-

Meat and meat products occupy a prominent place in the human diet. With the economic recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, meat consumption is constantly increasing. A report jointly released by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) shows that meat supply will continue to increase over the next ten years. During this period, it is expected that global per capita meat demand will increase by 2% until 2032, especially, the production of pork and poultry is expected to increase significantly[1]. At present, plant-based meat analogs are continuously expanding their market share, but further exploration of their nutritional functions is needed[2]. Meat and meat products have high nutritional value and unique flavor characteristics, compared with plant-based proteins, animal-derived proteins have higher bioavailability, and their types and proportions of amino acids are closer to human needs[3]. The balanced intake of polyunsaturated fatty acids and saturated fatty acids can maintain the nutritional balance of the body[4]. Therefore, they are more easily absorbed by the human body and meet the nutritional and health needs of consumers. Reasonable intake of meat and meat products is crucial for the growth, development, and health of the body[5]. However, richer nutrients of meat and meat products also cause several safety issues, including foodborne pathogens (bacteria, viruses, parasites), chemical substances (heavy metal elements, illegal additives, etc.)[6]. In addition, the authenticity identification and freshness evaluation of meat are also important owing to growing requirements for meat quality. Therefore, monitoring hazard residues, authenticity, and freshness is necessary to ensure meat safety and quality.

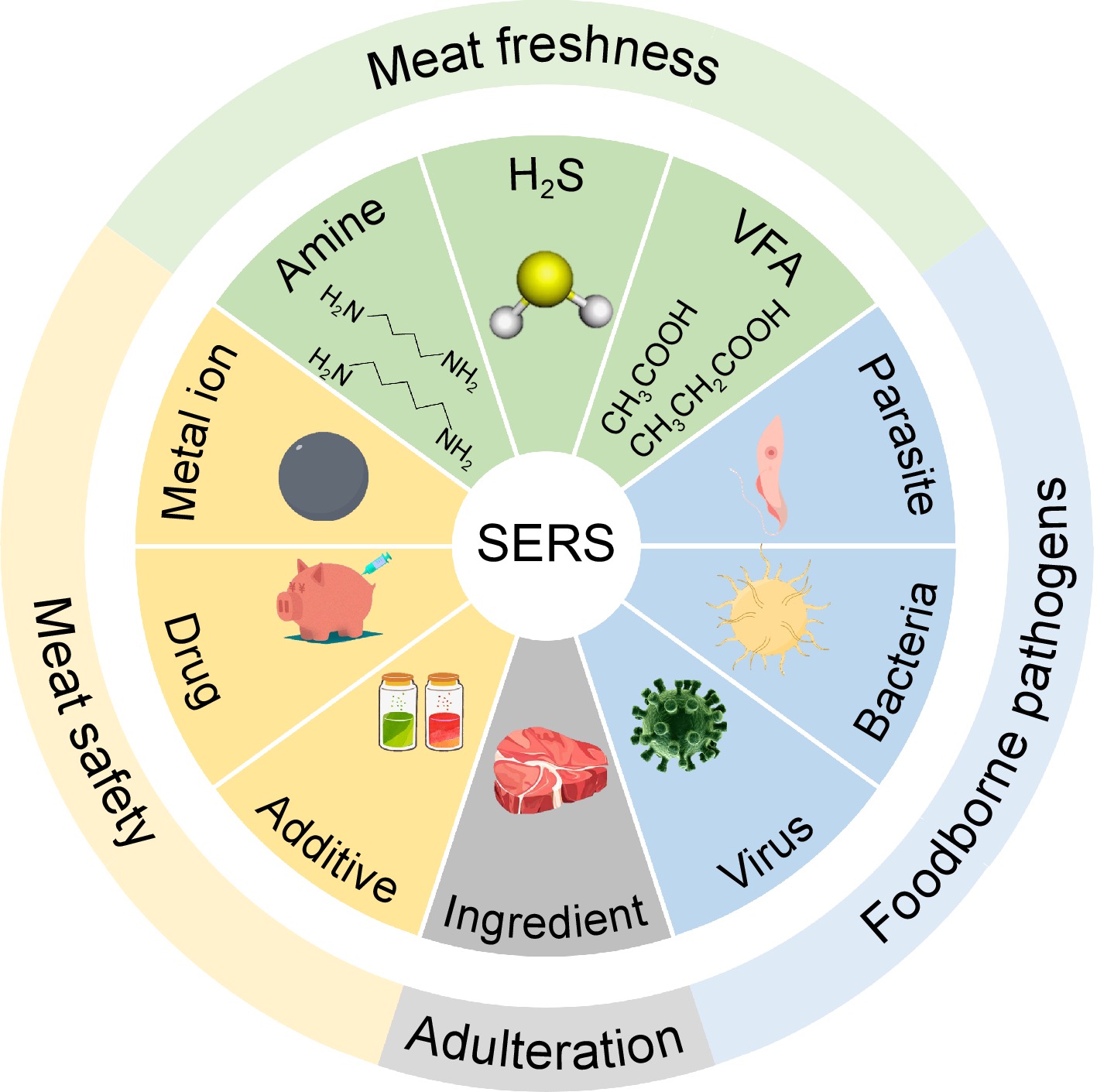

Meat and meat products are highly susceptible to contamination during processing, transportation, storage, and sale. For small molecule pollutants, traditional detection methods include gas chromatography (GC), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS)[7−9]. For microbial contamination, cultivation methods combined with molecular biology techniques or biochemical reactions are adopted[10,11]. Although these methods are of high accuracy, restrictive experimental conditions and long experimental cycles cannot meet the needs of the meat industry[12]. With the continuous development of detection technology, immunological techniques based on specific binding between antigen and antibody, including lateral flow immunochromatography assay (LFIA), enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and electrochemical biosensor technologies using nucleic acids, enzymes, and other recognition elements, are developing rapidly[13−15]. In recent years, with the application of chemometrics and machine learning technology, the spectroscopy technology for food safety detection is becoming increasingly widespread, which can achieve the goals of predicting and classifying food samples[16]. Among them, Raman spectroscopy, as a representative technique for detecting trace molecules can quickly achieve non-destructive testing of biological samples, promoting rapid detection in food safety analysis[17]. Raman scattering is inelastic scattering of object molecules under light radiation, in which the frequency of light waves would shift compared with incident light waves. By measuring this deviation, molecular information about the vibration and rotation of relevant molecules can be obtained, thereby achieving the detection and identification of the target. Although Raman spectroscopy technology has achieved simple, rapid, and fingerprinting detection, it still faces problems such as weak Raman signals[18,19]. Researchers have always been committed to enhancing Raman detection signals and exploiting other strengths. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) has been emerging as a predominant strategy to solve such problems by virtue of surface plasmon-resonance induced high signal enhancement effects and various enhancement manners[20]. The application of SERS in the detection of meat and meat products is shown in Fig. 1.

