-

Zinc is one of the most extensively used and toxic heavy metals. The World Health Organization has recommended that the maximum acceptable concentration of zinc is 0.05 mg·L−1 in surface and ground water. The concentration level of zinc is increasing steadily in the environment. Zn2+ is a micronutrient necessary to all living things[1]. The excessive intake of Zn2+ can however be fatal, and it accumulates in the body of the organisms through the food chain via bio-geochemical cycles[2,3]. According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA), Zn2+ has been ranked in the list of toxic heavy metals[4,5]. The limit of discharge of Zn2+ in ground water, fresh water, and estuaries recorded by government agencies of various countries is shown in Table 1. The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act-2007 (CERCLA) has ranked Zn2+ 74th with respect to water pollution[6]. Hussain et al.[7] suggested that the utility, as well as deficiency and toxicity effects of Zn2+, are enough to develop awareness towards maintenance and mitigation of this precious metal.

Table 1. Discharge limit of Zn2+ suggested by various government agencies.

Name of the agency Type of water Discharge

limit (mg·L−1)Ref. World Health Organization (WHO) Drinking water 5 [4,8,9] Minimum National Standards (MINAS), Ministry of Environment and Forest, Government of India Surface water 5 [10] Minimum National Standards (MINAS), Ministry of Environment and Forest, Government of India Potable water 3 [11] Central Pollution Control Board, India Wastewater 5 [12] United States Environment Protection Agency Drinking water 5 The mitigation of heavy metals, including Zn2+ to the optimal level is crucial. To achieve this, several strategies such as physical and chemical techniques have been in use, including ion-exchange[13], ion floatation[14], electro-coagulation/floatation[15,16], electro-deposition[17], irradiation[18], ozonation[19], adsorption though the use of activated carbon[20], precipitation/sedimentation[21], biological operations like microbial fuel cells[22], flocculation[23], filtration through membranes[24], chemical precipitation[25], and solvent extraction[26].

However, all of these methods have proven to be quite effective for the removal of heavy metals but they have many operational difficulties, including the production of concentrated sludge that creates a secondary disposal problem and thus, are considered to be expensive. Therefore, biological processes, such as biodegradation, bioaccumulation, or biosorption, have received increasing interest due to their low cost, effectiveness, ability to produce less or no sludge, and environmental benignity[27].

In the current scenario, biosorption is attracting the attention of environmental researchers. It involves the removal of pollutants from aqueous solution using biological materials or their derivatives. A number of studies have already been published on the biosorption of metals using different biological agents as adsorbents. These include the phytomass of algae, lichens, bryophytes, pteridophytes, angiosperms[28−32], egg shell[33], agricultural waste[34], agro-industrial waste[35], bacteria[27], and fungi[36]. Fungal biomass, due to its excellent biosorptive potential, have been in use as a cheap source of biosorbent, along with some advantages over other conventional adsorbents. Dead mycomass offers excellent utility over a living one due to multiple reasons: (i) no toxicity; (ii) excellent performance in removal of pollutants; (iii) operational ease and low cost; (iv) no requirement for a regular nutrient supply; (v) no production of bio-chemical sludge; and (vi) reusability for numerous cycles.

Recently the mycomass of many fungal species has been tried for metal biosorption, mainly involving the Aspergillus[36], Rhizopus[37], Penicillium[38], Trichoderma aspergillus[39], Streptoverticillum[40], and Sacharomyces[41]. Therefore, the present study was formulated for the biosorption of Zn2+ by dead mycomass of Aspergillus flavus (DAFM). For achieving the maximum removal under a fabricated water-treatment system, the present research aimed to investigate the potential of DAFM to adsorb Zn2+ from its aqueous solution. For the optimization of conditions, the biosorption experiments were performed under different ranges of parameters including contact time, temperature, mycomass dose, mycomass particle size, and initial dye concentration. The effect of pH was not examined because neutral pH (pH = 7.0) has been reported to be effective for Zn2+ removal[36]. The experimental data were evaluated by fitting into different isotherm models. For a better understanding of the nature of Zn2+ biosorption, the experimental data was evaluated via thermodynamic studies. Besides these, to understand the biosorption mechanism, the biosorption data were evaluated using different kinetic models. The functional groups present on the DAFM surface were investigated through FTIR spectroscopy of DAFM, before and after biosorption.

The present investigation was hypothesized for the biosorption of zinc using the biomass of dead Aspergillus flavus mycelia. It is a sustainable and cost-effective strategy for the removal of Zn2+ metal ions from contaminated water. The core hypothesis is that the fungal biomass, owing to the presence of active functional groups such as carboxyl, amine, amide, hydroxyl, phosphate, and amino groups on its cell wall, can effectively adsorb Zn2+ ions through mechanisms like ion exchange, complexation, and chemical and physical adsorption. The objective of this research is to investigate the metal-binding efficiency of DAFM under different environmental and operational parameters, including: DAFM particle size DAFM age, temperature, contact duration, initial zinc concentration, and DAFM dosage. This research also aims to model the biosorption process using adsorption isotherms and kinetic models to understand the nature of metal uptake. Furthermore, it seeks to evaluate the thermodynamic behavior of the process. Overall, the study is directed toward establishing Aspergillus flavus as a viable biosorbent for zinc decontamination in industrial wastewater, offering a greener alternative to conventional remediation techniques.

-

In the present study, the fungus A. flavus, chosen for the preparation of mycomass, was isolated from soil samples[42], and selected on the basis of its dominance for biosorption of Zn2+. The mycelial mycomass of A. flavus was prepared on liquid MGYP medium after sterilization at 15 psi, 121 °C for 15 min. For the preparation of A. flavus mycomass, the inoculum was added to five flasks containing MGYP broth. After 96 h of incubation at 25 ± 2 °C in a BOD incubator shaker, all the flasks were steam sterilized in an autoclave. The dead mycelial mat of A. flavus was then harvested by filtering through a standard sieve. The mycomass was then washed twice with double-distilled water and the obtained mycelial biomass was then placed into a hot air oven for drying at 60 ± 2 °C for 24 h. The dried and dead A. flavus mycomass was then crushed using a mortar and pestle to achieve fine powdered mycomass. The mycomass was then filtered via standard sieves to obtain the mycomass of three different particle size, i.e., 125−250, 250−355, and 355−500 µm.

Preparation of Zn2+ solutions of different concentrations

-

Zinc sulphate powder was added to distilled water to obtain zinc solutions of different concentrations to assess the Zn2+ removal ability of DAFM. The stock solutions of metal (Zn2+) were prepared to obtain different concentrations (100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 ppm) separately.

Biosorption of Zn2+ by DAFM

-

A set of 27 flasks of 250 mL capacity, filled with 100 mL of 100 ppm zinc solution (as zinc sulphate) were used for given mycomass, i.e., DAFM, for determining the effect of mycomass age and particle size on biosorption of Zn2+. The 27 flasks was divided into three subsets, each for different mycomass ages (subset I of 48 h, II for 96 h, and III for 144 h age of DAFM). To the nine flasks of subset I, DAFM was added as follows:

Set 1:

A:

(i) 10 mg DAFM (of 48 h age and 355−500 µm particle size) + 100 ppm zinc sulphate solution: three flasks;

(ii) 10 mg DAFM (of 48 h age and 250−355 µm particle size) + 100 ppm zinc sulphate solution: three flasks;

(iii) 10 mg DAFM (of 48 h age and 125−250 µm particle size) + 100 ppm zinc sulphate solution: three flasks.

Similarly, the DAFM was added to subset II and III as:

B:

(i) 10 mg DAFM (of 96 h age and 355−500 µm particle size) + 100 ppm zinc sulphate solution: three flasks;

(ii) 10 mg DAFM (of 96 h age and 250−355 µm particle size) + 100 ppm zinc sulphate solution: three flasks;

(iii) 10 mg DAFM (of 96 h age and 125−250 µm particle size) + 100 ppm zinc sulphate solution: three flasks.

C:

(i) 10 mg DAFM (of 144 h age and 355−500 µm particle size) + 100 ppm zinc sulphate solution: three flasks;

(ii) 10 mg DAFM (of 144 h age and 250−355 µm particle size) + 100 ppm zinc sulphate solution: three flasks;

(iii) 20 mg DAFM (of 144 h age and 125−250 µm particle size) + 100 ppm zinc sulphate solution: three flasks.

A set of three flasks containing 100 ppm zinc solution, without added DAFM served as control. All flasks were then placed on a rotator shaker at 150 rpm for 20 min. After a contact period of 20 min, the mycomass was separated by filtering the reaction mixture through a Whatman No. 40 filter paper to prevent the probable interference of turbidity and the filtrate was further processed for assessing the concentration of metal remaining in the solution. A few drops of concentrated nitric acid and hydrochloric acid were added in the filtrate for the acidification. Thereafter, the sets of three flasks of a particular particle size within a particular age mycomass were pooled together to achieve a composite solution for atomic absorption spectrophotometery. Before the measurement, the filtrates were diluted with appropriate amounts of double-distilled water. The absorbance of these were recorded on an AA-7000 model atomic absorption spectrophotometer (AAS).

