-

Carotenoids are a group of colored substances commonly occurring in green and yellow leafy vegetables with their structure consisting of a 40 carbon polyene backbone[1]. Carotenoids are further classified into carotenes (β-carotene and lycopene) with the structural formula C40H56 and xanthophylls (lutein, zeaxanthin, cryptoxanthin, neoxanthin, and violaxanthin) that have oxygen in their molecular structures[2,3]. Carotenoids play a vital role in quenching reactive oxygen species and inhibiting tumor growth[2]. In addition to being a dietary source of retinoids, carotenoids are associated with several therapeutic functions. Protective effects against dangerous disorders such as degenerative eye diseases and cancer have been reported[3,4].

Carotenoids exist in many different chemical forms. Among the various dietary carotenoids, provitamin A activity is expressed by those with at least one terminal β-ionyl ring. β-carotene, α-carotene and β-cryptoxanthin show provitamin A activity while others such as lycopene, lutein, and zeaxanthin do not convert into vitamin A in the human body[2]. Vitamin A, chemically, known as retinoids are absorbed in the intestines and stored in the liver. The conversion occurs in living systems with the aid of enzymes. The two carotenoid cleavage enzymes β-Carotene ′ oxygenase-1 and β-carotene 9′,10′ oxygenase-2 occurring in humans are known to aid in bioconversion of β-carotene to retinoids[2,5]. β-carotene is the most commercialized and well-established representative of lipophilic nutraceutical owing to its function as a natural coloring material, antioxidant activity, and dietary source of vitamin A. β-carotene is naturally present in trans isomeric form in foods while other cis isomers may also occur[4,6].

The knowledge of the factors influencing the stability of naturally colored β-carotene emulsions in food systems is essential in developing their new applications. There is an increasing inclination for consumers to prefer natural colors over synthetic colorants in foods and beverages. With increasing consumer preference for natural sources, the use of colors such as carotenoids in food and beverages has increased[7−9]. However, natural alternatives are susceptible to environmental stresses encountered during processing including heat, light, pH, and oxygen. β-carotene is a bioactive substance that degrades with time, and factors such as high temperature, light exposure, and air contact expedite the degradation.

Color is an essential marker for quality; thus there is an interest in understanding the stability of natural food colorants to degradation factors[8,10]. Oxidation and isomerization causes color loss of carotenoids and nutritive value[11]. Naturally occurring β-carotene is a favored means of enhancing food color[12]. An exceptional way to apply it to food is through encapsulation[12,13].

Encapsulation encases a nutraceutical bioactive substance in a protective matrix with the aim of improving thermal endurance, solubility, chemical stability, bioavailability and flavor masking[14,15]. While bioactive substances are fortified, competent encapsulation structures are essential to preserve the active material and prevent degradation during processing[12]. Encapsulated structures are known to offer protection to the encased substance, enhance solubility in aqueous matrices, deliver to the target location and retard the rate of degradation reactions[3]. Encapsulation can be achieved by emulsification, spray drying, coacervation, freeze-drying, and extrusion. Various types of emulsions that can be utilized for encapsulation of bioactive materials include conventional emulsions, multilayered emulsions, protein-polysaccharide conjugate stabilized emulsions, Pickering emulsions and nanoemulsions[16].

Oil-in-water (o/w) emulsions are popular for improving solubility of liposoluble nutraceuticals, triggered or controlled delivery, decelerating isomerization and degradation due to its simple and cost-effective preparation method[3,17]. Emulsifiers at the oil-water interface play a pivotal role in regulating performance and functionality[3]. Natural emulsifiers are preferred by consumers due to their perceived health benefits. In a shift from well-performing conventional surfactant-based emulsifiers towards more natural Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) certified food-grade emulsifiers, proteins, and polysaccharides serve as the two main classes to work with[18,19]. Macromolecules such as proteins and polysaccharides serve as naturally derived emulsifiers. Several proteins have been proven to produce small-sized emulsion droplets due to their amphiphilic nature[3,20]. However, proteins at elevated temperatures induce emulsion destabilization due to their instability arising from pH variation, temperature fluctuation, or high ionic strength[3,21]. Long-term emulsion stability is mainly offered by stabilizers[18]. Aqueous phase polysaccharides can function as stabilizers in emulsified systems, increasing viscosity and consequently preventing droplet coalescence[22]. Polysaccharides such as modified starches largely stabilize the emulsion interface by steric repulsion thereby making the emulsified system they stabilize less likely disturbed by stresses such as heat and ionic strength[21].

This research was designed to explore the stability of multilayered emulsions made of octenyl succinic anhydride (OSA) modified starch and chitosan for enhanced stability of β-carotene in thermal treatments and during storage. Heat stability was specifically considered to expand application in thermal processing scenarios like sterilization. OSA starches are a type of modified starch and are derived from waxy maize, wheat, corn, or tapioca where the chemical modification confers unique functional properties, the most important of it being emulsification[23,24]. Chitosan is a polycationic linear heteropolysaccharide consisting of N-acetyl-2-amino-2-deoxy-ᴅ-glucopyranose and 2-amino-2-deoxy-ᴅ-glucopyranose bonded by β–(1→4) glycosidic linkages. Commercial chitosan is derived by alkaline treatment of chitin[25−30].

Studies to understand the carotenoid stability in processing and storage are essential. Many studies have explored the stability of emulsified β-carotene when subjected to heat[31,32], light[20,31,33] and in storage[3,34−36]. There has been little published information on the stability of β-carotene incorporated emulsified and bulk oil systems within transparent polymeric pouches during exposure to light. Fortified food stored in transparent pouches or PET bottles may be exposed to light during transportation in the supply chain and shelf display in grocery stores. Ensuring the stability of natural pigments in a wide variety of conditions is essential to expand their application in the food industry[12,37]. The present research attempts to systematically study the stability of β-carotene to light exposure and in storage to elucidate the extent of protection offered by encapsulated matrices against the non-encased bulk matrices. β-carotene was mixed in bulk triglyceride oils as well as dispersed in emulsified droplets of the corresponding oils. In preliminary storage tests on the degradation of β-carotene with unsaturated fats, we observed no specific trend in its degradation. Therefore, two saturated fat materials were chosen, medium chain triglyceride (MCT oil) and glycerol trioctanoate (GTO), as lipophilic carriers for β-carotene. GTO is a pure triglyceride while MCT oil contains a mixture of capric, caprylic, and lauric fatty acids according to label specifications.

-

Synthetic β-carotene, GTO, Chitosan (degree of deacetylation ≥ 75%), and citric acid were procured from Millipore Sigma Inc. (St. Louis, MO, USA). MCT oil Spring Valley water was purchased from a local store, Walmart, (Pullman, WA, USA). OSA starch was kindly supplied by Ingredion Incorporated (Bridgewater, NJ, USA). Deionized water obtained from Milli-Q Reagent Water System, (Massachusetts, USA) was utilized throughout the study. High barrier multilayer polymeric film (Structure - Coated PET//PA//PP) with an oxygen transmission rate of 1.05 cm3 m−2 day−1 and water vapor transmission rate of 5.11 gm−2 day−1 was used to prepare small size (3 in × 2.25 in) pouches.

Emulsion preparation

-

Oil-in-water emulsions with bilayer interface were constructed using two polysaccharides — OSA starch and chitosan. The multilayered emulsions were prepared by following layer-by-layer deposition of biopolymers to facilitate electrostatic interaction. First, an oil-in-water primary emulsion composed of OSA starch was prepared by a two-step homogenization process wherein an oil phase and a primary aqueous phase were homogenized using a rotor-stator homogenizer (Kinematica Polytron PT 2500E, Bohemia, NY, USA) at 7,000 rpm for 3 min. The primary course emulsions were further broken down by means of ultrasound treatment using a probe sonicator of 0.25 in diameter tip of titanium construction (Fisher Scientific Sonic Dismembrator Model 100 Hampton, NH, USA). The primary aqueous phase consisted of varying concentrations, 1.0%–2.5% w/v, of OSA starch dispersed in deionized water. Therefore, the primary emulsion had a final composition of 5% oil and varying concentrations of OSA starch as emulsifier.

Secondary emulsions were formed by slow addition of primary emulsion to the secondary aqueous phase with continuous homogenization, thus promoting the deposition of chitosan on primary emulsion droplets (Supplemental Fig. S1). The secondary aqueous phase consisted of varying proportion of Chitosan (0.025%–0.80% w/v solution) dissolved in 1% citric acid solution and was added with the primary emulsion at the ratio of 1:1. Overnight stirring was allowed for the complete hydration of biopolymers. For β-carotene loaded lipid phase, β-carotene was mixed with 10 mL MCT oil or GTO in an ultrasonic bath for uniform dissolution. Hence, secondary emulsions would have 2.5% oil, 1% OSA starch as primary emulsifier and 0.0125%–0.40% chitosan as a secondary emulsifier.

Emulsion characterization

Particle size and Zeta potential measurements

-

Particle size distribution, Zeta (ζ) potential, and Z-average size were determined using a Zetasizer Nano ZS (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). The instrument used dynamic light scattering to measure the Brownian movement of particles and correlate it to the size under the theory that smaller particles produce faster movement. In this measurement, a monochromatic light source, laser at 633 nm, is directly beamed on a suspension containing particles; the scattered light intensity is measured as a function of time. The scattered light was measured at 173° and refractive indices of 1.48 and 1.33 were specified for oil and water, respectively[38]. The emulsions were diluted 100 times before the measurements to prevent multiple scattering effect. ζ-potential reflects the charge possessed by emulsified droplets and samples were equilibrated at 25 °C before measurement.

