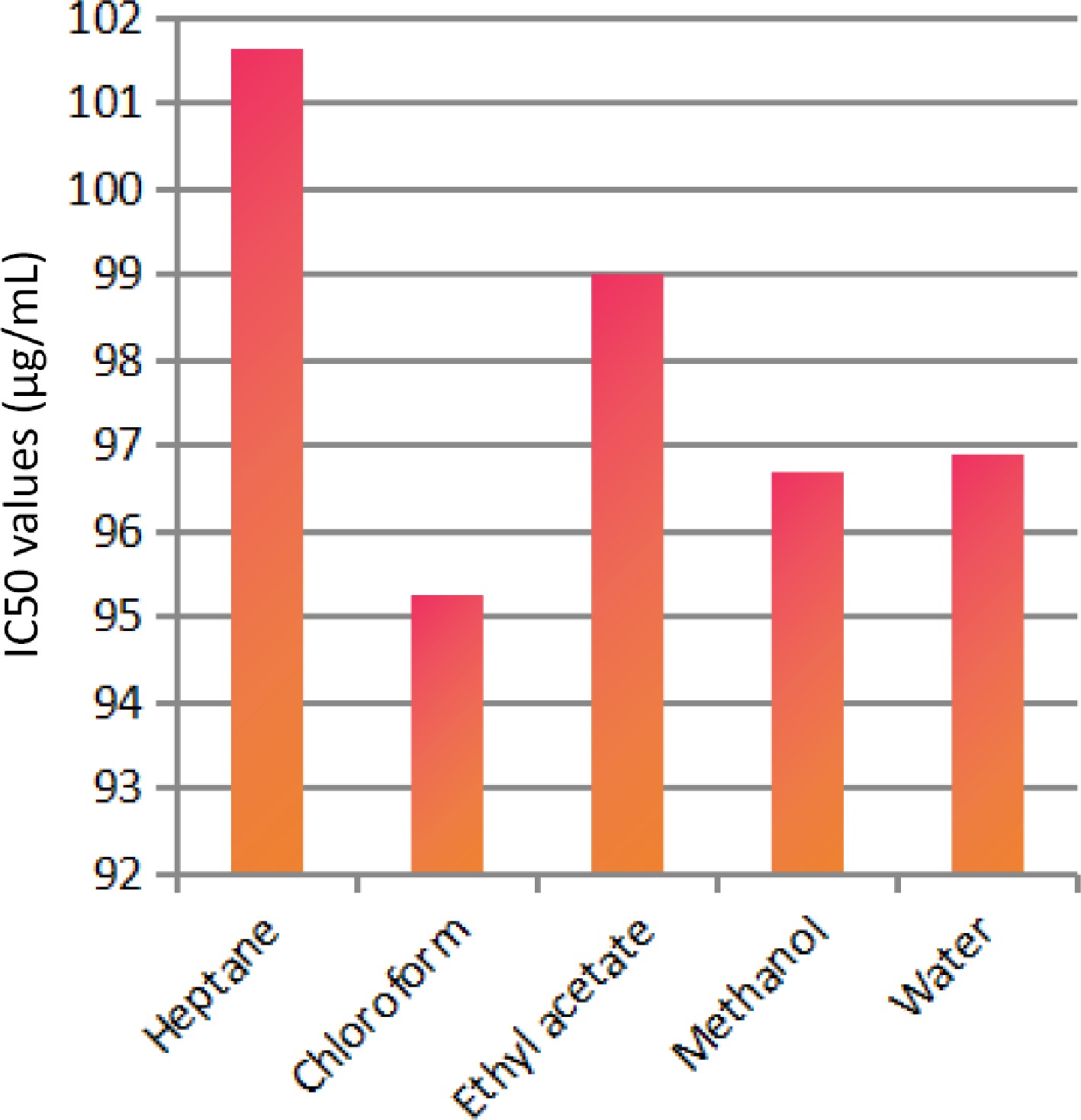

The solvent extraction technique is usually employed to prepare extracts from plant materials attributable to its convenience to operate. The importance lies in that a large amount of plant material can be extracted with minimal solvent[26]. Fresh leaves of Elaeocarpus ganitrus were purchased from Patanjali Herbal Garden Site Nursery located in Panchayanpur, Uttarakhand 249405, India. The confirmation of the authenticity of the Elaeocarpus ganitrus was done by the Department of Botany, Jamia Hamdard, New Delhi, India, and the leaf specimens deposited in the University. The crude methanol extract was unintermittedly fractionated in the solvents heptane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, methanol, and water according to their increasing polarity[16]. The anticancer activity of extracts was analyzed on the basis of their IC50 values. Cancerous HeLa cell line when treated with E. ganitrus leaf extracts exhibited a substantial inhibition of cells. The half maximal inhibitory concentration of chloroform and methanol extracts of E. ganitrus was (IC50 = 304.39 μg/ml) and (IC50 = 308.59 μg/ml) respectively followed by water (IC50 = 340.14 μg/ml), ethyl acetate (IC50 = 350.72 μg/ml) and heptane (IC50 = 381.76 μg/ml) extracts (Fig. 1a−e & Fig. 2). The qualitative investigation using standard methodology[22] of chloroform and methanol fractions of E. ganitrus leaves disinterred the presence of major phytochemicals namely steroids, saponins, terpenoids, tannins, phenols, glycosides and flavonoids Table 1. GC-MS analysis of the chloroform and methanolic fractions was done based on their lowest half maximal inhibitory concentration to get a complete profiling of the plant compounds. The peaks in the total ion current (TIC) chromatogram of GC-MS profile of the phytoligands commensurate with the spectrum of known chemical databases stockpiled in the GC-MS library. The gas chromatogram depicts the relative concentrations of different phytoligands getting eluted according to the retention time. The heights of the peak represent the comparative concentrations of the compounds present in the plant appear as peaks at different m/z ratios. The components present with their retention time, molecular formula, molecular weight and concentration (peak area %) are provided in Tables 2 & 3 showing the presence of 56 and 50 bioactive phytochemicals in the chloroform and methanol extracts respectively. Of 106 phytoligands obtained from chloroform and methanol extracts of E. ganitrus leaves, 81 phytoligands were identified has having the best drug-like properties following Lipinski's rule of five. Lipinski's rule states that molecular properties, physical or chemical of a compound are significant for a drug's pharmacokinetics behavior inside a biological system. The drug molecules that go along with the RO5 have fewer attrition rates when undergoing clinical trials. The cheminformatics study to identify potential chemical entities having propensity for predefined biological targets is called virtual screening[28]. To endeavor in vitro experiments time diminution, molecular docking-based virtual screening of 81 selected compounds with two reference inhibitors having substantial binding energies with 6NJS were preferred for further analysis. The STAT3 has dual nature as an oncogene or as a tumor suppressor during cancer progression. It has a SH2 domain, linker domain, DNA binding domain, and all-alpha domain. The total energy of binding, Vander Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, electrostatic attraction, desolvation, and also a number of rotatable bonds present in the phytoligand, contribute to observe the free energy of binding of phytoligands with the receptor. Twenty-six (EG-1 to EG-26) compounds were selected as having appreciable binding affinities towards the 6NJS receptor (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Effects of (a) heptane, (b) chloroform, (c) methanol, (d) ethyl acetate and (e) water fractions of E. ganitrus leaves on the human cancer cell lines HeLa using MTT assay.