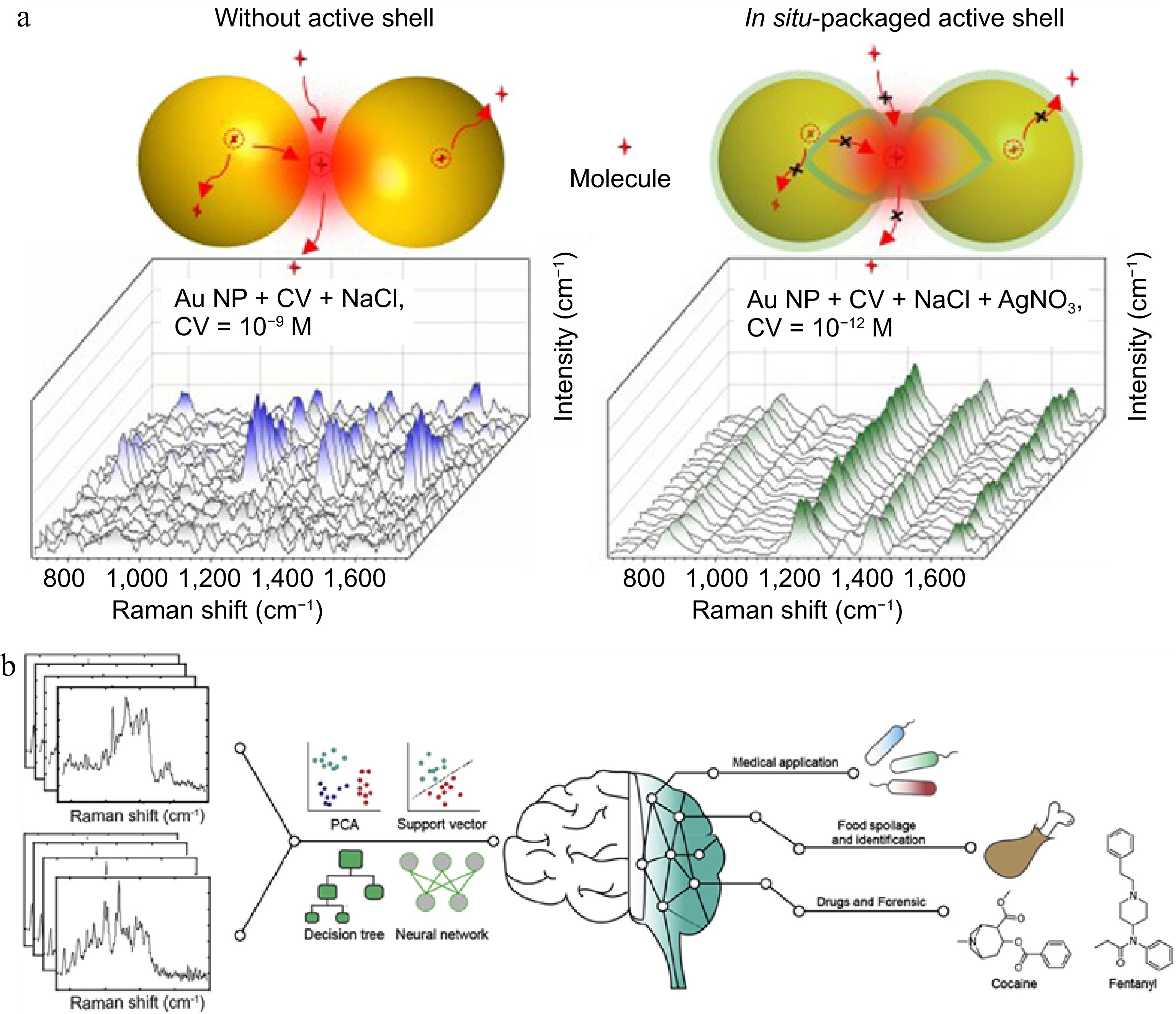

The complexity of matrices often leads to poor repeatability of Raman signals. To improve the repeatability and sensitivity of this technology, it is necessary to develop SERS substrates with stable plasmonic enhancement. Various SERS substrates have been developed. If classified by substrate properties, they can be divided into noble metal substrates and noble-free metal substrates[21]. From the view of practicability, the existing SERS substrates can be divided into colloidal substrates and solid substrates[22]. Colloidal substrates generally include single or multiple metal nanoparticles[23−25], showing better signal stability, while solid substrates exhibit higher signal amplification ability due to good morphology controllability[26]. Common forms of solid substrates include membrane substrate and self-assembled substrate[27,28]. The size, morphology, and material of SERS substrates have a significant impact on the enhancement of Raman signals[29]. For any SERS substrate, the widely accepted mechanisms for SERS enhancement effects are electromagnetic enhancement (EM) and chemical enhancement (CM), as shown in Fig. 2. The EM is excited by the strong electromagnetic field generated by surface plasmon resonance on ultrathin or nanostructured surfaces, thus enhancing the electromagnetic signal. The CM is induced by the formation of charge transfer complexes between adsorbed molecules and metal substrates, thereby achieving enhancement effects[30]. Due to its fast response speed, high sensitivity, and non-destructive detection ability, SERS has been widely applied in fields such as food safety analysis[31], environmental monitoring[32], and material science[33].

Figure 2.

Enhancement mechanisms of SERS[34].

SERS can be used in combination with various technologies, such as immunochromatography[35], molecular imprinting technology[36], colorimetric technology[37], etc., to improve selectivity, sensitivity, and detection efficiency. General SERS detection strategies are labeled and label-free detection modes in terms of detection of indirect and direct detection of the target. The former can detect Raman signals of targets without labeling or special processing, not only providing the inherent molecular information but also making the detection process simpler. However, it is limited by the concentration and complexity of the detection system[38,39]. The latter can reflect the analyte by strong Raman characteristic signals of SERS tags. With the aid of recognition elements like antibodies[40], aptamers[41], and molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs)[36], the labeled method can achieve the detection of various targets.

Different from other spectroscopy techniques, SERS can provide a highly sensitive fingerprint analysis, amplify the Raman signal of the analyte without fluorescence background interference, and match various laser conditions and different types of instruments including large high-resolution workstations and portable devices. Therefore, SERS has now developed into a powerful platform for quickly detecting trace extrinsic or harmful substances in meat and meat products. Compared with previous reviews, this review focuses on two SERS detection modes and their related applications in meat and meat products. SERS detection is divided into labeled detection and label-free detection to compare their advantages and disadvantages. Then, the research progress of SERS in detecting several hazards such as foodborne pathogens and veterinary drug residues are summarized, and the practicability of this technology in identifying meat adulteration and spoilage discussed. Finally, a perspective of SERS to more efficiently and sensitively meet the requirements of rapid and high-throughput detection in the meat industry is provided.

-

In the label-free SERS detection mode, the active substrate of SERS can directly bind to the analyte without additional signal indicators to assist detection[42]. The spectral information provided by this method can not only be used for the detection of the substance under test, but also for analyzing the structural information or fingerprinting of biomolecules[43,44]. Arabi et al.[45] proposed a mussel-inspired surface imprinted capillary sensor that can quickly and sensitively detect proteins. The universal sensor was not limited by pre-processing and operator skills. Xu et al.[46] used iodide-modified Ag nanoparticles (Ag IMNPs) to achieve label-free detection of single stranded DNA molecules. This detection strategy not only significantly improved Raman signals, but also reduced the probability of biological molecule denaturation during the detection process. Wang et al.[47] combined chemometric methods to achieve label-free detection of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which played an important role in the detection of bacterial resistance and identification of resistant strains. To detect antibiotic residues in serum, Wang et al.[48] modified nanoparticles with bromide ions and used peak intensity changes as a basis for distinguishing different antibiotic molecules. This method is of great significance in drug detection. Zhang et al.[49] designed a SERS microfluidic chip for drug detection, providing a new platform for efficient detection of 6-thioguanine (6-TG) in human serum.