Thermal stability

-

Emulsions were treated to a temperature of 121 °C for 60 min to simulate the maximum sterilization condition using an oil bath and a metal cell assembly as described previously[32] wherein the emulsions were filled in PET-based pouches. Prepared 10 mL emulsions were filled in PET-based pouches and sealed. The pouches were placed within an air-tight cell and immersed in an oil bath (Thermo HAAKE W15, Waltham, MA, USA) filled with Fisher's Bath oil. Once the required heating time was completed, the cells were immediately cooled in an ice bath. The particle size distribution of the treated emulsions was measured to evaluate changes in droplet size due to heat treatment.

Differential scanning calorimetry

-

To understand the state transition of prepared emulsions during heat treatments, thermograms of multilayered emulsions made up of OSA starch and chitosan interfacial materials were obtained using differential scanning calorimeter (TA Instruments, DSC Q2000 V24.11 Build 124, Newcastle, DE, USA). About 6–10 mg prepared emulsions were measured into a Tzero aluminum pan and sealed hermetically. The emulsions were subjected to temperature extremes by first freezing it to –50 °C at the ramp rate of 5 °C/min and then controlled heating at 5 °C/min up to 121 °C under nitrogen atmosphere. Another sealed pan with air served as a reference pan.

Light treatment, packaging, and storage

-

Continuous light exposure was achieved using two 7 watts 12-inch LED under cabinet lights of color temp 5,000 K placed ~18 cm above the sample with the flat surface of pouch facing light. The level of light exposure of samples within the incubator was measured as 3,530 ± 200 Lux using Dr. Meter Digital Illuminance Light meter (Model LX 1330B, range 0.1–200,000 Lux). The temperature of samples was maintained at 37 °C using an incubator (Heratherm IGS60 ThermoScientific, Langenselbold, Germany). The samples that were treated in the dark were placed in the incubator covered in aluminum foil (Supplemental Fig. S2).

Estimation of β-carotene

-

β-carotene was estimated by solvent extraction method[39] with slight modification. Briefly, a mixture of chloroform and methanol in the ratio 2:1 (v/v) was used as the extraction medium. Two hundred μL of emulsion or oil was withdrawn and 1.5 mL of organic solvent mixture was added, vortexed thrice, and centrifuged at 210 g for 5 min. The clear extract was carefully withdrawn, and absorbance was measured at 450 nm against a solvent blank. A standard curve was prepared with known quantities of β-carotene dissolved in the organic phase and used to estimate concentration from absorbance (R2 = 0.997).

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substance (TBARS)

-

Thiobarbituric acid reactive substance assay was used to estimate products of oxidation[40]. Preparation of TBA-BHT Reagent was made as follows: 2% v/v solution of Butylated Hydroxy Toluene (BHT) was prepared in ethanol—BHT solution, 75 g of trichloroacetic acid (TCA), 1.875 g of 2-thiobarbituric acid (TBA), 8.8 mL of 12 M HCL and 414.5 mL of Millipore water was dissolved together to form the TBA solution. TBA-BHT reagent was prepared by slowly mixing 500 mL of TBA solution and 15 mL of BHT solution. The reagent was stored in the dark until use. Preparation of Malondialdehyde (MDA) included the following steps: MDA standard curve was constructed using 1,1,3,3-Tetraethoxypropane (TEP). TEP dissolves in water and produces MDA. For the preparation of calibration standards, 1 μM of MDA stock solution was prepared by dissolving 25 μL TEP in 100 mL of 1% v/v H2SO4. Two mL of this stock solution was made up to 50 mL 1% v/v H2SO4 to yield 40 nM standard solution and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Standard solution was further diluted to 5, 10, 15, and 20 nM using 1% v/v H2SO4. These solutions of known concentration underwent the same procedure as the sample and absorbance was measured at 532 nm. A straight line with R2 = 0.999 was obtained as standard curve. A blank with 1% v/v H2SO4 was used for spectrophotometer (UV160U, Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). 1.6 mL of the sample was vortexed for 30 s with 3.2 mL of TBA-BHT solution, followed by heating in a boiling water bath for 15 min. The mixture was cooled to room temperature and centrifuged (Ohaus Frontier Centrifuge FC5706, Parsippany NJ, USA) at 4,430 g for 10 min. The supernatant was carefully transferred into a transparent disposable cuvette to record its absorbance at 532 nm.

Instrumental color

-

Sample color in reflectance mode with specular component excluded was recorded as L* (lightness) values ranging from 0–100, a* greenness (–) to redness (+) and b* blueness (–) to yellowness (+) respectively using a Spectrophotometer CM-5, Konica Minolta, New Jersey in CIELAB color space. The range for a* and b* are approximately 80 in positive and negative axis[41]. 2 mL samples were transferred to a clear petri dish of dimensions 35 mm diameter and 10 mm height. A measurement aperture of 8 mm

$\varnothing $ $ \Delta E=\sqrt{{{{\left({L}^{*}-{L}_{0}^{*}\right)}^{2}+\left({a}^{*}-{a}_{0}^{*}\right)}^{2}+\left({b}^{*}-{b}_{0}^{*}\right)}^{2}} $ (1) where, L*, a*, and b* are for sample stored at 37 °C for various time and L0*, a0*, and b0* are values at day 0[42].

Degradation kinetics

-

Kinetic change in quality attribute C is expressed by Eqn (2)[42].

$ \dfrac{\mathrm{d}C}{\mathrm{d}t}={-k\left[C\right]}^{\mathrm{n}} $ (2) where, [C] denotes the concentration of substrate at a given time t, k is the rate constant of the degradation reaction, 'n' stands for order of reaction.

Integrating Eqn (2) with an initial substrate concentration of [C0] for zeroth (Eqn 3), first (Eqn 4), and second (Eqn 5) order we get the following:

$ \left[C\right]=\left[{C}_{0}\right]-kt $ (3) $\mathrm{l}\mathrm{n}\left[C\right]=\mathrm{l}\mathrm{n}\left[{C}_{0}\right]-kt,\quad\quad \left[C\right]={\left[{C}_{0}\right]e}^{-kt} $ (4) $ \dfrac{1}{\left[C\right]}=\dfrac{1}{\left[{C}_{0}\right]}-kt,\quad\quad\left[C\right]=\dfrac{\left[{C}_{0}\right]}{1+kt\left[{C}_{0}\right]} $ (5) Statistics

-

Analysis of the means and standard deviations was performed in Microsoft Excel (Office 365, Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). Analysis of variance test (ANOVA) was performed using 'agricolae' package in R-Studio version 1.4.1717 following which, Tukey's HSD procedure was used to identify the means that differed significantly. The interaction effects between the independent variables carrier oil type (MCT and GTO), light/dark storage, and storage days were included in the model. The independent variables assessed include β-carotene concentration, color values (L*, a*, b*), and TBARS.

-

In this section, stable multilayered emulsions were identified and selected based on particle characteristics including Z-average size and ζ-potential as well changes due to heat treatment.

Characteristics of the primary emulsion

-

The Z-average size of OSA-starch primary emulsions was ~250 nm for all the concentrations studied. There was no significant difference in Z-average size or ζ-potential of emulsions (Table 1) stabilized by OSA starch concentrations of 1.0%, 1.3%, 1.7%, 2.0%, or 2.5% (p > 0.05). A range of biopolymer concentrations were attempted to ascertain that the interface was not short of complete coverage due to lack of emulsifier. There was sufficient biopolymer to coat the surface at 1% concentration itself. The constant ζ-potential value ~ −30 mV within the range of 1.0%–2.5% w/v OSA-starch adds to evidence that biopolymer coverage around native oil droplets is sufficient at 1% OSA-starch concentration. The value of ζ-potential is considered favorable as higher repulsive forces exist between droplets, thus preventing them from coming closer and coalescing.

Table 1. Z-average size and ζ-potential of primary emulsions prepared with varying concentrations of OSA starch (n ≥ 3).

OSA-starch concentration

(% w/v)Z-average size

(nm)ζ-potential

(mV)1.0 255 ± 28.3a −30.5 ± 1.3A 1.3 249 ± 8.2a −30.0 ± 2.9A 1.7 244 ± 1.5a −30.6 ± 2.4A 2.0 258 ± 0.6a −31.6 ± 2.1A 2.5 244 ± 1.4a −30.2 ± 1.9A Note: Means with same superscript are not significantly (p > 0.05) different. The ζ-potential obtained in the present study is in agreement with observations made by Paulo et al.[43], where ζ-potential for modified starch concentrations of 1.4% and 3.6% was recorded. It was hypothesized that a lower biopolymer concentration would be detrimental to emulsion stability upon excessive heating, and hence decided to go with the higher end of the concentration spectrum. A higher concentration was chosen with the premise that the unabsorbed polysaccharide would offer additional stability during heat treatment by the mechanism of steric stabilization. The adsorption of surface-active agent depends on its diffusion coefficient from bulk to the interface which in turn depends on the molecular weight of the emulsifier molecule. Modified starch falls on the higher end of molecular weight that stabilizes the interface (against proteins and surfactants) with a molecular weight of MW

$\cong $ In some cases, emulsion stabilization can benefit from excess polysaccharides present in the aqueous phase. This is due to emulsion acting like a stabilizer of the aqueous phase by viscosity modification and thus preventing droplets from coming closer and coalescing into larger droplets[22]. In other cases, care must be taken to prevent excess polysaccharides as it may be detrimental to emulsion physical stability by promoting bridging flocculation[44]. Hence, it is essential to establish the amount of emulsifier that is necessary to fully coat the oil droplet surface area for multilayer emulsions.

