-

As an essential component of proteins and nucleotides in plants, nitrogen (N) constitutes a critical mineral nutrient, the availability of which significantly influences plant growth and yield. A lack of N severely restricts the synthesis of N-containing compounds, including proteins and chlorophyll, resulting in stunted growth, narrow leaves, reduced photosynthesis, and yield, and reduced plant defenses against a variety of diseases[1]. Previous studies have shown that nitrate (NO3−) deficiency inhibits the conversion of the chlorophyll precursor 5-aminobilinic acid (ALA) to porphobilinogen (PBG) in apple leaves, thereby reducing chlorophyll concentration[2]. N deficiency also promotes leaf senescence in apple through the ABA signaling pathway, reducing the time period of photosynthesis and carbon assimilation[3]. To seek additional N sources in a low-N environment, sugar metabolism in apple roots is enhanced, with a large proportion of photosynthetic products transported to the roots to support rapid root growth, resulting in slower shoot growth[4]. The inhibition of vegetative growth in apple under low-N stress ultimately leads to reduced yield and fruit weight. Kühn et al.[5] found that low N supply (14 mg N·L−1) significantly reduced shoot growth, total yield, and fruit size in the apple cultivar 'Pigeon'. Due to the insufficient soil organic matter in Chinese orchards, growers have been compelled to use excessive inorganic N fertilizers to achieve high yields and large fruits[6]. This surplus N reduces nitrogen use efficiency (NUE) and fruit quality and triggers significant environmental issues[7]. However, the blind reduction of N application inevitably leads to decreased yields and economic losses. Therefore, improving fertilization strategies and techniques to enhance the adaptability of apple trees to low-N conditions and increase NUE is crucial for reducing N inputs and promoting the sustainable development of the apple industry.

A multitude of research studies have demonstrated that hormones are potential regulatory factors in modulating plant adaptation to low-N stress[8]. Gibberellin (GA) is a tetracyclic diterpene phytohormone that promotes plant growth by reducing the accumulation of growth-inhibitory DELLA proteins[9]. The recognition and signaling pathways of GA are of great importance in the response of plants to a variety of abiotic stresses, including cold, salt, and osmotic stress[10]. The available evidence suggests that GAs, as growth regulators, are closely associated with the absorption, transport, and utilization of N[11,12]. When exposed to a low-N environment, the GA content in Polygonum cuspidatum leaves decreases significantly[13]. In maize, GA synthesis-deficient mutants show a reduced uptake of NO3− and exhibit higher sensitivity to low N stress[14]. In recent years, many studies have demonstrated crosstalk between GA and nitrate (NO3−) signaling. The NO3−-NLP7 signaling pathway (where NLP7 is a key regulator of the primary NO3− response) can regulate the expression of the GA metabolism gene GA3ox1, promoting the conversion of GA9 (biologically inactive) to GA4 (biologically active), thereby reducing DELLA accumulation and accelerating plant growth[15]. There is also evidence that NO3− signaling mediated by the NO3− receptor NRT1.1 regulates the expression of the flowering repressors SMZ/SNZ through the GA-DELLA pathway, thereby controlling flowering time in Arabidopsis thaliana[16]. In addition, GA can provide feedback on the regulation of N metabolism. Wu et al.[17] found that NGR5 (NITROGENMEDIATED TILLER GROWTH RESPONSE 5) responds to high N input and promotes tillering in rice. The degradation of NGR5 depends on the interaction between GA and its receptor GID1, following the same degradation mechanism as DELLA. Additionally, DELLA accumulation inhibits the formation of a complex between GRF4 (GROWTH-REGULATING FACTOR 4) and its interacting partner GIF1 in rice[12]. This complex binds to the promoter sequences of genes involved in N assimilation and drives their expression.

It is well known that the processes of N and C metabolism must be closely coordinated to sustain optimal growth and development of plants. As in most other terrestrial plants, NO3− serves as the main form of inorganic N absorbed and employed by apple trees[18]. NO3− is absorbed and transported through NO3− transporters (NRTs), and its assimilation in plants is facilitated by a range of enzymes related to N metabolism. NO3− assimilation requires a substantial input of reducing equivalents, C skeletons, and ATP provided by photosynthesis, while N metabolism provides photosynthetic pigments and enzymes for photosynthesis[19]. Low N stress decreases stomatal conductance, chlorophyll levels, and RuBisCO content, thus reducing the photosynthetic rate[20−22]. In crabapple plants, carbohydrate metabolism, and transport respond to changes in the N supply levels[23]. Conversely, sugars can regulate NO3− uptake, assimilation, and translocation as signals and nutrients. For example, in Arabidopsis plants, sucrose regulates NO3− reductase (NR) activity through the trehalose 6-phosphate pathway, thereby affecting NO3− assimilation[24]. In addition, the expression of NRT2.1, which is involved in NO3− absorption, was also regulated by the plant's C status[25]. Although there is evidence that GA is a regulator of N metabolism, most studies have ignored the interaction of C and N under the influence of GA. Therefore, this study analyzed the effects of exogenous GA3 on the morphological traits, C-N metabolism and allocation, and the energy status of apple rootstock seedlings under low-N stress. This study aims to investigate the impact of exogenous GA3 in mitigating low-N stress and the associated underlying mechanisms, providing new insights for improving the efficient use of N fertilizers in apple cultivation.

-

The plant material used in this experiment was apple dwarfing rootstock M26 seedlings. Rootstock seedlings with uniform growth (five true leaves) were secured onto foam plates, each with 15 holes (one plant per hole), and cultured in plastic containers (34 cm × 25 cm × 12 cm) filled with 7 L of nutrient solution. The seedlings were placed in a 50% Hoagland solution for 5 d, then transferred to a 100% solution for 7 d to acclimatize them to the hydroponic environment. To maintain a pH of 6.0 ± 0.1, HCl or NaOH was added to the nutrient solution. The nutrient solution was changed every 3 d, and aeration was provided for 12 h·d–1. All plants were cultivated in a growth chamber with natural light, at a temperature of 18–28 °C during the day and 10–15 °C at night, with a relative humidity of 65%.

There were four treatments in the formal trial: normal N supply + spraying of water (NN), low N supply + spraying of water (LN), low N supply + spraying of GA3 (LN + GA), and low N supply + spraying of paclobutrazol (PAC) (LN + PAC). PAC inhibits gibberellin synthesis. Each treatment contained three pots of seedlings. The N supply level was regulated by NO3−, and the NO3− concentrations of normal N supply and low N supply were 5 and 0.5 mM, respectively. The NO3− present in the nutrient solution was derived from Ca(15NO3)2 and Ca(NO3)2. CaCl2 was used to equalize the Ca2+ concentrations among treatments, and K2SO4 was used to supplement the nutrient solution with K+. The nutrient solution also included the following other nutrients: 2.5 mM K2SO4, 1 mM KH2PO4, 2 mM MgSO4, 0.1 mM EDTA-Fe, 9 μM MnCl2·4H2O, 37 μM H3BO4, 0.7 μM ZnSO4·7H2O, 0.5 μM H2MoO4·H2O, and 0.3 μM CuSO4·5H2O. In addition, the spraying concentrations of GA3 and PAC were both 50 mg·L−1, with an application interval of 3 d. The formal experiment lasted for 25 d until sampling.

13C and 15N labeling methods and isotope analysis

-

Once the formal trial began, 0.375 g of Ca(15NO3)2 (with an abundance of 10.14%) was added to each nutrient solution during every solution change for 15N labeling. The 15N labeling was conducted in a growth chamber with natural light, with daytime temperatures of 18–28 °C and night time temperatures of 10–15 °C. By the end of the trial, the total amount of Ca(15NO3)2 was 0.2 g·plant−1.

On day 22 after treatment (on a sunny day), five plants from each treatment were randomly selected for 13C labeling. Rootstock seedlings, Ba13CO3 (98% abundance, 0.2 g), fans, and ice were placed inside a sealed labeling chamber constructed from plastic film. The fan and ice were used to ensure air circulation and maintain the temperature of the labeling chamber. The labeling chamber was illuminated by sunlight, with the temperature maintained between 28–35 °C. The labeling process lasted from 8:30 a.m. to 11:30 a.m. Every 30 min, 1 mL of HCl solution (1 mM) was added to a beaker containing Ca(15NO3)2 in the labeling chamber to sustain the CO2 concentration. After the labeling process ended, seedlings were cultured for 72 h before being sampled. The 15N and 13C abundances were measured using a ZHT-03 (Beijing Analytical Instrument Factory, Beijing, China) mass spectrometer. The formulae are as referenced by Wang et al.[26].

Morphological and physiological characteristics and leaf anatomical structure

-

After washing the rootstock seedlings with deionized water, they were separated into leaves, roots, and stems. The plant tissues were dried at 80 °C for 72 h and then weighed to record biomass. Each biological replicate consisted of five plants.