Figure 2.

IC50 values of different extracts of E. ganitrus leaves against human cancer cell lines HeLa.

Table 1. Qualitative analysis of phytochemicals in E. ganitrus leaf extracts.

Tested compounds Chloroform extract Methanol extract Steroids + + Terpenoids + + Saponins + + Glycosides + + Tannins + + Flavonoids + + Phenols + + + → Present; − → Absent. Table 2. GC–MS analysis of chloroform fraction of E. ganitrus leaves.

Peak no. R. Time Area Area % Name 1 7.328 3392451 3.60 Phenol, 2-methoxy-4-(2-propenyl)- 2 7.494 432542 0.46 Cyclododecane 3 7.925 5018874 5.32 Bicyclo[7.2.0]undec-4-ene,4,11,11-trimethyl-8-methylene- 4 8.392 264573 0.28 1,4,8-Cycloundecatriene, 2,6,6,9-tetramethyl-,(e,e,e)- 5 9.137 1568546 1.66 Phenol, 3,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- 6 10.016 2727130 2.89 1-Heptadecene 7 12.221 2959933 3.14 1-Octadecene 8 12.670 178963 0.19 Neophytadiene 9 12.782 147893 0.16 2-Pentadecanone, 6,10,14-trimethyl- 10 13.496 127511 0.14 7,9-Di-tert-butyl-1-oxaspiro(4,5)deca-6,9-diene-2,8-dione 11 13.594 2105374 2.23 Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester 12 13.801 186096 0.20 Isophytol 13 14.003 2582987 2.74 Dibutyl phthalate 14 14.233 126402 0.14 1-Nonadecene 15 15.143 262912 0.28 1-Octadecanol 16 15.196 409325 0.43 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (z,z)-, methyl ester 17 15.256 1418833 1.50 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid, methyl ester, (z,z,z)- 18 15.396 8267193 8.76 P-menth-1-ene-3,3-d2 19 15.776 4268486 4.53 Cholest-24-ene, (5.alpha.,20.xi.)- 20 16.081 1835125 1.95 Behenic alcohol 21 17.015 574682 0.61 Glycidyl palmitate 22 17.502 356762 0.38 4,8,12,16-Tetramethylheptadecan-4-olide 23 17.792 1548266 1.64 N-tetracosanol-1 24 18.507 892966 0.95 Glycidyl oleate 25 18.633 387075 0.41 Pentacosane 26 18.885 1160812 1.23 Hexadecanoic acid, 2-hydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethyl ester 27 18.949 2520126 2.67 1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid 28 19.383 1722880 1.83 Hexacosyl pentafluoropropionate 29 19.997 295789 0.31 Carbonic acid, propyl 3,5-difluophenyl ester 30 20.152 1655981 1.76 Tetracontane 31 20.287 718350 0.76 9-Otadecenoic acid (z)-, 2,3-dihydroxypropyl ester 32 20.437 1633424 1.73 Octadecanoic acid, 2,3-dihydroxypropyl ester 33 20.875 8530902 9.04 Carbonic acid, eicosyl prop-1-en-2-yl ester 34 21.225 1169791 1.24 .alpha.-tocospiro b 35 21.371 1475710 1.56 .alpha.-tocospiro b 36 21.566 2790793 2.96 Tetracosane 37 21.619 566554 0.60 1-Heptacosanol 38 21.978 208285 0.22 Tetracontane 39 22.244 3146831 3.34 Tetracontane 40 22.339 198857 0.21 Triacontyl acetate 41 22.758 602558 0.64 .gamma.-tocopherol 42 22.987 3769661 4.00 Tetracontane 43 23.083 307563 0.33 Octacosanol 44 23.368 804368 0.85 2,5,7,8-Tetramethyl-2-(4,8,12-trimethyltridecyl)-3,4-dihydro-2h-chromen-6-yl hexofuranoside 45 23.832 2825781 3.00 Hexatriacontane 46 24.442 224749 0.24 Ergost-5-en-3-ol 47 24.697 146326 0.16 2,6,10,15,19,23-Hexamethyl-tetracosa-2,10,14,18,22-pentaene-6,7-diol 48 24.816 2579206 2.73 Tetracontane 49 25.344 4403683 4.67 .gamma.-sitosterol 50 25.897 247451 0.26 Phenol, 2,4-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-, phosphite (3:1) 51 25.971 1050990 1.11 Tetracontane 52 27.369 1062263 1.13 Tetracontane 53 29.049 4468338 4.74 Benzenepropanoic acid, 3,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-hydroxy-,octadecyl ester 54 31.061 859726 0.91 Tetrapentacontane 55 33.505 689017 0.73 Tetrapentacontane 56 36.515 570264 0.60 Tetrapentacontane Table 3. GC–MS analysis of methanol fraction of E. ganitrus leaves.