Formation and characteristics of secondary emulsion

-

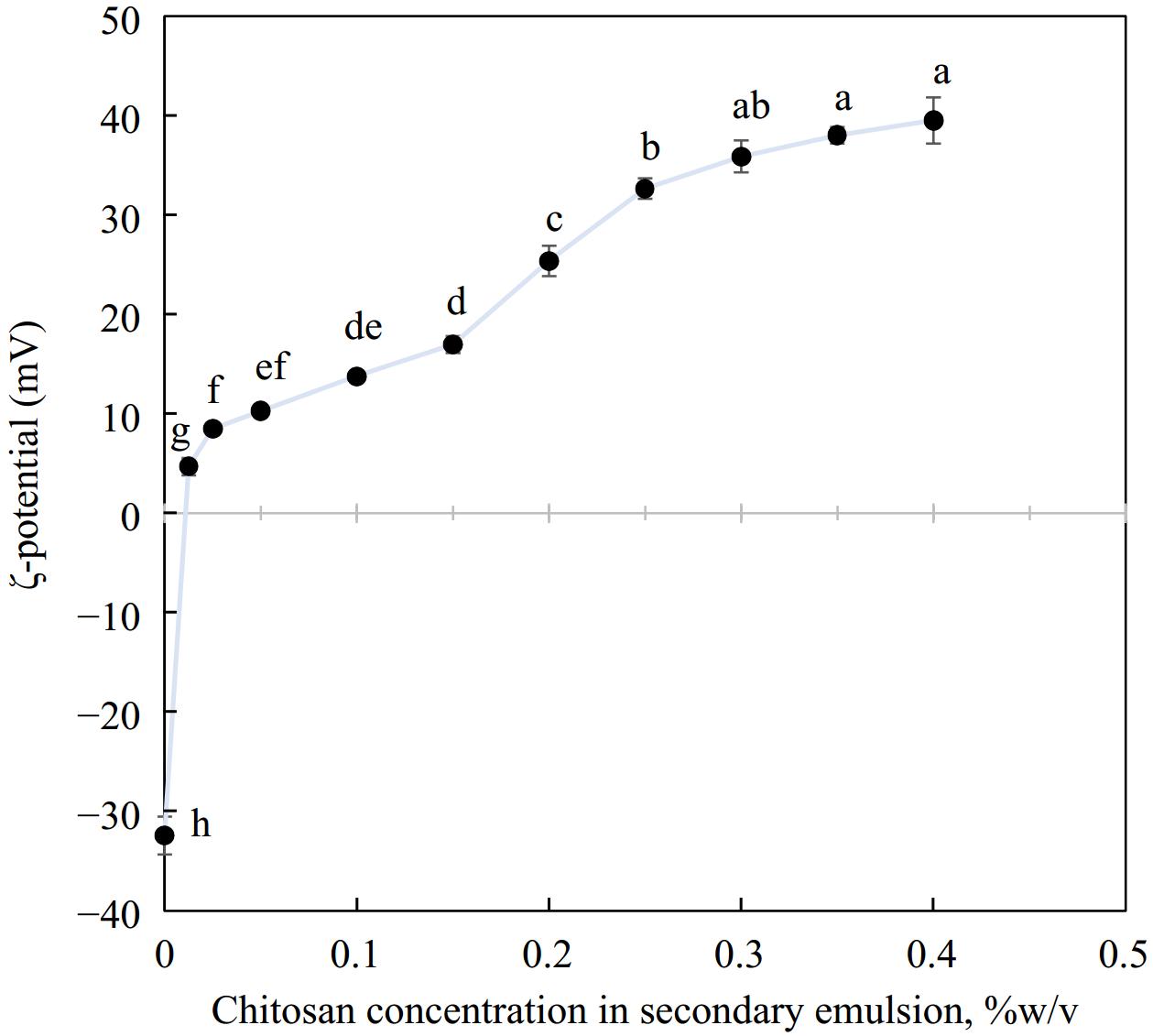

The ζ-potential of emulsions exhibited a characteristic charge reversal with the layer-by-layer deposition of chitosan over primary droplets emulsified with OSA starch. The overall charge on primary OSA starch emulsions went from highly negative (−32.4 ± 1.9 mV) to highly positive charge (+38.0 ± 0.8 mV). This can be attributed to the electrostatic adsorption of cationic chitosan on anionic OSA starch-stabilized oil droplets. Such charge reversal on the droplet surface has been reported by several researchers[17,45,46] where layer-by-layer deposition of protein or polysaccharide was utilized. From Fig. 1, it can be observed that the magnitude of the positive charge increased with increasing concentration of chitosan. It is likely that with added chitosan (0–0.3% chitosan), the previously anionic droplet surface was gradually covered with chitosan and became progressively cationic. Eventually, the surface charge evened out around 0.3% w/v chitosan. Here the droplet surface was saturated with chitosan and any further addition would not alter the ζ-potential substantially. The large positive charge recorded by emulsions around 0.3% w/v chitosan could contribute considerably to droplet stability as the electrostatic repulsion between the oil particles would keep them apart and prevent them from coming closer and coalescing.

Figure 1.

Charge reversal when secondary biopolymer chitosan was deposited over a primary emulsion interface, n = 3. Different letters represent significant difference at p < 0.05.