The leaf area of the plant was measured using a leaf area meter (Yaxin-1241, YAXINLIYI TECHNOLOGY LTD, Beijing, China), with the measurements taken from the third to fifth leaves from the top.

The fourth leaf from the top of the plant was collected from different treatments for leaf structure analysis. Following fixation, the tissue underwent a dehydration process using a graded series of ethanol solutions and xylene. The dehydrated tissue was then embedded in paraffin and sectioned. The sections were subjected to staining (with safranin and fast green)[27] and the leaf anatomy was visualized using a microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

Photosynthetic characteristics and chlorophyll fluorescence parameters

-

The measurements of photosynthetic characteristics and chlorophyll fluorescence were conducted on the 25th d after treatment, with the fourth leaf from the top of the plant as the measurement site. The intercellular CO2 concentration (Ci), transpiration rate (Tr), stomatal conductance (gs), and net photosynthetic rate (Pn) were measured using a CIRAS-3 photosynthetic apparatus (PP-SYSTEMS, Amesbury, USA). The linear electron transfer rate (ETR), photochemical quenching coefficient (qP), PSII actual photochemical efficiency (ΦPSII), and maximum photochemical quantum yield of PSII (Fv/Fm) were measured using an FMS-2 portable pulse-modulated fluorometer (Hansatech, UK).

Soluble sugar content and sugar-metabolizing enzyme activities

-

Glucose (Glu), fructose (Fru), sorbitol (Sor), and sucrose (Suc) were extracted from the leaves and roots using ethanol[28]. The dried samples were diluted with distilled water and then analyzed on Waters 1525 HPLC (WATERS CORPORATION, Milford, USA).

The activity of sorbitol dehydrogenase (SDH) was measured according to the method of Zhang et al.[23]. The activity of sucrose-phosphate synthase (SPS) was assessed following the procedure outlined by Vu et al.[29]. The activity of sucrose synthase (SuSy) was determined using the method described by Dancer et al.[30].

Energy states

-

The concentrations of AMP, ADP, and ATP were determined using HPLC (WATERS CORPORATION, Milford, USA), as described by Chen et al.[31]. The energy charge (EC) was calculated as EC = (ATP + 0.5 × ADP)/(ATP + ADP + AMP).

Concentrations of NO3−, NH4+, free amino acid, and soluble protein

-

The content of NO3− was measured using the salicylic acid method as described by Cataldo et al.[32], while the NH4+ concentration was determined using the phenol-hypochlorite method[33]. The free amino acid (FAA) concentrations were assessed using the ninhydrin hydrate method, according to Zhang et al.[34]. The soluble protein (SP) concentration was quantified by the Thomas brilliant blue method[31].

Activities of N-metabolizing enzymes

-

Nitrate reductase (NR) activity was determined using the method described by Ding et al.[35]. The reaction mixture consisted of 0.4 mL of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, 1.2 mL of 0.1 M KNO3, and 0.4 mL of enzyme extract. The reaction was stopped by adding sulfanilamide, and the absorbance at 540 nm was recorded to calculate NR activity.

Glutamine synthetase (GS) activity was measured following the procedure of Oaks et al.[36]. The reaction mixture included 200 μM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid, 4 mM MgSO4, 200 mM Tricine (pH 7.8), 8 mM ATP (pH 7.9), 6 mM hydroxylamine, 80 mM glutamate, and 1.2 mL of enzyme extract. The reaction was stopped by adding 1 mL of 0.37 M FeCl3, and the absorbance at 540 nm was recorded to calculate GS activity.

Glutamate synthase (GOGAT) activity was assessed using the method described by Singh & Srivastava[37]. The reaction mixture consisted of 1 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid, 0.6 mL of 1 mM nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, 0.4 mL of 15 mM 2-oxoglutarate, 0.1 mL of 100 mM KCl, 0.4 mL of 20 mM L-glutamine, and 0.5 mL of enzyme extract. GOGAT activity was calculated by measuring the absorbance at 340 nm.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR

-

Fresh plant samples were ground into a powder in liquid N, and total RNA was extracted using the Total RNA Extraction Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's guidelines. The extracted RNA was then reverse transcribed into cDNA with the PrimeScript First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara, Japan). The cDNA served as a template for quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), which was conducted in a 20 μL reaction volume containing SYBR Green (TaKaRa, RR420A). Relative gene expression levels were determined using the 2−ΔΔCᴛ method, with MdActin as the internal control gene for data normalization. Primer sequences for the target genes are provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Statistical analysis

-

Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 22.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Duncan's post-hoc test was applied to evaluate the statistical significance of the results, with p ≤ 0.05 considered significant. The plots were generated using Origin 2021 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA).

-

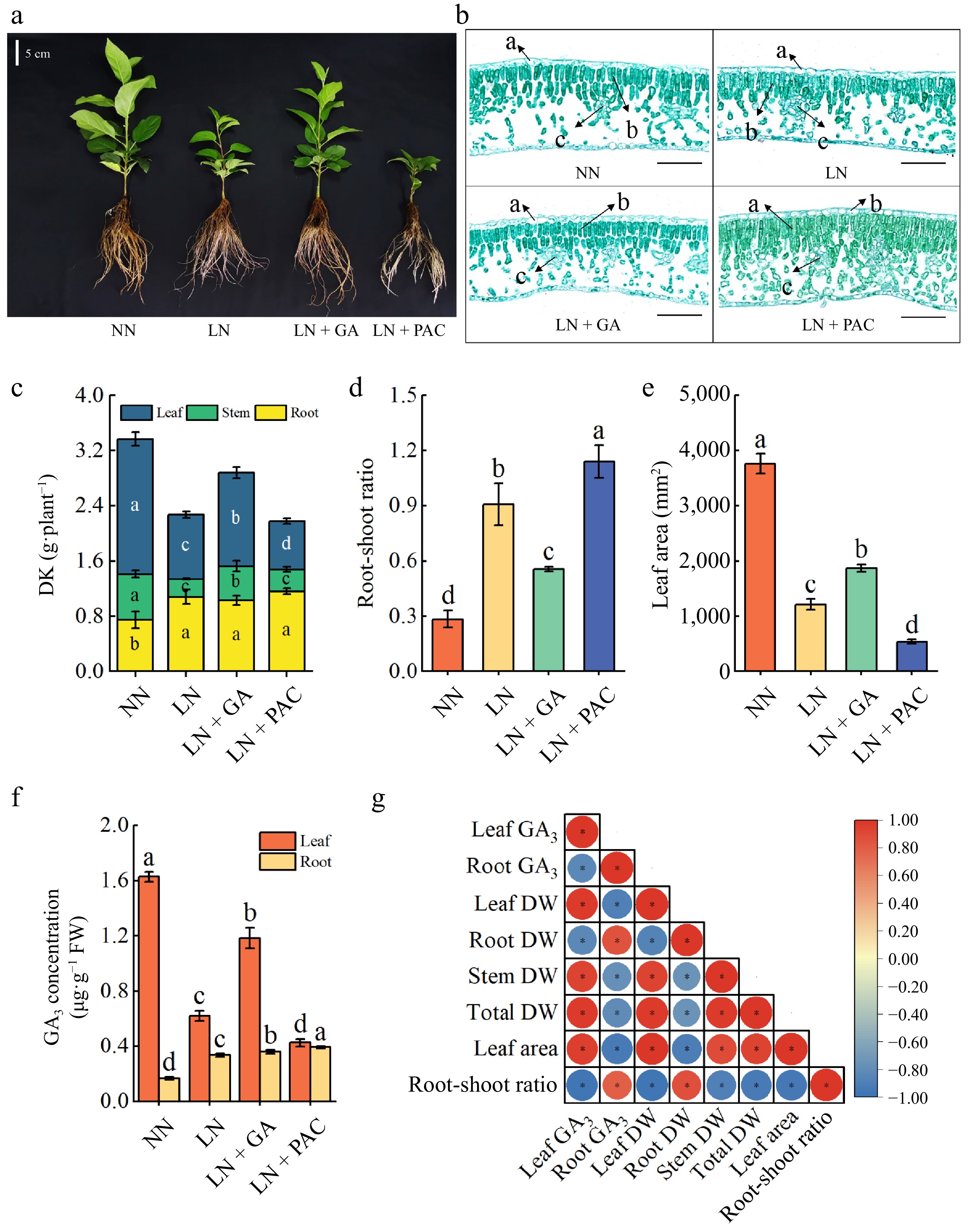

Both N supply levels and exogenous GA3 application significantly affected the growth of rootstock seedlings after 25 d of treatment (Fig. 1a–e). All growth traits, except for root dry weight, were significantly inhibited in plants treated with LN compared to those treated with NN. However, GA3 treatment significantly increased stem dry weight (91.04%), leaf dry weight (45.00%), total dry weight (26.69%), and leaf area (54.12%), and decreased the root-shoot ratio in LN plants, but had no significant effect on root dry weight. In addition, PAC application had the opposite effect compared to the application of GA3.

