-

Cocoa, the main source of chocolate, is one of the leading estate commodities for many tropical climate countries, including Indonesia. Millions of people, farmers, and their families rely on cacao cultivation for their livelihood[1]. In Indonesia, the majority of cacao trees are planted by smallholder growers. However, the cultivation area has gradually decreased in the last ten years, from 1,740,612 ha in 2013 to 1,421,009 ha in 2022[2]. Cacao trees are one of the perennial crops that often suffer significant losses due to pests and diseases attacking at all growth stages of the crop[3−5]. In some instances, however, seedlings may become vulnerable to pest attacks and pathogen infection, including by ambrosia beetles (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae)[6,7].

Ambrosia beetle is one of the most crucial beetles infesting cultivated trees, plant nurseries, and forests, and is widely distributed around the world in tropical and subtropical climate countries[8−11]. The beetles typically inhabit and penetrate the xylem wood tissue of host plants and complete their life cycle living in galleries. In addition, to complete their life cycle, the beetles have a beetle-fungi association, which means the presence of some of the fungal associates plays a crucial role in nutritional factors as a major food source for larvae to complete their development[12−15]. In some cases, the fungal associates may be phytopathogenic[16]. However, it is unclear whether they are phytopathogenic, particularly to cacao, and therefore more studies of the ambrosia beetle-fungus relationships are needed.

Xylosandrus compactus (Coleoptera: Curculionidae: Scolytinae) is the most prevalent ambrosia beetle associated with cacao plants in South Sulawesi, Indonesia[7]. The beetle, also known as the black twig borer, infests numerous cultivated trees and forests worldwide[8,10]. Several common fungal associates of X. compactus on cacao trees belong to the genera Fusarium, Diaporthe, Lasiodiplodia, and Ceratocyctis[7]. Some species of Lasiodiplodia and Fusarium are important pathogens of cacao plants that cause dieback and canker diseases and Fusarium vascular dieback (FVD), respectively.

The objectives of this study were to determine: (1) the occurrence, symptoms, and impact of the X. compactus on cacao seedlings in East Luwu, South Sulawesi, Indonesia; (2) the fungi associated with the decline of cacao seedlings under X. compactus infestation; (3) the pathogenic potential of the fungi associated with the decline of cacao seedlings under X. compactus infestation; and (4) the growth of fungi is associated with the decline of cacao seedlings under two common ambient temperatures (30 and 35 °C) in cacao fields in South Sulawesi.

-

Seedling samples were collected from a commercial cacao seedling nursery in Tarengge Village, Wotu District, East Luwu Regency (Indonesia). Cacao trees in this area were previously reported to be infested by X. compactus[7]. The nursery house was shaded with UV plastic as a roof and surrounded by 85% black paranet as a ½ wall. One hundred 3-month-old seedlings were randomly selected from the commercial nursery house and then transported to a greenhouse at Hasanuddin University Makassar, which was about 500 km away from the original place of the seedlings. During the transportation, the seedlings were kept free from X. compactus infestation. The seedlings were maintained in the greenhouse under the same environmental conditions as the nursery and watered as necessary. Thirty days after their arrival, the seedlings were examined to determine the percentages of infested, wilting, and dead seedlings. Wilting seedlings were processed further for fungal isolation.

Fungal isolation and identification

-

Fungal isolations were conducted from two sources: wood sections of infected beetle galleries and larvae of the X. compactus. To sample from infected beetle gallery stem sections, dark brown to black lesions at the stems were selected. The stems were longitudinally cut in half, and then the bark was removed. The wood sections were taken from symptomatic tissue until the leading edge of symptomatic tissue was less than 1–2 cm in length. The sections were then subjected to a surface sterilization process with 70% ethanol for 3 min and rinsed three times with sterilized water.

To sample from larvae of the X. compactus, white, very small, legless larvae were selected. All live larvae were transferred to a potato dextrose agar (PDA; Merck) medium supplemented with chloramphenicol as an antibiotic for fungal isolation from the stem gallery without surface sterilization. Then, both wood sections of the infected beetle gallery and larvae of the X. compactus were plated on PDA. All Petri dishes were incubated at 25–28 °C in the dark for 24 h, and fungal growth was checked daily for two weeks. Fungal mycelia were taken from the growing margin of the culture after incubation periods ranging from two days to two weeks using a cork borer and placed in new Petri dishes containing a new PDA medium under aseptic conditions for further purification and identification of the fungi. All sub-cultured fungal isolates were incubated in the dark at 25–28 °C for 24 h. Isolated fungi were identified based on their colony and morphology characteristics under a microscope. The fungal microscopic features were observed and photographed using a Nikon ECLIPSE E100 microscope.

Leaf disk bioassay

-

All isolated fungi from both wood sections of beetle galleries and larvae were examined through a leaf disk bioassay to screen their potential to be pathogenic on cacao. Light green but non-hardened cacao leaves (stage 3)[17] were gathered from a clonal cacao tree. The leaves were rinsed with tap water, rounded cut with a diameter of 27 mm, and placed on wet Whatman paper in 50 mm Petri dishes. Then, a five mm-diameter fungi agar plug was placed off-center beside the midrib of the leaf disk for inoculation. Petri dishes were incubated at 26−27 °C under 12 h light and dark cycles. Sterile PDA agar plugs were used as Controls. Lesion progression on the leaf blade (lamina) and main vein (midrib) was measured singly at 24-h intervals and recorded until one of the treated leaves was thoroughly covered by fungal mycelia. Each isolate had four replications of leaf disks (one per plate). The percentage values were subjected to the formula below to assess the area under the disease progress curve (AUDPC)[18]:

$ {\rm{AUDPC}}= {\sum }_{i=1}^{n}\left[\dfrac{(y_i+y_{i+1})}{2}\right]\left(t_{i+1}-t_i\right) $ Where yi = percent of diseased leaf area on the ith date; ti = date on which the disease was scored (ith day); n = number of dates on which disease was scored.