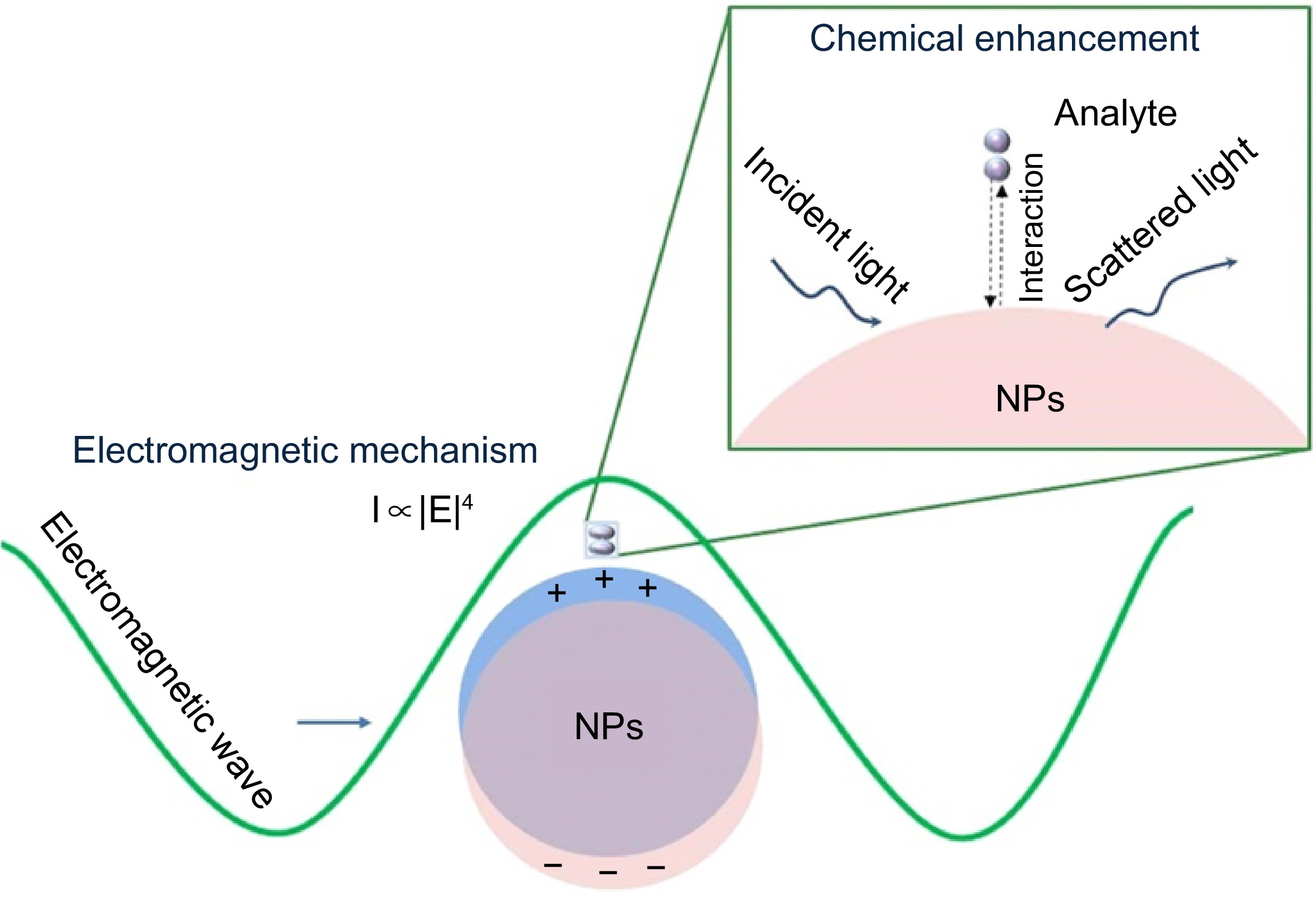

In label-free SERS detection, the binding mode and interaction mechanism between the tested substance and the SERS substrate are worth exploring in depth, which often determines the sensitivity and signal of the detection system[42] The strategies for anchoring the tested molecule mainly include biomolecular recognition[47], non covalent bonding[50], and electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions[51]. Zhang et al.[52] used single-molecule surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SM-SERS) to investigate the phenomenon of signal fluctuations caused by the adsorption and desorption of molecules near hot spots. They utilized active nanoshells to confine and anchor molecules onto the surface of plasmon nanoparticles, significantly improving the sensitivity and reproducibility of single-molecule detection (Fig. 3a). Meanwhile, combining the detected spectral data with chemometrics and machine learning methods enables more effective data analysis[53]. Raman spectroscopy data is rich and complex, with the assistance of machine learning and chemometric methods, data processing, including noise reduction and interference elimination, can be quickly achieved[54,55] (Fig. 3b). There are a wide range of applications in food analysis[56], and biomedicine[57].

Labeled detection

-

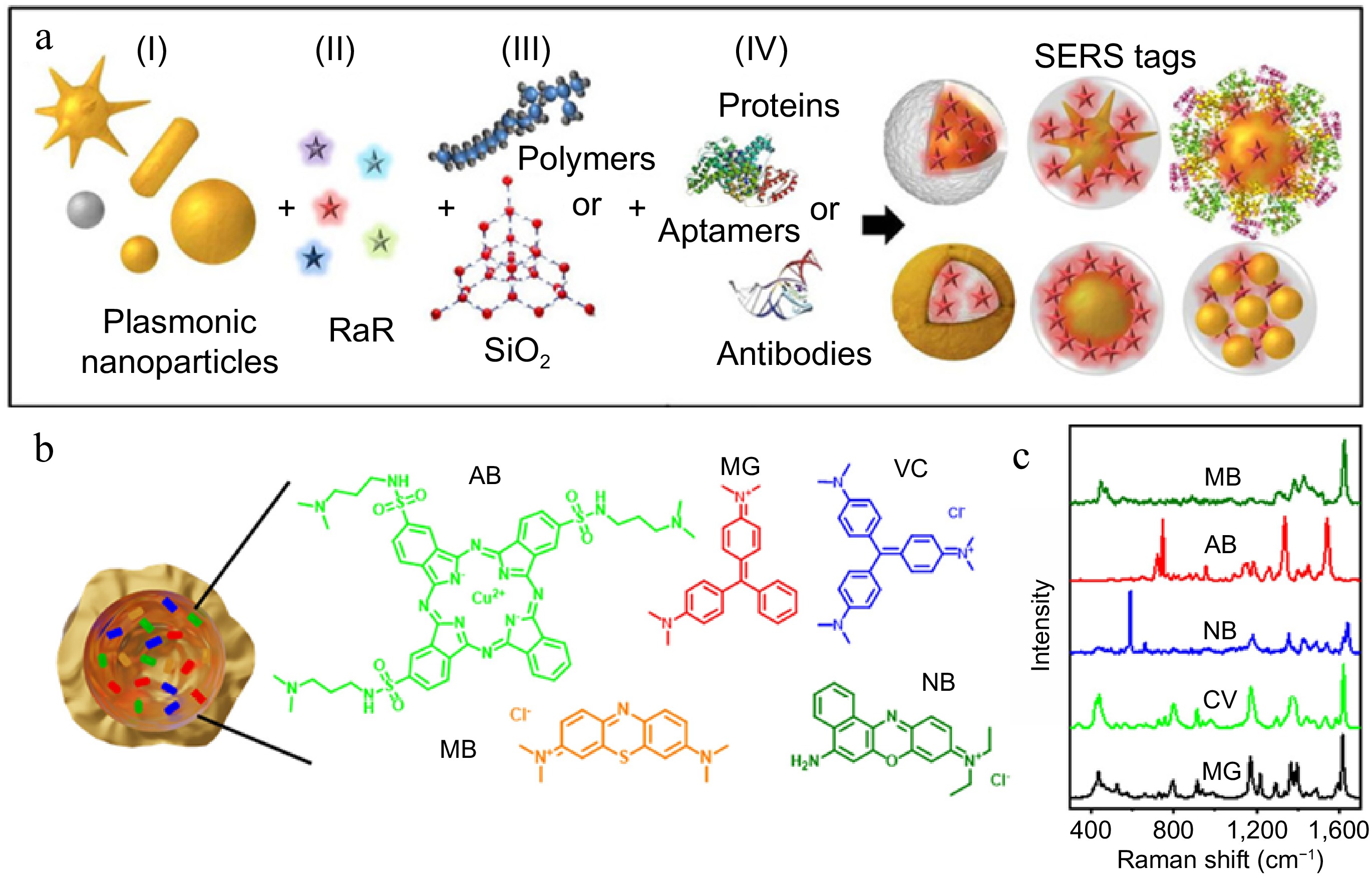

When the composition of the matrix to be tested is complex or physical characteristics such as temperature and pH need to be monitored, label-free detection has significant limitations compared to labeled detection[58]. The labeled SERS detection method relies on functionalizing Raman reporters with high sensitivity, specificity, and selectivity. By observing the Raman shift and intensity changes of characteristic peaks in the Raman spectrum, the presence and amount of the tested substance can be reflected by Raman reporters[59]. Although the labeled mode cannot reflect rich intrinsic biological information, multiple SERS tags might have a potential in multiplex analysis[34].