Figure 1.

Effects of exogenous GA3 and PAC on the (a) growth, (b) leaf anatomical structure, (c) dry weight, (d) root-shoot ratio, (e) leaf area, and (f) endogenous GA3 concentration of apple rootstocks under low-N stress, and (g) correlation analysis. In (b), 'a' represents epidermis, 'b' represents palisade tissue, 'c' represents vascular bundle, and the scale is 100 μm. DW: dry weight; NN: plants under normal N supply (5 mM NO3−); LN: plants under low N supply (0.5 mM NO3−); GA: GA3; PAC: paclobutrazol. Vertical lines indicate the standard deviation (± SD) for a sample size of n = 5. The presence of different letters indicates a statistically significant difference at the 5% level (p < 0.05).

The GA3 concentration in the leaves and roots of the plants was quantified, revealing a notable reduction in the GA3 concentration in the leaves of the LN treatment in comparison to the NN treatment. In contrast, the LN + GA treatment resulted in a significant increase in GA3 concentration in the leaves of LN plants (47.63%), with no effect on the GA3 concentration in the roots (Fig. 1f). The results of the statistical analysis showed that there was a significant positive correlation between the GA3 concentration in the leaves and leaf dry weight, stem dry weight, and total dry weight. Conversely, a significant negative correlation was observed between the GA3 concentration in the leaves and the root-shoot ratio (Fig. 1g).

The differences in leaf tissue structure of apple rootstock seedlings between different treatments were further revealed by Safranin-O and Fast Green staining (Fig. 1b). Plants under the LN treatment had tighter palisade tissues than those under the NN treatment. In contrast, the LN + GA treatment resulted in looser palisade tissues and denser chloroplasts, whereas the LN + PAC treatment increased the tightness of fenestrated tissues in LN plants.

Effect of exogenous GA3 application on the photosynthetic characteristics and energy status

-

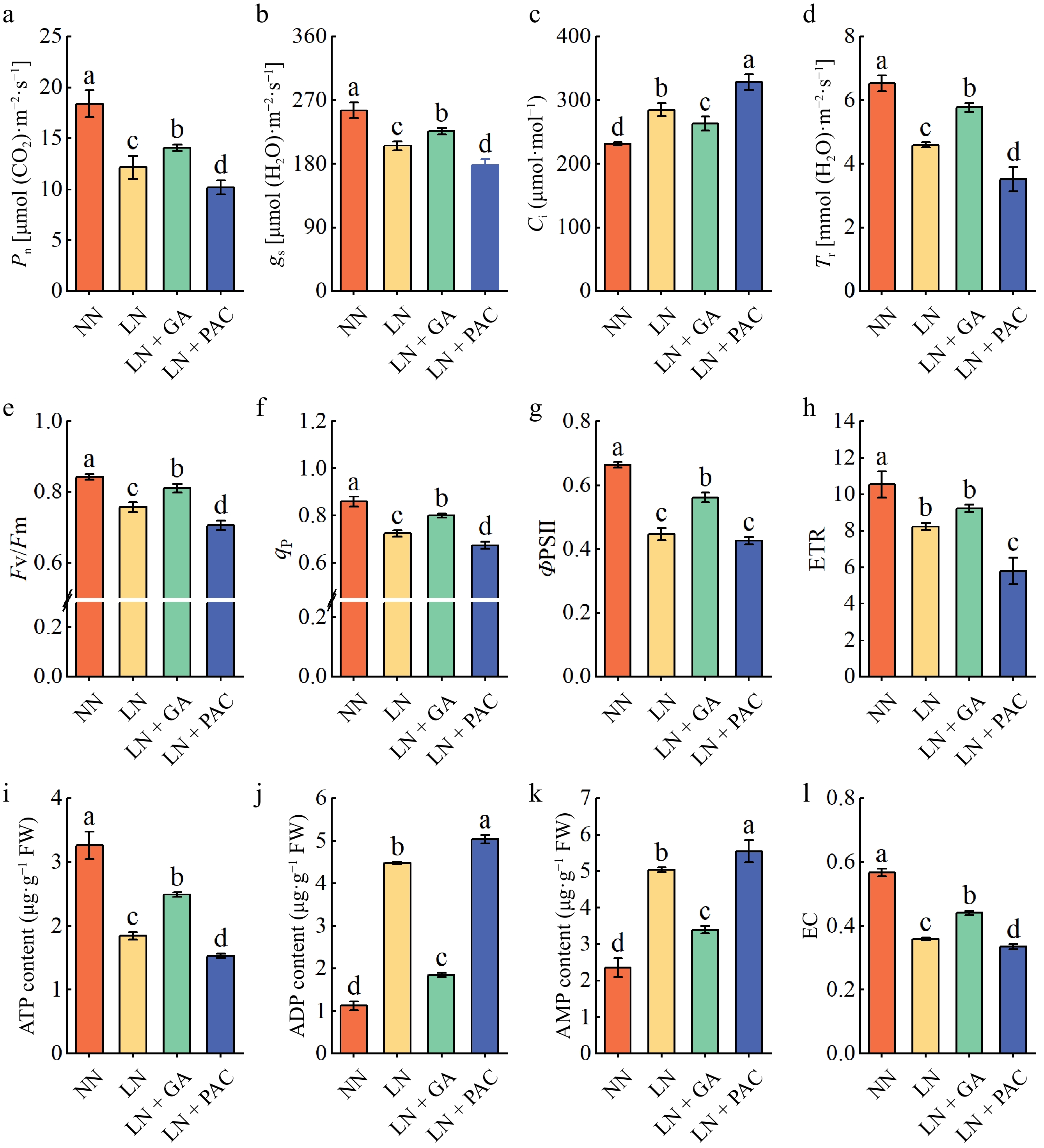

In comparison to the NN treatment, the LN treatment significantly reduced the Pn, gs, and Tr, whereas Ci was significantly elevated under the LN treatment. The application of exogenous GA3 resulted in a significant increase in Pn and a significant reduction in Ci in LN plants, whereas exogenous PAC treatment exacerbated the decline in Pn (Fig. 2a−d).

Figure 2.

Effects of exogenous GA3 and PAC on photosynthetic parameters (a) Pn; (b) gs; (c) Ci; (d) Tr, chlorophyll fluorescence (e) Fv/Fm; (f) qp; (g) ΦPSII; (h) ETR, and energy states (i) ATP content in leaves; (j) ADP content in leaves; (k) AMP content in leaves; (l) EC in leaves of apple rootstocks under low-N stress. ΦPSII: PSII actual photochemical efficiency; Fv/Fm: maximum photochemical quantum yield of PSII; qp: photochemical quenching coefficient; ETR: linear electron transfer rate; EC: energy charge; NN: plants under normal N supply (5 mM NO3−); LN: plants under low N supply (0.5 mM NO3−); GA: GA3; PAC: paclobutrazol. Vertical lines indicate the standard deviation (± SD) for a sample size of n = 5. The presence of different letters indicates a statistically significant difference at the 5% level (p < 0.05).

Chlorophyll fluorescence parameters are important indicators for further understanding the photosynthetic physiological status of plants. Following a 25-d period of treatment, significant reductions in Fv/Fm, ΦPSII, qP, and ETR were observed in the LN plants in comparison to the NN plants. In addition, the chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of LN plants were significantly restored under the LN + GA treatment, whereas those of rootstock seedlings under the LN + PAC treatment were further reduced (Fig. 2e−h).

The ATP, ADP, AMP, and EC contents provide a direct indication of a plant's energy utilization status. In comparison to the NN treatment, the LN treatment resulted in a notable reduction in ATP content and EC, while significantly increasing the ADP and AMP contents (Fig. 2i−l). Exogenous GA3 treatment significantly increased ATP content and energy charge (EC) in LN plants, whereas PAC had the opposite effect.