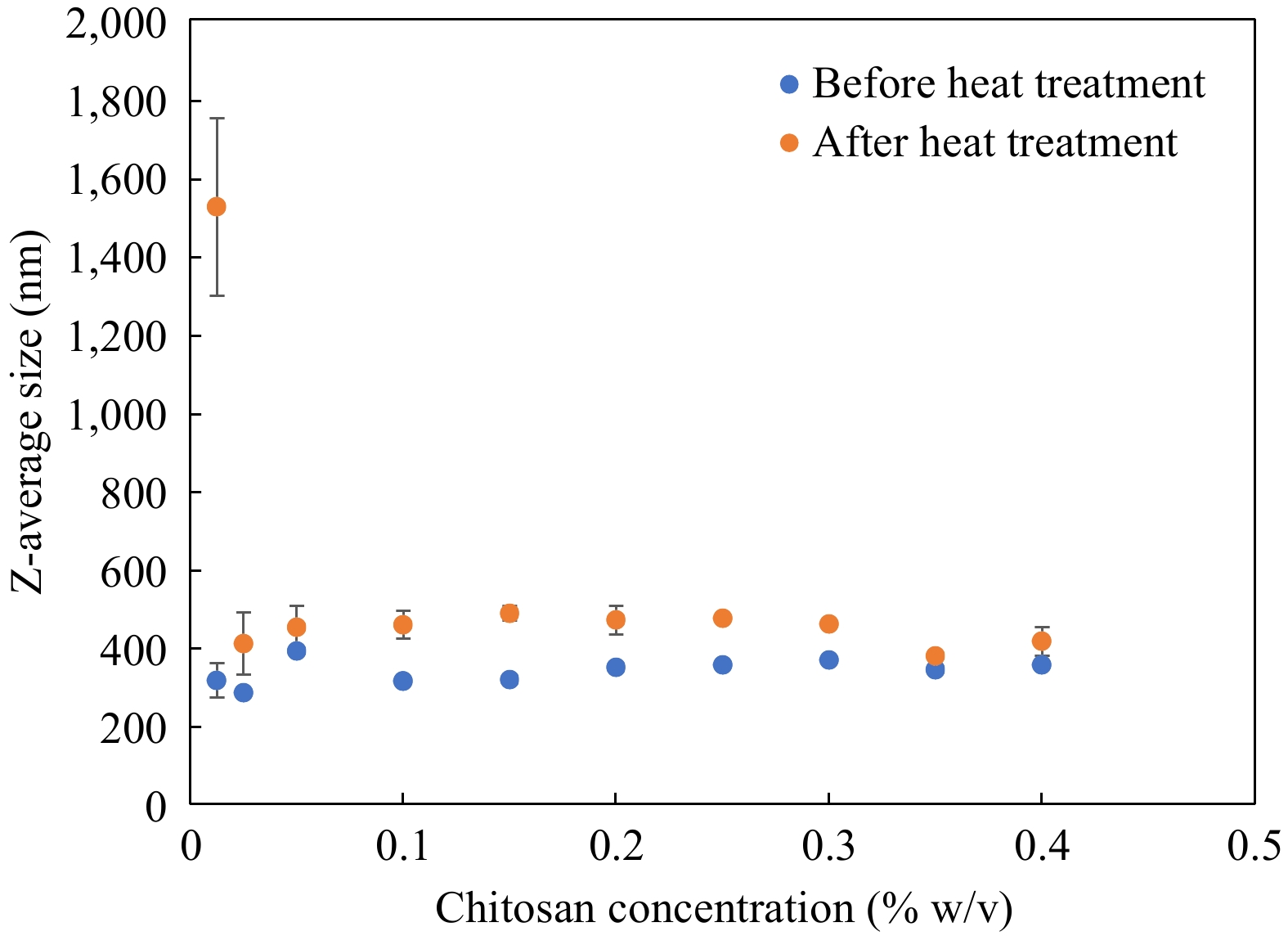

Using OSA-starch emulsions with a net negative charge of −31.6 ± 2.1 mV and Z-average size of 257.8 ± 0.6 nm as a primary base, the bilayer interface was prepared by layer-by-layer electrostatic deposition of oppositely charged chitosan. The size of secondary OSA-starch–chitosan emulsions prepared with varying proportions of chitosan ranging from 0.0125%–0.4% w/v is plotted in Fig. 2 along with the size values obtained for those emulsions when treated to heat at 121 °C for 60 min. Secondary emulsions with varying concentrations of chitosan showed similar sizes in the range of 290.4–388.5 nm for all chitosan concentrations studied. When these emulsions were treated at 121 °C for 60 min, emulsions prepared with lower chitosan recorded large increases in size. From Fig. 2, the size of emulsions formulated with 0.0125% chitosan increased sharply, from 314 ± 6.3 nm to 1,521 ± 226 nm when subjected to heat, indicating emulsion destabilization by flocculation or agglomeration. In all the other concentrations of chitosan studied between 0.025% and 0.4% w/v chitosan, secondary emulsions exhibited a stable behavior with a small increase in size. Stability after heat treatment was additionally reflected by the lack of visible emulsion destabilization phenomena such as oiling off or coagulation. Except the lowest chitosan concentration studied (0.0125%), OSA-starch–Chitosan secondary emulsions were in a consistent range of 377 ± 2.9 nm to 472 ± 8.9 nm after treatment at 121 °C for 60 min. Therefore, Z-average size measurements recorded a slight increase before and after treatment at 121 °C for 60 min, which is an acceptable change given that they underwent extreme thermal treatment. OSA starch-chitosan emulsions exhibit exceptional physical stability which could be attributed partly to the steric stabilization function of secondary emulsifiers.

Figure 2.

Change in Z-average size of emulsions before and after heat treatment at 121 °C for 60 min, n = 3. Error bars represent standard deviation.

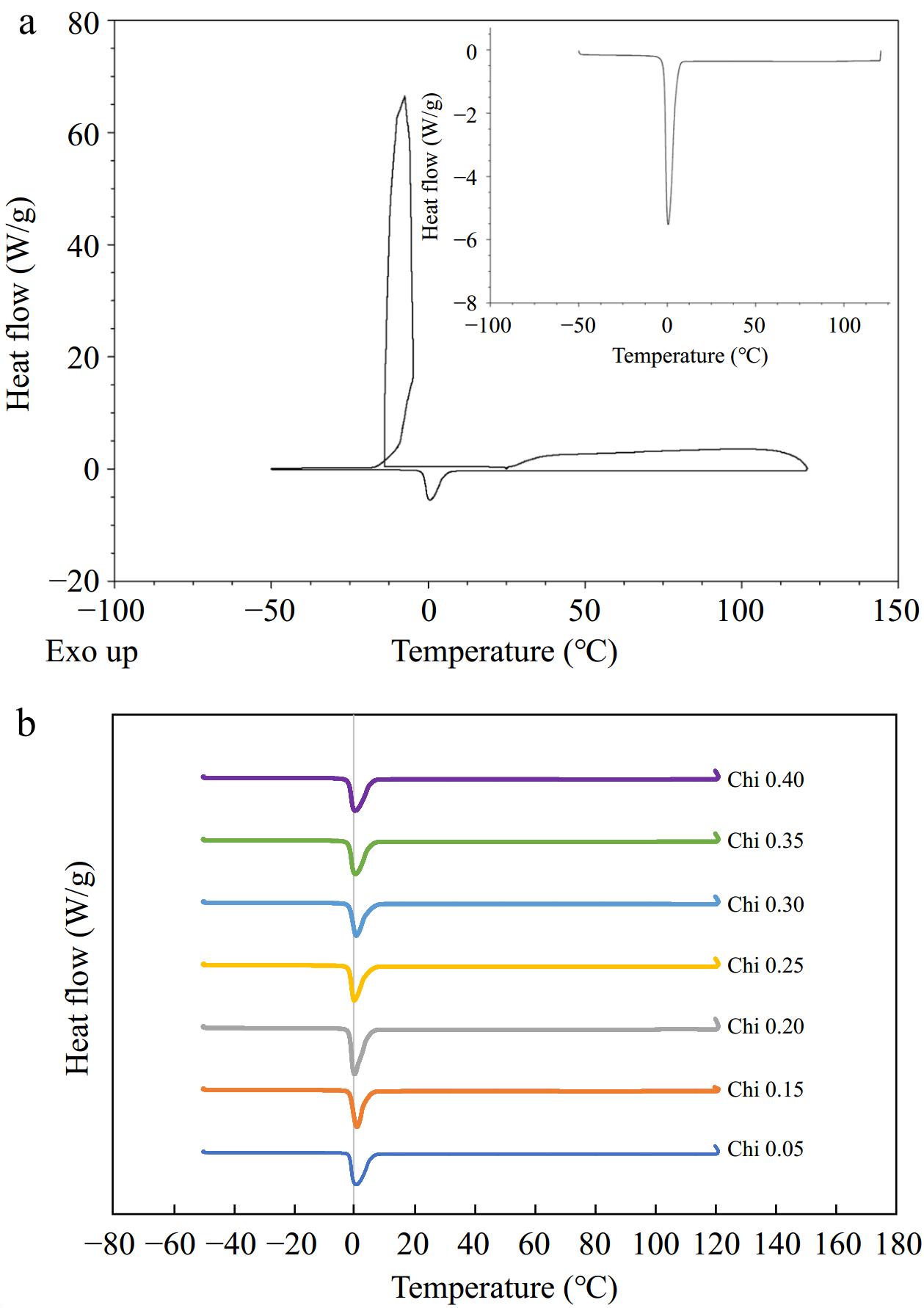

A DSC thermogram of emulsion subjected to temperature extremes is given in Fig. 3. The emulsion samples indicate an endothermic peak at about –10 °C on freezing from 25 to –50 °C, indicating freezing, and an exothermic peak on heating around 0 °C, indicating melting of emulsions. There are no degradation peaks observed during the rest of the heat ramp-up to 121 °C, indicating that the emulsions were stable to the heat treatment. Consistent thermograms were obtained for other multilayered emulsions with varying chitosan concentration (0.05%–0.4%) studied (Fig. 3b). A DSC study on hydrogels produced comparable patterns in crystallization and freezing[47] and can be considered characteristic of dispersions.

Figure 3.

(a) DSC thermogram of emulsions (0.35% final chitosan concentration) showing characteristic peak for crystallization and melting of water. Inset represents part of the thermogram that was heated from –50 to 121 °C. (b) Stacked thermograms subjected to temperature extremes, ~ –50 to 121 °C, for comparison of varying concentration of emulsifier.