Peak no. R. time Area Area % Name 1 4.562 1716062 2.75 4h-pyran-4-one, 2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl- 2 5.545 132891 0.21 1,5-Dimethyl-1-vinyl-4-hexenyl 2-aminobenzoate 3 6.130 66420 0.11 E-6-octadecen-1-ol acetate 4 6.658 9826941 15.75 4-Hydroxy-3-methylacetophenone 5 7.421 59260 0.09 1-Undecanol 6 7.746 290020 0.46 Methyl2,3,6,7-tetra-o-acetyl-4-o-methyl-.beta.-glycero-d-glucoheptopyranoside 7 8.935 1932769 3.10 Guanosine 8 9.178 535822 0.86 1,3:2,5-Dimethylene-l-rhamnitol 9 9.949 463870 0.74 Octadecanoic acid 10 10.144 279041 0.45 1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid, diethyl este 11 10.370 1683966 2.70 .alpha.-methyl-l-sorboside 12 10.606 1300727 2.08 .alpha.-d-galactopyranoside, methyl 13 10.920 280573 0.45 Butanoic acid, 3-methyl-, hexahydro-4- methylspiro[cyclopenta[c]pyran-7(1h),2'-oxirane]-1,6-diyl ester 14 11.090 80380 0.13 Tricyclo[7.2.0.0(2,6)]undecan-5-ol, 2,6,10,10-tetramethyl- (isomer 3) 15 11.224 161606 0.26 .alpha.-d-galactopyranoside, methyl 16 11.492 189485 0.30 Octadecanoic acid, methyl ester 17 12.437 260634 0.42 2(4h)-benzofuranone, 5,6,7,7a-tetrahydro-6- hydroxy-4,4,7a-trimethyl-, (6s-cis)- 18 12.643 123768 0.20 Neophytadiene 19 13.565 2866045 4.59 Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester 20 13.780 34044 0.05 1-hexadecen-3-ol, 3,5,11,15-tetramethyl- 21 13.910 47535 0.08 Silane, ethenylethyldimethyl- 22 14.555 73535 0.12 Pentadecanoic acid, methyl ester 23 15.188 1768899 2.83 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (z,z)-, methyl ester 24 15.249 5971407 9.57 (9e,12e)-9,12-octadecadienoyl chloride # 25 15.385 7933212 12.71 1,1'-Bicyclohexyl, 2-methyl-, cis- 26 15.481 910073 1.46 Methyl stearate 27 15.758 8239629 13.21 Cholest-24-ene, (5.alpha.,20.xi.)- 28 16.075 396431 0.64 Methyl octadeca-9,12-dienoate 29 16.444 77246 0.12 Methyl 4-(dimethylamino)bicyclo[2.2.2]oct- 5-ene-2-carboxylate 30 16.612 54809 0.09 Hexadecanoic acid, 2-hydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethyl ester 31 16.999 215619 0.35 17-octadecynoic acid 32 17.249 219061 0.35 Eicosanoic acid, methyl ester 33 18.127 232480 0.37 Oleoyl chloride 34 18.509 301125 0.48 Undec-10-ynoic acid, undec-2-en-1-yl ester 35 18.705 135332 0.22 Hexadecanoic acid, 1-(hydroxymethyl)-1,2-ethanediyl ester 36 18.899 4607864 7.38 Hexadecanoic acid, 2-hydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethyl ester 37 19.655 106312 0.17 Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester 38 20.300 580671 0.93 Oleoyl chloride 39 20.462 994304 1.59 Octadecanoic acid, 2,3-dihydroxypropyl ester 40 20.912 3584027 5.74 9-octadecenamide 41 21.225 221450 0.35 .alpha.-tocospiro b 42 21.378 384165 0.62 .alpha.-tocospiro b 43 21.626 175973 0.28 Eicosyl heptafluorobutyrate 44 21.803 89987 0.14 Hexacosanoic acid, methyl ester 45 22.769 160960 0.26 .gamma.-tocopherol 46 22.989 86757 0.14 Tetracontane 47 23.174 92442 0.15 Stigmast-5-en-3-ol, (3.beta.)- 48 23.380 1030143 1.65 Vitamin e 49 25.372 1237263 1.98 .gamma.-sitosterol 50 27.084 183826 0.29 Di-o-acetyltetrahydrostapelogenin Table 4. Docking results of 81 phytoligands.