Another set of 15 flasks were used for the determination of optimal contact time for the removal of Zn2+ using DAFM. These 15 flasks were divided into five subsets of three flasks for 20 min, 40 min, 60 min, 80 min, and 1,000 min. A set of 15 flasks (each of three flasks for each of the given contact time) without adding mycomass were utilized as control. All flasks were placed on a rotator shaker at 150 rpm. After 20 min, a set of three flasks were removed as subset A1 to which the suspension was filtered through Whatman filter paper separating the DAFM loaded with Zn2+ ions. The amount of unadsorbed Zn2+ (remaining the solution after biosorption) was recorded on an AA-7000 model AAS in the Department of Botany, Chaudhary Charan Singh University, Meerut (Uttar Pradesh, India). Similarly, each of the subsets of three flasks (A2, A3, A4, and A5) was removed after 40, 60, 80, and 100 min. The procedure for all subsets was repeated after 20 min. Another set of three flasks filled with 100 mL of 100 ppm zinc solution, without DAFM, served as control. The efficiency of DAFM in all flasks was assessed and analyzed as those for the effect of DAFM age and particle size. Similarly, five sets were used for the optimization of temperature, DAFM dose, and initial zinc concentration. To these sets, the experiments and procedures were as follows:

(i) 15 flasks for temperature variable (three for 25 °C, three for 35 ºC, three for 45 °C, three for 55 °C, and three for 65 °C);

(ii) 15 flasks for DAFM dose variable (three for 10 mg, three for 20 mg, three for 30 mg, three for 40 mg, and three for 50 mg mycomass dose); and

(iii) 15 flasks for initial zinc concentrations (three for 100 ppm, three for 200 ppm, three for 300 ppm, three for 400 ppm, and three for 500 ppm).

A set of five flasks filled with 100 mL of 100 ppm zinc solution, without DAFM, served as control for the temperature variable. Another set of five flasks filled with similar content, without adding DAFM, served as the control for the DAFM dose variable. One more set of five flasks filled with different concentrations of zinc (100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 ppm), without adding DAFM, served as the control for initial Zn2+ concentrations. The efficiency of DAFM to all these flasks was evaluated and assessed as those for contact time variable. The Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy of DAFM before (unloaded), and after (Zn-loaded) biosorption was carried out for the confirmation of DAFM surface functional sites involved in Zn2+ biosorption. Before analysis, the samples of DAFM were dried for 24 h at 80 °C. For FTIR analysis, KBr pellets were prepared containing 1.5 mg of the DAFM sample adding 200 mg of KBr. The spectra were recorded on an IR Affinity-1 SHIMADZU spectrophotometer, Sr. no. A21374801220 (at CCS University Meerut, Uttar Pradesh, India) in the range of 4,000 to 500 cm−1.

Calculation of specific Zn2+ uptake by DAFM

-

The specific amount of Zn2+ taken up by DAFM was calculated using the following equation:

$ \mathit{q}\mathit{e}=\dfrac{\mathit{V}\left({\mathit{C}}_{\mathit{i}}-{\mathit{C}}_{\mathit{f}}\right)}{\mathit{W}} $ (1) The adsorption percentage was determined using the following formula:

$ \text{%}\; \mathit{B}\mathit{i}\mathit{o}\mathit{s}\mathit{o}\mathit{r}\mathit{p}\mathit{t}\mathit{i}\mathit{o}\mathit{n}=\dfrac{(\mathit{C}_{\mathit{i}}-\mathit{C}_{\mathit{f})}}{\mathit{C}_{\mathit{i}}}\ \times\ 100 $ (2) where, qe represents the quantity of adsorbed Zn2+ (mg·g−1 mycomass); V is the volume of aqueous zinc solution (L); Ci is initial Zn2+ concentration in aqueous solution (ppm); Cf is the final concentration of zinc solution after biosorption (ppm); W is the added DAFM dose (dry weight in g).

Isotherm models used for the study of Zn2+ biosorption onto DAFM

-

For the analysis of adsorption equilibrium data, three widely applicable isotherm models were used such as Langmuir[43], Freundlich[44], and Tempkin[45]. These models were applied for single solute systems to depict the adsorption equilibria of the DAFM and represented by the following equations:

Langmuir's model:

$ \dfrac{\mathit{C}_{\mathit{e}}}{\mathit{q}_{\mathit{e}}}=\dfrac{1}{\mathit{K}_{\mathit{L}}\mathit{q}_{\mathit{m}\mathit{a}\mathit{x}}}+\mathit{C}_{\mathit{e}}/\mathit{q}_{\mathit{m}\mathit{a}\mathit{x}} $ (3) Freundlich's model:

$ \mathit{L}\mathit{o}\mathit{g}{\mathit{q}}_{\mathit{e}}=\mathit{L}\mathit{o}\mathit{g}{\mathit{K}}_{\mathit{F}}+\dfrac{1}{\mathit{n}}\mathit{L}\mathit{o}\mathit{g}{\mathit{C}}_{\mathit{e}} $ (4) Tempkin's model:

$ {\mathit{q}}_{\mathit{e}}={\mathit{B}}_{\mathit{T}}\mathit{L}\mathit{n}{\mathit{K}}_{\mathit{T}}+{\mathit{B}}_{\mathit{T}}\mathit{L}\mathit{n}{\mathit{C}}_{\mathit{e}} $ (5) where, qe (mg·g−1) for all the three isotherm models indicates the adsorbed amount of adsorbate per unit mass of adsorbent at equilibrium; qmax (mg·g−1) is characteristic feature of Langmuir's model which represent the maximum (monolayered) adsorption capacity of adsorbent to its per unit weight; KL (L·mg−1) is a constant of Langmuir's model which is directly associated to the affinity of functional sites to the pollutant (Zn2+); Ce (mg·L−1) reflects the equilibrium metal concentration; KF is one of the Freundlich's constants which determines whether the conditions are favorable for biosorption and thus, depicts the influence of adsorption process on adsorption capacity; and 1/n reflects one of the impactful constants of Freundlich's model which determines the effect of pollutant concentration on adsorption capacity and thus indicates the intensity of adsorption.

Herein, the determination of some other characteristic constants such as BT (RT·b−1) and KT (L·mg−1) of Tempkin's model can not be denied. BT reflects the heat of adsorption, whereas KT is a constant representing the binding of pollutant to the adsorbent at equilibrium, and corresponds to the maximum energy of the binding process. b (J·mol−1) is another constant of Tempkin's model; R (8.314 J·K−1·mol−1) is universal gas constant; and T is the temperature in celsius[42,46].

Kinetic study of Zn2+ biosorption onto DAFM

-

To interpret the mechanism of adsorption, at pH = 7.0, 100 mL of 50 ppm zinc solution was taken into a set of 27 flasks at 25 °C temperature and 10 mg dose of DAFM was added to these flasks. All these flasks were stirred well at 150 rpm. The sets of three flasks each were removed at intervals of 10 min, until 90 min of the final set. The suspension was filtered and examined for residual Zn2+ concentration through AAS. These findings were proved using contact time studied for interpretation of biosorption kinetics and measurement of residual Zn2+ concentration at equilibrium[20,47]. The adsorption kinetics were investigated via two kinetic models, i.e., pseudo-first order (PFO) and pseudo-second order (PSO) as mentioned in Eqs (6) and (7). These models can be expressed using the following equations:

PFO model:

$ \mathit{L}\mathit{o}\mathit{g}\left({\mathit{q}}_{\mathit{e}}-{\mathit{q}}_{\mathit{t}}\right)=\mathit{L}\mathit{o}\mathit{g}\mathit{I}\mathit{n}{\mathit{q}}_{\mathit{e}}-{\mathit{K}}_{1}\mathit{t} $ (6) PSO model:

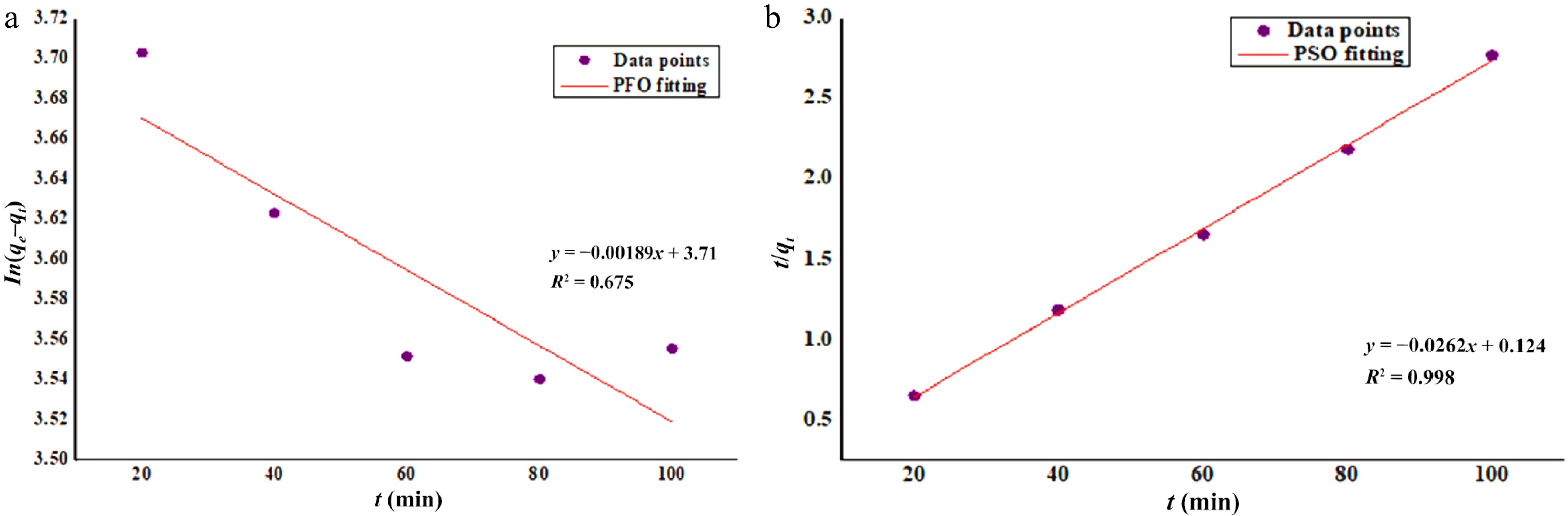

$ \dfrac{1}{{\mathit{q}}_{\mathit{e}}}=\dfrac{1}{{\mathit{K}}_{2}}{\mathit{q}}_{\mathit{e}}^{2}+\dfrac{1}{{\mathit{q}}_{\mathit{e}}}\mathit{t} $ (7) where, qe is the amount of Zn2+ adsorbed per unit weight of DAFM (mg·g−1) at equilibrium; qt (mg·g−1) denoted to the amount of Zn2+ adsorbed per unit weight of DAFM at different 't'; K1 (min−1) and K2 (g·mg−1·min−1) are the characteristic rate constants of PFO and PSO models, respectively. The value of first order rate constant (K1) was derived from the calculations using intercept and slope of graph of In (qe – qt) vs 't' (Fig. 1a). Similarly, the value of second order rate constant K2 was achieved by using intercept and slope of the graph of t/qt vs 't' (Fig. 1b)[20,47].

Thermodynamic study of Zn2+ biosorption using DAFM

-

Thermodynamic study reveals the chemical or physical behavior of adsorption mechanism, hence the adsorption data, derived at different temperatures from 298.15 to 348.15 K, was also assessed through thermodynamic investigation. The calculations for the thermodynamic parameters ∆Go (Gibbs free energy), ∆Ho (standard enthalpy), and ∆So (change in entropy) was carried out using the following equations[48]:

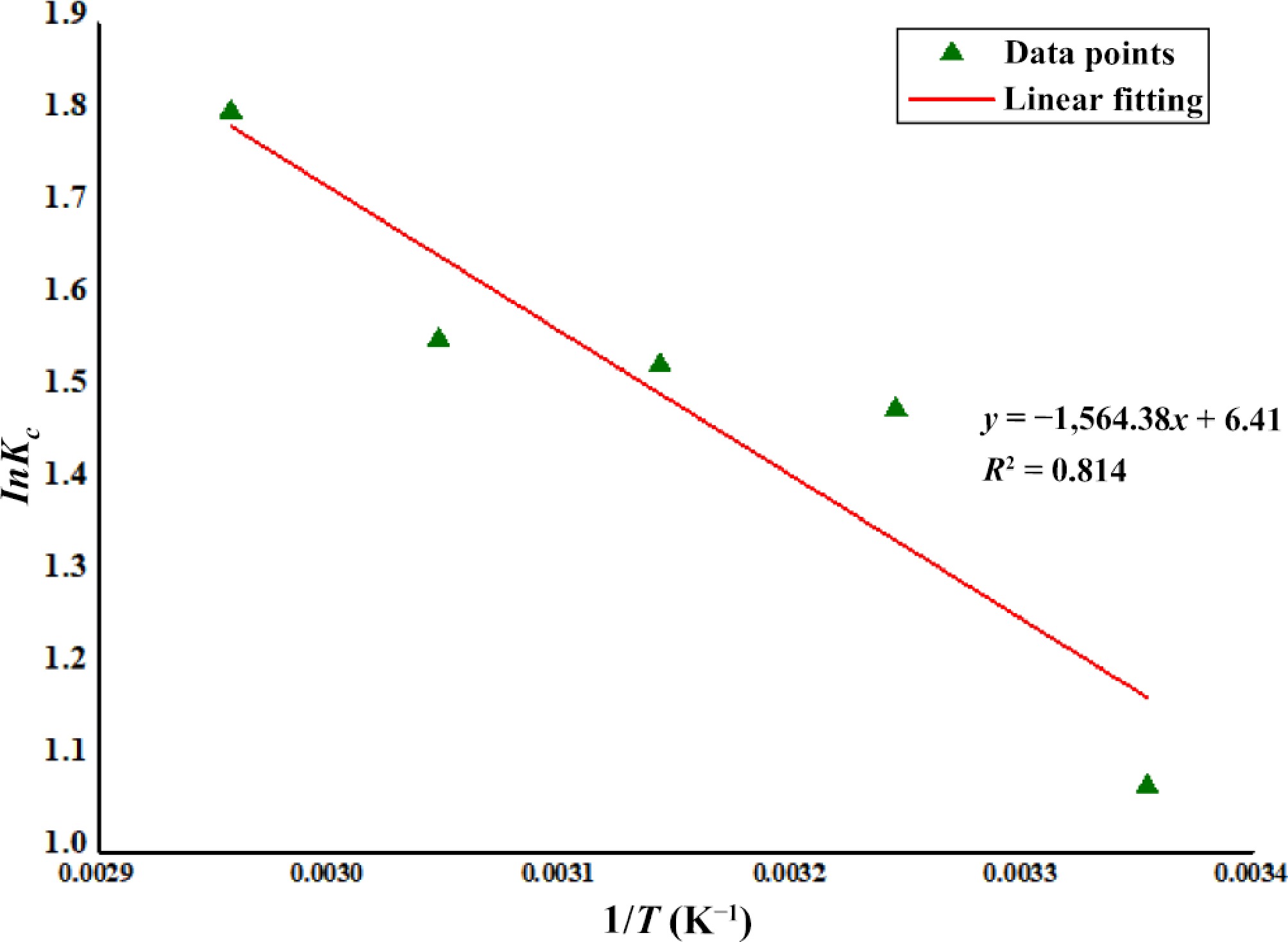

$ \Delta\mathit{G^o}=-\mathit{R}\mathit{T}\mathit{I}\mathit{n}\mathit{K}\mathit{_C} $ (8) $ \Delta\mathit{G^o}=\Delta H^o-T\Delta S^o $ (9) where, R is the universal gas constant (J·mol−1·K−1); T is the indicative of temperature (K); and KC (qe/Ce) represents the equilibrium constant of the mechanism [Eqs (8) and (9)]. The values of ∆Ho and ∆So were obtained using the values of intercept and slope derived from the graphs (Fig. 2) constructed between InKC vs 1/T (K)[48].

Herein, it is also necessary to consider that thermodynamic conditions should be the same (i.e., fixed temperature and pressure) across a system, but in the case of the present investigation, the experiments for Zn2+ biosorption were conducted at different temperatures, i.e., non-standard conditions as well as the pressure were not the parameters studied. Therefore, the thermodynamic parameters [Eq. (9)] might be affected with the change in system environment[47] and hence, can be represented with their signs of activations [Eq. (10)]:

$ \Delta {\mathit{G}}^{\pm }=\Delta {\mathit{H}}^{\pm }-\mathit{T}\Delta {\mathit{S}}^{\pm } $ (10) Using Eq. (9) another equation can also be derived in the form of Eq. (11) as:

$ \mathit{I}\mathit{n}\mathit{K}_{\mathit{C}}=\left(\dfrac{\Delta\mathit{S^o}}{\mathit{R}}\right)-\left(\frac{\Delta\mathit{H^o}}{\mathit{R}\mathit{T}}\right) $ (11) In the same way, Eq. (10) can be re-written in the form of Eq. (12) as:

$ \mathit{I}\mathit{n}{\mathit{K}}_{\mathit{C}}=\left(\dfrac{{\Delta \mathit{S}}^{\text ‡}}{\mathit{R}}\right)-\left(\dfrac{{\Delta \mathit{H}}^{\text ‡}}{\mathit{R}}\right) $ (12) Change in standard enthalpy (∆H±) was represented with its sign of activation. Similarly, the change in entropy was also represented with its activation sign (∆S±). Both ∆H± and ∆S± were obtained using Eq. (12) and verified with the calculations using intercept and slope of the graph constructed between InKC vs 1/T (K) (Fig. 2).

-

Removal of a given pollutant from aquatic solution using a specific adsorbent might have optimal conditions for maximum results. This approach can be assigned to the reason that, the efficiency of any adsorbent might vary with different adsorbates also affected by the system conditions. Thus, it is necessary to investigate the optimal conditions for an adsorbent to be used effectively and economically. Several studies are available suggesting the effects of contact time, temperature, pH, adsorbent amount, and adsorbate concentration etc. on the biosorption of metals/dyes. Keeping in mind the recent findings, the present investigation was focused on the biosorption of Zn2+ by DAFM as well as the optimization of DAFM age, DAFM particle size, contact time, temperature, DAFM dose, and initial Zn2+ concentration for effective biosorption.