Preparation of seedlings, pathogenicity testing, and re-isolation

-

Seeds of the clonal trees of MCC 02 were harvested for rootstock production, MCC 02 originated from the North Luwu Regency of South Sulawesi Province, Indonesia. The clone was selected by local farmer selections that were developed by two cacao farmers, M. Nasir and H. Andi Mulyadi, in 2006. In 1987, a farmer named M. Nasir discovered a superior cocoa tree. Following this discovery, H. Andi Mulyadi employed clonal propagation techniques, specifically side grafting, to propagate the cacao tree. MCC 02 is known for its high yield and resistance to vascular streak dieback and pod rot disease[19]. Farmers in Sulawesi and Indonesia have widely planted the clone. Additionally, it has been certified and recommended by the Indonesian government for cultivation[20]. Also, the clone is comparatively tolerant to dieback disease caused by L. theobromae[21].

The selected seeds were washed, removed from their placenta, soaked overnight, and treated with 1% Dithane M-45 fungicide (i.e. mancozeb 80%). Then, the seeds were kept in the germination sack. The germinating seeds were planted in poly-ethylene (PE) bags (15 cm × 22 cm) filled with unsterilized soil. Seedlings were placed in a nursery shade house with UV plastic as a roof and maintained under sufficient irrigation conditions. The temperature inside the nursery ranged from 27 to 33 °C during the daytime, and relative humidity ranged from 76% to 90%.

The stem inoculations were performed on 6-month-old seedlings with an average stem girth of 5.8 mm. For inoculation, the surface of the stem bark was disinfected with 70 % ethanol and left to dry. A 9-mm square cut was made into the wood between two nodes. An 8-mm diameter mycelial PDA round plug was removed from the edge of actively growing cultures and placed onto the stem wounds, with the mycelium facing the cambium. The inoculated wounds were wrapped with Parafilm M (Bemis) to prevent desiccation and contamination. The Parafilm remained for the entire experiment period. Control plants were inoculated with sterile PDA agar plugs.

The air temperature was recorded daily in the greenhouse and varied between 25 to 34.5 °C, and relative humidity ranged from 88.8% to 99% during the daytime. During a week after inoculation, the temperature varied from 29.9–34.5 °C, and relative humidity ranged from 79% to 99% from 11:00 am to 04:00 pm (daytime).

Evaluation of infection and re-isolation

-

The disease development was evaluated by measuring vascular streaking length at the end of the experiment (3 months after inoculation). Dark brown to black vascular streaking length was measured with a digital calliper.

At the end of the experiment, all tested fungi were re-isolated from each experimental plant to confirm Koch's postulates. Lasiodiplodia from symptomatic inoculated stems was re-identified using morphological colony characteristics. Re-isolation was conducted from treated and untreated plants onto a PDA medium. Seedling stems were surface sterilized with NaOCl solution (5 %) for 3 min and rinsed in sterilized water three times. Approximately 3–5 mm diameter pieces of stems were placed on a PDA medium supplemented with chloramphenicol and incubated at room temperature in the dark.

Data statistical analysis

-

Data on lesion development and vascular streaking progression were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with two treatments, namely, leaf disk test, and pathogenicity test on seedlings. When significant differences were detected, means were separated by LSD's test at a 5% level of significance (p < 0.05).