Effect of exogenous GA3 application on soluble sugar concentration and activity of sugar-metabolizing enzymes

-

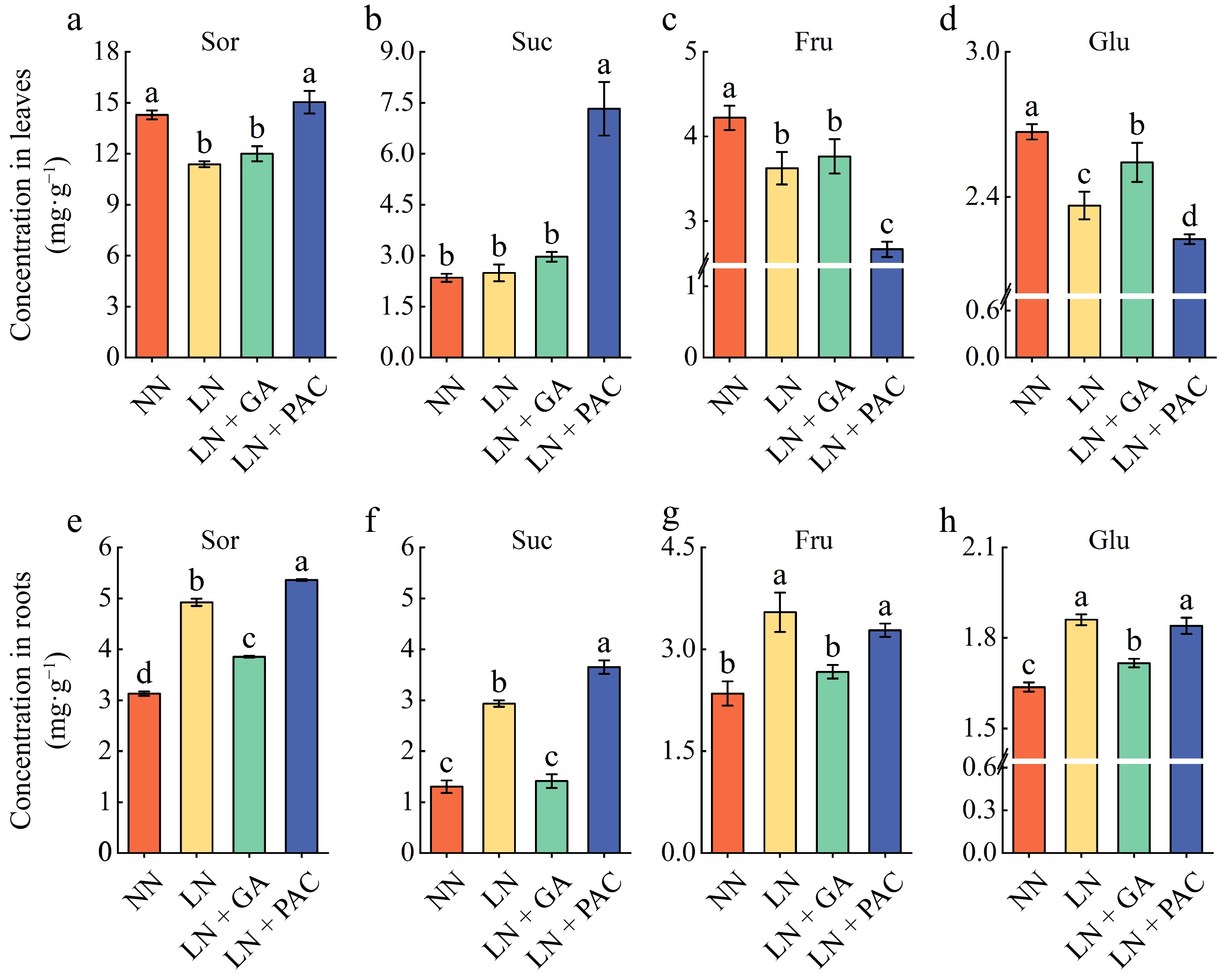

Sucrose (Suc), sorbitol (Sor), fructose (Fru), and glucose (Glu) were the main soluble sugars in the rootstock seedlings. In comparison to the NN treatment, the levels of soluble sugars in the leaves were markedly diminished under the LN treatment, except for Suc (Fig. 3). Exogenous GA3 application led to a significant increase in Glu concentration in the leaves of LN plants, while no notable effect was observed on the other three soluble sugars. In the roots, the levels of all four soluble sugars in the LN + GA treatment were markedly lower compared to the LN treatment. Additionally, PAC treatment significantly increased Suc and Sor content but significantly decreased Fru and Glu content in the leaves of LN plants.

Figure 3.

Effects of exogenous GA3 and PAC on soluble sugar concentrations of apple rootstocks under low-N stress. The Sor concentration in (a) leaves and (e) roots. The Suc concentration in (b) leaves and (f) roots. The Fru concentration in (c) leaves and (g) roots. The Glu concentration in (c) leaves and (g) roots. Sor: sorbitol; Suc: sucrose; Fru: fructose; Glu: glucose; NN: plants under normal N supply (5 mM NO3−); LN: plants under low N supply (0.5 mM NO3−); GA: GA3; PAC: paclobutrazol. Vertical lines indicate the standard deviation (± SD) for a sample size of n = 5. The presence of different letters indicates a statistically significant difference at the 5% level (p < 0.05).

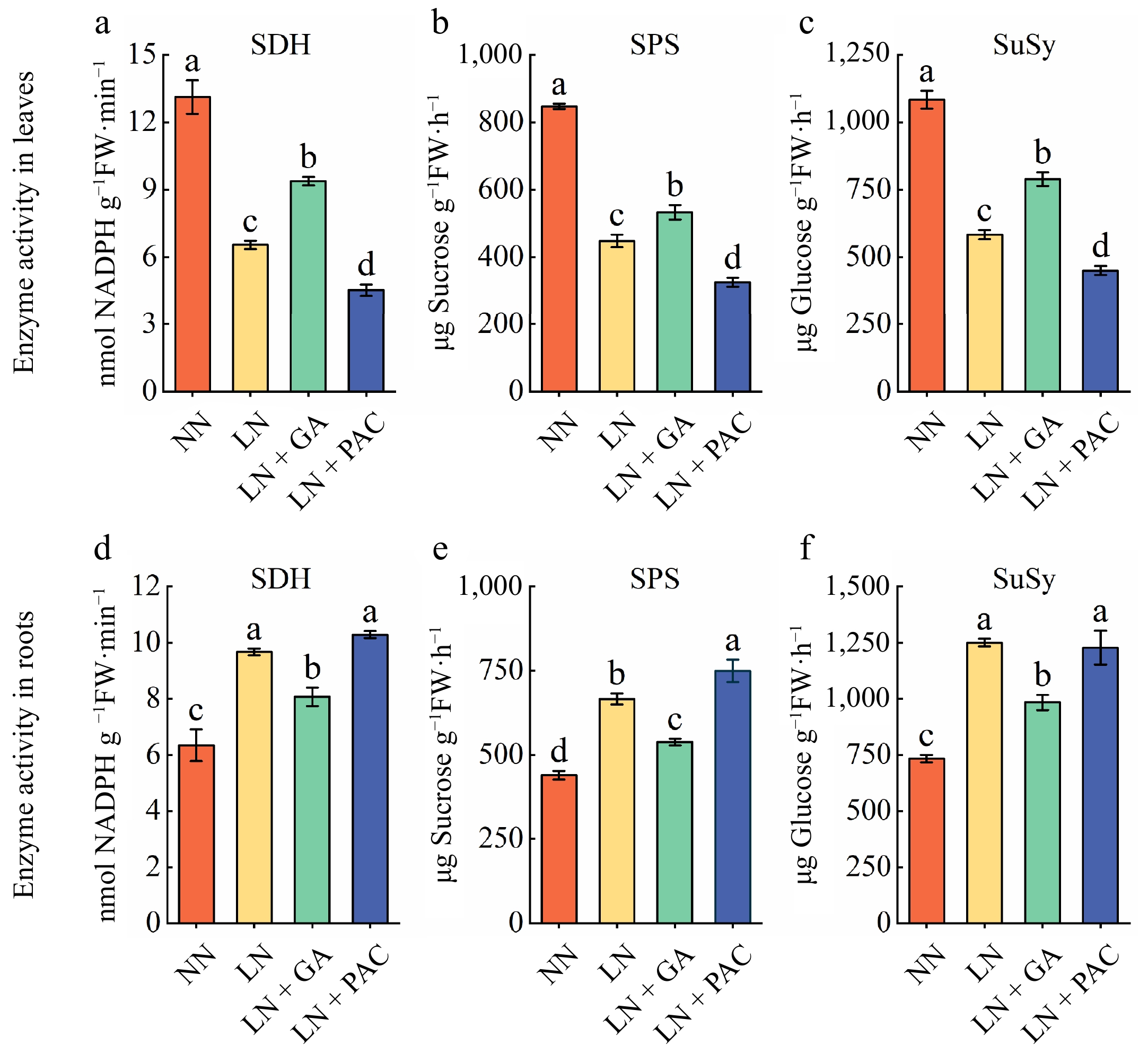

SPS and SuSy catalyze the synthesis and degradation of Suc, while SDH catalyzes the degradation of Sor. In comparison to the NN treatment, the activities of SDH, SPS, and SuSy were significantly decreased in the leaves but significantly increased in the roots of plants subjected to LN treatment (Fig. 4). The LN + GA treatment significantly elevated the activities of SDH, SPS, and SuSy in the leaves of LN plants but played the opposite role in the roots. In addition, PAC treatment further reduced the activities of the three sugar-metabolizing enzymes in the leaves of LN plants but had no significant influence on SDH and SuSy activities in the roots.