Effect of DAFM age and particle size on biosorption of Zn2+

-

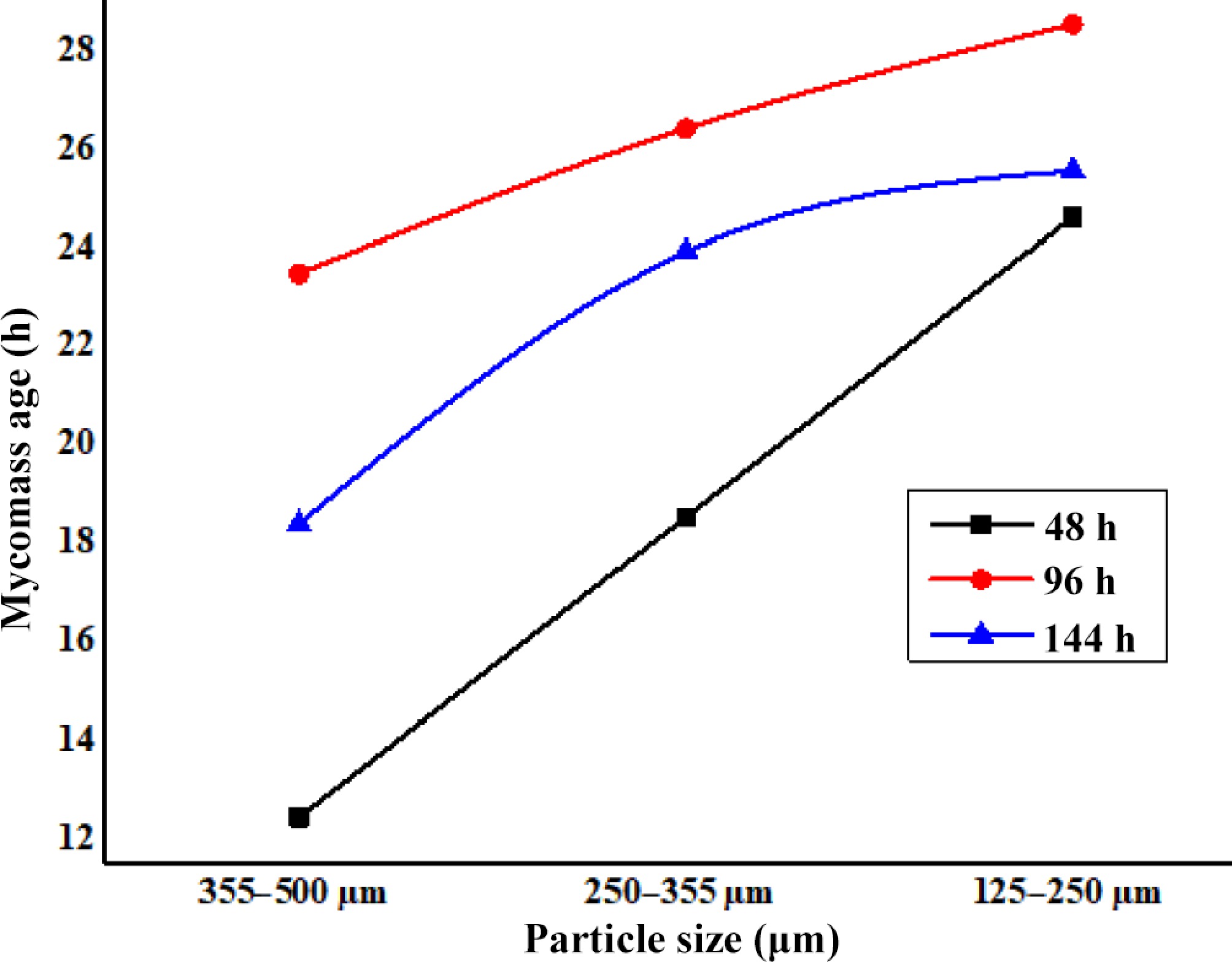

The age and particle size of mycomass particles are crucial features that influence their properties to interact with surrounding pollutant/metal ions in a biosorption process. After the optimization of these two factors, the effective removal of pollutants could be achieved. In this respect, the present study was conducted to adsorb Zn2+ from its aqueous solution using DAFM of different ages (48, 96, and 144 h) and particle size (355–500, 250–355, and 125–250 µm) at 25 °C, pH = 7.0, from 50 mg·L–1 ZnSO4 solution. Figure 3 represents the effect of the age of DAFM and its particle size on biosorption of Zn2+ from its 50 ppm aqueous solution.

Among the mycomass ages, the adsorption capacity of 48 h old DAFM was always lower than those of 96 and 144 h old DAFM (Fig. 3). However, the adsorption capacity of 96 h old DAFM was higher in comparison of other mycomass ages, but the marked difference between 96 and 144 h old DAFM was very little, and thus, could be ignored. At a look at the effect of particle size, the trend was similar that the adsorption capacity of 96 h old mycomass was always higher than those of 48 and 144 h old mycomass with different particle size studied. Thus, concluding from Fig. 3, the maximum adsorption capacity (qe = 28.54 mg·g–1) was obtained with 96 h old mycomass with its 125–250 µm particle size. The performance of 96 h old DAFM could be ascribed as the older mycelium (over 96 h of age) becomes comparatively highly vacuolated than those of younger. With growing age, the fungal mycelium goes to dying and decaying through developing hyphal aggregations[49] as well as distortion of functional groups resulting in decreased capability to adsorb pollutants like metals. The mycomass of younger age was found to have excellent capacity to adsorb the metal in comparison to that of the older ones. Similar effects of mycomass age were investigated by other workers using different mycomass for biosorption of metals[36,50,51].

Figure 3 also depicts the effect of particle size of mycomass on adsorption capacity of DAFM to adsorb Zn2+. The adsorption capacity (qe) was increased from 12.42 to 24.62 mg·g–1 with decreasing particle size from 500−355 to 250−125 µm with 48 h old DAFM. With 96 h old mycomass, the adsorption capacity was increased from 23.48 to 28.54 mg·g–1 at change of particle size from 500−355 to 250−125 µm. The adsorption capacity with 144 h old DAFM was slightly lower than those of 96 h old DAFM, but it was higher than those of 48 h old DAFM. Thus, it is clear that the mycomass of bigger particle size (i.e., 355–500 µm) has yielded the lower removal with all the mycomass ages. On the other hand, the mycomass of comparatively smallest particle size (i.e., 125–250 µm) has yielded the maximum adsorption of Zn2+ ions. The increased adsorption capacity using DAFM of smaller particle size could be due to the increase in total surface area of mycomass which probably has made more adsorption sites available for maximum binding of metals. Additionally, the smaller size of mycomass allowed a quicker uptake of metal ions through the interactions followed by bond formation between metal ions and adsorption sites of the DAFM surface[52]. Moreover, considering the effect of age, the DAFM has yielded the maximum removal of metal with the combination of 96 h age and 125–250 µm particle size. The investigated particle sizes of DAFM under entire mycomass ages revealed that, the performance of smallest particle size (125–250 µm in this work) was excellent at the biosorption of Zn2+ (Fig. 3). Therefore, in the present work, the mycomass of 96 h age and 125–250 µm particle size was selected for further studies on the biosorption of Zn2+ using DAFM.