-

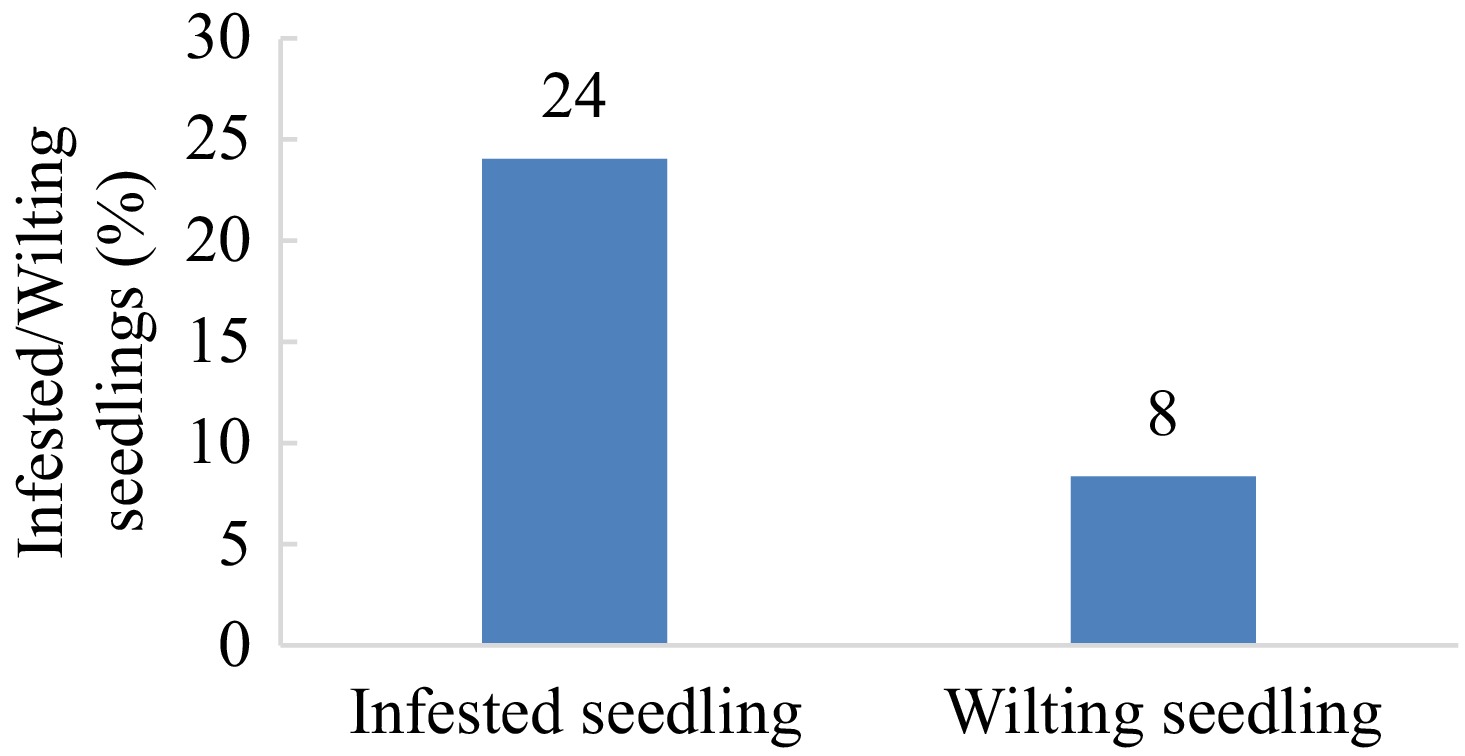

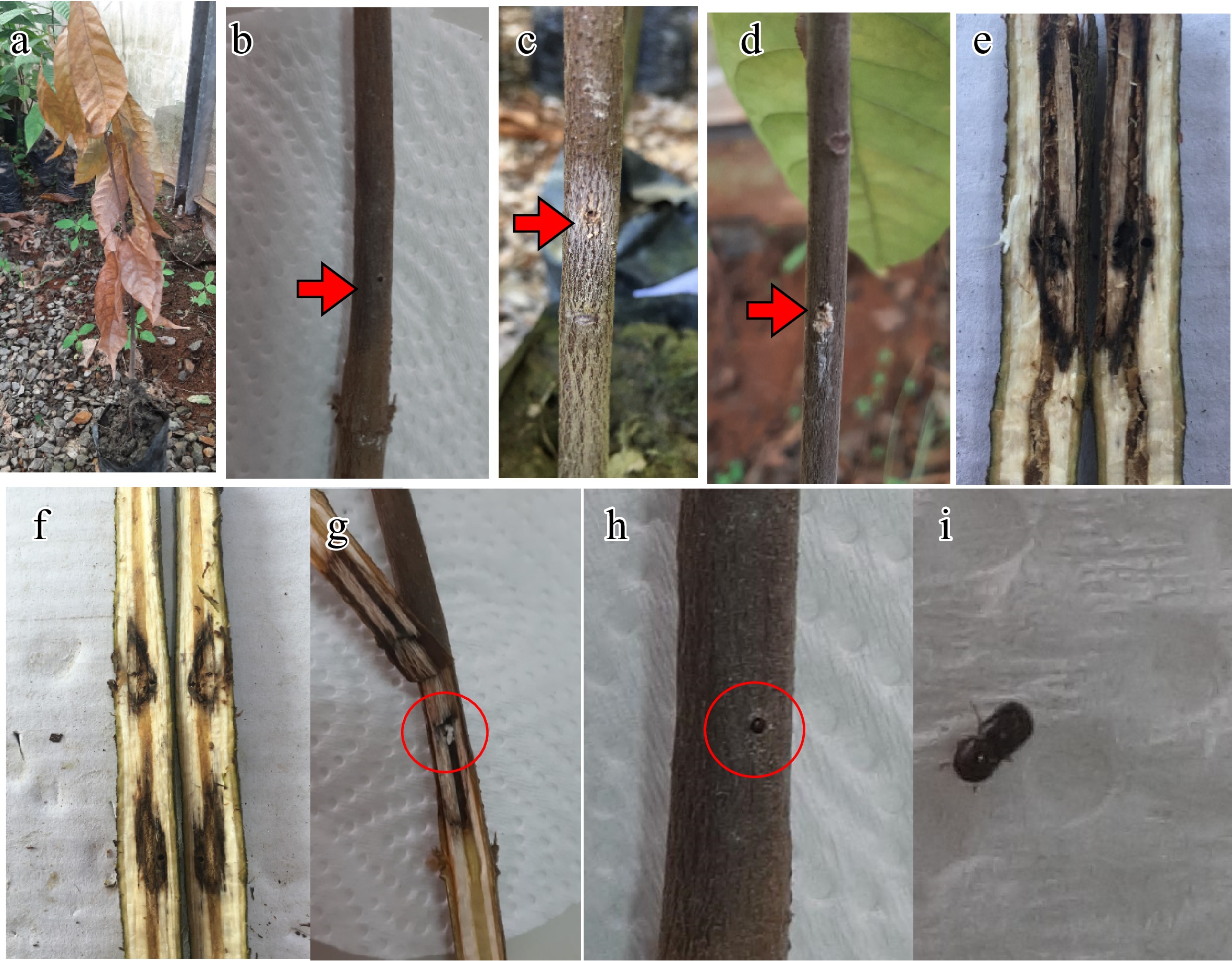

A total of 100 sample seedlings were examined for X. compactus infestation. During the evaluation (30 d after separating the seedlings from a commercial cacao seedling nursery), 24% of seedlings showed symptoms of attack by the beetle, and among the infested seedlings, 8% were wilted (Fig. 1, Fig. 2a). Infested seedlings showed distinct symptoms, including 1 mm diameter boreholes on the stem. Usually, the boreholes are surrounded by smooth frass (Fig. 2b–d). Some of the infested stems were observed to be dark brown to black necrotic on wood tissue around the boreholes, along the cambium until the bark of the stem (Fig. 2e–g). A group of larvae and a beetle were sometimes seen inside the internal gallery (Fig. 2g–i).

Figure 1.

Percentage of infested and wilting cacao seedlings under X. compactus infestation in East Luwu, South Sulawesi, Indonesia.

Figure 2.

External and internal symptoms of Xylosandrus colonisation on cacao seedlings in East Luwu, South Sulawesi, Indonesia. (a) Decline/wilting seedling. (b) Borehole with dark brown to black lesion around the hole (arrowhead). (c), (d) Borehole with powdery frass (arrowhead). (e), (f) Internal galleries with dark brown to black lesions around the inside holes. (g) Dark brown to black necrotic on wood tissue around the bore hole and internal gallery with a group of larvae inside (red circle). (h) Beetle in entry/exit hole. (i) Beetle.