Figure 4.

Effects of exogenous GA3 and PAC on sugar-metabolizing enzyme activities of apple rootstocks under low-N stress. The SDH activity in (a) leaves and (d) roots. The SPS activity in (b) leaves and (e) roots. The SuSy activity in (c) leaves and (f) roots. SDH: sorbitol dehydrogenase; SPS: sucrose-phosphate synthase; SuSy: sucrose synthase; NN: plants under normal N supply (5 mM NO3−); LN: plants under low N supply (0.5 mM NO3−); GA: GA3; PAC: paclobutrazol. Vertical lines indicate the standard deviation (± SD) for a sample size of n = 5. The presence of different letters indicates a statistically significant difference at the 5% level (p < 0.05).

Effect of exogenous GA3 application on the expression of sugar transporters and C allocation

-

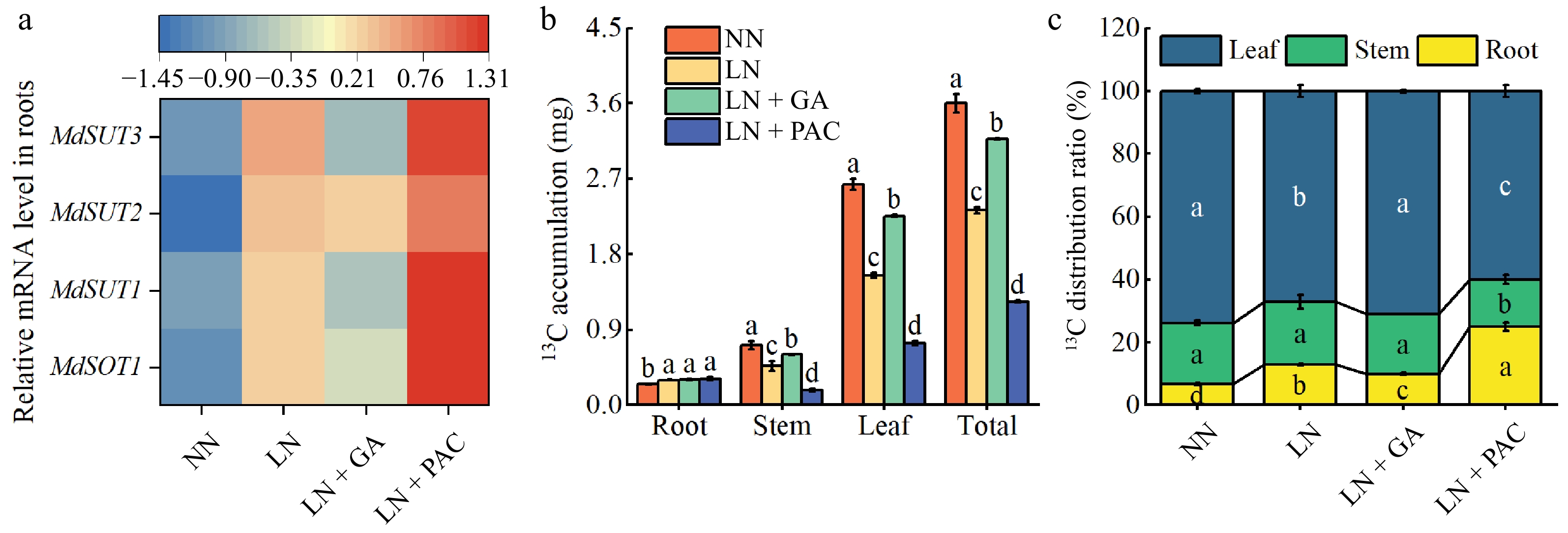

MdSOT1 and MdSUTs are involved in Sor and Suc unloading of from apple rootstock seedlings. In comparison to the NN treatment, the LN treatment resulted in an increase in expression of MdSOT1, MdSUT1, MdSUT2, and MdSUT3 (Fig. 5a). However, in contrast to the LN treatment, the application of GA3 decreased the expression of MdSOT1, MdSUT1, MdSUT2, and MdSUT3 in the roots, whereas the LN + PAC treatment increased their expression.

Figure 5.

Effects of exogenous GA3 and PAC on transcription levels of genes encoding (a) sugar transporters, (b) 13C accumulation, and (c) 13C distribution ratio of apple rootstocks under LN stress; NN: plants under normal N supply (5 mM NO3−); LN: plants under low N supply (0.5 mM NO3−); GA: GA3; PAC: paclobutrazol. Vertical lines indicate the standard deviation (± SD) for a sample size of n = 5. The presence of different letters indicates a statistically significant difference at the 5% level (p < 0.05).

13C stable isotope labeling revealed the accumulation of C in different organs of plants. In comparison to the NN treatment, the LN treatment was observed to significantly enhance the accumulation and distribution ratio of 13C in the roots, whereas the total accumulation and distribution ratio in the leaves were significantly reduced (Fig. 5b, c). The LN + GA treatment significantly increased the distribution ratio of 13C in the leaves, and significantly enhanced 13C accumulation in the stems, leaves, and whole plants of LN-treated plants. Furthermore, the application of PAC reduced the 13C distribution ratio and accumulation in the leaves and stems of LN plants.

Effect of exogenous GA3 on the concentration of N assimilation products and enzyme activities

-

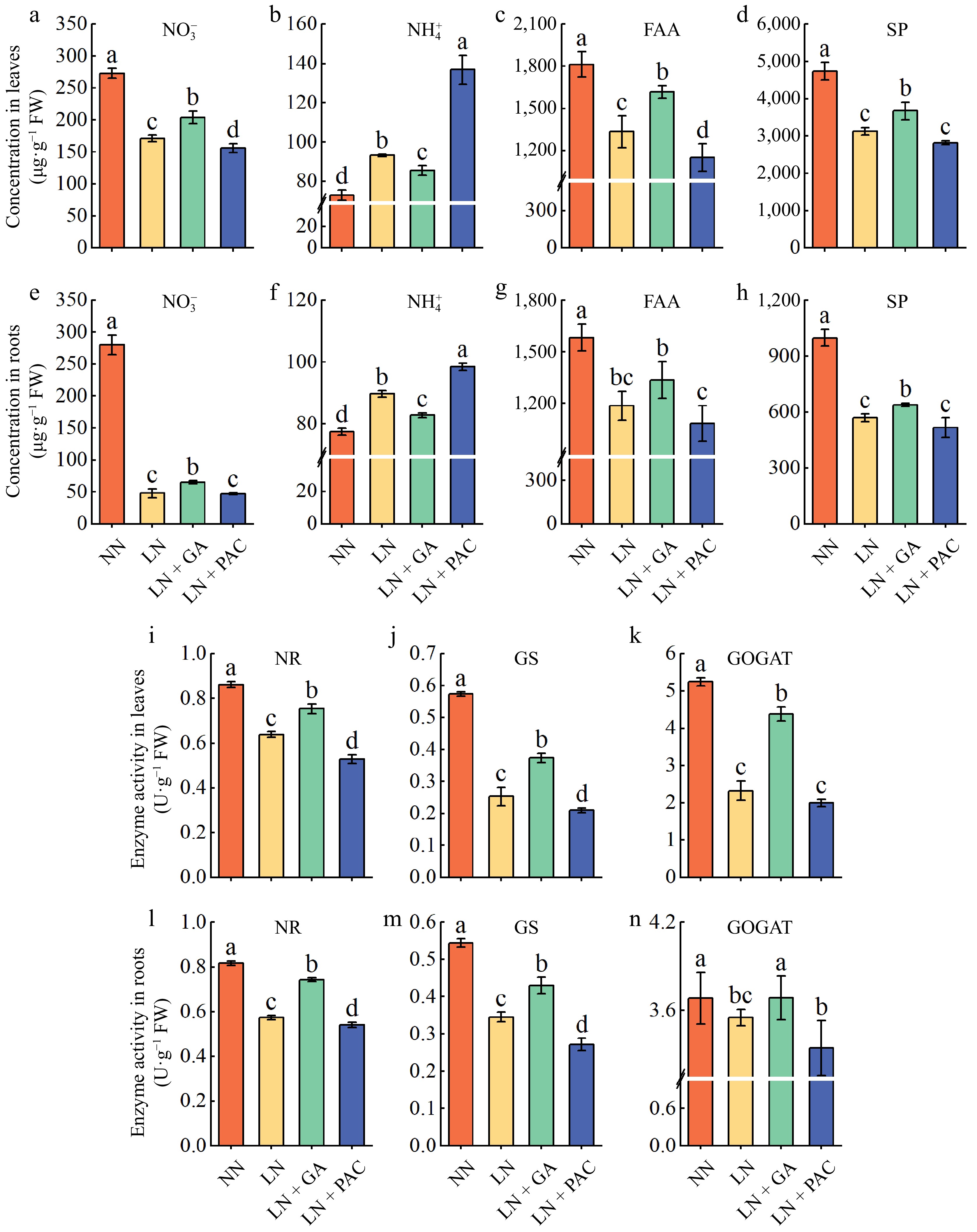

As shown in Fig. 6a−h, the LN treatment significantly decreased the concentrations of NO3−, FAA, and SP in plant leaves and roots compared to the NN treatment, but significantly increased the concentration of NH4+. In addition, spraying exogenous GA3 significantly increased NO3−, free amino acid (FAA), and soluble protein (SP) contents, and significantly decreased NH4+ contents in leaves and roots of plants under LN treatment, whereas spraying PAC produced the opposite effect.