Effect of contact time on Zn2+ biosorption

-

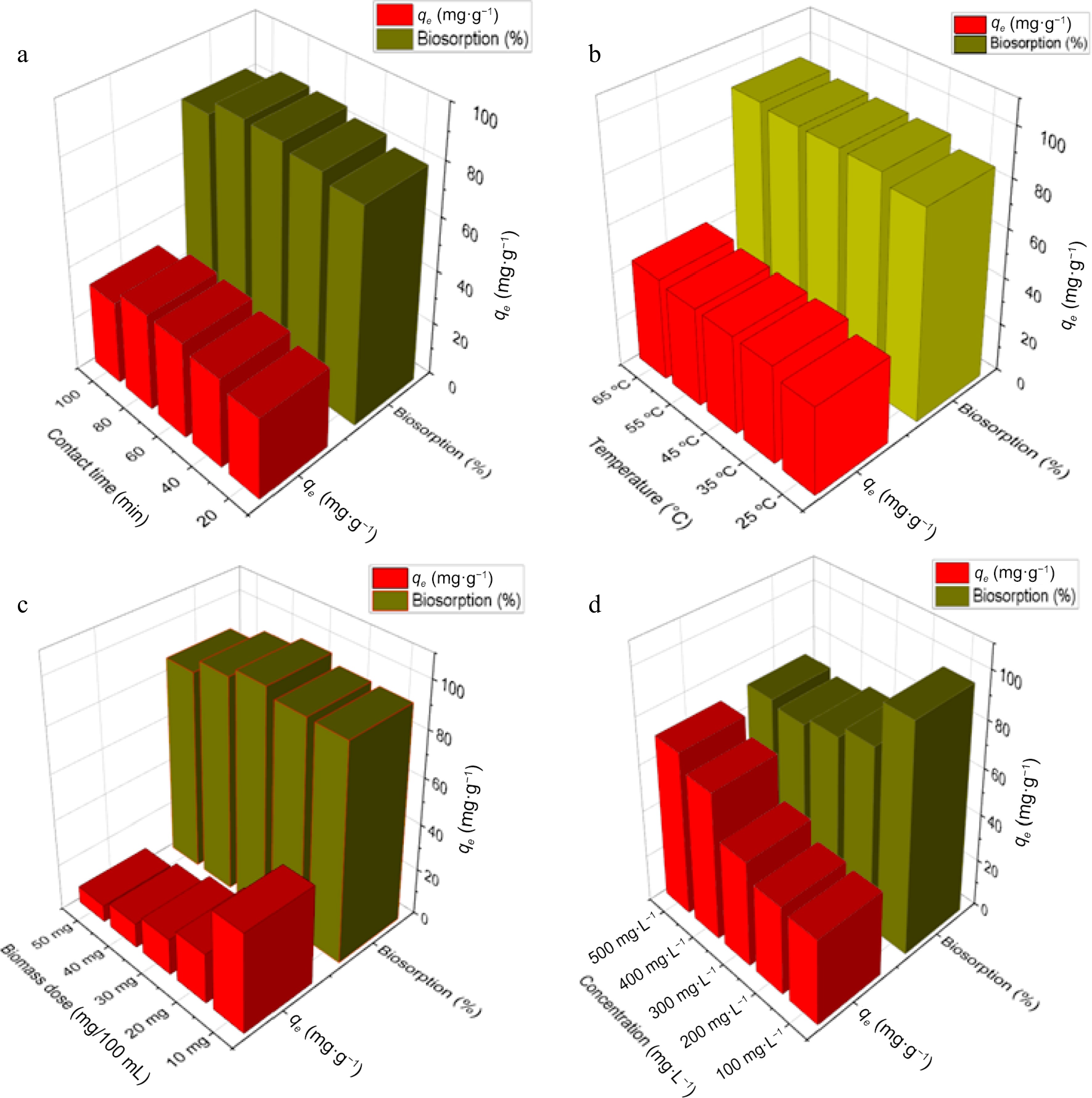

The duration of contact between biomass and adsorbate is also a key factor that affects their interaction and consequent binding. Optimization of contact time is thus, essential for achieving maximum results. Therefore, the present study was conducted working on biosorption of Zn2+ at different contact times (20 to 100 min at a regular interval of 20 min) between Zn2+ ions and DAFM particles in 100 ppm Zn2+ solution using 10 mg/100 mL doses of optimized DAFM age (96 h) and particle size (125–250 µm); and the temperature was kept the same (25 °C) as previous experiments. Figure 4a represents the effect of contact time on the biosorption of Zn2+ onto DAFM in the form of adsorption capacity and percent biosorption. The adsorption capacity went from ascending with increasing contact time from 10 min to 80 min, which later decreased when the contact time was elevated to 100 min. The increased uptake of Zn2+ on DAFM (36.56 mg·g–1) along with the highest adsorption percentage (86.55%) was achieved and equilibrium was practically attained at 80 min contact time. The increased adsorption at longer contact time is likely because the longer contact time allows the facilitation of more functional sites to be active for more binding of Zn2+ ions as reported by recent researchers[46,53]. However, the adsorption capacity was decreased at higher contact times (after 80 min); the concentration of Zn2+ metal ions was not so high which could be attributed either to: (i) the cohering/blending of DAFM particles[46] causing the blockage of functional adsorption sites making those unavailable for Zn-binding; or (ii) the saturation of all the free binding sites on DAFM resulting in single layer (on outer surface) adsorption of Zn2+[36].

Figure 4.

Effect of different parameters on biosorption of Zn2+ by DAFM. (a) Effect of contact time; (b) effect of temperature; (c) effect of DAFM dose; and (d) effect of initial Zn2+ concentrations.

Impact of temperature on Zn2+ removal

-

Temperature is also a parameter that can not be ignored in the determination of adsorption capacity of any adsorbent. In any adsorption-based water-treatment system, an optimal thermal condition is an intense requirement for achieving the maximum results. It influenced the adsorption phenomena due to its effect on mycomass-metal binding complexes through the ionization of cell wall components[53]. Therefore, for the removal of Zn2+ through biosorption using DAFM, the present research was conducted at a wide range of temperatures, viz., 25, 35, 45, 55, and 65 °C (Fig. 4b). During the study of thermal effect, it was observed that the adsorption capacity was increased from 36.56 to 42.94 mg·g−1 on increasing temperature from 25 to 65 °C, hence, the maximum removal was found at 65 °C. The increase in adsorption capacity at each level of increased temperatures can be ascribed to the reason that the temperature provides the required energy which induce the breakdown of certain chemical barriers, thus facilitating the binding of metal ions onto biosorbent surface[54]. Therefore, 65 °C was considered as one of the components of optimal temperature for this study.

Effect of DAFM concentration

-

Figure 4c delineates the effect of mycomass amount on DAFM's equilibrium on Zn2+ uptake from 100 ppm ZnSO4 solution at optimized contact time and temperature. Different dosages of DAFM were tried such as 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 mg. The maximum Zn2+ ions removal was recorded with 30 mg/100 mL DAFM dose. Further increase in DAFM dose has resulted in decreased percentage as well as adsorption capacity. The maximum percent removal of Zn2+ was 96.92% with adsorption capacity qe = 15.64 mg·g−1. Decrease in adsorption percentage at the DAFM dose beyond 30 mg/100 mL can be attributed to higher density of adsorption sites interfering with one another resulting in a gradual decline in percent removal. It can be the result of reduction in the ration of interfering metal ions with mycomass particles.

Effect of initial strength of Zn2+ ions on the adsorption capacity of DAFM

-

The strength of metal ions can alter the metal removal efficiency through a set of factors such as the availability of specific surface functional groups and the ability of surface functional groups to bind metal ions. Initial concentration of solution can provide an important driving force to overcome the mass transfer resistance of metal between the aqueous and solid phases. The biosorption of Zn2+ onto the DAFM surface was found decreasing with increasing Zn2+ ion concentrations under study. Figure 4d delineates that the maximum percentage removal (96.92%) was attained at 100 ppm Zn2+ concentration while the maximum adsorption capacity was achieved at 500 ppm Zn2+ concentration. With the increased concentration of Zn2+ metal ions, its adsorption increased. The maximum removal 71.04% of 500 mg·L−1 of Zn2+ was obtained after 80 min of contact period while removing 96.92%, 77.82%, 72.59%, and 68.96% respectively for 100, 200, 300, and 400 ppm. The adsorption percentage moved from a successive decline upto the 400 ppm zinc concentration which further increased a little at 500 ppm, as such, the adsorption capacity was highest at 500 ppm Zn2+ concentration which was calculated as qe = 70.13 mg·g−1. The decreasing trend of percent removal with elevating metal concentration can be ascribed due to one of the reasons either: (i) at lower metal concentrations, the metal ions in the aqueous medium would interact with the binding sites of DAFM and left unadsorbed in the solution due to the electrostatic repulsion and/or saturation of binding sites as reported by Jalija et al.[55] and Ong et al.[56]; or (ii) at higher concentrations the number of empty functional sites decreased, thereby tending to decrease in adsorption percentage. Contrary to this, increasing the adsorption percent beyond 400 ppm Zn2+ concentration might be caused by the agglomeration of metal ions due to increased driving forces to overcome all mass transfer resistance of metal ions between liquid and solid phase, resulting in maximum chances of collision between metal ions and mycomass[57,58].

-

For accurate analysis of adsorption capacity and equilibrium behavior of DAFM[50], the adsorption data was examined with three of the universal isotherm models, viz., Langmuir[43], Freundlich[44], and Tempkin[45] isotherm models. The isotherm models are mathematically utilized to describe the relationship between the concentration of solute in the aqueous solution and the amount of solute adsorbed onto solid surface of the mycomass. For the investigation of isotherm, the adsorption data was analysed at different metal concentrations such as 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 ppm.