SERS tags need to have ultra-high sensitivity, specificity, and photostability[60]. Typically, SERS tags consist of four parts: plasmonic nanoparticles, Raman reporters, coating layers, and targeting ligands[61] (Fig. 4a). As SERS substrates, plasmonic nanoparticles are activated by localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) to enhance the signal. Raman reporters with excellent properties are adsorbed on the surface of the SERS substrate, and then encapsulated with a protective layer to make the particles more stable. Finally, targeting ligands such as antibodies and aptamers are connected to form SERS tags[62]. Raman reporters can be mainly divided into three categories, specifically including dye molecules containing nitrogen or sulfur-like crystal violet (CV)[63] (Fig. 4b & c), thiol molecules like 4-mercaptobenzoic acid (4-MBA)[64], and 4-mercaptophenylboronic acid (4-MPBA)[65]. Alkyne molecules possessing unique peaks in Raman silent regions that attract emerging attention on SERS due to largely reduced background interference[66]. To enhance the stability and signal strength of SERS tags, dual signal molecules for the detection of biomolecules are used[67]. The dual signal method can not only reduce the influence of external interference and improve the repeatability of detection but is also suitable for the detection of low concentration analytes in complex samples[68]. In terms of dual signal, one serves as an internal standard signal and the other as a response signal, which can reduce detection errors and have higher detection accuracy compared with single signal systems. Tan et al.[69] used 5,5'-dithiobis (2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) as the internal standard signal, 6-carboxyl-Xrhodamine (ROX) as the response signal, and the double signal based SERS sensor detected the miR-21 of human serum samples, with a detection limit of 0.046 pM. It has broad application prospects in the early diagnosis of breast cancer.

Liu et al.[70] combined SERS with LFIA and proposed a biosensor for detecting anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgM/IgG. This sensor used DTNB as a Raman reporter modified on silica nanosphere coated with an Ag shell, to provide a sensitive detection strategy for rapid screening of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Jiang et al.[71] synthesized Fe3O4@TiO2-based SERS tags using DTNB as the Raman reporter, achieving in situ detection of exosomal miRNAs. Zhu et al.[72] embedded 4,4'- dipyridyl (DP) into AuNPs and silica shell to prepare SERS probes with excellent stability and specificity, achieving ultrasensitive detection of E. coli O157:H7. Combined with hybridization chain reaction (HCR), Peng et al.[73] used 4-ethynylbenzaldehyde (EBA) and two different structures of HCR sequences as SERS tags, developing a novel SERS sensing method and achieving sensitive detection of hepatitis C virus (HCV) nucleic acid.

-

According to statistics from the World Health Organization (WHO), approximately 600 million people are infected with foodborne diseases[76], largely increasing the burden on the healthcare system. Meat and meat products are important sources of high-quality protein for the human body, and due to its rich nutritional content, meat is often contaminated by foodborne pathogens and bacteria[77]. The bacteria pollution sources of meat products can be divided into two categories: endogenous and exogenous pollution. The former usually refers to pollution caused by microorganisms carried by livestock and poultry, while the latter often refers to microbial pollution present in the processing and circulation process[78]. Common foodborne pathogenic bacteria in meat and meat products include L. monocytogenes, Salmonella, E. coli, etc.[79]. Consuming meat contaminated with foodborne pathogenic bacteria poses a serious threat to human life and health. Therefore, to control the occurrence of foodborne diseases and protect the development of the meat industry, it is crucial to establish sensitive and rapid methods for detection.