Figure 6.

Effects of exogenous GA3 and PAC on the concentration of N metabolism intermediates and N metabolism enzyme activities of apple rootstocks under low-N stress. The NO3− concentration in (a) leaves and (e) roots. The NH4+ concentration in (b) leaves and (f) roots. The FAA concentration in (c) leaves and (g) roots. The SP concentration in (c) leaves and (g) roots. The NR activity in (i) leaves and (l) roots. The GS activity in (j) leaves and (m) roots. The GOGAT activity in (k) leaves and (n) roots. FAA: free amino acid; SP: soluble protein; NR: nitrate reductase; GS: glutamine synthetase; GOGAT: glutamate synthase; NN: plants under normal N supply (5 mM NO3−); LN: plants under low N supply (0.5 mM NO3−); GA: GA3; PAC: paclobutrazol. Vertical lines indicate the standard deviation (± SD) for a sample size of n = 5. The presence of different letters indicates a statistically significant difference at the 5% level (p < 0.05).

We determined the changes in the activities of key enzymes in the N-assimilation process under different treatments to further investigate the effect of exogenous GA on N metabolism in plants (Fig. 6i−n). After 25 d of treatment, the activities of the three enzymes measured subjected to the LN treatment were significantly lower than those observed in plants treated with NN. Exogenous GA3 treatment significantly mitigated the inhibitory effects on N-metabolizing enzyme activity in LN-treated plants, whereas PAC treatment worsened this effect.

Effect of exogenous GA3 on the expression of NO3− transporters, N allocation, and 15NUE

-

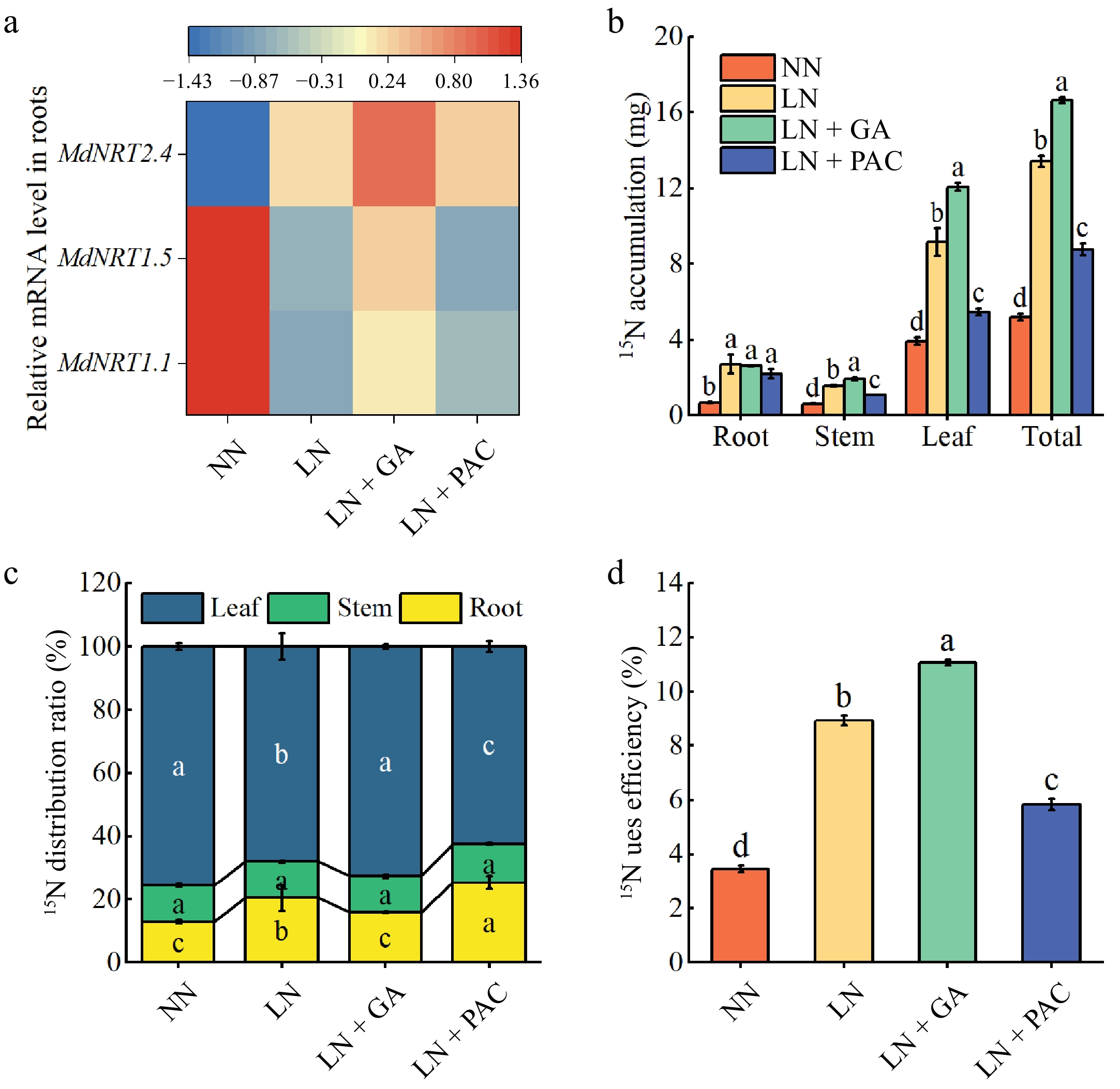

MdNRT1.1, MdNRT1.5, and MdNRT2.4 are involved in NO3− uptake and transport. In comparison to the NN treatment, the expression of MdNRT1.1 and MdNRT1.5 were significantly decreased in plants under the LN treatment. Exogenous GA3 treatment significantly alleviated this inhibition and increased the expression of MdNRT2.4 (Fig. 7a).

Figure 7.

Effects of exogenous GA3 and PAC on transcription levels of genes encoding (a) NO3− transporters, (b) 15N accumulation, (c) 15N distribution ratio, and (d) 15N use efficiency of apple rootstocks under low-N stress; NN: plants under normal N supply (5 mM NO3−); LN: plants under low N supply (0.5 mM NO3−); GA: GA3; PAC: paclobutrazol. Vertical lines indicate the standard deviation (± SD) for a sample size of n = 5. The presence of different letters indicates a statistically significant difference at the 5% level (p < 0. 05).

The 15N stable isotope labeling results revealed the impact of different treatments on N uptake and allocation in plants. As shown in Fig. 7b−d, 15N use efficiency (15NUE) and 15N accumulation were markedly elevated under the LN treatment in comparison to the NN treatment. Exogenous GA3 treatment further enhanced these parameters in the LN-treated plants. Additionally, exogenous GA3 application resulted in a notable enhancement in 15N distribution ratio in the leaves of LN plants, whereas PAC application had the opposite effect.

-

N in the soil is a key limiting factor for plant growth and development, and the application of N fertilizer greatly benefits crop yield. However, excessive N fertilization poses a significant challenge to apple cultivation, including environmental pollution, reduced fruit quality, and ultimately lower economic benefits. Improving the growth and NUE of apple rootstocks under low N supply, and thus reducing N application, is an important means of solving the problem of excessive N application. GA plays an important role in plant leaf expansion and stem elongation by stimulating cell division and expansion[38]. Genes related to GA synthesis are downregulated under low-N stress, leading to a reduction in GA levels and consequently slowing the growth of the aerial parts[39]. In the present study, exogenous GA3 promoted endogenous GA3 content and the growth of aerial parts of apple rootstock seedlings under low-N stress, whereas PAC reduced endogenous GA3 content and exacerbated growth inhibition (Fig. 1a, c & f). This indicates that the increased GA3 concentration in the leaves contributes to enhancing the low-N stress tolerance of apple rootstock seedlings. We analyzed the effects of exogenous GA3 on C and N metabolism under N deficiency to further explore the physiological mechanisms involved. The results showed that C and N metabolism, allocation, and energy status were significantly regulated by exogenous GA3 and played an important role in alleviating low-N stress.