LIM

-

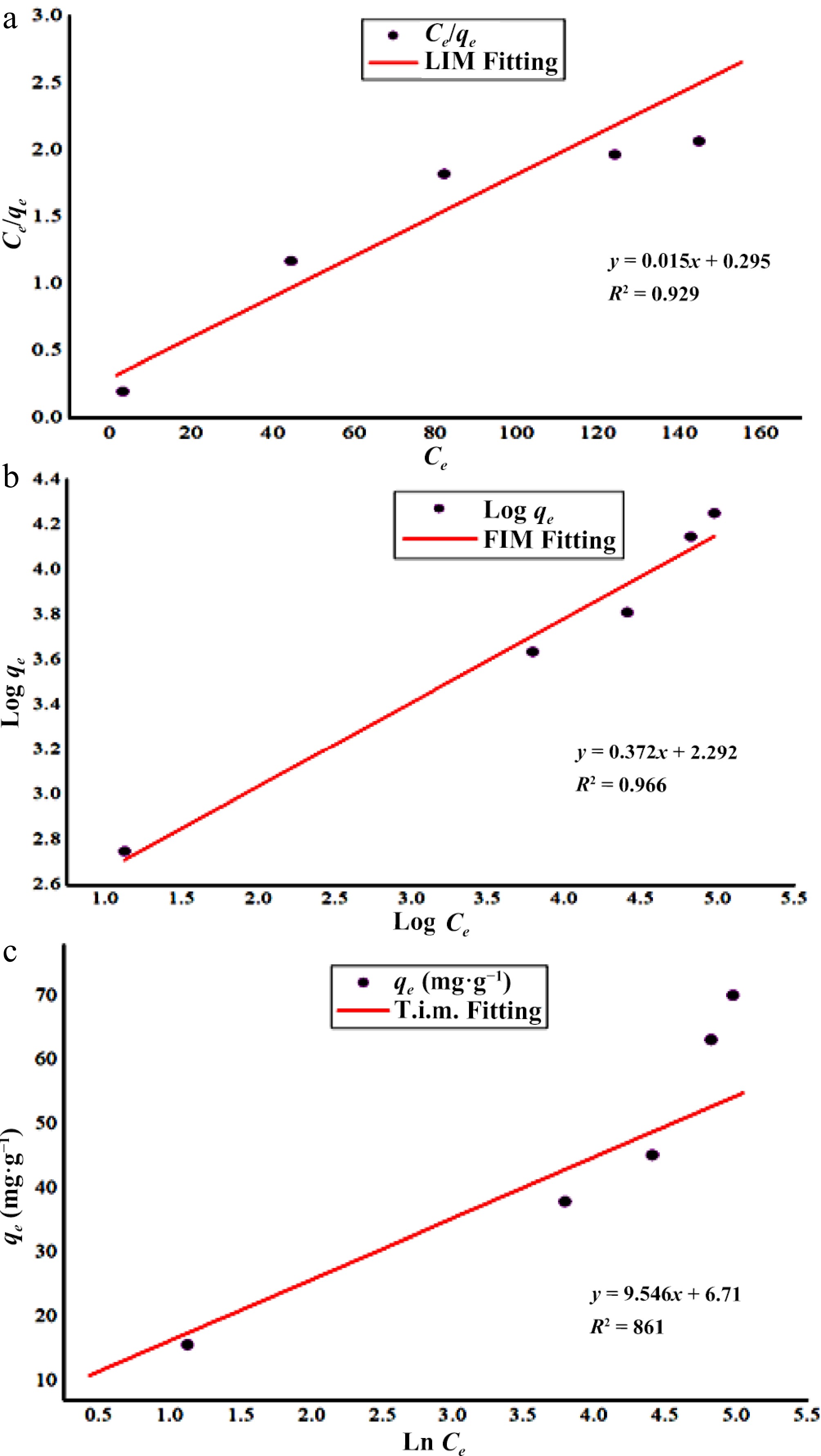

For its reliability and versatility, the Langmuir isotherm model is widely applied in adsorption studies. It represents the homogenous sorption mechanism and relied on the concept of monolayer adsorption. According to Langmuir's model the force between adsorbed ions are not significant and that a limited number of active sites are present on the adsorbent's surface. Therefore states that, once metal ions adsorbed at adsorbent's surface, these occupy the functional sites and hence, no further adsorption occur. Figure 5a represents the graph plotted Ce/qe vs Ce at varied metal concentrations. At 500 ppm initial Zn2+ concentration, the maximum adsorption capacity (qmax) of DAFM was 65.79 mg·g−1 with correlation coefficient R2 = 0.929, which suggests the monolayer adsorption of zinc metal forming a complete single layer of metal on DAFM surface. The maximum adsorbed capacity (qmax = 65.79 mg·g−1) of the metal is close to the value obtained experimentally (qe = 70.13 mg·g−1) and thus, it is comparable indicating the fitness of the model to the experimental data. The binding affinity constant of Langmuir's model (KL = 0.051 L·mg−1) was calculated using the intercept of the graph (Fig. 5a and Table 2) which indicated a higher affinity of metal ions toward the adsorption sites of DAFM[59−61]. The adsorption of Zn2+ onto DAFM was chemisorption, as indicated by qmax and KL.

Figure 5.

Isothermic study of Zn2+ biosorption onto DAFM. (a) Langmuir's isotherm; (b) Freundlich's isotherm; and (c) Tempkin's isotherm.

Table 2. The values of parameters of different isotherm models studied for biosorption of Zn2+ onto DAFM.

LIM FIM TIM qe (exp.) (mg·g−1) = 70.13 qmax (mg·g−1) = 65.79 KF (L·mg−1) = 196.47 BT (J·mol−1) = 9.55 KL (L·mg−1) = 0.51 1/n = 0.37 KT (L·mg−1) = 2.0 R2 = 0.929 R2 = 0.966 R2 = 0.861 FIM

-

The empirical form of Freundlich's equation relies on multilayer formation of adsorbate on the heterogeneous surfaces of biosorbents in which the biosorbent surface is enriched with heterogeneously dense functional sites. The parameters calculated for Freundlich's model by employing its linear form are given in Table 2 and Fig. 5b. Freundlich isotherm parameters were calculated using the intercepts and slope of the plot between log qe and log Ce. For the Freundlich's isotherm model, the adsorption is considered promising if value of KF is found in range of 1–20[62], but the results reveal in the present research that, KF was 196.47 mg·L−1 for linearity of the model which indicated that the biosorbent is highly capable of removing Zn2+ ions from aqueous solution as also the process is physisorption[63]. The adsorption intensity represented by 1/n indicates fitness of this model for biosorption if value of 1/n is in the range of 0 to 1, which in the present study was beyond the unity (1/n = 2.68) indicating the high suitability of DAFM for Zn2+ removal under studied conditions[64] as well as the unfavorable and irreversible process. This value of 1/n (2.68) also indicated stronger interaction between the adsorbent and the adsorbate and the adsorption capacity is only slightly suppressed at lower equilibrium concentrations[64,65]. The value of R2 (0.966) obtained from the plot is significant, representing good fitness as well as the best fitting of this model for biosorption of Zn2+ onto DAFM over other isotherm models under study.

TIM

-

Tempkin isotherm determines the heat of the sorption process and thus utilized to understand the mechanism of adsorption. This model helps in the prediction that the equal distribution of binding energies tied to surface adsorption, therefore, provides accurate knowledge about the process. It is based on the assumption that, the decline in heat related to the biosorption, increases linearly with increasing coverage of adsorbent's surface. A plot of qe vs log Ce (Fig. 5c and Table 2) delineates the determination of isotherm constants BT and KT calculated from the slope and intercept of the graph, respectively. The equilibrium binding constant (KT) represents the maximum binding energy of the process, and the other constant BT represents heat of the particular adsorption experiment[66]. Figure 5c suggests that the linearity of the Tempkin model was not found to be suitable with a positive value of the binding energy constant (KT = 2.0 L·mg−1). The magnitude of BT (9.55 J·mol−1) indicated the process as chemisorption. The correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.861) generated by the plot (Fig. 5c) and the Tempkin equilibrium constants indicated that this model does not satisfy the experimental data[67].

Table 2 represents the model fitness which provides the comparison based on correlation coefficient values along with the constants for each isotherm model. As a perusal of the graphical representation of each of the used isotherm models (Fig. 5a−c), the Freundlich model with a maximum value of correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.966) best describes the removal of Zn2+ ions. Besides this, the adsorption intensity is less than unity (1/n = 0.37), suggesting the favorability of the process[67,68]. The maximum adsorption capacity obtained by Freundlich's model (qmax = 65.79 mg·g−1) is close to the adsorption capacity calculated from experimental data (qe = 70.13 mg·g−1). On the other hand, the value of the high affinity constant (KF = 196.47 L·mg−1) indicated the favorability of DAFM to remove Zn2+ ions and suggested the process is a physical adsorption.

-

Predicting the dynamics of the adsorption mechanism and understanding the factors governing the rate of the adsorption process needs to employ kinetic study, especially the utilization of PFO and PSO models to the biosorption data. Kinetic study also determines whether the process is a physisorption or chemisorption to which the authentication derived from comparison of correlation coefficients, since the authenticity and reliability of the biosorption mechanism for both the kinetic models is expressed in the form of values of correlation coefficients (R2). In Fig. 1 and from Eq. (6), the slope of the graph T (time) vs In(qe−qt) suggests the rate limiting constant (K1) and the intercept gives the adsorption capacity (qe (cal.), mg·g−1). From Fig. 1a, b and Table 3, it is clear that, the value of correlation coefficient of PSO is higher (R2 = 0.998) in comparison of PFO (R2 = −0.238) indicated the adsorption rate-limiting step of the process is a chemical interaction accomplished between functional sites of DAFM and Zn2+ ions. Also, the value of the correlation coefficient of PFO is comparatively very low, indicating that the rate-limiting step in the biosorption process was purely through the chemical interactions instead of the physical process[69]. It was also found that the derived value of K2 (0.01 g·mg−1·min−1) was higher than that of K1 (1.89 × 10−5 g·mg−1·min−1) which also gives the confirmation about chemisorption process. This mechanism behavior indicated that the retention of Zn2+ ions onto the DAFM surface was through two successive seminal stages: (i) first step involve the binding of Zn2+ ions to the primarily exposed functional sites of DAFM due to their maximum chances to join each other; and (ii) the retention of Zn2+ ions can be due to the stabilization of the complex formed in the first step takes place through the chemical bonds with another superficial groups[70]. Based on the calculations of these two parameters, it can be attributed that the main rate-limiting step is the chemical adsorption. The PFO does not fit the adsorption data as observed from the correlation coefficient and rate-limiting component, while the PSO fits well to the adsorption data which suggests that the solute transfer is accomplished by mass transfer, which might be followed by surface adsorption, external diffusion, and/or intra-particle diffusion[71−74].