S. no. Name of the ligand Binding free energy

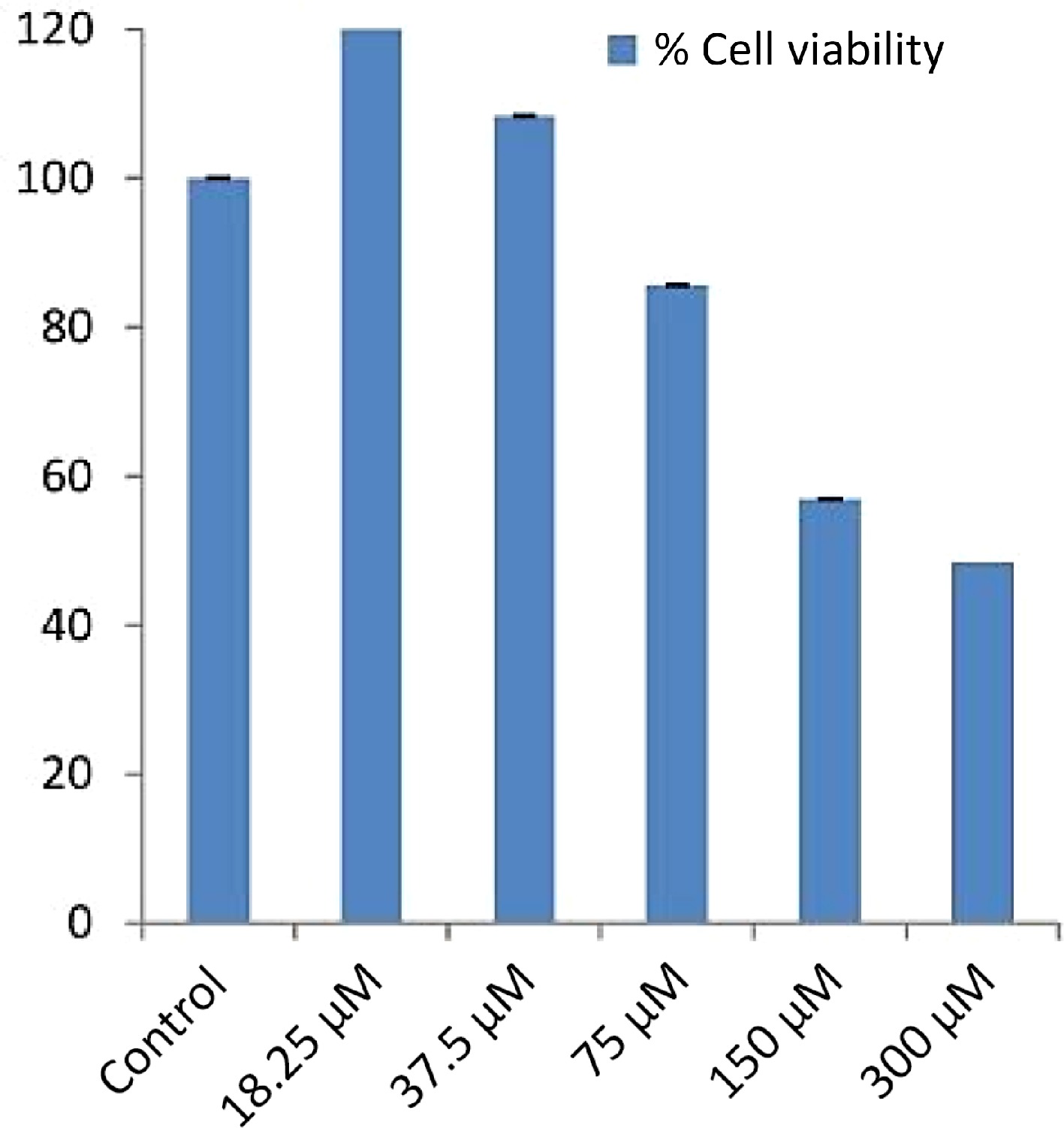

(kcal/mol)pKi Ligand efficieny (kcal/mo/non-H atom) Torsional energy 1 Phenol, 2-methoxy-4-(2-propenyl)- –5.6 4.11 0.4667 1.2452 2 Cyclododecane –5.9 4.33 0.4917 0 3 Bicyclo[7.2.0]undec-4-ene,4,11,11-trimethyl-8-methylene- –6.6 4.84 0.44 0 4 1,4,8-Cycloundecatriene, 2,6,6,9-tetramethyl-,(e,e,e)- –6.5 4.77 0.4333 0 5 Phenol, 3,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- –6.5 4.77 0.4333 0.9339 6 1-Heptadecene –4.6 3.37 0.2706 4.3582 7 1-Octadecene –4 2.93 0.2 4.0469 8 Neophytadiene –5.9 4.33 0.295 4.0469 9 2-Pentadecanone, 6,10,14-trimethyl- –5.4 3.96 0.2842 3.7356 10 7,9-Di-tert-butyl-1-oxaspiro(4,5)deca-6,9-diene-2,8-dione –6.5 4.77 0.325 0.6226 11 Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester –4.9 3.59 0.2579 4.6695 12 Isophytol –4.9 3.59 0.2333 4.3582 13 Dibutyl phthalate –5.2 3.81 0.26 3.113 14 1-Nonadecene –4.9 3.59 0.2579 4.9808 15 1-octadecanol –5 3.67 0.2632 5.2921 16 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (z,z)-, methyl ester –5 3.67 0.2381 4.6695 17 9,12,15-Octadecatrienoic acid, methyl ester, (z,z,z)- –5.4 3.96 0.2571 4.3582 18 P-Menth-1-ene-3,3-d2 –4.9 3.59 0.49 0.3113 19 Behenic alcohol –4.7 3.45 0.2043 6.5373 20 Glycidyl palmitate –5.4 3.96 0.2842 3.7356 21 4,8,12,16-Tetramethylheptadecan-4-olide –6.3 4.62 0.2739 3.7356 22 N-tetracosanol-1 –4.4 3.23 0.176 7.1599 23 Glycidyl oleate –4.6 3.37 0.1917 5.6034 24 Pentacosane –4.7 3.45 0.188 6.8486 25 Hexadecanoic acid, 2-hydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethyl ester –4.6 3.37 0.2 6.226 26 1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid –5.7 4.18 0.475 1.2452 27 Carbonic acid, propyl 3,5-difluophenyl ester –6.1 4.47 0.4067 1.5565 28 9-Octadecenoic acid (z)-, 2,3-dihydroxypropyl ester –5 3.67 0.2 6.5373 29 Octadecanoic acid, 2,3-dihydroxypropyl ester –4.9 3.59 0.196 6.8486 30 Carbonic acid, eicosyl prop-1-en-2-yl ester –5.1 3.74 0.1889 6.8486 31 Tetracosane –4.9 3.59 0.2042 6.5373 32 1-Heptacosanol –5.1 3.74 0.1821 8.0938 33 Triacontyl acetate –3.9 2.86 0.1147 9.339 34 Gamma.-tocopherol –6.8 4.99 0.2267 4.0469 35 Octacosanol –4.2 3.08 0.1448 8.4051 36 2,5,7,8-Tetramethyl-2-(4,8,12-trimethyltridecyl)-3,4-dihydro-2h-chromen-6-yl hexofuranoside –7.2 5.28 0.1714 6.226 37 Ergost-5-en-3-ol –7.3 5.35 0.2517 1.8678 38 2,6,10,15,19,23-Hexamethyl-tetracosa-2,10,14,18,22-pentaene-6,7-diol –6 4.4 0.1875 5.6034 39 Gamma.-sitosterol –9 6.6 0.3 2.1791 40 4h-pyran-4-one,2,3-dihydro-3,5-dihydroxy-6-methyl- –5 3.67 0.5 0.6226 41 1,5-Dimethyl-1-vinyl-4-hexenyl 2-aminobenzoate –6.4 4.69 0.32 2.4904 42 E-6-octadecen-1-ol acetate –4.7 3.45 0.2136 5.2921 43 4-Hydroxy-3-methylacetophenone –5.7 4.18 0.5182 0.6226 44 1-undecanol –4.5 3.3 0.375 3.113 45 Methyl2,3,6,7-tetra-o-acetyl-4-o-methyl-.beta.-glycero-d-glucoheptopyranoside –5.5 4.03 0.1964 3.7356 46 Guanosine –6.8 4.99 0.2615 1.5565 47 1,3:2,5-Dimethylene-l-rhamnitol –5.4 3.96 0.4154 0.3113 48 Octadecanoic acid –5.3 3.89 0.265 5.2921 49 1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid, diethyl este –5.4 3.96 0.3375 1.8678 50 .alpha.-methyl-l-sorboside –4.7 3.45 0.3615 1.8678 51 .alpha.-d-galactopyranoside, methyl –5.2 3.81 0.4 1.8678 52 Butanoic acid, 3-methyl-, hexahydro-4- methylspiro[cyclopenta[c]pyran-7(1h),2'-oxirane]-1,6-diyl ester –6.8 4.99 0.2267 3.4243 53 Tricyclo[7.2.0.0(2,6)]undecan-5-ol, 2,6,10,10-tetramethyl- (isomer 3) –6.5 4.77 0.4062 0.3113 54 .alpha.-d-galactopyranoside, methyl –5.3 3.89 0.4077 1.8678 55 Octadecanoic acid, methyl ester –4.1 3.01 0.1952 5.2921 56 2(4h)-benzofuranone, 5,6,7,7a-tetrahydro-6- hydroxy-4,4,7a-trimethyl-, (6s-cis)- –6.5 4.77 0.4643 0.3113 57 Neophytadiene –5 3.67 0.25 4.0469 58 Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester –4.9 3.59 0.2579 4.6695 59 1-Hexadecen-3-ol, 3,5,11,15-tetramethyl- –5.7 4.18 0.2714 4.3582 60 Pentadecanoic acid, methyl ester –4.4 3.23 0.2444 4.3582 61 9,12-Octadecadienoic acid (z,z)-, methyl ester –5.4 3.96 0.2571 4.6695 62 (9e,12e)-9,12-octadecadienoyl chloride # –4.7 3.45 0.235 4.3582 63 1,1'-bicyclohexyl, 2-methyl-, cis- –5.6 4.11 0.4308 0.3113 64 Methyl stearate –5 3.67 0.2381 5.2921 65 Cholest-24-ene, (5.alpha.,20.xi.)- –9.2 6.75 0.3407 1.2452 66 Methyl octadeca-9,12-dienoate –4.5 3.3 0.2143 4.6695 67 Methyl 4-(dimethylamino)bicyclo[2.2.2]oct- 5-ene-2-carboxylate –5.7 4.18 0.38 0.9339 68 Hexadecanoic acid, 2-hydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethyl ester –4.8 3.52 0.2087 6.226 69 17-octadecynoic acid –5.1 3.74 0.255 5.2921 70 Eicosanoic acid, methyl ester –4.8 3.52 0.2087 5.9147 71 Undec-10-ynoic acid, undec-2-en-1-yl ester –5.1 3.74 0.2125 5.9147 72 Hexadecanoic acid, 2-hydroxy-1-(hydroxymethyl)ethyl ester –4.7 3.45 0.2043 6.226 73 Hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester –4.5 3.3 0.2368 4.6695 74 Oleoyl chloride –4.6 3.37 0.23 4.6695 75 Octadecanoic acid, 2,3-dihydroxypropyl ester –4.6 3.37 0.184 6.8486 76 9-octadecenamide –4.7 3.45 0.235 4.6695 77 .alpha.-tocospiro b –6.4 4.69 0.1939 4.3582 78 Eicosyl heptafluorobutyrate –5.6 4.11 0.1697 7.1599 79 Hexacosanoic acid, methyl ester –4.7 3.45 0.1621 7.7825 80 Stigmast-5-en-3-ol, (3.beta.)- –7.6 5.57 0.2533 2.1791 81 Vitamin e –7.1 5.21 0.229 4.0469 82 Plumbagin –5.9 4.33 0.4214 0.3113 83 Sanguinarine –8.9 6.53 0.356 0 The absorption of drugs by the body is related to their pharmacokinetic properties and also cellular toxicity. The potency of the drug depends mostly on the pharmacokinetic parameters because ADME processes command the rate and extent of absorption when an administered dose of a drug approaches to its action site. Hence, in silico pharmacokinetic profile of filtered compounds was surveyed to gather the putative bioavailability data for receptor 6NJS. The cumulative findings for pharmacokinetics profiling, bioavailability data, drug-likeness properties and drug friendliness and toxicity effects of selected 26 phytoligands with known inhibitors (Plumbagin and Sanguinarine) are given in Tables 5−10. The prediction revealed that the six molecules (EG-9, EG-12, EG-13, EG-16, and EG-26) can be lead compounds for new drug candidates for anti-cancer phytomedicine. The Half maximal Inhibitory concentration of EG-13 was (IC50 = 254.29 µg/ml) further support our results (Fig. 3).