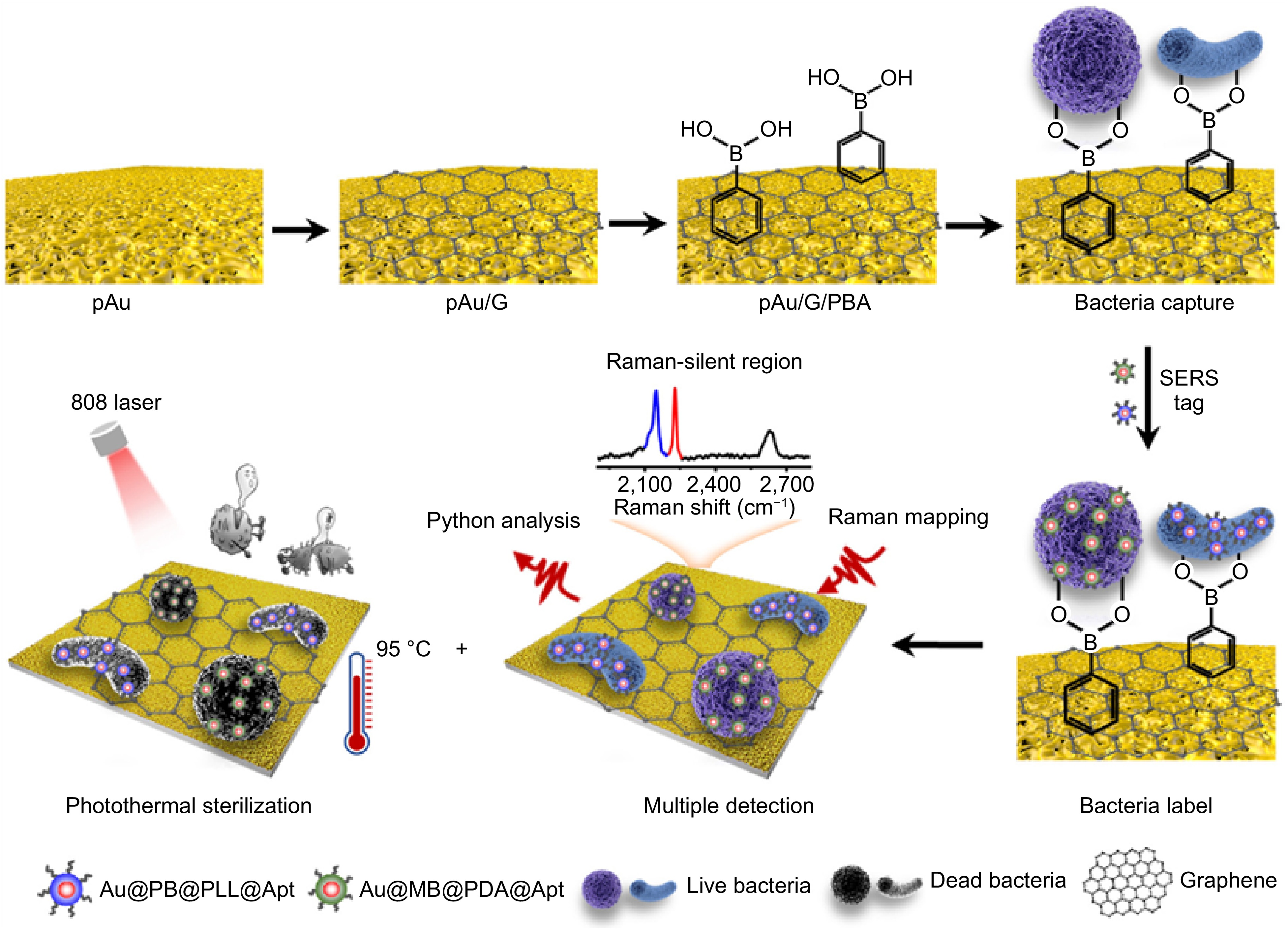

At present, foodborne pathogenic bacteria can be detected through the following three strategies. Physiological and biochemical testing can indicate the presence of pathogens through chemical signals, such as the ATP bioluminescence method[80]. Immunological testing is based on specific binding of bacterial antigens followed by signal amplification, such as ELISA[81]. Molecular testing relies on nucleic acid-based hybrid and amplification, such as PCR[82]. Compared with traditional plate culture methods, these methods have achieved sensitive and accurate detection of pathogens, however, they still face several drawbacks including slower detection speed, longer detection cycles, and more operation steps[83]. Due to the multiple advantages of SERS, the technology has been widely used to detect foodborne pathogens. Yang et al.[84] reported a surface cell imprinting (SCIS) method to capture the target pathogens followed by SERS mapping detection with a nanosilver modified by 4-MPBA (4-MPBA@AgNPs) as the SERS tag. It has achieved specific and quantitative determination of E. coli in chicken breast samples, with a linear range of 102−108 CFU/mL and a detection limit as low as 1.35 CFU/mL. By changing the bacterial cell imprinting substrate, this platform can also be used for the detection of other bacteria. Cho et al.[85] proposed using membrane filtration and immunomagnetic separation techniques to capture and enrich target bacteria. Using 4-MBA modified AgNPs as SERS tags, 10 CFU/mL of E. coli O157:H7 was detected in ground beef within 1 h. In label-free detection mode, the Raman signal of the analyte mainly comes from the surface chemical composition and metabolites, but some bacteria have similar cell wall components, resulting in high similarity in their SERS fingerprint spectra. On the other hand, the amount of spectral information data is too complex to distinguish. In this case, mathematical-statistical analysis methods and chemometrics methods should be combined to eliminate signal interference during the detection process and achieve efficient detection of foodborne pathogens[86,87]. Leong et al.[88] used a SERS-based surface chemistry classification method, in combination with machine learning, to classify six types of bacteria by layering surface charges, biochemical features, and the types and quantities of functional groups. The accuracy was up to 98%, and the relationship between bacterial extracellular matrices (ECMs) surface features and SERS fingerprint spectra were successfully made. Eady et al.[89] compared traditional plate culture and PCR methods and confirmed that combining SERS with support vector machine (SVM) could realize rapid detection and accurate classification of Salmonella typhimurium in chicken rinse. In addition, Zheng et al.[90] utilized python assisted SERS chips to achieve photothermal inactivation of Salmonella typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus in blood samples, avoiding the problem of secondary contamination during the detection process (Fig. 5). The related analytical peformances of these methods were compared in Table 1.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of capturing, detecting, and inactivating bacteria[90].

Foodborne viruses

-

Foodborne viruses that exist in various foods might cause diseases such as viral gastroenteritis and hepatitis in humans. Patients often suffer from acute vomiting and diarrhea due to ingestion of contaminated water or food[91]. Common foodborne viruses in meat and meat products include avian influenza virus, norovirus, hepatitis E virus, and rotavirus[92]. PCR is a classical technique for virus infection identification with high sensitivity and accuracy but requires complex sample pretreatment and expensive equipment[93]. In addition to PCR, immunological methods such as ELISA are also commonly used for virus detection[94]. However, the sensitivity and accuracy of this method are not as good as nucleic acid amplification technology[95]. Therefore, SERS-based methods were developed for the efficient detection of foodborne viruses. H5N1 is a highly pathogenic and deadly subtype of avian influenza virus[96]. Wang et al.[97] used an unlabeled SERS method, using AgNPs as the substrate, to achieve rapid detection of influenza A (H5N1) subtype influenza virus in chicken embryos, by forming specific sandwich immunocomplexes, with high accuracy and strong specificity. This provided a reference basis for the simple and rapid detection of various infectious viruses. Sun et al.[98] proposed a magnetic immunosensor labeled with 4-MBA for the detection of avian influenza virus H3N2. The sensor had the advantages of high sensitivity and rapid detection. Therefore, this method had the potential to be applied to the detection of avian influenza virus in other real biological samples. Wang et al.[99] designed and synthesized a novel magnetic tag with excellent signal amplification performance. The SERS-LFIA system was used to detect HAdV and H1N1, and it was found that this method had high sensitivity with detection limits of 10 and 50 PFU/mL, respectively, and could be used in real biological samples such as human whole blood, serum, and sputum. The related analytical peformances of these methods were compared in Table 1.

Veterinary drug residues

-

To prevent and control animal diseases, veterinary drugs, mainly include antibiotics, antiparasitic, and antifungal drugs, hormones, and anti-inflammatory drugs, have long been applied during livestock feeding[100]. The use of veterinary drugs often bring profits to animal producers and reduce losses. However, residual veterinary drugs in animal bodies may have many negative impacts on the animals themselves and consumers who consume them, including the development of drug resistance in both animal and human bodies, affecting the functioning of the immune system and the diversity of gut microbiota[101]. Before detecting veterinary drug residues, it is necessary to perform sample pretreatment to reduce external interference, which is closely related to the accuracy and precision of the detection[102]. Currently, common methods such as solid-phase extraction (SPE) and solid-phase microextraction (SPME) are used to separate the analyte from the complex sample matrices[103,104]. Even so, the sample solution after enrichment is still so complex as to direct detection and identification, thus gas/liquid chromatography (GC/LC) followed by mass spectrometry (MS) is necessary.