Table 3. Values of kinetic parameters for biosorption of Zn2+ onto DAFM.

PFO PSO qe (exp.) (mg·g−1) = 70.13 qe (cal.) (mg·g−1) = 42.52 qe (cal.) (mg·g−1) = 38.21 K1 (g·mg–1·min−1) = 1.89 × 10–5 K2 (g·mg−1·min−1) = 0.01 R2 = 0.675 R2 = 0.998 -

The analysis of thermodynamic parameters, which include the change in biosorption enthalpy (∆H‡), Gibbs free energy (∆G‡), and entropy ((∆S‡), has been investigated at different temperatures. The values of ∆H‡ and ∆S‡ were calculated using intercept and slope of the graph of InKC vs 1/T (Fig. 2). Increased value of ∆H‡ indicates the temperature assisted process and can be further induced by rising temperature. Contrary to this, a negative value of ∆G‡ could be ascribed that the adsorption mechanism is spontaneous and its magnitude increases proportionally with the rise in temperature[75]. Some of the studies explored have opined that these parameters are relatively beyond the dependency of temperature and hence, can be considered with reliable accuracy. A study conducted by Ortiz-Oliveros et al.[76] has suggested the slight dependency of these two parameters to temperature. This has led to the proposal of thermodynamic relationship between ∆H‡ and ∆S‡.

For the present investigation the magnitude of thermodynamic parameters enthalpy (∆H‡), Gibbs free energy (∆G‡) and entropy (∆S‡) are given in Table 4. The table demonstrates that the values of free energy were negatively increasing with increasing temperatures (from −15.88 to −18.01 kJ·mol−1) for the biosorption of Zn2+ ions onto DAFM, which indicates the spontaneity of the adsorption mechanism that was proportional to temperature[65]. It also enlightens the opinion that more functional groups on DAFM surface became activated at elevating temperatures, allowing the energy barrier to overcome the hindrance[77,78]. The magnitude of entropy (∆S‡= 53.29 J·K−1·mol−1) is higher than the enthalpy (∆H‡= 13.01 kJ·mol−1), and the higher magnitude of entropy change can be attributed to the increased degree of freedom of the released metal ions during the exchange of ions originating from the DAFM surface[79]. These findings also indicate an increased randomness at the solid-liquid interface for the adsorption of metal ions onto DAFM caused by the higher affinity of the adsorbent towards Zn2+ ions. Also the positive magnitude of change in enthalpy (∆H‡= 13.01 kJ·mol−1) indicate the endothermic adsorption of Zn2+ onto DAFM. Similar findings were found in an another study of Cu(II) biosorption using biochar derived from algal biomass, the calculated parameters gave the affirmation of a spontaneous and feasible process[78]. Concluding the magnitudes of calculated thermodynamic parameters it is feasible to say that the biosorption of Zn2+ ions onto DAFM is endothermic, spontaneous and more favorable at high temperature[79].

Table 4. Calculated thermodynamic parameters for Zn2+ biosorption onto DAFM.

Adsorbent T (K) ΔG‡

(kJ·mol−1)ΔH‡

(kJ·mol−1)ΔS‡

(J·K−1·mol−1)Correlation coefficient DAFM 298.15 −15.88 13.01 53.29 R2 = 0.814 308.15 −16.41 318.15 −16.94 328.15 −17.48 338.15 −18.01 Some recent studies indicating the biosorption potential of different adsorbent materials (of biological or non-biological origin) for the biosorption of Zn2+ are summarized below in Table 5. The table gives a comparative view of those adsorbents with the present investigation suggesting the usability of DAFM for the removal of Zn2+ over other adsorbents.

Table 5. Comparable potential of some adsorbents for Zn2+ biosorption in recent years.

Adsorbents Zn2+ removal %/

uptake (mg·g−1)Ref. Graphite-iron alloy 72.5% [79] Penicillium sp. 52.14 mg·g−1 [80] Aspergillus terreus 10.7 mg·g−1 [81] Microcystis aeruginosa 67 mg·g−1 [82] Gauva leaves 14.5 mg·g−1 [65] Aspergillus terreus 10.7 mg·g−1 [81] Tinospora cordifolia 87% [83] Agaricus biosporus biomass 19.61 mg·g−1 [84] Inula viscosa leaves 85% [20] Lantana camara leaves 2.778 mg·g−1 [85] Walnut carbon nanoparticles 90% [86] Sargassum myriocystum 86.67% [87] Spirulina platensis 50.7 mg·g−1 [78] Reynoutria japonica 17 mg·g−1 [88] Dalbergia sissoo sawdust 6.36 mg·g−1 [89] Pithophora cleveana 13.58 mg·g−1 [90] Groundnut husk ash 80.00% [91] Penicillium simplicissimum 1.25 mg·g−1 [92] DAFM 70.13 mg·g−1 Present study -

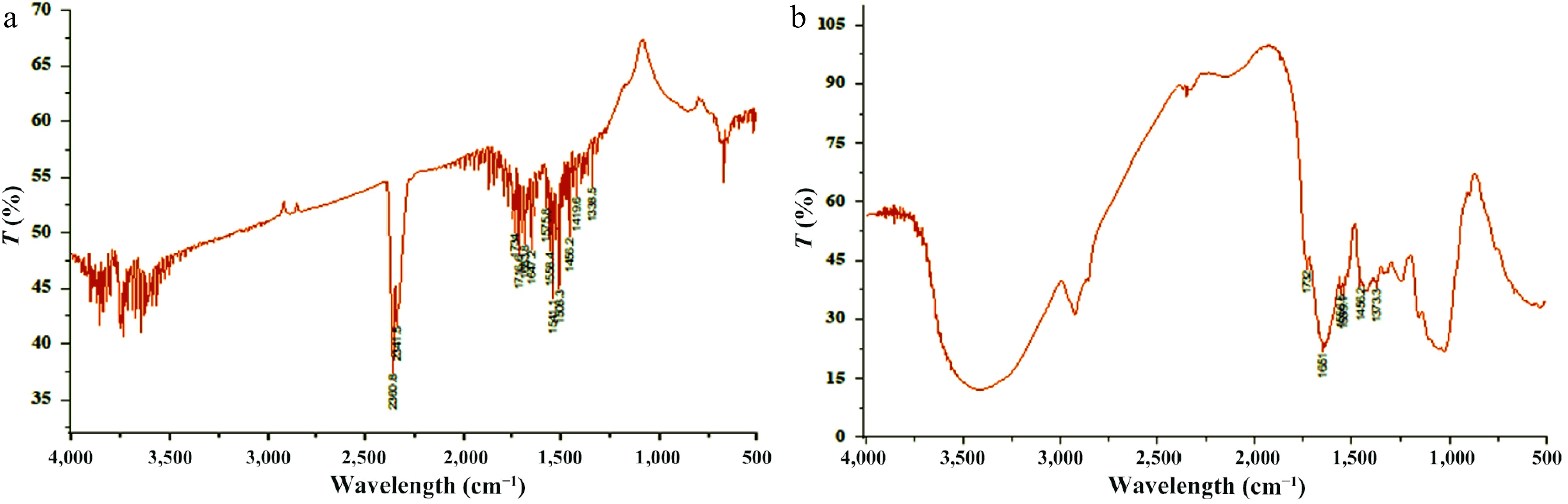

The DAFM was examined before and after the biosorption of Zn2+ and the functional groups of mycomass responsible for removal of metal were identified with IR Afnity-1 Shimadzu spectroscopy at the Department of Botany, Choudhary Charan Singh University, Meerut, Uttar Pradesh, India. It is visible from Fig. 6 and Table 6 that there were many functional groups involved in the biosorption of Zn2+. Before biosorption (Fig. 6a) of metal, the mycomass surface was found to have 13 sharp peaks containing 45 functional groups of 25 types. The peaks contain different functional groups as follows: C-CH3 (1:1385.5), aromatic azo (1:1385.5 and 1:1419.6), sulphate (1:1385.5), alcohol (1:1385.5), sulfonyl chloride (1:1385.5), phenol (1:1385.5), CH2 (1:1419.6), CH3 (1:1419.6), carboxylic acid (1:1419.6, 1:1683.8, 1:1716.6, and 1:1734), aromatic ring (1:1456.2 and 1:1508.3), alkane (1:1456.2), nitro (1:1508.3, 1:1541.9, 1:1558.4, and 1:1575.8), aliphatic azo (1:1541.9, 1:1558.4, and 1:1575.8), aromatic/hetero ring (1:1558.4 and 1:1575.8), amide (1:1558.4, 1:1575.8, 1:1647.2, and 1:1683.8), alkene (1:1647.2), ketone (1:1647.2 and 1:1683.8), C=C (1:1647.2), C=N (1:1647.2), imine (1:1683.8), urethane (1:1716.6), aldehyde (1:1716.6 and 1:1734), ester (1:1716.6 and 1:1734), aliphatic ester (1:2341.5), and pH (1:2341.5 and 1:2360.8).