Table 5. Pharmacokinetics prediction of phytoligands established in E. ganitrus.

S. no. Phytochemical Gastro- intestinal absorption Blood-brain permeant P-glycoprotein substrate CYP450 1A2 inhibitor CYP450 2C19 inhibitor CYP450 2C9 inhibitor CYP450 2D6 inhibitor CYP450 3A4 inhibitor Skin permeation as log Kp (cm/s) EG-1 Cholest-24-ene, (5.alpha.,20.xi.)- Low No No No No Yes No No –1.02 EG-2 gamma.-sitosterol Low No No No No No No No –2.65 EG-3 Stigmast-5-en-3-ol, (3.beta.)- Low No No No No No No No –2.20 EG-4 Ergost-5-en-3-ol Low No No No No No No No –2.50 EG-5 2,5,7,8-Tetramethyl-2-(4,8,12-trimethyltridecyl)-3,4-dihydro-2h-chromen-6-yl hexofuranoside Low No No No No No No Yes –3.60 EG-6 Vitamin e Low No Yes No No No No No –1.33 EG-7 Guanosine Low No No No No No No No –9.37 EG-8 gamma.-tocopherol Low No Yes No No No No No –1.51 EG-9 Butanoic acid, 3-methyl-, hexahydro-4- methylspiro[cyclopenta[c]pyran-7(1h),2'-oxirane]-1,6-diyl ester High Yes No No No No Yes Yes –6.18 EG-10 Bicyclo[7.2.0]undec-4-ene,4,11,11-trimethyl-8-methylene- Low No No No Yes Yes No No –4.44 EG-11 1,4,8-Cycloundecatriene, 2,6,6,9-tetramethyl-,(e,e,e)- Low No No No No Yes No No –4.32 EG-12 Phenol, 3,5-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)- High Yes No No No No Yes No –4.07 EG-13 7,9-Di-tert-butyl-1-oxaspiro(4,5)deca-6,9-diene-2,8-dione High Yes No No Yes Yes No No –5.28 EG-14 2(4h)-benzofuranone, 5,6,7,7a-tetrahydro-6- hydroxy-4,4,7a-trimethyl-, (6s-cis)- High Yes No No No No No No –6.79 EG-15 Tricyclo[7.2.0.0(2,6)]undecan-5-ol, 2,6,10,10-tetramethyl- (isomer 3) High Yes No No Yes Yes No No –4.75 EG-16 1,5-Dimethyl-1-vinyl-4-hexenyl 2-aminobenzoate High Yes No No Yes Yes No No –4.54 EG-17 alpha.-tocospiro b High No No No No No No No –3.90 EG-18 4,8,12,16-Tetramethylheptadecan-4-olide Low No No Yes No Yes No No –2.70 EG-19 Carbonic acid, propyl 3,5-difluophenyl ester High Yes No Yes Yes No No No –5.37 EG-20 2,6,10,15,19,23-Hexamethyl-tetracosa-2,10,14,18,22-pentaene-6,7-diol Low No No Yes No Yes No No –2.37 EG-21 Cyclododecane Low No No No No No No No –4.42 EG-22 Neophytadiene Low No Yes No No Yes No No –1.17 EG-23 1,2-Benzenedicarboxylic acid High No No No No No No No –6.80 EG-24 4-Hydroxy-3-methylacetophenone High Yes No Yes No No No No –6.54 EG-25 1-Hexadecen-3-ol, 3,5,11,15-tetramethyl- Low No Yes No No Yes No No –2.41 EG-26 Methyl 4-(dimethylamino)bicyclo[2.2.2]oct- 5-ene-2-carboxylate High Yes No No No No No No –6.65 Plumbagin High Yes No Yes No No No No –5.82 Sanguinarine High Yes Yes Yes Yes No No No –5.17 Table 6. Bioavailability prediction of phytoligands established in E. ganitrus.