Fungal isolations from wood galleries and larvae

-

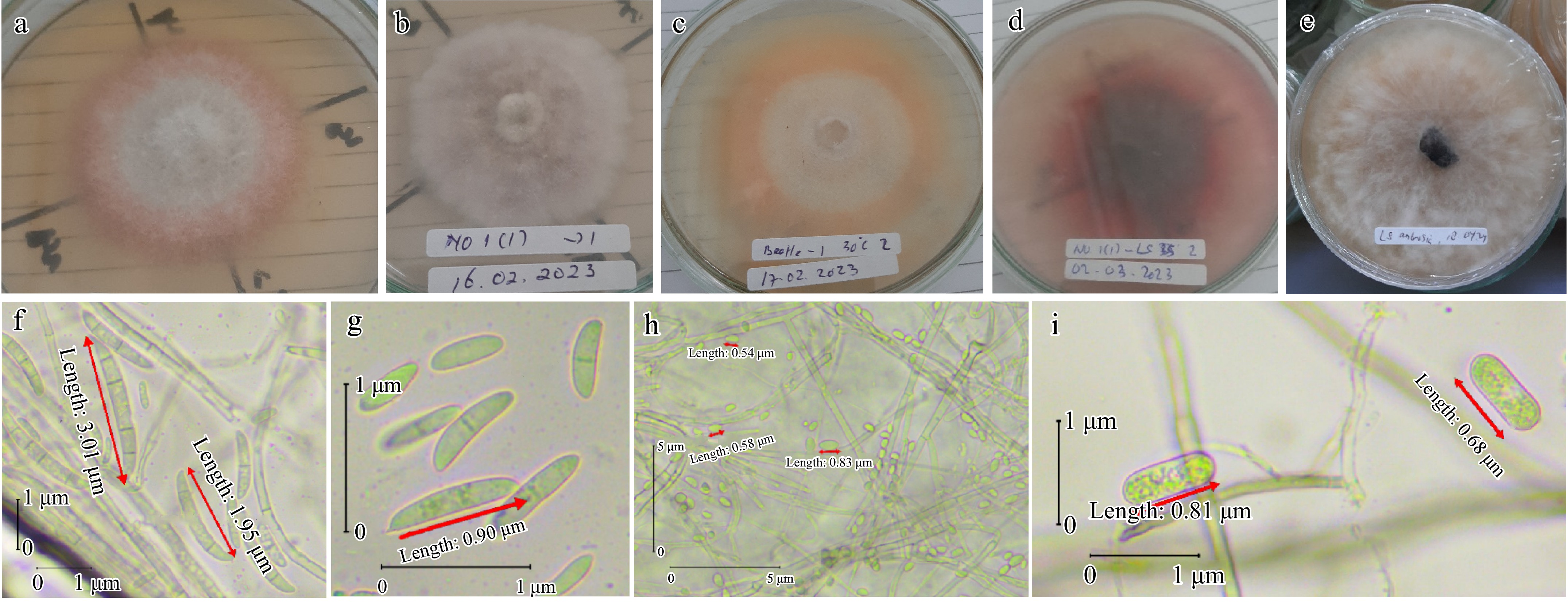

Three morphotypes resembling Fusarium Link species, Lasiodiplodia Ellis & Everh. species and Colletotrichum Corda species were recovered from symptomatic tissue of internal galleries and larvae (Table 1; Fig. 3). Two morphotypes resembling Fusarium Link species and Colletotrichum Corda species were recovered from larvae. Fusarium represents 57%, Lasiodiplodia 14%, and Colletotrichum 28% of total isolates recovered from symptomatic tissue of internal galleries and larvae, more significant than the Lasiodiplodia and Colletotrichum (Table 1). Based on culture morphology and microscopic characteristics, two, one, and one isolate were designated as Fusarium, Lasiodiplodia, and Colletotrichum, respectively, out of 14 isolates representing the fungi (Table 1; Fig. 3).

Table 1. Associated fungi with infested plant parts under X. compactus infestation and larvae of X. compactus on cacao seedlings in East Luwu, South Sulawesi, Indonesia.

Material

originFusarium sp. Lasiodiplodia sp. Colletotrichum sp. Total Wood sections of infected beetle galleries Surface sterilization 2 1 1 4 Without surface sterilization 3 1 1 5 Larvae 3 0 2 5 Total 8 2 4 14

Figure 3.

Morphological and conidia features of fungi associated with wilting seedling of cacao. (a) Fusarium sp. colony features after 10 d at 30 °C. (b) Colletotrichum sp. colony features after 12 d at 26–29 °C. (c) Fusarium sp. colony features after 12 d at 30 °C. (d) Lasiodiplodia sp. colony features after 6 d at 35 °C. (e) Lasiodiplodia sp. colony features after 6 d at 26–29 °C. (f) Microconidia (two-celled oval) and macroconidia (typical Fusarium macroconidium; apical cell; blunt; basal cell; foot-shape; four-six cell). (g) Microconidia (oval and two-celled oval) of Fusarium sp. (h) Aseptate, hyaline, subovoid, ovoid, and globose conidia of Colletotrichum sp. (i) Ellipsoid young conidia, hyaline, aseptate, and granular contents of Lasiodiplodia sp.