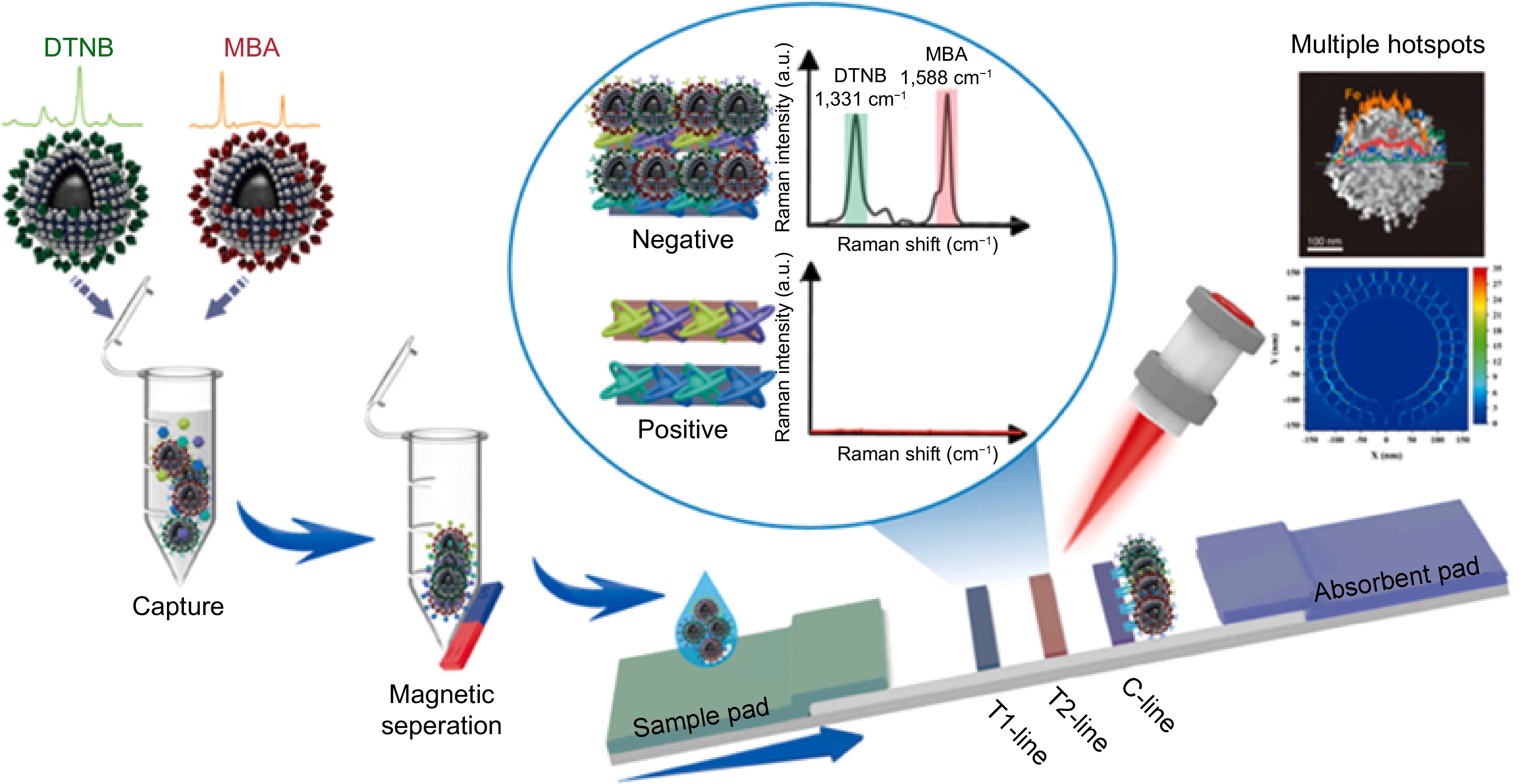

It is worth mentioning that SERS has outstanding potential in detecting residual harmful chemical components. Peng et al.[105] used AuNPs as substrates to detect benzylpenicillin potassium (PG) and explored the effects of Au substrates and reporter adsorption on SERS intensity. Finally, the established method was applied to the detection of PG in duck meat. Zhao et al.[106] used OTR202 (AuNPs) and OTR103 (gold colloid enhancement reagent) as SERS substrates, combined with adaptive iteratively reweighted penalized least squares (air-PLS) to remove fluorescence and background signals, and the detection limit was down to 1.120 mg/L, achieving rapid detection of tetracycline residues in duck meat. Zhao et al.[107] established a method for determining marbofloxacin using SERS based on β-cyclodextrin-modified silver nanoparticles (β-CD-AgNPs) with a detection limit of 1.7 nmol/L. In chicken and duck samples, the spiked recovery rate of marbofloxacin ranged from 101.3% to 103.1%, providing a solution for reliable on-site detection in the future. To reduce spectral interference from other substances in food matrices, combining SERS with other separation techniques is a good choice. Shi et al.[108] used thin-layer chromatography combined with SERS, namely TLC-SERS, to achieve simultaneous and rapid (< 10 min) detection of 14 nitroimidazole compounds in pork with a detection limit of 0.1 mg/L. Based on the magnetic SERS-LFA system, Tu et al.[109] synthesized SERS tags using DTNB and 4-MBA as dual Raman reporters, combined with specific antibodies. They utilized the dual signal amplification effect of numerous stable hotspots and magnetic enrichment to detect the residues of four veterinary drugs in pork. This method achieved trace detection at the pg/mL level within 35 min, effectively improving the sample detection signal and sensitivity, and had great prospects in the detection of harmful small molecules (Fig. 6). The related analytical peformances were compared in Table 1.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of using the SERS-LFA system to detect multiple veterinary drugs[109].

Food additives

-

Food additives are artificially synthesized or natural substances that can improve the sensory characteristics and quality of food. The application of food additives has played a great role in the development of the food industry. To improve the flavor, texture, nutrition, and extend the shelf life of meat products, several food additives include antioxidants, preservatives, colorants, and acidity regulators are applied during meat processing and storage[110]. However, unscrupulous retailers, in pursuit of commercial interests, abuse food additives, and even engage in the illegal use of preservatives, colorants, and other substances with maximum amount limits in meat product production, such as the abuse of nitrite, composite phosphates, and sodium benzoate. Unreasonable uses of food additives have also brought about a series of food safety issues, posing a great threat to the life and property safety of consumers[111]. At present, the main detection methods for food additives include spectroscopy[112], chromatography[113], and electroanalysis[114]. Meanwhile, the sampling and pretreatment steps have a considerable effect on detection accuracy[115].

For several common food additives, SERS also exhibits satisfactory potential[116]. Nitrite, as an essential food additive in meat processing, is often used as a preservative and coloring agent, but it might cause certain health risks, thus being necessary to develop a rapid SERS detection method[117]. Zhang et al.[118] enhanced the SERS signal of nitrite by introducing 4-aminothiopenol capped AgNPs decorated halloysite nanotubes (HNTs-AgNPs4−ATP), thereby achieving the detection of nitrite ions in sausages and pork luncheon meat. This method achieved in-situ derivatization and selective determination of nitrite ions in meat products through labeled SERS. The effective dispersion and deposition of metal nanoparticles play an important role in maintaining substrate stability and improving SERS performance[119]. Zhang et al.[120] developed a SERS platform for the rapid detection of nitrite using electrospinning-assisted electrospray technology. The use of this technology is of great significance for the effective deposition of certain shaped metal nanoparticles into SERS layers. The platform had good selectivity, stability, and anti-interference ability, and the detection limit was about 15.29 ng/L, realizing the detection of nitrite in chicken sausage, canned pork, bacon, and ham. Liang et al.[121] combined hydrogel materials with SERS technology to prepare a sensor for detecting the concentration of sodium nitrite, and introduced machine learning to analyze data and predict results. The minimum detection limit reaches 3.75 mg/kg, realizing the quantitative determination of sodium nitrite in the extracts of bacon, lunch meat, and ham slices. The analytical peformances were compared in Table 1.

Illegal additives

-

In recent years, food safety accidents caused by illegal additives have aroused public attention to food quality and safety. Compared with the abuse of food additives, illegal additives have more serious implications owing to their severe toxicity to both livestock and the human body. Illegal additives mainly include melamine[122], malachite green[123], receptor agonist[124], and other substances, which are usually used to fraudulently increase nutrient content or preserve freshness[23]. The most common illegal additives in meat and meat products include β-adrenergic receptor agonists (clenbuterol hydrochloride[123], ractopamine[125], etc.) in pork, beef, mutton, and animal liver, nitrofuran drugs in pork and poultry[126], and synthetic pigments such as acid orange in meat products[127]. At present, commonly used detection methods for illegal additives include gas chromatography[128], mass spectrometry[129], ELISA[130], etc. With the continuous development of SERS substrates, Yan et al.[131] prepared transparent SERS substrates using anodic aluminum oxide (AAO) template method for direct detection of residual ractopamine on pork without the need for pretreatment. This method achieved the detection of trace amounts of ractopamine in meat samples with a detection limit of 10−8 M, and also opened up a new way for the direct measurement of other trace chemical substances on the surface of food. The uniform core-shell structure of nanomaterials significantly improves the SERS performance in signal enhancement and stability by increasing loading and reducing aggregation, which can improve detection efficiency and reliability[132,133]. Su et al.[134] designed a core-shell structure as a multifunctional tag and used the dual model colorimetric/SERS-LFIA for the detection of clenbuterol. This method increased the sensitivity of the detection system and stronger colorimetric reaction through antigen antibody specific binding, achieving quantitative detection of clenbuterol in pork, chicken, and sausages with a detection limit as low as 0.05 ng/mL. Xie et al.[127] realized the rapid detection of acid orange II in braised pork by synthesizing new core-shell nanomaterials including SERS substrates of Fe3O4@Au. In combination with machine learning methods, they verified the correctness of the detection results and compared with the results of HPLC, showing that this method can be used as an alternative to conventional HPLC methods for the detection and analysis of acid orange in food. The related analytical peformances of these methods were compared in Table 1.