Phyto-ligands Bioavailability score Water solubility as logS iLOGP XLOGP3 WLOGP MLOGP SILICOS-IT EG-1 0.55 Poorly soluble as –6.25 5.12 10.62 8.42 8.32 7.14 EG-2 0.55 Poorly soluble as –6.19 4.75 8.86 7.96 5.80 7.04 EG-3 0.55 Poorly soluble as –6.19 4.79 9.34 8.02 6.73 7.04 EG-4 0.55 Moderately soluble as –5.79 4.92 8.80 7.63 6.54 6.63 EG-5 0.55 Poorly soluble as –7.37 6.14 8.89 6.31 3.49 8.12 EG-6 0.55 Poorly soluble as –9.16 5.92 10.70 8.84 6.14 9.75 EG-7 0.55 Very Soluble as 0.51 –0.23 –1.89 –3.00 –2.76 –2.22 EG-8 0.55 Poorly soluble as –8.79 5.76 10.33 8.53 5.94 9.20 EG-9 0.55 Soluble as –2.86 3.87 3.34 2.93 2.07 3.34 EG-10 0.55 Soluble as –3.77 3.29 4.38 4.73 4.63 4.19 EG-11 0.55 Soluble as –3.52 3.27 4.55 5.04 4.53 3.91 EG-12 0.55 Soluble as –4.25 2.86 4.91 3.99 3.87 3.81 EG-13 0.55 Soluble as –3.81 2.91 3.81 3.59 2.87 3.82 EG-14 0.55 Very Soluble as –1.82 1.88 1.00 1.41 1.49 1.86 EG-15 0.55 Soluble as –3.18 3.01 4.09 3.61 3.81 3.40 EG-16 0.55 Moderately soluble as –4.28 3.37 4.83 4.12 3.63 3.75 EG-17 0.55 Poorly soluble as –7.19 4.94 7.24 6.58 3.67 7.85 EG-18 0.55 Poorly soluble as –6.31 4.15 7.86 6.52 4.96 6.99 EG-19 0.55 Soluble as –3.59 2.84 3.17 3.73 2.91 2.81 EG-20 0.55 Poorly soluble as –6.30 6.11 9.38 8.77 6.01 9.10 EG-21 0.55 Soluble as –3.21 3.01 4.10 4.68 5.00 4.00 EG-22 0.55 Poorly soluble as –6.11 5.05 9.62 7.17 6.21 7.30 EG-23 0.85 Soluble as –1.14 0.60 0.73 1.08 1.20 0.61 EG-24 0.55 Very Soluble as –2.53 1.54 0.95 1.90 1.44 2.14 EG-25 0.55 Moderately soluble as –5.51 4.97 8.02 6.36 5.25 6.57 EG-26 0.55 Very Soluble as –1.35 2.70 1.31 1.45 1.77 1.11 Plumbagin 0.55 Soluble as –2.85 1.79 2.29 1.72 0.59 2.22 Sanguinarine 0.55 Poorly soluble as –6.09 –0.04 4.45 3.43 2.72 3.85 Table 7. Drug-likeness prediction of phytoligands established in E. ganitrus.

Phyto-ligands Lipinski

ruleGhose

filterVeber

filterEgan

filterMuegge

filterEG-1 Yes No Yes No No EG-2 Yes No Yes No No EG-3 Yes No Yes No No EG-4 Yes No Yes No No EG-5 Yes No No No No EG-6 Yes No No No No EG-7 Yes No No No No EG-8 Yes No No No No EG-9 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes EG-10 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes EG-11 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes EG-12 Yes Yes Yes Yes No EG-13 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes EG-14 Yes Yes Yes Yes No EG-15 Yes Yes Yes Yes No EG-16 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes EG-17 Yes No No No No EG-18 Yes No No No No EG-19 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes EG-20 Yes No No No No EG-21 Yes Yes Yes Yes No EG-22 Yes No No No No EG-23 Yes No Yes Yes No EG-24 Yes No Yes Yes No EG-25 Yes No No No No EG-26 Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Plumbagin Yes Yes Yes Yes No Sanguinarine Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Table 8. Medicinal chemistry prediction of phytoligands established in E. ganitrus.

SI. No. PAINS structural alert Brenk structural alert Lead-

likenessSynthetic accessibility score EG-1 0 1 2 5.61 EG-2 0 1 2 6.42 EG-3 0 1 2 6.30 EG-4 0 1 2 6.17 EG-5 0 0 3 7.10 EG-6 0 0 3 5.17 EG-7 0 0 0 3.86 EG-8 0 0 3 5.00 EG-9 0 2 2 5.59 EG-10 0 1 2 4.51 EG-11 0 1 2 3.66 EG-12 0 0 2 1.37 EG-13 0 0 1 4.35 EG-14 0 0 1 3.63 EG-15 0 0 2 3.77 EG-16 0 2 1 2.91 EG-17 0 0 3 6.76 EG-18 0 0 2 4.12 EG-19 0 1 1 2.23 EG-20 0 1 3 5.52 EG-21 0 0 2 2.21 EG-22 0 1 2 4.08 EG-23 0 0 1 1.00 EG-24 0 0 1 1.00 EG-25 0 1 2 3.89 EG-26 0 1 1 4.38 Plumbagin 2 0 1 2.41 Sanguinarine 0 2 1 2.59 Table 9. Toxicity prediction of phytoligands established in E. ganitrus.

Phyto-ligands LD50 (mg/kg) Toxicity class Hepatotoxicity Carcinogenicity Immunotoxicity Mutagenicity Cytotoxicity EG-1 5000 5 Inactive Inactive Active Inactive Inactive EG-2 890 4 Inactive Inactive Active Inactive Inactive EG-3 890 4 Inactive Inactive Active Inactive Inactive EG-4 890 4 Inactive Inactive Active Inactive Inactive EG-5 3000 5 Inactive Inactive Active Inactive Inactive EG-6 5000 5 Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive EG-7 13 2 Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive EG-8 5000 5 Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive EG-9 8000 6 Inactive Active Inactive Active Inactive EG-10 5300 5 Inactive Inactive Active Inactive Inactive EG-11 3650 5 Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive EG-12 800 4 Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive EG-13 900 4 Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive EG-14 34 2 Inactive Active Inactive Inactive Inactive EG-15 2050 5 Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive EG-16 4250 5 Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive EG-17 300 3 Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive Active EG-18 4400 5 Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive EG-19 1500 4 Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive EG-20 4300 5 Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive EG-21 750 3 Inactive Active Inactive Inactive Inactive EG-22 5050 6 Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive EG-23 2530 5 Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive EG-24 2830 5 Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive EG-25 340 4 Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive EG-26 2000 4 Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive Inactive Plumbagin 16 2 Inactive Active Inactive Active Inactive Sanguinarine 778 4 Inactive Active Active Active Inactive Table 10. Bioavailability prediction of phytoligands established in E. ganitrus.

Phyto-ligand Lipophilicity

(XLOGP3)Size

(MW g/mol)Polarity

(TPSA)Insolubility

[Log S (ESOL)]Insaturation

(Fraction Csp3)Flexibility

(Num. rotatable bonds)EG-9 3.34 368.46 74.36 –3.70 0.90 8 EG-12 4.91 206.32 20.23 –4.38 0.57 2 EG-13 3.81 276.37 43.37 –3.82 0.65 2 EG-15 4.09 222.37 20.23 –3.80 1.00 0 EG-16 4.83 273.37 52.32 –4.34 0.35 7 EG-26 1.31 209.28 29.54 –1.76 0.75 3 Plumbagin 2.29 188.18 54.37 –2.77 0.09 0 Sanguinarine 4.45 332.33 40.80 –5.24 0.15 0

Figure 3.

IC50 values of EG-13 phytochemical of E. ganitrus leaves against human cancer cell lines HeLa.