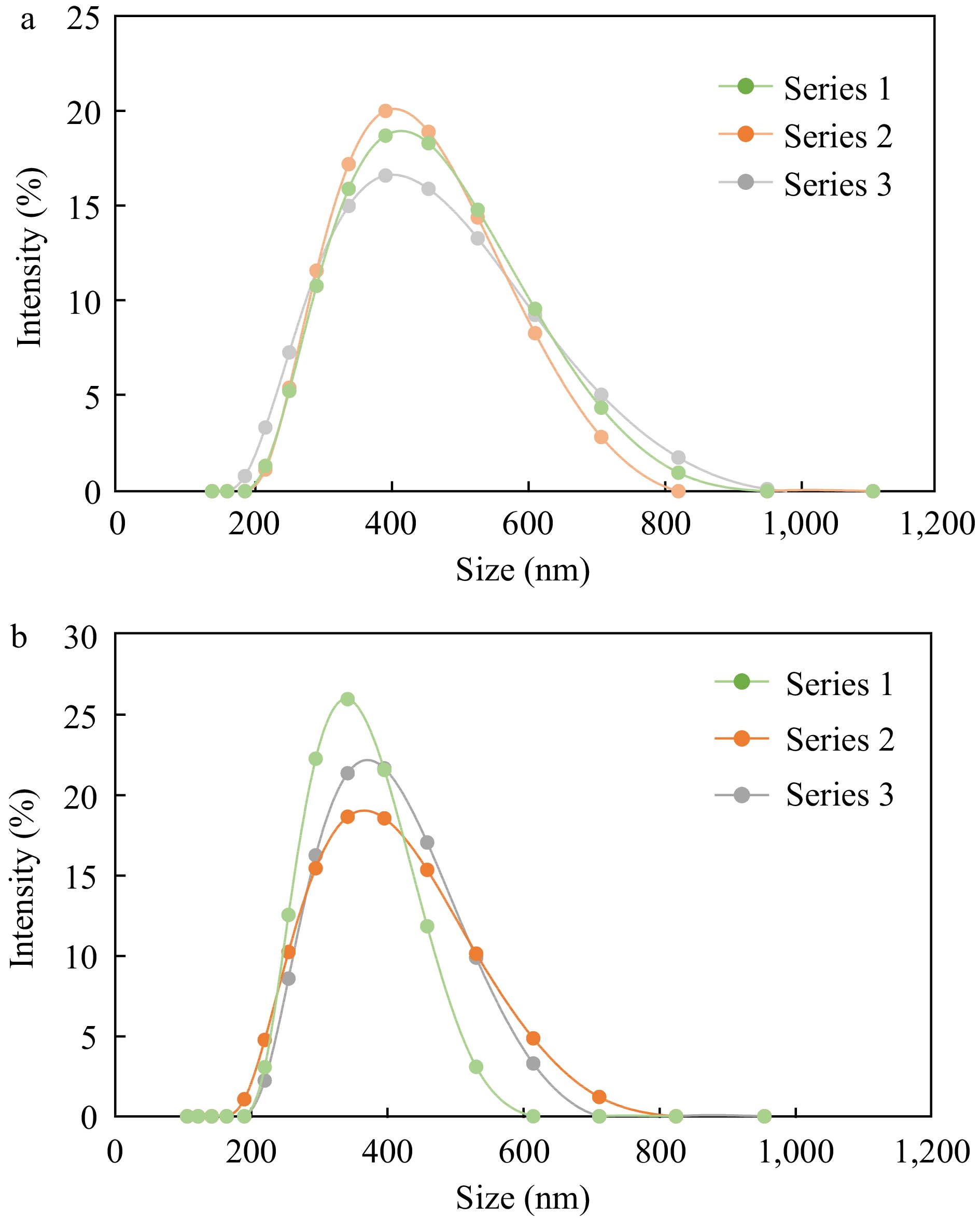

Emulsions at 0.35% chitosan concentration were selected for further study as they formed droplets with large positive charge, monodisperse particle size distribution (Fig. 4) and negligible change upon heating indicating stable dispersions. Additionally, a higher concentration of interfacial material was found to be more effective at preventing β-carotene from degradation due to the formation of thicker interfaces around emulsified oil droplets[37].

Figure 4.

Particle size distribution of (a) untreated and (b) heat treated emulsions prepared with the same concentration of chitosan (0.35%). Each chart displays distribution of three replicates (Series 1, 2 and 3).

β-carotene stability

Photostability during storage

-

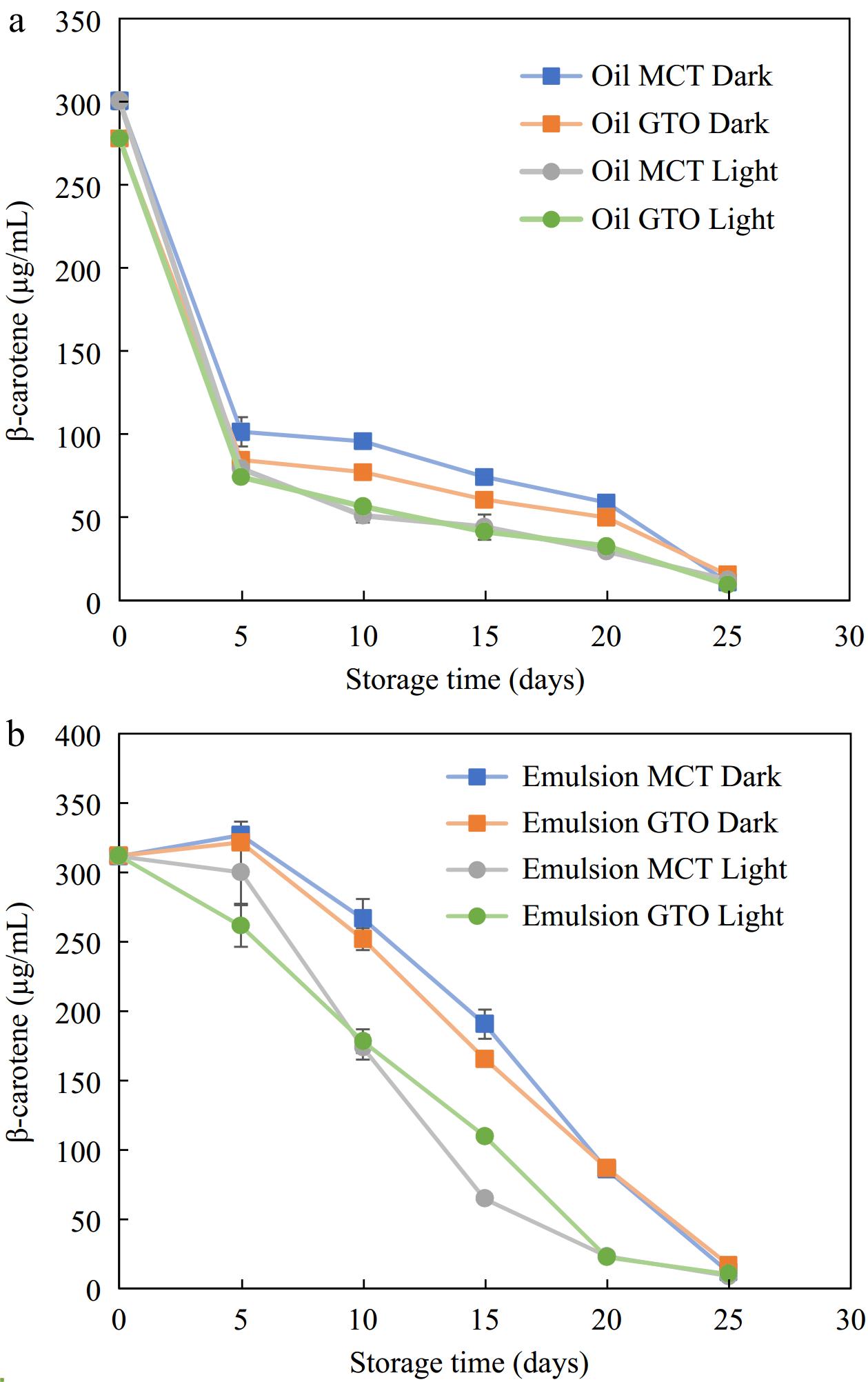

This study aimed at understanding the rate of β-carotene degradation with and without light exposure at accelerated storage of 37 °C that could be translated as the shelf life of food material. The effect of light exposure on the destruction of β-carotene is illustrated in Fig. 5a for β-carotene dissolved in bulk oil and Fig. 5b β-carotene dispersed in emulsified form enclosed within polymeric pouches over 25 d after which β-carotene degraded in all the systems studied. β-carotene in bulk oil and emulsified form were parallelly stored under dark and light storage conditions to establish its storage stability on exposure to light.

In the case of bulk oil, both dark and bright storage conditions produced slightly different results. Up to 5 d, β-carotene degradation was similar for both dark and light storage conditions. After the initial period, storage in the dark recorded lower degradation than storage in the light. For instance, on day 15, the amount of β-carotene in bulk MCT oil was 44 μg/mL (14.7% retention) when stored in light while in the absence of light, a higher amount of 74 μg/mL (24.7% retention) of β-carotene was recorded. It was noted that up to day 20, the bulk oil stored in the dark had slightly better β-carotene retention than that exposed to light. The results are consistent with the results of Liang et al.[21] who stored β-carotene dissolved in bulk MCT oil under light and dark storage at 25 °C. Their results indicate that β-carotene under dark degraded completely in 10 d and under light in 7 d. In a pure state, β-carotene undergoes auto-oxidation in the presence of light and oxygen as it interacts with free radicals such as peroxyl radicals[2].

For β-carotene in oils, a significant 3-way interaction was observed between carrier oil type, light /dark storage, and storage days (F = 9.77; p < 0.05). Significant 2-way interaction was observed between carrier oil type and storage days (F = 21.6; p < 0.05), light/dark storage and storage days (F = 55.6; p < 0.05) and carrier oil type and light/dark storage (F = 36.4; p < 0.05). Each factor effect cannot be interpreted as interaction effects are significant. For a* of emulsions, a significant 3-way interaction was observed between carrier oil type, light/dark storage and storage days (F = 42.8; p < 0.05). Significant 2-way interaction was observed between carrier oil type and storage days (F = 172; p < 0.05), light/dark storage, and storage days (F = 792; p < 0.05) and carrier oil type and light/dark storage (F = 104; p < 0.05). For b* of emulsions, significant 3-way interaction was observed between carrier oil type, light /dark storage, and storage days (F = 103; p < 0.05). Significant 2-way interaction was observed between carrier oil type, and storage days (F = 76.2; p < 0.05) and light/dark storage and storage days (F = 4,660; p < 0.05). No significant 2-way interaction was evaluated between carrier oil type, and light/dark storage (F = 0.04; p > 0.05) (Supplemental Table S1).

It can be seen from Fig. 5 that the degradation of β-carotene occurred over a span of about 25 d under dark and lit storage at 37 °C. β-carotene loaded canola oil emulsions made from OSA-starches emulsifiers showed nearly complete degradation in 13 d at 55 °C storage[35]. Similarly, in the present study, β-carotene completely disappeared in 25 d whether stored in the dark or under light conditions. To extend the retention of β-carotene for a longer period in an emulsified system, multiple antioxidants may need to be used to produce a synergistic effect. For instance, Yi et al.[3] has shown the survivability of β-carotene for 30 d in 50 °C with the aid of emulsions made from whey protein isolate-dextran-resveratrol. Resveratrol is a polyphenol compound with a myriad of biological functions including antioxidant, anti-ageing, anti-obesity anti-viral, anti-inflammatory and antitumor activity[3,48]. The presence of additional antioxidant resveratrol at the interface, besides β-carotene could scavenge and chelate pro-oxidants that extended the period of retention of β-carotene within the oil phase[3]. In addition, proteins such as WPI could have additional antioxidant effect owing to their amino acid residues that have the potential to scavenge reactive oxygen species and chelate metal ions[49]. Therefore, the amount of protection offered by the interfacial layer to β-carotene stability is pronouncedly dependent on the antioxidant nature of emulsifiers.