Leaf disk bioassay

-

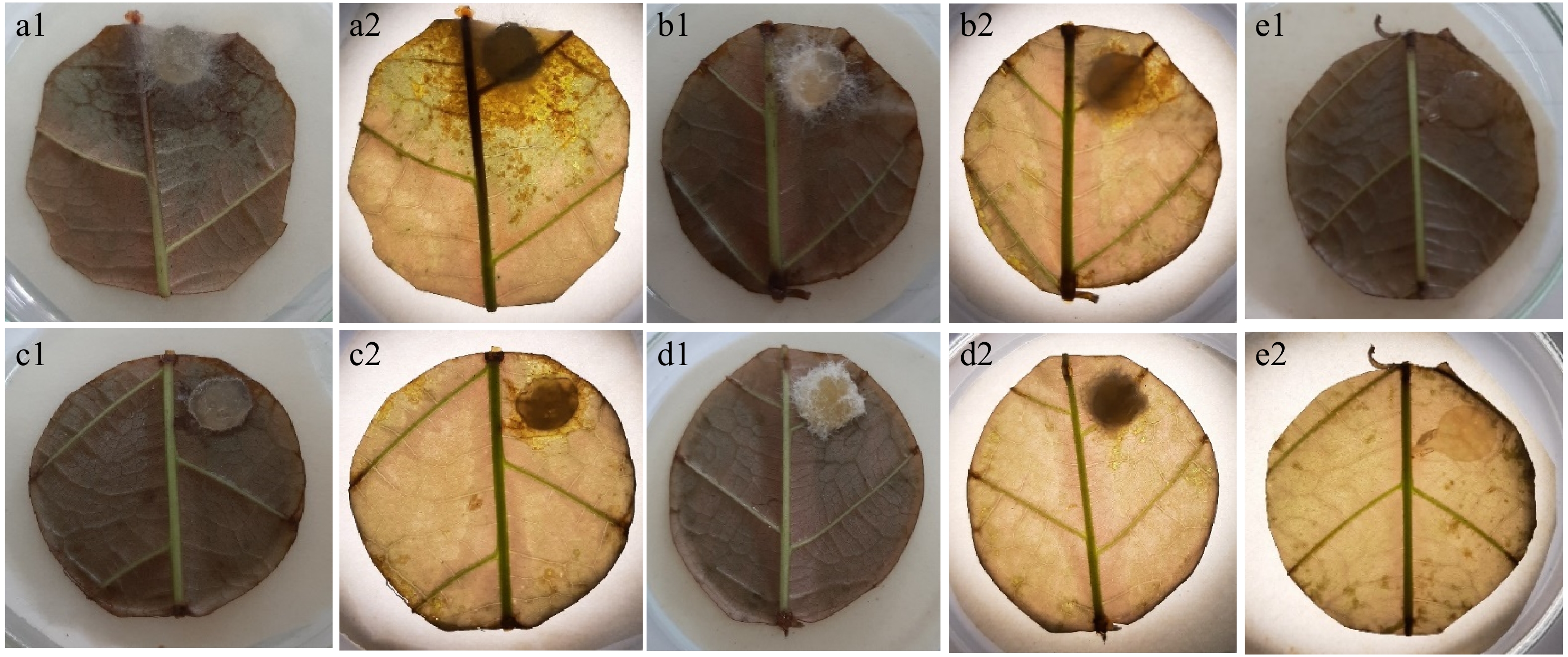

Four fungal isolates with a representative isolate for the four major taxonomic groups were tested for their aggressiveness on early-stage three cacao leaves (Table 2, Fig. 4, Fig. 5). AUDPC was determined using the area under necrosis (% of the area) (Table 2, Fig. 4, Fig. 5). The Lasiodiplodia isolate induced more necrosis than the other isolates. The lesion development area of 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h was 14.4%, 55.0%, and 81.3%, respectively, and an AUDPC value of 102.8 on the leaf blade (lamina). In addition, on the leaf main vein, the lesion development area of 24 h and 48 h was 22.5% and 67.5%, respectively, and the AUDPC value was 45.0. The aggressiveness of the Lasiodiplodia isolate was greater than that of two isolates of Fusarium and Colletotrichum isolate (Table 2, Fig. 4, Fig. 5).

Table 2. Lesion development and AUDPC values (%) of lesions 24, 48, and 72 h after inoculation on the leaf blade and 24 and 48 h after inoculation on the main vein. Leaf blade necrosis was analyzed separately from the main vein necrosis.

Fungal isolates Leaf blade Main vein 24-h 48-h 72-h AUDPC 24-h 48-h AUDPC Lasiodiplodia sp. 14.4a 55.0a 81.3a 102.8a 22.5a 67.5a 45.0a Fusarium sp. 0.8b 2.5b 8.1b 6.9b 0.0b 0.0b 0.0b Fusarium sp. 0.0b 1.8b 5.0b 4.3b 0.0b 0.0b 0.0b Colletotrichum sp. 0.0b 0.8b 4.5b 3.0b 0.0b 0.0b 0.0b Control 0.0b 0.0b 0.0b 0.0b 0.0b 0.0b 0.0b Numbers in the same column followed by the same letter are not significantly different by LSD's test analysis (p < 0.05).

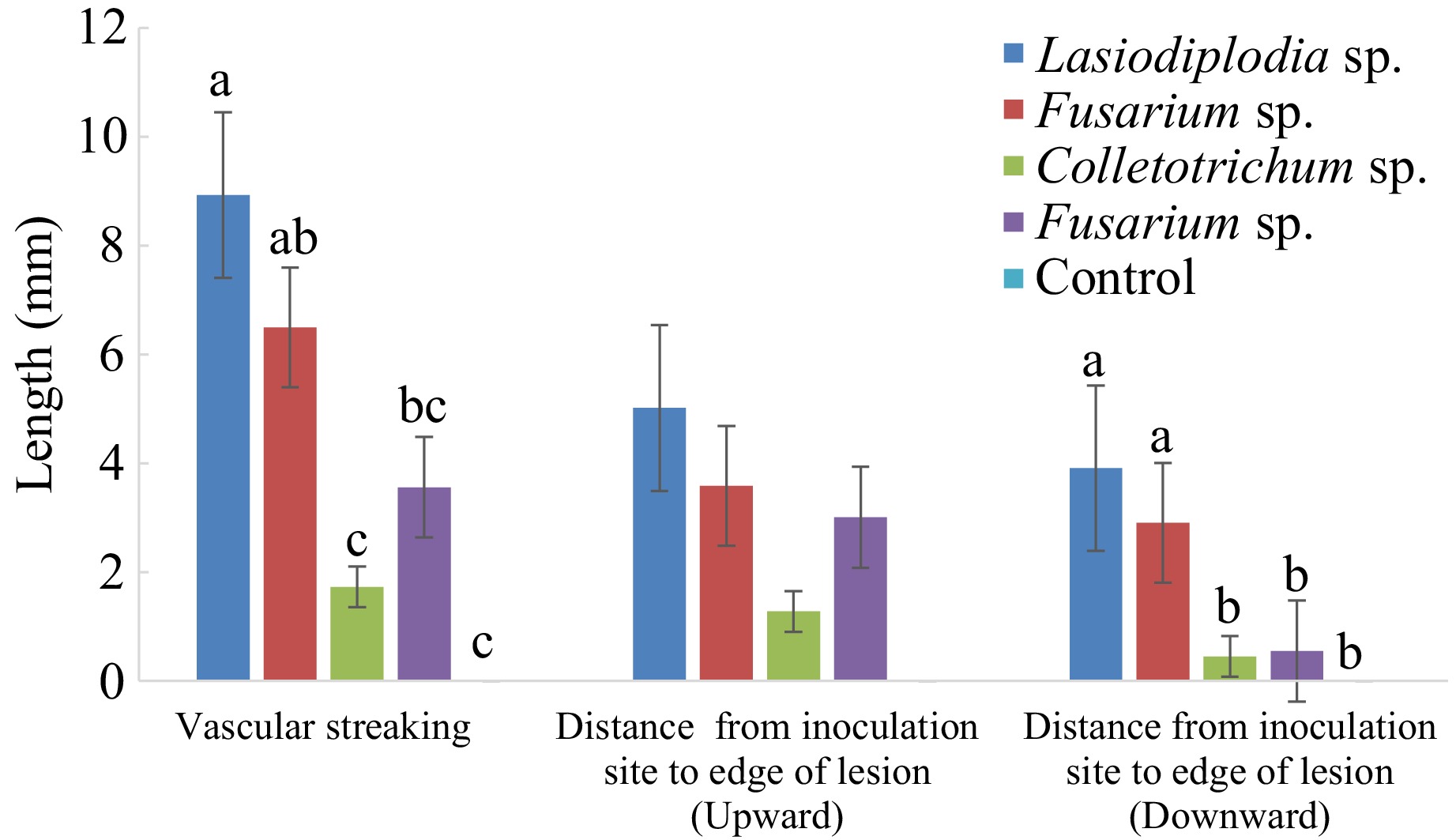

Figure 4.