Effect of exogenous GA3 on C metabolism and allocation under low-N stress

-

N deficiency reduces plant photosynthesis via stomatal and non-stomatal factors[22]. In this study, we found that the reduction in Pn and gs in apple rootstock seedlings under the LN treatment was accompanied by an increase in Ci, suggesting that non-stomatal limitation contributes to the reduction of photosynthesis (Fig. 2a−c). Prior research has demonstrated that N deficiency inhibits the synthesis of light-harvesting and photosynthetic enzymes, leading to reduced electron transport rate and carboxylation efficiency, while increasing the dissipation of light energy as heat and fluorescence[40,20]. Similarly, we found that N deficiency resulted in a reduction in the concentration of SP (Fig. 6d) in leaves and decreased Fv/Fm, ETR, qP, and ΦPSII (Fig. 2e−h). Exogenous GA3 alleviated the inhibition of photosynthesis by low-N stress, whereas PAC treatment led to a further decline in photosynthesis (Fig. 2a). The reason for this result may be that exogenous GA3 promoted NO3− uptake and assimilation, thereby alleviating the deficiency of photosynthetic proteins under low-N stress. Furthermore, the optimization of leaf anatomy by exogenous GA3 under low N stress may also contribute positively to photosynthesis. In our study, spraying exogenous GA3 resulted in N-deficient leaves with more loosely arranged palisade tissue and larger intercellular spaces compared to the LN treatments (Fig. 1b), which facilitated CO2 conductance and light trapping[41,42]. Additionally, other studies have shown that GA can enhance photosynthesis by increasing chlorophyll and carotenoid biosynthesis or by stimulating RuBisCO activity[43]. However, many studies have indicated that GA inhibits the expression of photosynthetic genes[44,45]. Thus, further research is needed to explore the underlying mechanisms by which exogenous GA3 influences photosynthesis in N-deficient plants.

Exogenous GA3 significantly affected sugar metabolism, transport, and C allocation under low N stress. Cell division and expansion require photosynthetic products for both nutrients and energy. In apples, Sor and Suc are the predominant end products of photosynthesis, serving as C sources and energy for of sink organs[46]. In addition, they are the main forms of carbohydrates transported over long distances in apple trees. Once released from the phloem, they are rapidly absorbed into the cytoplasm of sink organs via sorbitol and sucrose transporters[23]. Consistent with the findings of Zhao et al.[4], we found that low N stress increased the carbohydrate translocation to the root system to promote root growth. Exogenous GA3 reduced the expression of sucrose transporters (MdSUT1 and MdSUT3) and sorbitol transporter (MdSOT1) and decreased the accumulation of Suc and Sor in the roots under LN stress (Figs 5a, 3e & f), suggesting that exogenous GA3 reduced the translocation of photosynthetic products to the roots. Despite an increase in photosynthesis and a decrease in the output of photosynthetic products, exogenous GA3 did not increase the content of Sor and Suc in the leaves of plants under LN stress (Fig. 3a & b). This may be due to the increased activities of SDH and SuSy (Fig. 4a & b), which catalyze the degradation of Sor and Suc, respectively[47]. SuSy activity is regarded as an indicator of sink strength, and exogenous GA3 reduced SuSy activity in roots under low N stress, suggesting that root sink strength was weakened and more photosynthetic products were utilized in the leaves[48]. This was supported by the results of 13C isotope labeling, where we found that exogenous GA3 significantly increased 13C accumulation in the whole plant and the distribution ratio in the leaves under LN stress (Fig. 5c). Theoretically, increased SDH and SuSy activity would lead to an increase in Fru concentration, the product of Sor and Suc degradation. However, our results showed that the concentration of Fru in the leaves of plants treated with LN + GA did not significantly elevate compared to those treated with LN (Fig. 3c). This may be due to an increased rate of Fru degradation, as we observed that exogenous GA3 enhanced ATP content and EC in leaves under low N stress (Fig. 2i−l). An increased rate of Fru degradation enhances the C flux through the TCA cycle and glycolysis, thus boosting the production of intermediates and ATP, which provide energy and substrates for the Calvin cycle and other metabolic processes[4,49]. Therefore, exogenous GA3 may promote photosynthesis and leaf growth by improving the utilization of photosynthetic products in leaves. It has been reported that GA affects the utilization of photosynthetic products and the consumption of hexoses in plants such as maize[14], ryegrass[50], and tobacco[51], but the exact mechanisms remain unclear. Therefore, further investigation into the effects of GA on plant C metabolism is crucial.

Effect of exogenous GA3 on N metabolism and allocation under low-N stress

-

As the main inorganic N source absorbed by terrestrial plants, the uptake, transport, assimilation, and reuse of NO3− are critically important for plant processes. NO3− is not only a nutrient that composes biomolecules such as proteins, nucleic acids, and phytohormones but also serves as a local and systemic signal that triggers downstream responses to fluctuations in external NO3− levels. Nitrate transporters (NRTs) are involved in the composition of high-affinity and low-affinity transport systems and mediate NO3− uptake in plants. Previous reports stated that MdNRT1.1 and MdNRT2.4 were the main contributors to NO3− uptake in apple trees exposed to N deficiency[52]. We observed that LN treatment decreased the expression level of MdNRT1.1, while increasing the transcriptional level of MdNRT2.4 (Fig. 7a), which is similar to the results of Chai et al.[53]. As a high-affinity NO3− transporter, the increased transcript level of MdNRT2.4 facilitates NO3− uptake by apple rootstocks under low N stress. Exogenous GA3 increased both MdNRT1.1 and MdNRT2.4 expression and increased NO3− concentration in the roots (Figs 7a & 6a). Previous studies have shown that MdNRT2.4 in apple not only enhances NO3− uptake capacity but also increases rhizosphere N concentration through interactions with rhizobia[53]. Wang et al.[54] also proposed that the NO3− transporter MdNPF6.5 is a candidate gene for improving NO3− uptake under low N conditions in apple. Therefore, in this experiment, exogenous GA3 played an important role in regulating NO3− uptake capacity, contributing to the alleviation of low-N stress in apple seedlings. In addition to the transcriptional level, GA may also regulate NRTs through post-translational modifications[14,10], although the exact mechanism is not clear.

After uptake by roots, NO3− is reduced to NH4+ under the catalysis of NR and nitrite reductase (NiR), and the site of assimilation depends on the species and external conditions. NO3− transport from roots to shoots is primarily driven by transpiration at the leaf surface, but it is also influenced by the interactions between the xylem and phloem[55]. MdNRT1.5 participates in mediating the loading of NO3− into the xylem of apple roots, thereby regulating the long-distance transport of NO3−[56]. In this study, we found that LN stress reduced the transcript levels of MdNRT1.5 (Fig. 7a), which may lead to a decrease in the translocation of NO3− to the shoot. It was reported that various stresses could increase NO3− reallocation to the root of plants to regulate stress tolerance, but the exact pathways remain ambiguous[57]. Notably, exogenous GA3 increased the expression of MdNRT1.5 under LN stress, whereas PAC decreased the expression of MdNRT1.5 (Fig. 7a), suggesting that exogenous GA3 facilitates the upward transport of NO3−. NO3− is assimilated in leaves may be more energy efficient than in roots because ATP and reductants produced by photosynthesis can be directly utilized in leaves[57]. Additionally, spraying GA3 alleviated the inhibition of NR, GS, and GOGAT activity by LN stress and increased the concentrations of FAA and SP, suggesting that NO3− assimilation was promoted. NR is a rate-limiting enzyme in the plant N assimilation process. In Arabidopsis, ectopic expression of MdNIA2, a gene responsible for encoding NR in apple, can enhance NUE and promote plant growth[58]. The GS/GOGAT cycle is responsible for the assimilation of NH4+ into glutamate. In apple, a decrease in GS activity reduces N accumulation and leads to chlorophyll deficiency[59]. The promotion of N-assimilating enzymes by exogenous GA3 may be attributed to increased NO3− levels (Fig. 6a), photosynthesis (Fig. 2a), and EC (Fig. 2l). The gene encoding NR can be induced by NO3− in a short period, and photosynthesis is required for NR activation[60,61]. Simultaneously, the GS/GOGAT cycle depends on the supply of the C skeleton and ATP[62]. In rice, the transcription factor GRF4 (an essential element of the GA signaling pathway) activates the transcription of several N metabolism genes, including GS1.2, GS2 and NADH-GOGAT2[12]. Sun et al.[63] claimed that GA promotes plant N metabolism by inhibiting flavonoid biosynthesis. Hence, the exact pathways through which GA promotes N metabolism require further investigation. Moreover, previous studies have primarily focused on the effects of GA on tree shape[64], flowering[65], and fruit quality[66] in apple, with limited research on how GA influences C and N metabolism in apples. Therefore, investigating the molecular mechanisms by which GA regulates C and N metabolism in apples is a promising area of research.