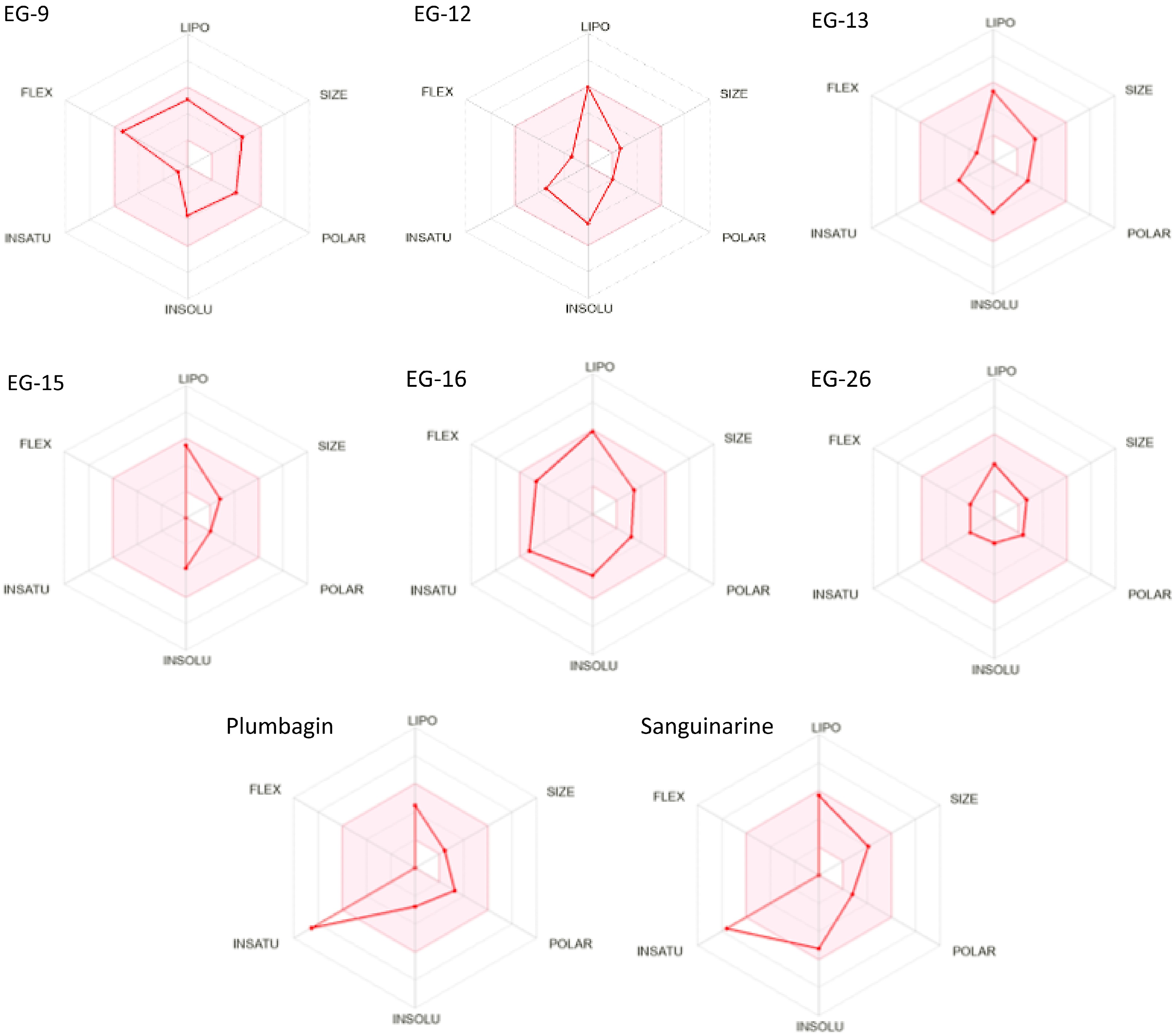

In Table 5, for pharmacokinetics prognostication, the gastrointestinal (GI) absorption rate was fetched for all preferred six phytoligands and both reference drugs. The blood-brain permeability was seen as positive for all the six phytoligands and both reference drugs. The prediction of bioavailability (Table 6) demonstrated that similar bioavailability scores were observed for all the filtered six phytoligands (0.55) like reference drugs. The water solubility data showed all the six compounds and plumbagin are soluble while Sanguinarine is poorly soluble. For drug-likeness prediction (Table 7), all the six compounds and both known inhibitors were obtained suitable for the Lipinski rule as zero violation. For Ghose, Veber, and Egan filter 0 violation was obtained for all the six phytoligands and both inhibitors. In the case of medicinal chemistry friendliness prediction (Table 8), the PAINS structural alert obtained 0 violations for all the six phytoligands and sanguinarine while two alerts for plumbagin. Table 9 shows EG-9 belongs to the non-toxic class VI, EG-15, and EG-16 also belong to the non-toxic class V, EG-12, EG-13, EG-26 and Sanguinarine belongs to the less toxic class IV while plumbagin belongs to the high-toxic class II. The bioavailability radar (Fig. 3) for phytoligands depicting bioavailability prognostic showed that all six phytoligands were found within the data range of lipophility nature (−0.7 < XLOGP3 < +5.0), molecule size (150 g/mol < MW < 500g/mol), polarity (20 Ų < TPSA < 130Ų), insolubility [−6 < LogS (ESOL) < 0], insaturation (0.25 < Fraction Csp3 < 1) and flexible bonds (0 < Num. rotatable bonds < 9) and colored part of radar while known inhibitors plumbagin and sanguinarine does not fit the bioavailability radar (Table 10). As mentioned in Table 5, all the phytoligands and reference compounds have higher gastrointestinal (GI) absorption rates, therefore they can instantly be absorbed by the human intestine. All phytoligands have the ability to pass the blood brain barrier (BBB permeant) and values for the aqueous solubility (log S) of the phytochemicals fall in the recommended range that is −1 to −5[29], thus, have improved absorption and distribution properties. The bioavailability scores were identical for all six molecules, standing at 0.55, similar to the reference drugs. In drug-likeness prediction, none of the six compounds and both known inhibitors violated the Lipinski rule, Ghose, Veber, and Egan filters. Regarding medicinal chemistry friendliness, the PAINS structural alert identified zero violations for all six phytoligands and Sanguinarine, whereas Plumbagin had two alerts. Table 9 revealed that EG-9 belonged to the non-toxic class VI, while EG-15 and EG-16 were in harmless class V. Other compounds EG-12, EG-13, EG-26 and sanguinarine was from less harmful class IV which could be modified to a non-toxic class during the lead optimization stage of drug discovery[30] while selected standard plumbagin showed high toxic class II. Drug-induced hepatotoxicity often lead to abrupt liver failure and drug rejections[31]. Drug-induced liver injury might be long-term or occur only once. Obviously, the selected compounds and standards are non-hepatotoxic. The bioavailability radar (Fig. 4) depicted that all six phytoligands were within the data range for oral bioavailability prediction. Conversely, standards plumbagin and sanguinarine did not fit within the bioavailability radar. The pink area shown in the radar corresponds to the most promising zone for all the bioavailability properties. In Table 10, all the phytochemicals satisfied 150 g/mol and 500 g/mol criteria for (SIZE) of good drug candidates. The polarity (POLAR) was observed with the Total Polarity Surface Area (TPSA) and all the phytochemicals show good TPSA values. Besides, the flexibility (FLEX) property evaluated by the number of rotatable bonds falls within the recommended range. Lipophilicity (LIPO) and insolubility (INSOLU) were evaluated and come in the range The Unsaturation (INSATU) was calculated using Fraction Csp3 falls within a recommended range of 0.25 < Fraction Csp3 < 1) for all phytoligands. However, Plumbagin and Sanguinarine exhibit lower values (0.09 and 0.15, respectively).