Vascular streaking length (mm) in the stem of cacao seedlings inoculated with associated fungi with Xylosandrus and its infected stem with PDA as a control inoculum for 95 d. Bars with the same letter do not differ significantly according to the Least Significant Difference (LSD) test at p ≤ 0.05.

Figure 5.

Necrotic lesions on stage 3 leaf disks 48 h after inoculation in the leaf disk bioassay. (a1) Inoculation with Lasiodiplodia isolate; (a2) observed under a microscope. (b1) Inoculation with Fusarium isolate; (b2) observed under a microscope. (c1) Inoculation with Fusarium isolate; (c2) observed under a microscope. (d1) Inoculation with Colletotrichum isolate; (d2) observed under a microscope. (e1) No necrotic lesions obtained on controls treated with sterile PDA agar plugs; (e2) observed under a microscope.

Pathogenicity tests

-

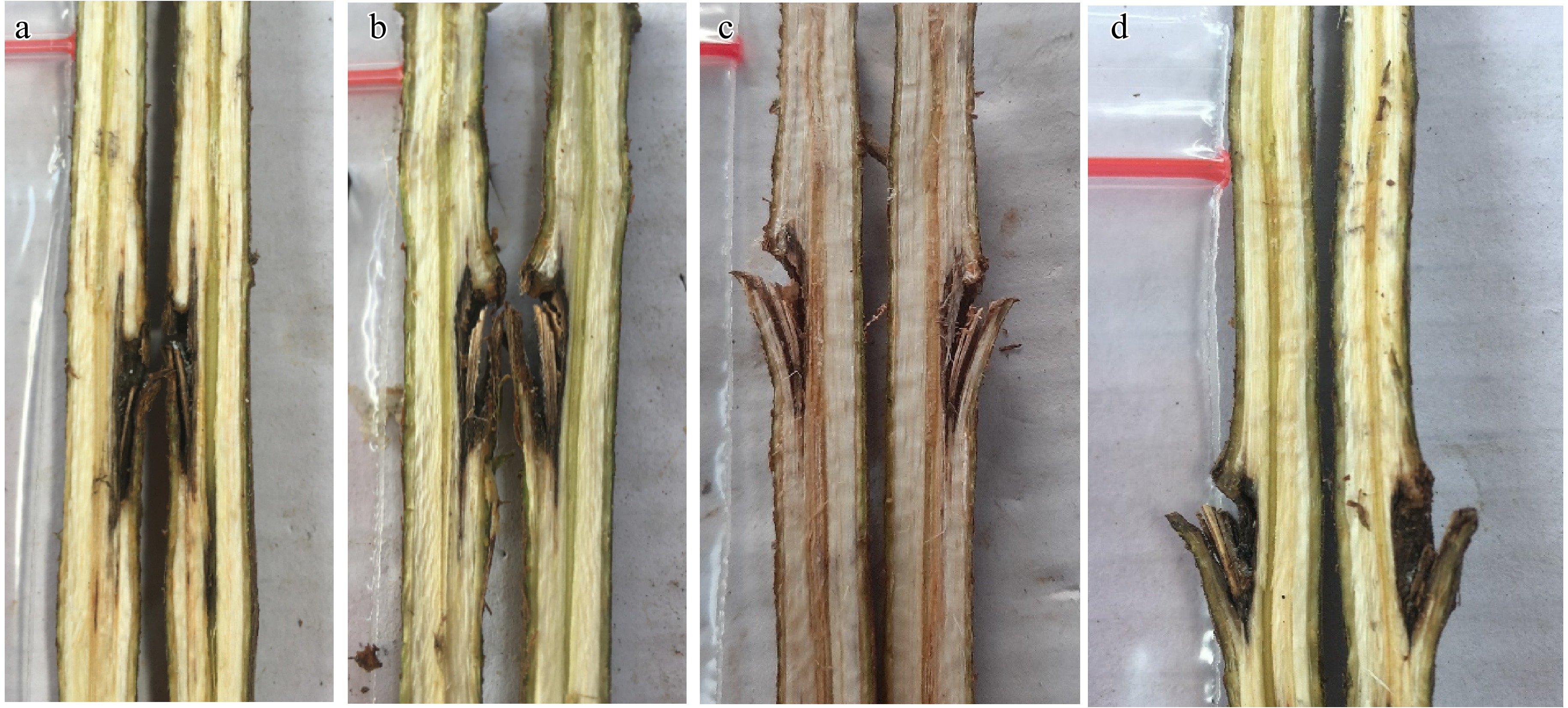

Pathogenicity tests were performed on 6-month-old rootstock seedlings inoculated with four fungal isolates. The dark brown to black vascular streaking (Fig. 6a–c) on inoculated seedlings was measured 95 d after wound inoculation. The vascular streaking length significantly differed in most fungal isolates from the control. Lasiodiplodia sp. caused a longer lesion length of 8.9 mm. However, the lesion length caused by the Lasiodiplodia sp. was not significantly different from that caused by the Fusarium sp. (isolate 1) by 6.5 mm. Meanwhile, the pathogen moved upward and downward from the inoculation site. No dark brown to black vascular streaking was observed on control-treated seedlings. Lasiodiplodia, two isolates of Fusarium, and Colletotrichum isolate were recovered from the treated seedlings but not the control seedlings.

Figure 6.

The vertical necrotic section of the fungal inoculated stem showed various sizes of dark brown to black vascular streaking 95 d after inoculation. (a) Lasiodiplodia isolate. (b) Fusarium isolate. (c) Colletotrichum isolate. (d) The vertical section of control showed symptomless/no vascular streaking.