For β-carotene of emulsions, a significant 3-way interaction was observed between carrier oil type, light /dark storage and storage days (F = 18.2; p < 0.05). Significant 2-way interaction was observed between carrier oil type and storage days (F = 7.83; p < 0.05), light/dark storage and storage days (F = 97; p < 0.05) and carrier oil type and light/dark storage (F = 8.20; p < 0.05).

Figure 5 indicates that for the first 5 d of storage, the presence of light did not affect β-carotene retention. After 5 d, the experiments indicated that among emulsified systems studied, those stored in lighted condition degraded faster as compared to dark storage (Fig. 5b). Irradiation of β-carotene loaded emulsions with UV light were found to remarkably diminish its concentration. Guo et al.[20] observed an 82% loss of β-carotene in emulsions crafted with High Methoxyl Pectin-Rhamnolipid-Pea Protein Isolate-Curcumin complex on exposure to UV light for only 5 h. Interestingly, β-carotene loaded emulsions synthesized with OSA-modified starches recorded no significant difference between those kept under light and dark storage conditions at 25 °C[21].

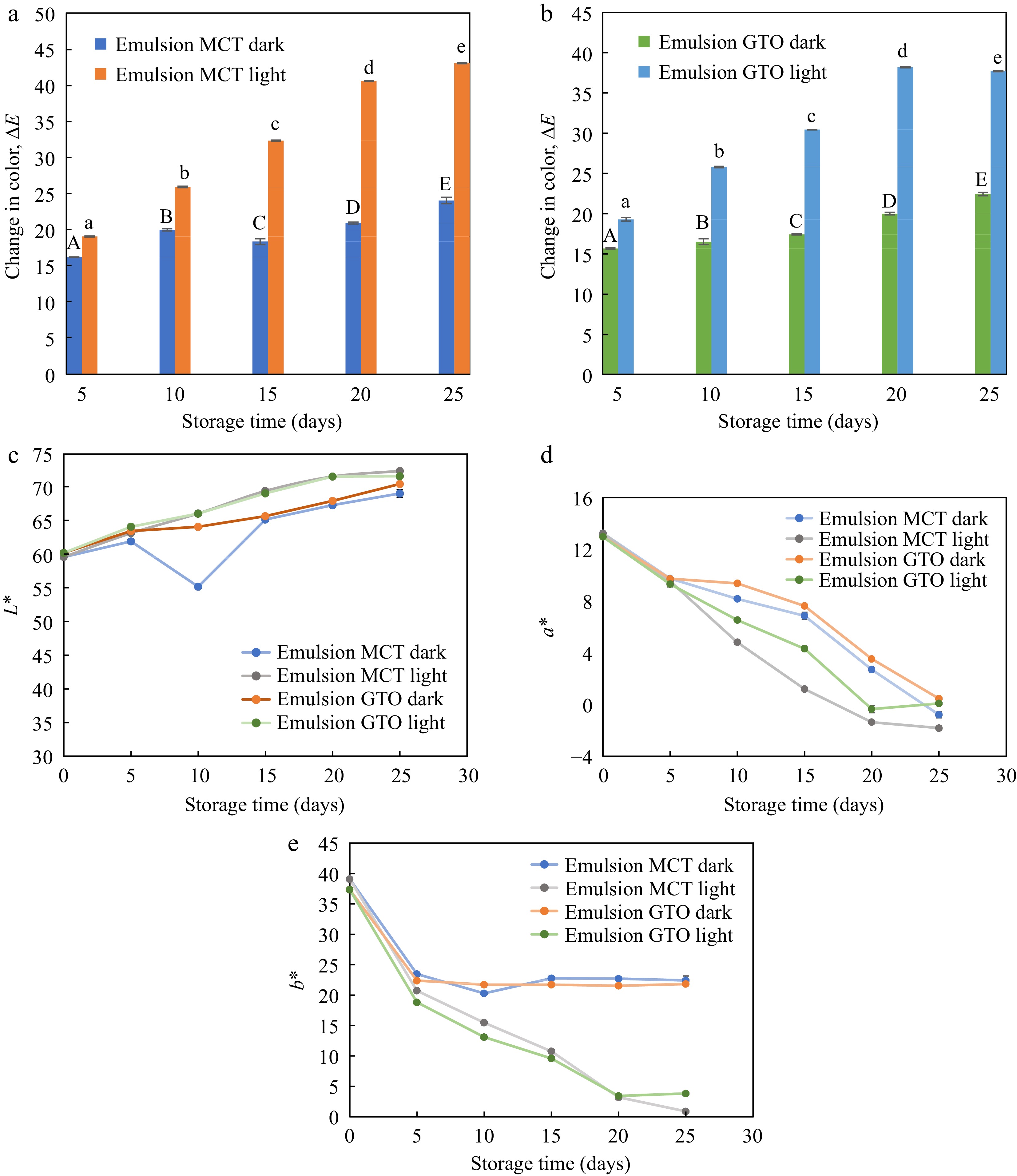

The change in color of emulsions stored at 37 °C for 25 d in the presence and absence of light with respect to freshly prepared emulsions on day 0 is illustrated in Fig. 6. β-carotene degradation resulted from isomerization and oxidation leading to loss of pigmentation. Degradation of β-carotene is not only detrimental to the biological activity of the nutraceutical but also to perceived color[3]. Therefore, the amount of remaining in emulsions were determined colorimetrically. Both emulsion carrier oils, MCT and GTO produced similar color changes (Fig. 6a & b). The chain length of fatty acids in commercial MCT oil and analytical GTO is very similar. This may explain the similarity in the trends of both carriers. The presence or absence of light had a remarkable effect on ΔE of emulsions. During 25-d storage period, ΔE spaned over a small range of 16.2–24.0 for MCT emulsion and 15.7–22.4 for GTO emulsion in the dark. On the other hand, ΔE ranged from 19.1–43.1 for MCT emulsions and 19.3–37.7 for GTO emulsions. Exposure to light increased the lightness of emulsions and reduced the yellowness much faster than when stored in the dark and showed a greater degree of ΔE variation. Color change in oils was an assortment of fluctuating measurements and therefore was not considered for making reliable assessments. A perceptible color change is known to happen when ΔE is in the range of 3.5–5 and ΔE between 1–2 can be visualized by an experienced observer[50]. All the emulsions have shown ΔE that can be visualized.

Figure 6.

Change in color of emulsions with (a) MCT carrier oil, and (b) GTO carrier oil subjected to storage under dark and light condition. Components (c) L*, (d) a*, and (e) b* of CIELAB color coordinates during storage at 37 °C, n = 3.

The CIELAB color components measured for emulsions stored under dark and light conditions are illustrated in Fig. 6c, d & e. For emulsions stored at 37 °C lightness L* increased slightly while a* and b* associated with β-carotene pigmentation dropped substantially. The drop in a* was gradual throughout the storage period while the drop in yellowness of emulsions was more prominent during the first 5 d of storage. Yellowness disappeared at different rates for emulsions stored in the dark and those exposed to light. After the initial drop in b* (to day 5) emulsions stored in the dark, essentially showed no difference until the last day of study. On the other hand, the yellowness of emulsions exposed to light continued to deplete up to day 25. A similar change in yellowness was observed by Sweedman et al.[35] where a rapid drop in the first 24 h of storage was recorded, followed by an almost constant trend for a storage period of 8 d at 55 °C. It is worthwhile to note that the emulsions synthesized by Sweedman et al.[35] has OSA starch as an interfacial material as in the present study. Therefore, exposure to light has a pronounced effect on the yellowness of β-carotene emulsions.

For L* of emulsions, significant 3-way interaction was observed between carrier oil type, light/dark storage, and storage days (F = 455; p < 0.05). Significant 2-way interaction was observed between carrier oil type and storage days (F = 454; p < 0.05), light/dark storage, and storage days (F = 908; p < 0.05) and carrier oil type and light/dark storage (F = 1,127; p < 0.05).

In summary, for short-term storage, the presence of light did not affect β-carotene stability contained within transparent polymeric pouches — both for bulk oil and emulsified systems. However, for prolonged storage, it is advisable to store β-carotene-containing systems in the dark or in light-blocking packaging material.

Effect of carrier oil

-

The two lipids used, namely MCT and GTO, exhibited similar behavior under light and dark storage at 37 °C. MCT oil mainly consists of medium-chain triglycerides and is made of saturated fatty acids. GTO also has saturated fatty acids and is a pure substance consisting of C8:0. Our previous study utilized vegetable oil made up of a variety of unsaturated fatty acids and residual antioxidants such as α-tocopherol. The sunflower oil-in-water emulsions of chitosan self-aggregates during storage at 37 °C in the dark showed an almost constant level of β-carotene during the 13-d storage period[31]. The choice of lipid carrier in the present study was made such that we eliminate the interference from such antioxidants that may be present in vegetable oil carriers so that β-carotene is the sole antioxidant in the emulsion during storage. By using a pure saturated lipid, it is expected that the main mechanism of degradation is by β-carotene alone[51].