Biotoxins

-

Biotoxins are a class of toxic substances produced by various organisms such as Clostridium, E. coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and the common biotoxins in meat and meat products are botulinum toxin and shiga toxin. Biotoxins often cause acute or chronic poisoning in the human body and have become a major threat in fields such as food and medicine[135]. The detection of food biotoxins typically involves quantitative analysis using ELISA[136], MS[137], and HPLC[138]. Nowadays, biosensors based on SERS have become an important analytical method for biotoxin detection. Subekin et al.[139] developed an aptasensor based on silver nanoislands as a SERS substrate for rapid detection of type A botulinum toxin. Due to its ability to recognize molecules and serve as Raman tags, the sensor has high specificity and good reproducibility, with a detection limit of 2.4 ng/mL, and can achieve rapid detection of botulinum toxin in complex matrices. Kim et al.[140] synthesized three-dimensional magnetic beads modified with gold nanoparticles and developed a SERS-based magnetic immunoassay for rapid and sensitive detection of botulinum toxin. The detection limit of this technology for type A and type B botulinum toxin reached 5.7 ng/mL (type A) and 1.3 ng/mL (type B). The proposed method is a low-cost and efficient detection technology for botulinum toxin and promising for other trace biotoxin detection in meat. Jia et al.[141] developed a biosensor with SiO2@Au/DTNB as the SERS tag that can simultaneously detect ricin, staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB), and type A botulinum toxin (BoNT/A) by combining SERS with LFIA. This technology achieved rapid on-site detection of three toxins with good repeatability and specificity, and was capable of application in clinical medicine. The analytical peformances were compared in Table 1.

Table 1. Applications of SERS in detection of meat hazards and additives.

Detection object SERS substrate Method LOD Ref. Foodborne pathogens E. coli O157:H7 AgNPs SERS-SCIS 1.35 CFU/mL [84] E. coli O157:H7 AuNPs SERS 10 CFU/mL [85] Salmonella typhimurium AgNPs SERS-SVM / [89] Salmonella typhimurium and Staphylococcus aureus pAu/G SERS-Python / [90] Foodborne viruses H5N1 AgNPs SERS 5.0 × 10−6 TCID50/mL [97] H3N2 AuNPs SERS 102 TCID50/mL [98] HAdV, H1N1 AgNPs SERS-LFIA 10, 50 PFU/mL [99] Veterinary drug residues Benzylpenicillin potassium AuNPs SERS / [105] Tetracycline OTR202-OTR103 SERS-air PLS 1.120 mg/L [106] Marbofloxacin AgNPs SERS 1.7 nmol/L [107] Nitroimidazoles AuNPs SERS-TLC 0.1 mg/L [108] Multiple veterinary drugs Au@AgNPs SERS-LFA 0.52–6.2 pg/mL [109] Food additives Nitrite ions AgNPs SERS 0.51 μg/L [118] Nitrite AgNPs SERS 15.29 ng/L [120] Sodium nitrite AuNPs SERS 3.75–8.11 mg/kg [121] Illegal additives Acid orange II AuNPs SERS-DFT 1 μg/mL [127] Ractopamine AgNPs SERS 10−8 mol/L [131] Clenbuterol Au/AuNS SERS-LFIA 0.05 ng/mL [134] Biotoxin Botulinum neurotoxin type A AgNPs SERS 2.4 ng/mL [139] Botulinum toxins A and B AuNPs SERS 5.7 ng/mL (A), 1.3 ng/mL (B) [140] BoNT/A AuNPs SERS-LFIA 0.1 ng/mL [141] Quality control

Meat adulteration

-

Meat adulteration is a fraudulent behavior of unscrupulous merchants who mix low-quality meat or non-meat substances into high-priced meat or its products to seek extra profits. Such behavior usually includes species or variety adulteration, production source adulteration, and production process adulteration[142,143]. Meat adulteration might be related to the changes in supply and demand, as well as the cost of animal husbandry and processing. However, this trickery has had a serious negative effect on the meat industry and hidden unknown safety issues. The food safety issues caused by meat adulteration are worrying. The adulterated meat might contain unknown species, pathogens, and veterinary drugs, which may not only directly affect the life and property safety of consumers but also involve religious issues and affect market stability[144,145]. The existing detection methods for meat adulteration mainly include nucleic acid detection technology[146], biosensors[147], spectroscopic detection technology[148], immunological detection technology[149], and mass spectrometry technology[150]. Currently, the detection methods for meat adulteration can be divided into non-destructive and destructive testing[151]. Non-destructive testing techniques include near-infrared spectroscopy[152], hyperspectral imaging[153], etc. Destructive testing techniques include detection based on nucleic acid[154], and protein[155]. As a non-destructive detection method, SERS has been applied in meat fraud detection. Liu et al.[156] proposed a novel detection strategy mediated by CRISPR/Cas12a followed by SERS, which could convert the target nucleic acid concentration into a visual signal for meat adulteration detection, achieving the detection of low adulteration rate samples in complex food matrices. Khalil et al.[157] designed an ultrasensitive dual nano platform SERS biosensor, namely the graphene oxide gold nanorod (GO AuNR) and gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), which could qualitatively and quantitatively detect DNA from any source. This sensor could replace traditional pork DNA detection methods, helping to more efficiently address the issues of authenticity and species origin in meat products. Khalil et al.[158] also developed a DNA biosensor for SERS that could quantitatively detect two types of meat simultaneously. The detection principle lies in the covalent conjugation between the signal probe and the capture probe. When the target sequences of two species are fixed simultaneously, the hybridization between the probe and the target achieves signal enhancement. This sensor used a SERS activity dual platform to increase detection sensitivity, with strong selectivity and specificity. As an emerging technology, SERS is still lacking in research on meat adulteration detection.

Existing research mainly focus on the detection of species sources, and further development is needed for cases of determining the authenticity of production areas and processes. To fully explore Raman spectrometry, new data mining technologies such as machine learning should be introduced to identify adulteration. Besides, the development of portable detection devices to achieve real-time on-site assessment is another future research trend.