After biosorption of Zn2+ the number of sharp peaks was reduced to 6. The visible peaks were laden with 22 functional groups of 18 types, showing the involvement of 22 functional groups in the biosorption of the metal. Visible peaks after biosorption (Fig. 6b) contain functional groups as follows: C-CH3 (1:1373.3), aromatic azo (1:1373.3), alcohol (1:1373.3), phenol (1:1373.3), carboxylic acid (1:1373.3, 1:1651, and 1:1732), aromatic ring (1:1456.2), nitro (1:1539.1 and 1:1556.5), aliphatic azo (1:1556.5), aromatic/hetero ring (1:1556.5), amide (1:1556.5 and 1:1651), ketone (1:1651), C=C (1:1651), C=N (1:1651), imine (1:1651), alkene (1:1651), ester (1:1732), aliphatic ester (1:1732), and aldehyde (1:1732).

The aforementioned data reflects the involvement of 20 functional groups of 15 types. Of those, nine groups of seven types such as − aromatic azo (1), sulphate (1), sulfonyl chloride (1), nitro (1), aliphatic azo (2), aromatic/hetero rings (1) and amide (2) were identified as strong binders, and eight functional groups of seven types including carboxylic acid (2), aromatic ring (1), nitro (1), ketone (1), urethane (1), aldehyde (1) and ester (1) − were moderate binders. Besides those two groups i.e., C−CH3 and P−H were found to make weak bonds with Zn2+ ions.

The reduced number of sharp peaks is the indication of the vanishing of seven peaks and thus, confirmed the involvement of their functional groups in the removal of metal. On the other hand, the shift of peaks from 1,385.5 to 1,373.3 cm−1 showed the involvement of S=O stretch and was attributed to the C=O bending vibration of carboxyl group; from 1,541.9 to 1,539.1 cm−1 of N=N stretching of proteins; from 155.4 to 1,556.5 cm−1 of N−O stretch and N−H bend; from 1,647.2 to 1,651 cm−1 of N−H bend of amine group and C=O stretch[81,93], and 1,734 to 1,732 cm−1 C=O stretch[94,95]. Besides those, the vanished peaks such as 1,419.6, 1,508.3, 1,575.8, 1,683.8, 1,716.6, 2,341.5, and 2,360.8 cm−1 have confirmed the involvement of S=O stretch, C−C stretch, N−O stretch, N−H bend[47], N=N stretch, C=O stretch, C−H bend, and stretching vibrations. Such kind of characteristic can be ascribed due to the result of alignment Zn2+ ions with active functional sites of DAFM which caused the change in vibration frequency. The functional groups underneath the wavelengths of vanished peaks as well as the groups of altered peaks, were assumed to be actively participating in the removal of metal ions. The biosorption of metal through the chemical bonds has indicated a chemisorption process. Moreover, the positive charged metal ions might be able to bind with negatively charged functional sites present in the form of hydroxyl, carboxyl, amino, phosphate nitro, and halide groups on the DAFM surface via electrostatic forces[81,96]. Since lipid and polysaccharides contents of the fungal cell wall possess varied charged functional sites that make the feasibility of strong attraction to positively charged Zn2+ ions to bind with mycomass surface.

Table 6. Functional groups of DAFM before and after biosorption of Zn2+ and the involved functions groups with relevant stretching or bending/vibrations.

Functional groups Before biosorption After biosorption Functional groups involved in biosorption Stretching/

bending/

vibrationC−CH3 1 1 − − Aromatic azo 2 − 2 C−C stretch Sulfate 1 − 1 S=O stretch Sulfonyl chloride 1 − 1 S=O stretch Alcohol 1 1 − − Phenol 1 1 − − CH2 1 1 − − CH3 1 − 1 C=O stretch Carboxylic acid 5 3 2 C=O stretch Aromatic ring 2 1 1 C−C stretch Alkane 1 1 − − Nitro 4 2 2 N−O stretch Aliphatic azo 3 1 2 N=N stretch Aromatic/hetero rings 2 1 1 C−C stretch Amide 4 2 2 N−H bend Ketone 2 1 1 C−C stretch vibration C=C 1 1 − − C=N 1 1 − − Alkene 1 1 − − Imine 1 1 − − Urethane 1 − 1 N−H stretch Aldehyde 2 1 1 C=O stretch Ester 2 1 1 C=O stretch Aliphatic ester 1 1 − − P−H 2 − 2 C-H stretching vibration Total 44 of 25 types 23 of 19 types 21 of 15

types− -

The present study demonstrated the significant potential of DAFM for its utilization as a sufficient myco-biosorbent for the biosorption of Zn2+ metal ions from aqueous solutions under specific optimized conditions. A series of various process factors such as DAFM age and particle size, contact time, temperature, DAFM dose, and initial Zn2+ concentration were examined and optimized for the maximum sorption capacity of this myco-biosorbent. The maximum zinc (Zn2+) biosorption was achieved using fungal biomass aged 96 h, with a particle size range of 250–125 µm. This maximum uptake occurred within 80 min of contact time at a temperature of 65 °C, using a dose of 30 mg/100 mL of dried Aspergillus flavus biomass from a 500 ppm Zn2+ solution. The biosorption efficiency varied across different experimental conditions, reflecting the influence of multiple physicochemical parameters. This variation is primarily attributed to the structural and chemical properties of the fungal cell wall, which is rich in polysaccharides, proteins, and a variety of functional groups. FT-IR spectroscopy analysis of DAFM, conducted before and after biosorption, confirmed the presence of functional groups involved in binding metal ions. These groups facilitate metal ion interaction through mechanisms such as complexation and ion exchange, contributing to the overall biosorption capacity of the fungal biomass. The study of the impact of particle size on biosorption of Zn2+ has resulted in the foundation that it can be applicable to the industrial level. Moreover, the DAFM surface possesses a series of mechanisms including physical and chemical adsorptions, biomeneralization, and biotransformation; as also anionic functional molecules to remove the metal ions. Isothermic evaluation revealed that the Freundlich's isotherm model provided the best fit for the experimental data, suggesting a heterogeneous surface and multilayer adsorption of Zn2+ ions onto the DAFM. Kinetic studies were best described by the pseudo-second-order model (R2= 0.998), implying that the rate-limiting step involved chemical interactions between the Zn2+ ions and the functional groups on the DAFM surface. Thermodynamic analysis indicated that the biosorption of Zn2+ onto DAFM was a spontaneous and endothermic process within the studied temperature range. The positive value of entropy change suggested an increased randomness at the solid-liquid interface during biosorption. These findings highlight DAFM as a promising, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly biosorbent for Zn2+ removal from contaminated water. The optimized conditions and the elucidated biosorption mechanisms provide valuable insights for the development of sustainable water treatment technologies. Further research could focus on the regeneration and reusability of DAFM, as well as its performance in more complex multi-metal contaminated water matrices, to enhance its practical applicability. The modifications of the Aspergillus flavus strain through genetic engineering for the specific industrial levels can be helpful to raise it as the most applicable myco-biosorbent for the future.

-

Not applicable.

-

The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: writing original draft, collecting relevant literature, finalization of experiments, writing-review, and editing: Kumar A, Singh R; analysis, supervision, and conceptualization: Tyagi A, Kumar P; mathematical computation and validation of equations: Kumar P. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Kumar A, Singh R, Tyagi A, Kumar P, Kumar P. 2025. Biosorption of zinc ions (Zn2+) by dead Aspergillus flavus link mycomass: isotherm, kinetics, and thermodynamic studies. Studies in Fungi 10: e018 doi: 10.48130/sif-0025-0018

Biosorption of zinc ions (Zn2+) by dead Aspergillus flavus link mycomass: isotherm, kinetics, and thermodynamic studies

- Received: 30 April 2025

- Revised: 25 July 2025

- Accepted: 05 August 2025

- Published online: 09 September 2025

Abstract: The present study explores the potential of dead Aspergillus flavus mycomass (DAFM) as an effective, eco-friendly, and low-cost myco-biosorbent for the removal of Zn2+ ions from contaminated aqueous environments. DAFM, characterized by its chemically diverse surface and abundance of functional groups, offers significant promise for the removal of metal ions. The study systematically optimized key operational parameters − including biomass age, particle size, temperature, contact time, DAFM dosage, and initial Zn2+ concentration − to identify the most favorable conditions for maximum biosorptive efficiency. Advanced characterization techniques, including FT-IR spectroscopy, confirmed the active participation of functional moieties such as hydroxyl, carboxyl, and amide groups in Zn2+ binding, underscoring the role of physicochemical interactions in the adsorption process. The maximum adsorption capacity (qmax = 65.69 mg·g−1) obtained with Langmuir's isotherm model exhibited a close relationship with experimental adsorption capacity. Kinetic analysis supported the pseudo-second-order model, indicating chemisorption as the dominant mechanism, while thermodynamic evaluation revealed that the process is spontaneous and endothermic, with increased randomness at the solid-liquid interface. Furthermore, equilibrium modeling demonstrated the system's conformity to the Langmuir isotherm, highlighting the monolayer adsorption capacity of DAFM. Overall, the findings affirm the potential utility of DAFM in industrial effluent treatment, particularly in sectors releasing zinc-laden wastewater. This study lays the groundwork for scalable applications of fungal biomass in biosorption technologies, contributing to the development of sustainable and cost-effective water purification systems suitable for use in resource-limited settings.

-

Key words:

- Biosorption /

- Metal /

- Zinc /

- Aspergillus flavus /

- DAFM /

- FTIR /

- Isotherm /

- Kinetics /

- Thermodynamics