As previously observed, the β-carotene loaded emulsions and bulk oils made from GTO and MCT carrier oils degraded in 25 d with the bulk oils exhibiting faster disappearance than emulsions. Similar behavior in MCT bulk oil incorporated with β-carotene was observed, where there was no detectable pigment after 14 d when stored at 20 °C[51]. In the case of β-carotene loaded emulsions, the degradation reported is dependent on the nature of the lipid carrier used. For instance, when vegetable oils such as corn oil or canola oil are used as carrier oil for β-carotene loading, a longer storage stability (> 30 d) of bioactive is reported[3,52]. A study comparing corn and MCT oils with sodium caseinate as interface stabilizing material found that at a storage of 25 °C, 75% of β-carotene was lost in MCT oil emulsions while only 22% β-carotene loss was reported for corn oil emulsions. Given the fact that storage conditions and emulsion interfacial composition were the same, the oil nature was the main factor that could have produced such a prominent difference. Vegetable oils may contain traces of antioxidants such as carotenoids and α-tocopherol. Though the amounts of such residual traces of α-tocopherol may be small compared to the fortification levels, it can still have a pronounced effect on the stability of carotenoids[36].

The present study utilized carrier lipids in a liquid state. However, when solid lipids were used as a carrier medium, the rate of β-carotene was higher in the case of triglycerides such as tripalmitate and tristearate and lower in the case of monoglycerides. It is possible that co-crystallization of β-carotene and monoglycerides was favored while this combination was utilized. However, when solid triglycerides were used, the accelerated degradation suggested that β-carotene was not incorporated into the crystal structure of tristearete or tripalmitate[50]. The exclusion of β-carotene from the solidified lipid fraction was also recorded by Pan et al.[53] and hence liquid lipid carriers served as better carriers during β-carotene encapsulation. Therefore, the use of solid lipids for β-carotene loaded encapsulated system should be considered with caution and take precedence over the emulsified system only if β-carotene gets incorporated into the crystal lattice. Further research is needed to carefully study the incorporation of β-carotene within solid lipid carriers.

Effect of encapsulants

-

The effect of multilayered encapsulation structure around β-carotene loaded oil phase against β-carotene dispersed in bulk oil (encapsulation absent) within polymeric pouches during storage at 37 °C in dark and lighted conditions is illustrated in Fig. 5. β-carotene in bulk oil and emulsified form are experimented simultaneously to determine the level of protection encapsulation would offer β-carotene against oxidation. Emulsions offered protection against β-carotene degradation under storage. In our studies, the samples were stored at 37 °C to reflect accelerated storage. After 5 d of storage in the dark, β-carotene in GTO and MCT bulk oils showed rapid degradation recording a loss of 70% and 66%, respectively. When protected within bilayer emulsions under similar conditions of storage and time, β-carotene loss was negligible. Extending the assessment period up to 15 d of storage, the encapsulants offer significantly better protection to β-carotene against bulk oils. This protection wears off after 20 d of storage at 37 °C.

The above results are in agreement with Li et al.[33] & Liang et al.[21]. Liang et al.[21] used OSA-modified starches of various molecular weights to prepare emulsion and compared it against bulk MCT oil. The carrier oil for emulsion synthesis was MCT and so was the bulk control, both loaded with β-carotene. Their results indicated that β-carotene dispersed in bulk MCT oil stored at 25 °C degraded completely in 7–10 d. The β-carotene loaded emulsions survived better with a retention of 51%–64%. Similar observations were made by Yi et al.[37] & Li et al.[33] where emulsions stabilized by WPI and chitosan hydrochloride/carboxymethyl starch complex offered significantly enhanced preservation than their respective bulk vegetable oils. A high internal phase emulsion of WPI nanoparticles was found to offer better protection to the internal oil phase consisting of β-carotene in corn oil against bulk corn oil control. Additional antioxidant effect from the protein WPI, which has the potential to scavenge free radicals and chelate metal pro-oxidants is also a possible reason for the enhanced stability of the emulsified system[37].

Therefore, the emulsion interface with tight packing of multilayered OSA starch and chitosan layers could have shielded from degrading free radicals and slowed the diffusion of pro-oxidants towards the core of bioactive β-carotene. The barrier effect of emulsified structure enhanced the retention of β-carotene during storage when compared to bulk oils despite both the system packaged within polymeric pouches with sufficient barrier properties of its own.

β-carotene loaded MCT and GTO bulk oils within polymeric pouches degraded more on exposure to light (Fig. 5a). Within 5 d of light exposure at 37 °C, a 74% loss in β-carotene was measured for bulk oils. On the other hand, β-carotene within emulsified oils under the same storage condition for 5 d measured significantly higher values. Furthermore, the β-carotene retention is higher in emulsions than their respective bulk oils up to 15 d at 37 °C after which, both the curves–bulk oils and emulsions, began to merge. Comparing the degradation of β-carotene due to radiation exposure from similar experiments from literature, emulsions were found to retain the bioactive over longer periods than bulk oils. For instance, a significantly higher retention of β-carotene was observed in genipin cross-linked chitosan emulsions in an 8 h UV exposure study assessing retention of β-carotene in bulk and emulsified dodecane[31]. Similarly, encapsulated β-carotene was retained better in a 7 h UV exposure study evaluating the preservation of β-carotene in bulk and emulsified corn oil systems[33]. Therefore, the present results are consistent with similar studies.

Another interesting observation revolving around the storage stability of β-carotene dispersed in MCT bulk oil was made by Liang et al.[21]. They assessed β-carotene retention with and without nitrogen flushing at 4 °C and observed that the presence of nitrogen gas within glass vials significantly slowed down β-carotene degradation in bulk MCT oil. On the other hand, nitrogen flushing in β-carotene emulsions produced no such improvements. It is possible that shielding from oxygen was achieved by encapsulated structures, and therefore nitrogen flushing made no difference in emulsions. β-carotene in bulk MCT oil was offered lesser exposure to oxygen when nitrogen was flushed. Therefore, encapsulated structures could provide a protective effect against degradation factors such as oxygen and free radicals.

There have been reports of different kinds of isomerization and degradation reactions when β-carotene in a food environment is subjected to heat, light, and storage[11]. Several pathways for isomerization and degradation of β-carotene are possible in experimental scenarios, including auto-oxidation, photo-oxidation, and thermal degradation. Over 20 oxidation products were observed for β-carotene's reaction to oxygen gas by auto-oxidation. β-carotene auto-oxidation was observed to be decelerated by the presence of radical scavengers such as BHT and α-tocopherol and accelerated by the presence of a free radical reaction initiator. These observations indicate that free radicals are involved in β-carotene auto-oxidation[54]. β-carotene under conditions of elevated temperatures undergo isomerization followed by degradation. Trans-cis isomerization of β-carotene diminishes its biological activity with cis isomers diminishing the bioavailability as vitamin A precursor, as well as antioxidant properties[55].