Freshness determination

-

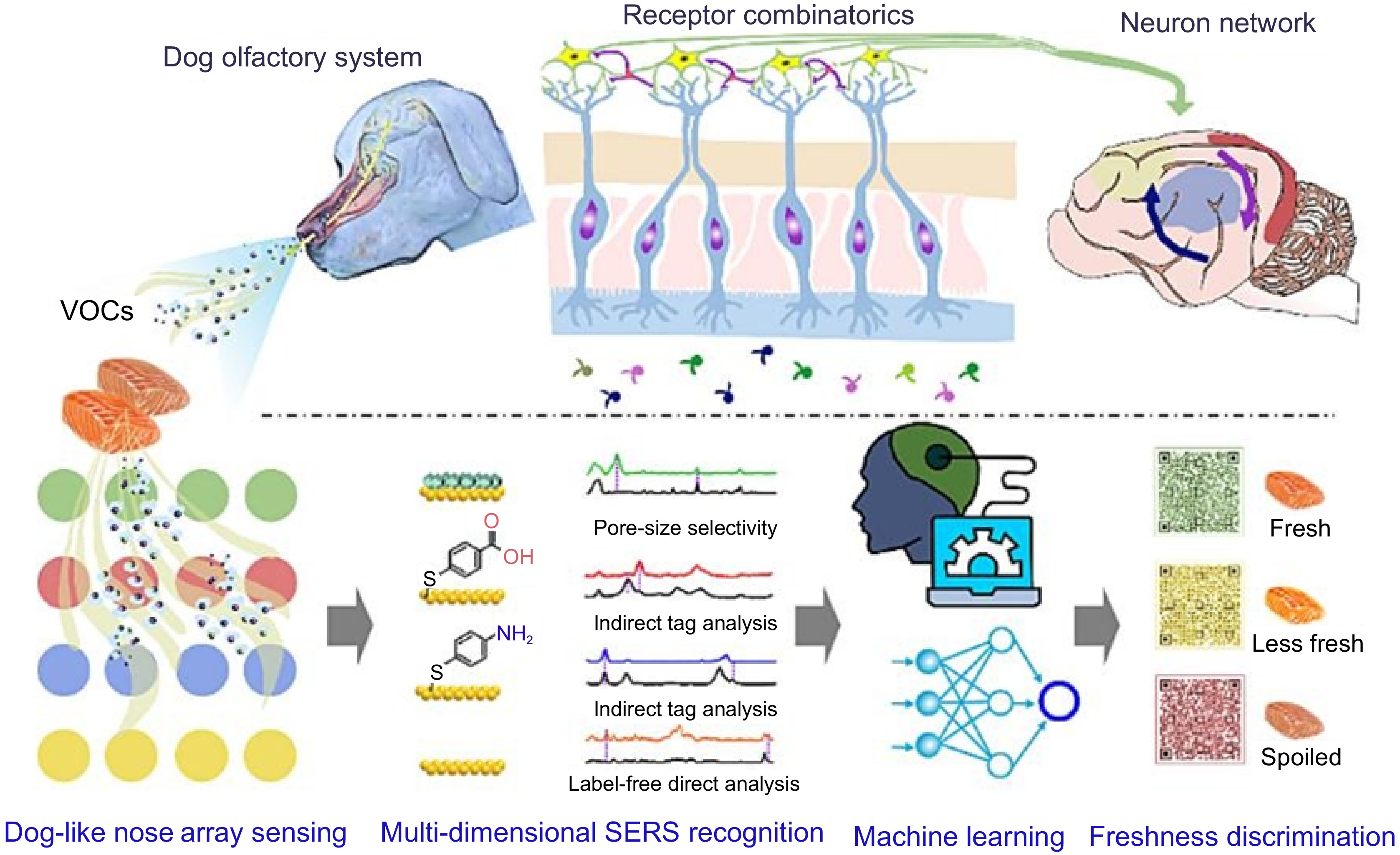

Meat contains abundant nutrients, making it an ideal place for microbial reproduction. The presence of microorganisms and some endogenous enzymes often leads to a decrease in the freshness of meat and eventual spoilage. The decrease in freshness of meat can be judged by changes in color, which not only leads to the disposal of meat and resource waste but also poses health risks such as pathogens and toxins[159,160]. With the improvement in disposable income, consumers are paying increasing attention to the freshness of foods. The traditional methods for determining freshness include sensory evaluation, chemical index detection, and microbial detection[161]. However, these methods all have some limitations. Sensory evaluation methods require specialized evaluators and the judgment results are always subjective. For chemical indicators such as total volatile base nitrogen (TVBN) and microbial detection, the detection methods are cumbersome and time-consuming, and cannot meet the needs of contemporary food industry[162]. Therefore, it is crucial to develop an efficient and sensitive non-destructive testing method that can measure the freshness of products. At present, several advanced methods for determining freshness include fluorescence spectroscopy[163], near-infrared spectroscopy[164], and visual intelligent packaging technology[165]. Notably, food freshness detection technology based on SERS has been widely reported. Qu et al.[166] achieved the detection of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in chicken samples, including bacterial metabolites, H2S, aldehydes, and biogenic amines, by integrating array sensors and combining machine learning, thereby achieving real-time determination of their freshness (Fig. 7). Given that cadaverine and putrescine are toxic biogenic amines produced by microorganisms, posing a significant threat to human health and food security, Sun et al.[167] utilized p-MBA functionalized SERS substrates to capture the analyte molecules through amide reactions, enabling trace detection of amine substances in pork samples, which is of great significance for detecting the degree of food spoilage. Kim et al.[168] designed a SERS paper platform coated with a metal-organic framework (MOF) that could effectively recognize volatile amine molecules, and this paper's sensory has been successfully applied to the freshness determination of chicken, beef, and pork samples.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of a scalable plasma array gas sensor for multi-dimensional SERS recognition[166].

-

With the rise in public awareness of food safety and human health, meat safety, and quality have received unprecedented attention. SERS, as an ultrasensitive detection technique, can achieve trace analysis of target analytes. Besides, the rapid and high-resolution detection characteristics of SERS make it suitable for on-site detection and multiplex analysis. This review focused on the development of the application of SERS technology in safety detection and quality assessment of meat and meat products. First, both label-free and labeled SERS detection modes were summarized, and labeled mode was predominant owing to higher sensitivity and various forms. Then, the application of SERS in foodborne pathogens, veterinary drug residues, food additive abuse, illegal additive use, and detection of biotoxin in meat and meat products were introduced. Meanwhile, the progress of SERS-based meat adulteration and freshness identification were discussed. However, SERS also faced some existing problems, such as poor reproducibility of detection results, weak resistance to external interference, and difficulty in enriching analytes. For future research, the following points can be underlined to promote the further development and application of SERS technology in the detection of meat and meat products: (1) Combining SERS with other technologies. SERS, as a sensitive detection method, relies on appropriate pretreatment operations to improve the accuracy and precision of detection; (2) Expanding SERS research on heavy metal ion pollution detection in meat and meat products by combining elemental analysis techniques, and boosting research on adulteration identification and freshness detection of meat and meat products; (3) Combining machine learning and chemometrics methods to mining Raman spectroscopy data and improving automatic detection and smart sensing. With the continuous development of material and data science, researchers will further study novel SERS substrates, SERS tags, and SERS instruments to improve the stability and repeatability of this technology, paving the foundation for safety and quality assessment in the meat and food industry.

This review was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22327804 and 22004064).

-

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception: Wu M, He H; draft manuscript preparation: Wu M; manuscript revision: He H. Both the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

-

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analyzed in this study.

-

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

- Copyright: © 2024 by the author(s). Published by Maximum Academic Press on behalf of Nanjing Agricultural University. This article is an open access article distributed under Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

-

About this article

Cite this article

Wu M, He H. 2024. Recent advances on surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy in safety assessment and quality control of meat and meat products. Food Materials Research 4: e029 doi: 10.48130/fmr-0024-0018

Recent advances on surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy in safety assessment and quality control of meat and meat products

- Received: 10 July 2024

- Revised: 16 August 2024

- Accepted: 30 August 2024

- Published online: 11 November 2024

Abstract: With the continuous development of spectroscopy technology, surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) has been widely used as a fast and sensitive analysis method for the qualitative and quantitative analysis of trace analytes in foods. At present, SERS has been widely used in various fields such as food safety, materials, and biomedicine. However, the advances of SERS in meat safety and quality detection have not been summarized. In this review, the development history and detection principles of SERS are introduced and the advantages and potential of SERS application in the field of meat safety and quality detection evaluated. Then, two classical SERS detection modes were compared, namely labeled detection and label-free detection, in terms of the advantages, disadvantages, and application scopes. Furthermore, the specific applications of SERS in detecting bacteria, viruses, veterinary drug residues, food additives, illegal additives, and biotoxins in meat and meat products were presented. In addition, the development of SERS in meat adulteration and freshness identification are summarized. The prospects of the future development of SERS in meat safety and quality assessment will likely involve multiple method integrations, new material development, and artificial intelligence. It is expected that this review will not only provide a comprehensive summary and exploration of SERS in meat safety and quality assessment but also shed light on the future innovation and continued development of SERS in the food and meat industry.