Temperature effect on mycelium growth

-

The effect of the ambient temperature of the cacao field in South Sulawesi on radial growth and growth rates of the four fungal isolates is shown in Table 3. All fungal isolates can grow at 30 °C, but only half of all fungal isolates can grow at 35 °C. Lasiodiplodia isolate grew faster over a range of temperatures from 30–35 °C than other fungal isolates. A Lasiodiplodia isolate grew over the Petri dish surface at 30 °C within 2 d. In addition, the fungus can grow at 35 °C but a little slower than at 30 °C to grow over the Petri dish surface. Interestingly, some of the colonies of the Lasiodiplodia produce red pigment around the colony at 35 °C (Fig. 3d). No growth occurred at 30 and 35 °C within 2 d after inoculation for the Fusarium isolate (isolate 1 and 2) and Colletotrichum isolate. The colony of fungi was observed 2 d after inoculation at 30 °C. However, the colony of fungi has not reached the edge of the Petri dish within 8 d. Interestingly, no growth occurred at 35 °C for the Fusarium isolate (isolate 1) and Colletotrichum isolate, except the Fusarium isolate (isolate 2) that started to grow 2 d after inoculation. Comparing the two temperature regimes, 30 °C was optimal for all fungal isolates.

Table 3. Growth rates (mm/d) of the fungi associated with cacao decline seedlings under X. compactus infestation at 30 and 35 °C. Isolates were grown on PDA at the temperatures shown in the figures.

Fungi 30 °C 35 °C 1 d 2 d 4 d 6 d 8 d 1 d 2 d 4 d 6 d 8 d Lasiodiplodia sp. 22.0 40.0 -* -* -* 8.1 16.9 35.8 36.7 -* Fusarium sp. 0.0 0.0 12.3 17.4 21.3 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Fusarium sp. 0.0 0.0 18.5 26.4 33.1 0.0 0.0 6.6 11.3 13.3 Colletotrichum sp. 0.0 0.0 7.8 11.9 17.4 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 *The growth has reached the end of the medium. -

This study found infestation of the ambrosia beetle in cacao seedlings was quite high in a commercial nursery shade house with UV plastic as a roof in South Sulawesi. The number of wilting seedlings under this infestation is a cause for concern, as it can potentially impact the production of seedlings. The typical external symptom appears to be boreholes producing sawdust in the form of frass surrounding exit holes. A dark brown to black lesion around the inside holes and the internal gallery was observed at the declining seedling, along with a group of larvae and a beetle that was sometimes found in the internal gallery. This situation not only extends the existing threat of the ambrosia beetle (X. compactus) to cacao plantations in South Sulawesi, Indonesia[6,7] but also brings concern about the potential spread of the beetle to cacao plantations in other parts of Sulawesi, Indonesia.

Morphological characterization analyses identified four fungi associated with the decline of cacao seedlings under X. compactus invasion, namely two Fusarium isolates, Lasiodiplodia, and Colletotrichum. The emergence frequency of the four morphotypes during the isolation in this study varied with the galleries and larvae. Bioassay and pathogenicity testing demonstrated that the Lasiodiplodia isolate caused significant lesions, which are virulent on leaves and twigs of cacao. Lasiodiplodia is a well-known group of fungi to cause diseases in many hosts, including cacao[22−31]. The three other fungi, particularly Fusarium isolate 1, are considered to slightly affect healthy cacao seedlings. Also, this finding may extend the threat of Lasiodiplodia species already present in cacao plantations through a possible supplementary beetle vector (X. compactus) besides other indirect penetration methods.

During the isolation from galleries and larvae, the most abundant fungal group isolates recovered were Fusarium. Fusarium species and Colletotrichum species were both consistently isolated from galleries and larvae. This finding is not surprising because Fusarium belongs to a diverse genus recognized as the most fungal associate of the ambrosia beetle[32−34]. Fusarium associated with ambrosia beetles is assumed to significantly contribute to nutrition for beetle development[35,36]. Further analysis is needed to identify the Fusarium group. Fusarium have been isolated from diseased and healthy tissues of cacao trees[31,37−40]. However, one of the members of Fusarium has been reported as a causal agent of dieback symptoms in mature trees of cacao in Ghana and Sulawesi, Indonesia[25,38,41].

Members of Lasiodiplodia were less plentiful than Fusarium. Lasiodiplodia species were isolated only from galleries. However, their emergence from diseased seedlings under X. compactus infestation here is interesting, even though the fungal is not a typical fungal associate of the ambrosia beetle. However, several studies reported the association between Lasiodiplodia species and ambrosia beetle[42−45]. Lasiodiplodia species have been recovered from many tissues and conditions of cacao, diseased or healthy[31,37,40,46−49]. In addition, Lasiodiplodia sp. is a significant fungus on cacao, causing dieback, pod rot, canker, and root and collar rot symptoms around the world, including South Sulawesi, Indonesia, particularly the species L. theobromae and L. pseudotheobromae[25,31,46,48−51]. Lasiodiplodia species are able to colonize healthy tree tissue without rendering symptoms[52] and may act as a latent pathogen after endophytic infections[53−55].

Similar to the Fusarium species, the Colletotrichum species was consistently isolated from infected galleries and the whole body of larvae. However, only low numbers of Colletotrichum were isolated. This finding matches those observed in earlier studies that Fusarium species have identified as the most fungal associates of ambrosia beetle and as the important source of nutrition for ambrosia beetle (including Xylosandrus spp., Xyleborus spp., and Euwallacea spp.)[35,36,56]. Meanwhile, Colletotrichum species have been found to be associated with cacao trees, and some of them cause diseases[28,37,39,40,57,58].

The presence of Fusarium in high numbers is most likely the conditions of galleries and larvae supporting the recovery of Fusarium, or they were defeating other beetle fungal symbionts. However, the spatial segregation of the fungal-associated communities frequently occurs across an individual beetle[56]. In addition, in an occupied range, the fungal communities' number and variety may also be influenced by the gaining of other fungi from the surrounding environment or plant[34,59]. These segregation patterns make the distribution of fungal communities different: active transmission (carried via the mycangia), and passive transmission (unintentionally carried). All isolated fungi, however, were not isolated from the beetle mycangia, probably demonstrating a more phoretic association[15,56,60]. Isolated fungi in this study aligned with previous research on fungi associated with mature cacao trees, including Fusarium and Lasiodiplodia[7].