We labeled rootstock seedlings with 15N to further understand the effects of exogenous GA3 on N uptake, assimilation, and allocation under low N stress. Exogenous GA3 increased total 15N accumulation and improved 15N distribution in the leaves under LN stress (Fig. 7b & c). Previous studies have shown that NO3− assimilation occurs predominantly in roots when external NO3− concentrations are low[67]. In addition, N deficiency activates foraging responses in roots and increases their sink strength, which can increase amino acid transport from leaves to roots[68]. Thus, exogenous GA3 may have increased the 15N distribution ratio in leaves under low N stress by enhancing leaf N assimilation and reducing root sink strength. Increased leaf N allocation often implies higher NUE[69], as evidenced by the increase in15NUE caused by exogenous GA3 in rootstock seedlings under LN stress (Fig. 7d). In summary, exogenous GA3 promoted NO3− uptake and assimilation and increased leaf N allocation, and thus improved the plant's resistance to LN stress. Furthermore, our study demonstrated that exogenous GA3 does not act alone in C or N metabolism but promotes plant growth under N-deficient conditions by coordinating their interactions. However, the specific mechanism by which exogenous GA3 coordinates C and N metabolism requires further investigation.

-

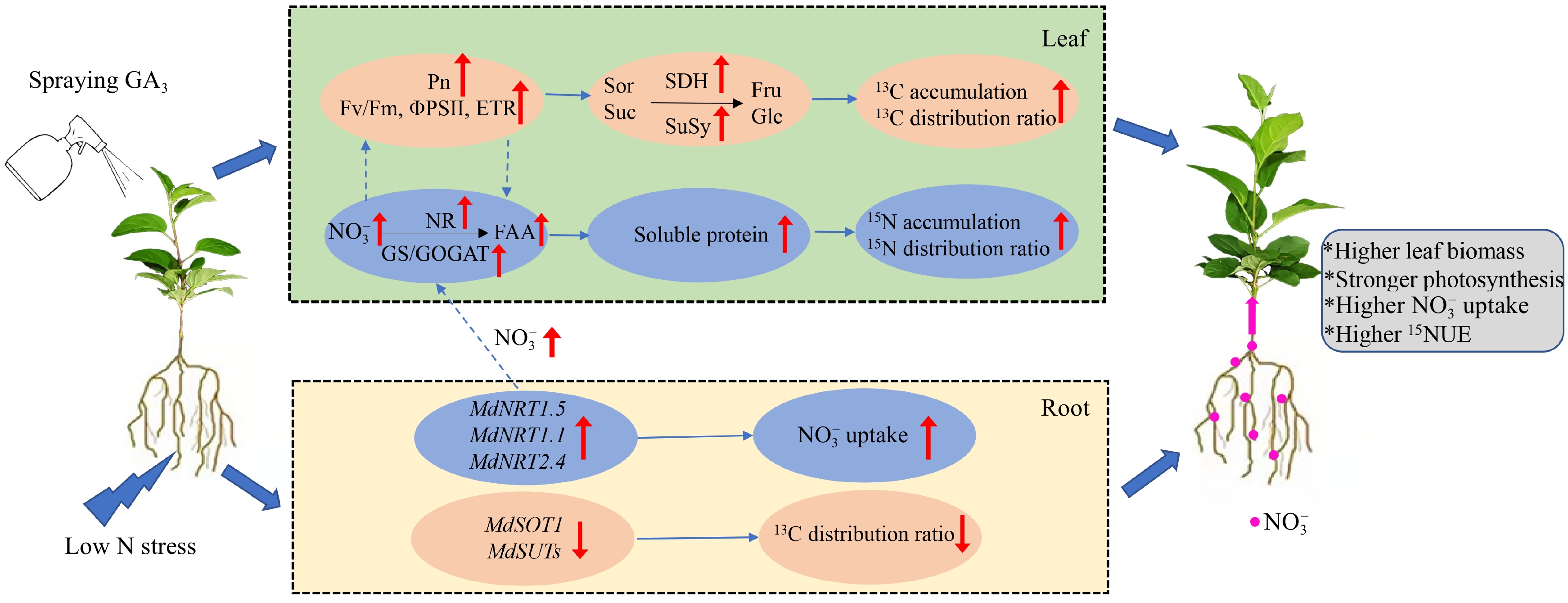

Our results showed that low N stress decreased the soluble protein content in plants, leading to suppressed photosynthesis and increased allocation of C and N nutrients in the roots, which in turn inhibited leaf growth and function. Exogenous GA3 reduced the inhibition of leaf growth under low-N stress by coordinating the allocation of C and N between the leaves and roots and enhancing the C and N assimilation capacity in the leaves (Fig. 8). Under N deficiency conditions, spraying 50 mg·L−1 GA3: (1) improved expression of MdNRT1.1, MdNRT2.4, and MdNRT1.5, thereby facilitating NO3− uptake and upward transport; (2) activated N assimilation-related enzymes (i.e., NR, GS, and GOGAT) activities, thereby increasing FAA and SP contents; (3) enhanced leaf photosynthesis and sugar metabolism enzyme (SPS, SDH, and SuSy) activities that thereby increasing EC and 13C accumulation; (4) reduced root MdSOT1, MdSUT1, MdSUT2, and MdSUT3 expression, thereby decreasing leaf-to-root translocation of sucrose and sorbitol; and (5) optimized C and N allocation, increasing the 13C and 15N distribution ratio in shoots and improving 15NUE. These findings provide new insights into how exogenous GA3 mitigates low N stress in apple plants.

This work was supported by the Key R&D Program of Shandong Province, China (2024CXGC010903), the Special Fund for the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2021MC093), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFD2301000), the earmarked fund for CARS (CARS-27), the Taishan Scholar Assistance Program from Shandong Provincial Government (TSPD20181206), and Xin Lianxin Innovation Center for Efficient Use of Nitrogen Fertilizer (2020-apple).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Liu J, Ge S, Jiang Y; data collection: Lyu M, Liu C, Ni W, Guan Y; analysis and interpretation of results: Xie H, Xing Y, Feng Z, Zhu Z; draft manuscript preparation: Liu J, Ge S. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplementary Table S1 Primer sequences for qRT-PCR.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Liu J, Lyu M, Liu C, Ni W, Guan Y, et al. 2025. Exogenous GA3 alleviates low nitrogen stress by enhancing leaf nitrogen assimilation and limiting the transport of photosynthates to roots in apple plants. Fruit Research 5: e018 doi: 10.48130/frures-0025-0009

Exogenous GA3 alleviates low nitrogen stress by enhancing leaf nitrogen assimilation and limiting the transport of photosynthates to roots in apple plants

- Received: 20 December 2024

- Revised: 13 February 2025

- Accepted: 27 February 2025

- Published online: 06 May 2025

Abstract: Gibberellins (GAs) are crucial for improving plant adaptation to abiotic stresses; however, their physiological functions in apple plants under low-nitrogen (N) stress remain unclear. In this work, a hydroponic approach was used to explore the effects of exogenous GA3 on carbon (C)-N metabolism and allocation in apple seedlings under low-N stress. The results indicated that the application of exogenous GA3 (50 mg·L−1) enhanced the concentration of endogenous GA3 in the leaves, alleviated the inhibition of photosynthesis and leaf growth caused by low-N stress, and significantly increased plant biomass (21%). In terms of N metabolism, exogenous GA3 enhanced the transcription levels of nitrate transporters and increased leaf N-assimilating enzyme activities, leading to an increase in nitrate and soluble protein content. Additionally, exogenous GA3 significantly increased the distribution ratio of 15N in the leaves and the expression of MdNRT1.5 in the roots, indicating that more N was utilized in the leaves. Regarding C metabolism, exogenous GA3 improved the utilization of photosynthetic products by leaves under low N stress. Specifically, GA3 application enhanced the activities of sorbitol dehydrogenase and sucrose synthase in the leaves, while reducing the expression of sugar unloading-related genes in the roots, leading to significant increases in the 13C distribution ratio and energy charge (EC) in the leaves. In conclusion, our study demonstrated that exogenous GA3 promotes the recovery of leaf growth and function under low-N stress by enhancing the allocation and utilization of C and N in the leaves.

-

Key words:

- Gibberellin /

- Low-nitrogen stress /

- Nitrogen metabolism /

- Apple /

- 15N /

- 13C