Figure 4.

Bioavailability radar (pink area exhibits optimal range of particular property) for leading phytocompounds molecules. LIPO = lipophilicity as XLOGP3, SIZE = size as molecular weight, POLAR = polarity as TPSA (topological polar surface area), INSOLU = insolubility in water by log S scale, INSATU = insaturation as per fraction of carbons in the sp3 hybridization, and FLEX = flexibility as per rotatable bonds.

2D and 3D interactions of the five phytoligands (EG-9, EG-12, EG-13, EG-15, EG-16 and EG-26) with 6njs are shown in Table 11. EG-9 divulged two assenting hydrogen bond interactions at the active site having amino acids of Glu96 and Lys97. In additon to that a non-classical C-H bond Vander Waals interaction was also noticed at the active site involving Arg93 residue and alkyl and pi-alkyl interactions were observed at Leu525 and Trp501 respectively. In EG-12 a conventional hydrogen bond interaction was observed at Asn538, a pi-pi T-shaped, two alkyl and a pi-alkyl interactions were observed at Tyr539, Ile522, Trp501 and Leu525 respectively. EG-13 showed one favorable hydrogen bond interaction and two hydrophobic alkyl interactions at the active site with the residue of Glu96, Leu95 and Lys97 respectively. EG-15 showed two alkyl and two pi-alkyl interactions at the active site of the residues of Leu95, Ile522, Trp501 and Tyr539 respectively. In EG-16 two conventional hydrogen bonds were observed at Leu731 and Thr716. EG-26 formed three favorable hydrogen bonds with Asp369, Asp370 and Asp371 at the active site of the receptor. Plumbagin showed a conventional hydrogen bond interaction, a pi-pi T-shaped and a carbon-hydrogen bond interaction at Tyr539, Trp501 and Ser540 respectively. Sanguinarine showed a carbon hydrogen bond, a pi-sigma, a alkyl, and a pi-alkyl interaction at the site of Glu696, Leu731, Pro769 and Pro695 respectively (Table 11). Previously it has been shown that residue at 97 could have amprospective ubiquitin acceptor position in STAT3 NH2 terminal domain, suggesting lysine amino acid may have a significant role and location in a sumolation/ubiquitination consensus sequence[32]. The majority of phytoligand interactions exist in the Linker domain and Transactivation domain of the STAT3.

Table 11. 2D and 3D binding interactions between the receptor 6NJS and molecules.

Phyto-ligands 2D- Binding interaction 3D- Binding interaction EG-9 (-6.8)

EG-12 (-6.5)

EG-13 (-6.5)

EG-15 (-6.5)

EG-16 (-6.4)

EG-26

(-5.7)

Plumbagin

Sanguinarine

-

All the six compounds (EG-9, EG-12, EG-13, EG-15, EG-16 and EG-26) significantly bind with STAT3. The phytochemicals epitomized good in silico results as reflected by their promising binding affinity, considerable inhibitory constant with optimum protein-ligand stabilization energy. Consecutively, binding signifies that phytoligands interact with STAT3 by the NH2 terminal and boosts its transcriptional activity and interferes with the cellular proliferation process and apoptosis[32]. Bioavailability radar and toxicological profiles of the preferred phytoligands revealed that these compounds compel to have ample drug likeliness properties. Moreover, EG-9, EG-13, EG-15, EG-16 and EG-26 have not been explored for their anticancer potential and can be derivatized or have the probability of being used as lead compounds.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study design and draft manuscript preparation (equal): Mehnaj, Bhat AR, Athar F; supervision: Athar F; experimentation and writing of manuscript: Mehnaj; characterization and editing: Bhat AR. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

This study involved the use of established human cell lines. The cell lines used in this research were obtained from the National Centre for Cell Sciences (NCCS), Pune, India and were used in accordance with institutional and national ethical standards. The cell lines have been previously published or validated, and no new human tissues were used in this study.

-

The supplementary data will be made available by the authors to all upon reasonable request.

-

Miss Mehnaj is grateful to UGC for obtaining the non-NET fellowship allowing completion of this work.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2024 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Mehnaj, Bhat AR, Athar F. 2024. In silico exploration of Elaeocarpus ganitrus extract phytochemicals on STAT3, to assess their anticancer potential. Medicinal Plant Biology 3: e009 doi: 10.48130/mpb-0024-0010

In silico exploration of Elaeocarpus ganitrus extract phytochemicals on STAT3, to assess their anticancer potential

- Received: 08 December 2023

- Revised: 25 March 2024

- Accepted: 18 April 2024

- Published online: 16 May 2024

Abstract: Elaeocarpus ganitrus Rox of the Elaeocarpaceae family is a broad-leaved medicinal plant and exhaustively used in orthodox systems of treating diseases. However, its anticancer impact and propensity to STAT3 has not yet been analyzed. The plant's extracts were in vitro assayed on the HeLa cell line and subsequently, GC-MS chromatogram of the methanolic, and chloroform extracts of the plant revealed that 106 compounds were present in the extracts. Subsequent filtration using Lipinski rules resulted in 81 phytochemicals being selected for the docking process with pre-selected receptor STAT3 (6NJS). Twenty-six out of 81 phyto-ligands showed high binding energy. Many drugs have weak pharmacokinetic properties and cellular toxicity and consequently, cannot pass through clinical trials. Hence, it is essential to determine the pharmacokinetic parameters of the phytoligands showing preferred binding with receptor 6NJS to consider the apparent bioavailability. The data for pharmacokinetics behavior, bioavailability extent, drug-likeness properties, medicinal chemistry friendliness, and toxicity of 26 phytochemicals with referenced inhibitors was explored. These 26 compounds were further checked for their ADMET properties by using the swissADME and PROTOX-II web server with the known inhibitors plumbagin and sanguinarine to determine the lead phytocompounds. The predictions of ADMET properties obtained six suitable phytocompounds (EG-9, EG-12, EG-13, EG-15, EG-16 and EG-26) of E. ganitrus, and found to be a perfect fit in the bioavailability radar. 2D and 3D interaction of phytoligands with the STAT3 show that the binding is through lys97, suggesting NH2-terminal domain binding of STAT3 with ligands which is the main mono-ubiquitin conjugation spot. Most of the phytoligands interactions exist in the Linker domain and Transactivation domain of the STAT3.

-

Key words:

- Phytochemicals /

- STAT3 /

- Binding energy /

- Bioavailability