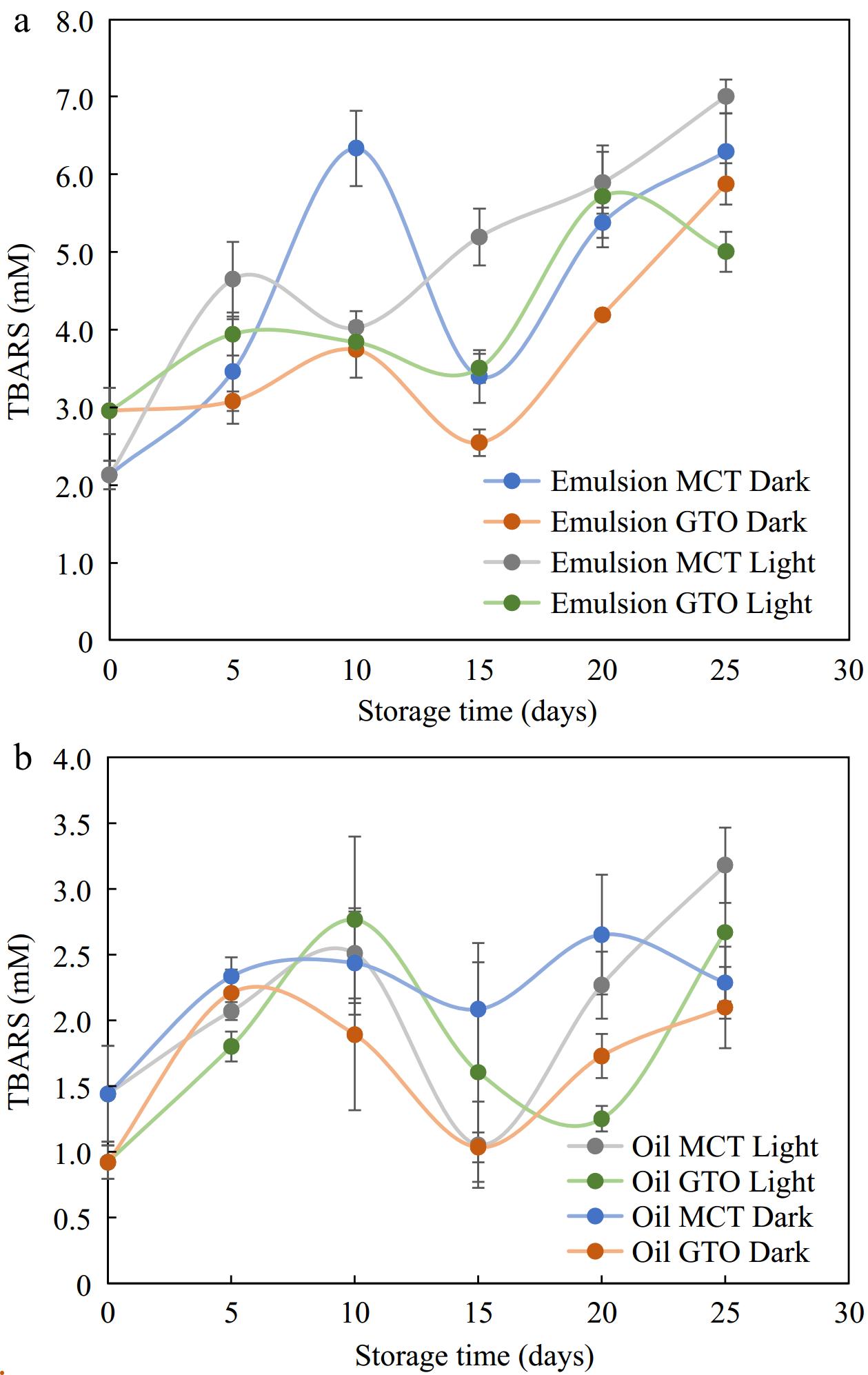

The range of TBARS obtained for 25 d for GTO oil-in-water emulsions and MCT oil-in-water emulsions stored under dark and light conditions and bulk oils stored under similar conditions at 37 °C are shown in Fig. 7. Comparing the emulsions and oils, we notice that the range of TBARS in the studied period was higher for emulsions (2–7 mM) than for oils (1–3 mM). Sharif et al.[34] produced a similar TBARS chart to the present study with regard to TBARS between emulsions and oils. The range of TBARS obtained for emulsions was higher (up to 3.5 mM) than for bulk oil of flax seed oil (up to 0.8 mM) where the secondary products of oxidation were recorded for 4 weeks. Tan et al.[56] reported that lipid oxidation could proceed faster in emulsions as compared to bulk oil. Emulsified oils being in a diphasic system have a large oil-water interfacial area that exposes more of the oil surface to aqueous phase pro-oxidative factors. However, measurement of β-carotene in the previous sections has shown that the bioactive is better retained in encapsulated systems.

Figure 7.

Secondary oxidation products TBARS measured for (a) emulsions and, (b) their respective bulk oils stored in light and dark storage at 37 °C, n = 4.

Degradation kinetics

-

The degradation of β-carotene dissolved in oil and that dispersed in emulsified form was monitored in this study for a 25-d period with and without light exposure. The kinetic plots for zero, first and second order with corresponding R2 are presented in Tables 2, 3 & 4. From these tables, it can be seen that the best fit for β-carotene dissolved in bulk GTO and MCT oils is given by second-order kinetics. On the other hand, the best fit for β-carotene degradation dispersed emulsions is given by zero-order kinetics. The present results for dispersed systems are similar to those observed by Cornacchia & Roos[57] who observed β-carotene to exhibit zero-order kinetics in solid lipid particles and liquid lipid particles stabilized by whey protein isolate at 15 °C for 28 d.

Table 2. Zeroth order rate constants of β-carotene dissolved in oil and dispersed in emulsified form to storage in dark vs photodegradation.

Dark Light R2 k (μg mL−1 day−1) R2 k (μg mL−1 day−1) Oil MCT 0.726 9.13 0.632 9.13 GTO 0.675 8.18 0.648 8.47 Emulsions MCT 0.925 13.1 0.930 14.0 GTO 0.950 13.0 0.978 13.1 All samples were stored at an accelerated storage of 37 °C. Table 3. First order rate constants of β-carotene dissolved in oil and dispersed in emulsified form subjected to storage in dark vs photodegradation.

Dark Light R2 k (day−1) R2 k (day−1) Oil MCT 0.833 0.106 0.916 0.109 GTO 0.870 0.093 0.906 0.112 Emulsions MCT 0.746 0.119 0.943 0.152 GTO 0.800 0.102 0.904 0.143 All samples were stored at an accelerated storage of 37 °C. Table 4. Second order rate constants of β-carotene dissolved in oil and dispersed in emulsified form subjected to storage in dark vs photodegradation.

Dark Light R2 k (mL μg−1 day−1) R2 k (mL μg−1 day−1) Oil MCT 0.933 0.0006 0.979 0.0014 GTO 0.930 0.0008 0.985 0.0013 Emulsions MCT 0.699 0.0004 0.738 0.0018 GTO 0.768 0.0004 0.622 0.0018 All samples were stored at an accelerated storage of 37 °C. The majority of the storage studies that measured β-carotene over storage periods in food systems or encapsulated systems reported first order kinetics[51,58−60]. When the present results for bulk oils were fit to the first-order kinetic model, the fit was good but not the best. In the present trials with sunflower oil dissolved with β-carotene and stored in the dark at 37 °C, no specific trend was observed for bulk oil (Supplemental Fig. S3). Calligaris et al.[51] described degradation of β-carotene in bulk MCT oil kept under a storage condition of 20 °C for 14 d as pseudo-first order kinetics, after which β-carotene was not detected.

The present study attempted to eliminate the effects of antioxidants by selecting saturated medium-chain triglycerides, it is possible that the effect of fatty acid chain length of carrier oil has some part to play in encapsulated systems. Further studies that eliminate residual antioxidants as well as use oils with long-chain fatty acids as carriers may prove to further understand storage stability of β-carotene in encapsulated emulsions.

-

Multilayered emulsions of OSA-starch and chitosan were prepared by layer-by-layer deposition method. The polysaccharide based multilayered emulsions were found to be physically stable in heat treatments up to 121 °C for 60 min. β-carotene enclosed within emulsions were retained better than β-carotene dissolved in bulk oil during storage at 37 °C. Emulsions functioned as encapsulating structures of the oil phase and offered protection to the bioactive material β-carotene enclosed. The extent of the protection depended largely on the nature of the interfacial material and the presence of additional antioxidants in the system. Emulsified and oil-based systems composed of β-carotene were only slightly affected by exposure to light. However, perceived loss in color was more prominent in emulsions stored under light than in the dark. The reaction kinetics of emulsified β-carotene best fit the zeroth-order model and oil solubilized β-carotene best fit the second-order kinetic model.

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Sivabalan S, Sablani SS; methodology: Sivabalan S, Sablani SS; data curation: Sivabalan S, Sablani SS; formal analysis and visualization: Sivabalan S, Sablani SS, Ross C, Tang, J; writing-original draft: Sivabalan S; writing-review & editing: Sivabalan S, Sablani SS; Ross C, Tang J; funding acquisition and supervision: Sablani SS. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

-

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

This research was partially supported by the (USDA) National Institute of Food and Agriculture Research (Grant Nos 2016-67017-24597 and 2016-68003-24840), and Hatch project (#1016366). The authors thank Dr. Hanu Pappu and Dr. Sindhuja Sankaran for the use of the Ultrasonicator and Luxmeter.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Supplemental Fig. S1 lllustration of layer-by-layer electrostatic deposition for synthesis of secondary emulsion-2.5 % oil, OSA starch as primary emulsifier and chitosan as secondary emulsifier.

- Supplemental Fig. S2 lllustration of storage study at 37 °C where selected β-carotene loaded secondary emulsion along with bulk oil was exposed to light.

- Supplemental Fig. S3 Trend in β-carotene dissolved in bulk sunflower oil degradation during storage in dark, n ≥3.

- Supplemental Table S1 ANOVA table for storage parameters: For storage conditions, each data set had 3 source of variation (factors) and therefore, a 3-way ANOVA analysis was used to study the data. As indicated in the table, in all the data set studied, interactions were significant (green highlights) and therefore, single factor main effects are not to be interpreted.

- Copyright: © 2024 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of China Agricultural University, Zhejiang University and Shenyang Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Sivabalan S, Ross CF, Tang J, Sablani SS. 2024. Physical, thermal, and storage stability of multilayered emulsion loaded with β-carotene. Food Innovation and Advances 3(3): 244−255 doi: 10.48130/fia-0024-0022

Physical, thermal, and storage stability of multilayered emulsion loaded with β-carotene

- Received: 19 October 2023

- Revised: 17 June 2024

- Accepted: 29 June 2024

- Published online: 25 July 2024

Abstract: Carotenoids are colored bioactive substances increasingly used due to their antioxidant properties, vitamin A precursor role, and ability to function as a natural food color. Knowledge of carotenoid behavior during high-heat processing and subsequent storage in emulsified food matrix is essential to expand their application natural food colors and neutraceuticals. Firstly, the physical, thermal, and colloidal stability of emulsions constructed from octenyl succinic anhydride-modified starch (OSA starch)-chitosan multilayered interfaces were investigated. Results of charge reversal from −32.4 ± 1.9 mV to +38.0 ± 0.8 mV indicate that multilayered interfaces were formed in emulsions. As measured by Z-average size, the emulsions were stable after the thermal treatment at 121 °C for 60 min, thus demonstrating a novel heat-stable multilayered emulsion. Subsequently, a select multilayered emulsion was loaded with β-carotene, and its storage stability was assessed. The degradation of β-carotene in an oil-in-water emulsion was better described with zeroth order kinetics; β-carotene dissolved in bulk oil was better described using a second-order kinetic equation. The presence of an encapsulating material around the oil droplets loaded with β-carotene enhanced its stability, which makes it instrumental in extending shelf-life and maintaining a consistent appearance. The results can be used to predict the availability of β-carotene during storage.

-

Key words:

- β-carotene /

- Degradation kinetics /

- Accelerated storage /

- Multilayered emulsions /

- OSA starch /

- Chitosan