The bioassay and pathogenicity tests showed consistent results, with the Lasiodiplodia isolate performing more aggressively than other isolates, followed by Fusarium (isolate 1). However, none of the treated seedlings wilted and died in the pathogenicity tests. In addition, the progression of necrosis in the vascular system was considered slow. The slow progression of the disease is probably caused by the genetics of the rootstock used in the study, which is the rootstock produced by beans from comparatively tolerant clones of T. cacao MCC 02. Despite this slow progression, the Lasiodiplodia isolate was the most aggressive fungus among the fungi associated with ambrosia beetles. Aggressivity of Lasiodiplodia associated with the attack of ambrosia beetles causing plant diseases have been reported in various plants, including Mangifera indica L., Persea americana, and Tectona grandis[42−44,61,62]. Meanwhile, results of the pathogenicity test for Fusarium in this study indicate that one of the Fusarium was likely to cause cacao disease despite low infection rates. However, different results may occur for fungal aggressivity and pathogenicity tests on different cacao leaves and seedlings because the study used a cacao clone of S1 for the leaf disk test and MCC 02 for the pathogenicity tests.

The Lasiodiplodia isolate grew best and faster at two regimes of ambient temperatures of the cacao field in Sulawesi under laboratory conditions of 30 and 35 °C. This result might explain why Lasiodiplodia can grow and develop in tropical environmental conditions[63,64]. The three other fungi grew slowly at 30 °C and poorly at 35 °C, the latter of which is typical of Sulawesi ambient temperatures during the daytime.

Our results highlight the potential economic impact of associations between ambrosia beetles and fungi in cacao seedlings, where cacao seedlings are damaged by infestation of ambrosia beetles along with their fungal associates. Ambrosia beetles can accelerate the spread of plant pathogens to healthy mature cacao trees and cacao seedlings, acting as an effective and efficient mode of transport for plant pathogens[15,65−71]. Thus, it is reasonably assumed that ambrosia beetles accelerate the spread of Lasiodiplodia in East Luwu, South Sulawesi, Indonesia.

Although ambrosia beetles on cacao are relatively new in South Sulawesi[7], the beetles were confirmed to attack cacao seedlings under a nursery house, causing wilting symptoms in relatively high incidence. The results of this study demonstrate the potential threat of this ambrosia beetle as a vector of fungi that affects cacao growth and the need for a greater understanding of the ecological relationships in cacao ecosystems and the continued surveillance of the diversity and identities of their fungal associations. Further detailed insect-fungal studies are essential to understanding biosecurity and cacao health risks. Also, molecular identification of the fungi based on the nucleotide sequences would be better for working with the fungal characterization. Furthermore, this study indicates that the long-lived infested seedlings present a risk factor for furthering the long-distance spread of the beetle and fungal associates between locations. Reiterating that the use of healthy seedlings should be an essential component for managing the beetle and the disease.

-

The investigation results indicate that wilting cacao seedlings under X. compactus infestations are associated with the presence of pathogenic fungi. Fusarium, Lasiodiplodia, and Colletotrichum were isolated from the galleries of infected wood. In addition, the investigation into the aggressiveness and pathogenicity of fungal associates demonstrated that Lasiodiplodia sp. exhibited the highest level of aggressiveness among the isolated fungi and revealed the highest growth at temperatures of 30 and 35 °C. This study enhances our understanding of the association between X. compactus and the fungal pathogen, elucidating how this relationship exacerbates the susceptibility of cacao seedlings to wilting disease.

-

The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Asman A, Iwanami T; material preparation and data collection: Asman A, Rosmana A, Nasruddin A, Sjam S; analysis and interpretation of results: Asman A, Iwanami T, Rosmana A; draft manuscript preparation: Asman A; review and editing: Iwanami T, Nasruddin A, Asman A. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

-

The first author would like to thank Mr Anwar (Ayye) for assistance in providing cacao seedlings. Muhammad Agung Wardiman, S.P., Nurmala Rasyda, S.P., Mr Kamaruddin, Mr Ardan, Mr Ahmad Yani, S.P., M.Si for the technical assistance.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2025 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press, Fayetteville, GA. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Asman A, Iwanami T, Rosmana A, Nasruddin A, Sjam S. 2025. Pathogenicity of fungi associated with seedling wilting under Xylosandrus compactus infestation on Theobroma cacao in South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Beverage Plant Research 5: e027 doi: 10.48130/bpr-0025-0014

Pathogenicity of fungi associated with seedling wilting under Xylosandrus compactus infestation on Theobroma cacao in South Sulawesi, Indonesia

- Received: 25 November 2024

- Revised: 02 March 2025

- Accepted: 31 March 2025

- Published online: 19 September 2025

Abstract: Ambrosia beetles, a significant concern in maintaining cocoa productivity, are now considered an emerging pest on cacao in some areas of South Sulawesi, Indonesia. Xylosandrus compactus, the most prevalent species, has been found colonizing many cacao seedlings in a nursery. This study aimed to determine the incidence and impact of the X. compactus infestation in cacao seedlings, the pathogenic potential, and the growth of the fungal associates. From a commercial cacao nursery we randomly sampled 100 three-month-old rootstock seedlings. The beetles were identified morphologically, and then the associated fungi were isolated. The present study found that X. compactus attacked 24% of cacao rootstock seedling samples, and 8% of them showed wilting symptoms. Morphological examination identified four fungi recovered from infested galleries and larvae: two Fusarium isolates, one Lasiodiplodia isolate, and one Colletotrichum isolate. The leaf disk test showed that the Lasiodiplodia isolate was the most virulent, while the other fungal isolates were less aggressive. Pathogenicity tests were performed on rootstock seedlings of cacao, with a Lasiodiplodia isolate producing longer vascular streaking than the other fungi. Temperature tests showed that Lasiodiplodia grew well and faster under two ambient Sulawesi's prominent temperatures, 30 and 35 °C. These findings corroborate our previous study regarding X. compactus in cacao and provide insights into the potential threat of the beetle as a pest and a vector of plant pathogens in cacao seedlings. Also, these findings suggest that the use of infested seedlings can result in the spreading of the beetle.

-

Key words:

- Ambrosia beetle /

- Cacao rootstock /

- Fusarium /

- Lasiodiplodia /

- Seedlings decline /

- Wilting